Mato Grammar Sketch

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Exploring Material Culture Distributions in the Upper Sepik and Central New Guinea

Gender, mobility and population history: exploring material culture distributions in the Upper Sepik and Central New Guinea by Andrew Fyfe, BA (Hons) Thesis submitted for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Discipline of Geographical and Environmental Studies The University of Adelaide November 2008 …..These practices, then, and others which I will speak of later, were borrowed by the Greeks from Egypt. This is not the case, however, with the Greek custom of making images of Hermes with the phallus erect; it was the Athenians who took this from the Pelasgians, and from the Athenians the custom spread to the rest of Greece. For just at the time when the Athenians were assuming Hellenic nationality, the Pelasgians joined them, and thus first came to be regarded as Greeks. Anyone will know what I mean if he is familiar with the mysteries of the Cabiri-rites which the men of Samothrace learned from the Pelasgians, who lived in that island before they moved to Attica, and communicated the mysteries to the Athenians. This will show that the Athenians were the first Greeks to make statues of Hermes with the erect phallus, and that they learned the practice from the Pelasgians…… Herodotus c.430 BC ii Table of contents Acknowledgements vii List of figures viii List of tables xi List of Appendices xii Abstract xiv Declaration xvi Section One 1. Introduction 2 1.1 The Upper Sepik-Central New Guinea Project 2 1.2 Lapita and the exploration of relationships between language and culture in Melanesia 3 1.3 The quantification of relationships between material culture and language on New Guinea’s north coast 6 1.4 Thesis objectives 9 2. -

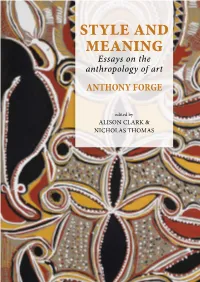

Style and Meaning Anthropology’S Engagement with Art Has a Complex and Uneven History

NICHOLAS THOMAS THOMAS NICHOLAS & CLARK ALISON style and meaning Anthropology’s engagement with art has a complex and uneven history. While style and material culture, ‘decorative art’, and art styles were of major significance for ( founding figures such as Alfred Haddon and Franz Boas, art became marginal as the EDS meaning discipline turned towards social analysis in the 1920s. This book addresses a major ) moment of renewal in the anthropology of art in the 1960s and 1970s. British Essays on the anthropologist Anthony Forge (1929-1991), trained in Cambridge, undertook fieldwork among the Abelam of Papua New Guinea in the late 1950s and 1960s, anthropology of art and wrote influentially, especially about issues of style and meaning in art. His powerful, question-raising arguments addressed basic issues, asking why so much art was produced in some regions, and why was it so socially important? style ANTHONY FORGE meaning Fifty years later, art has renewed global significance, and anthropologists are again considering both its local expressions among Indigenous peoples and its new global circulation. In this context, Forge’s arguments have renewed relevance: they help and edited by scholars and students understand the genealogies of current debates, and remind us of fundamental questions that remain unanswered. ALISON CLARK & NICHOLAS THOMAS This volume brings together Forge’s most important writings on the anthropology anthropology of art Essays on the of art, published over a thirty year period, together with six assessments of his legacy, including extended reappraisals of Sepik ethnography, by distinguished anthropologists from Australia, Germany, Switzerland and the United Kingdom Anthony Forge was born in London in 1929. -

The Lexicon of Proto Oceanic the Culture and Environment of Ancestral Oceanic Society

The lexicon of Proto Oceanic The culture and environment of ancestral Oceanic society 2 The physical environment Pacific Linguistics 545 Pacific Linguistics is a publisher specialising in grammars and linguistic descriptions, dictionaries and other materials on languages of the Pacific, Taiwan, the Philippines, Indonesia, East Timor, southeast and south Asia, and Australia. Pacific Linguistics, established in 1963 through an initial grant from the Hunter Douglas Fund, is associated with the Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies at The Australian National University. The authors and editors of Pacific Linguistics publications are drawn from a wide range of institutions around the world. Publications are refereed by scholars with relevant expertise, who are usually not members of the editorial board. FOUNDING EDITOR: Stephen A. Wurm EDITORIAL BOARD: John Bowden, Malcolm Ross and Darrell Tryon (Managing Editors), I Wayan Arka, David Nash, Andrew Pawley, Paul Sidwell, Jane Simpson EDITORIAL ADVISORY BOARD: Karen Adams, Arizona State University Lillian Huang, National Taiwan Normal Alexander Adelaar, University of Melbourne University Peter Austin, School of Oriental and African Bambang Kaswanti Purwo, Universitas Atma Studies Jaya Byron Bender, University of Hawai‘i Marian Klamer, Universiteit Leiden Walter Bisang, Johannes Gutenberg- Harold Koch, The Australian National Universität Mainz University Robert Blust, University of Hawai‘i Frantisek Lichtenberk, University of David Bradley, La Trobe University Auckland Lyle Campbell, University of Utah John Lynch, University of the South Pacific James Collins, Universiti Kebangsaan Patrick McConvell, Australian Institute of Malaysia Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Bernard Comrie, Max Planck Institute for Studies Evolutionary Anthropology William McGregor, Aarhus Universitet Soenjono Dardjowidjojo, Universitas Atma Ulrike Mosel, Christian-Albrechts- Jaya Universität zu Kiel Matthew Dryer, State University of New York Claire Moyse-Faurie, Centre National de la at Buffalo Recherche Scientifique Jerold A. -

LLO Vol.5 2013

SIL and its contribution to Oceanic linguistics1 René van den Berg SIL International Abstract:53? %/3/ %%%5%%%/ /?/%%5 paper also discusses avenues for future research and collaboration between SIL and Key words: SIL, Oceanic linguistics, collaboration Fifty years ago Arthur Capell’s article ‘Oceanic Linguistics today’ was published (Capell '*+-//3/[5 article is still worth reading, if only to get an idea of the progress made in the intervening /%678 his article by stressing the need for recording undescribed languages, collecting vernacular oral literature, doing ‘deep analysis’ of phonemic and morphological structures, as well %/3% In many respects – and this is somewhat sobering – those needs have not much changed %/ the number of languages in the Pacific is much bigger than previously estimated, while the task of describing a single language has been expanded with the need to include full In this article I discuss and evaluate the contribution of SIL to Oceanic linguistics %;;</= >?>% means presenting a personal perspective, I have tried to be objective and have taken into 3%5 /%[5[ René van den Berg //-@/ the question: to what extent has the descriptive work of SIL been informed by the various linguistic layers of linguistic research (description, documentation, typology, formal theory)? Also, to what extent can the work of SIL be expected to integrate with the work %D;E5 /=+ /J3% Although most linguists working in Oceanic languages have heard about SIL or have /3//% 3 /[/ % ・ International: members come from a variety -

Online Appendix To

Online Appendix to Hammarström, Harald & Sebastian Nordhoff. (2012) The languages of Melanesia: Quantifying the level of coverage. In Nicholas Evans & Marian Klamer (eds.), Melanesian Languages on the Edge of Asia: Challenges for the 21st Century (Language Documentation & Conservation Special Publication 5), 13-34. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. ’Are’are [alu] < Austronesian, Nuclear Austronesian, Malayo- Polynesian, Central-Eastern Malayo-Polynesian, Eastern Malayo- Polynesian, Oceanic, Southeast Solomonic, Longgu-Malaita- Makira, Malaita-Makira, Malaita, Southern Malaita Geerts, P. 1970. ’Are’are dictionary (Pacific Linguistics: Series C 14). Canberra: The Australian National University [dictionary 185 pp.] Ivens, W. G. 1931b. A Vocabulary of the Language of Marau Sound, Guadalcanal, Solomon Islands. Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies VI. 963–1002 [grammar sketch] Tryon, Darrell T. & B. D. Hackman. 1983. Solomon Islands Languages: An Internal Classification (Pacific Linguistics: Series C 72). Canberra: Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies, Australian National University. Bibliography: p. 483-490 [overview, comparative, wordlist viii+490 pp.] ’Auhelawa [kud] < Austronesian, Nuclear Austronesian, Malayo- Polynesian, Central-Eastern Malayo-Polynesian, Eastern Malayo- Polynesian, Oceanic, Western Oceanic linkage, Papuan Tip linkage, Nuclear Papuan Tip linkage, Suauic unknown, A. (2004 [1983?]). Organised phonology data: Auhelawa language [kud] milne bay province http://www.sil.org/pacific/png/abstract.asp?id=49613 1 Lithgow, David. 1987. Language change and relationships in Tubetube and adjacent languages. In Donald C. Laycock & Werner Winter (eds.), A world of language: Papers presented to Professor S. A. Wurm on his 65th birthday (Pacific Linguistics: Series C 100), 393-410. Canberra: Research School of Pacific and Asian Studies, Australian National University [overview, comparative, wordlist] Lithgow, David. -

Kwomtari Phonology and Grammar Essentials

Data Papers on Papua New Guinea Languages Volume 55 Kwomtari Phonology and Grammar Essentials edited by Murray Honsberger Carol Honsberger Ian Tupper 2008 SIL-PNG Academic Publications Ukarumpa, Papua New Guinea Papers in the series Data Papers on Papua New Guinea Languages express the authors’ knowledge at the time of writing. They normally do not provide a comprehensive treatment of the topic and may contain analyses which will be modified at a later stage. However, given the large number of undescribed languages in Papua New Guinea, SIL- PNG feels that it is appropriate to make these research results available at this time. René van den Berg, Series Editor Copyright © 2008 SIL-PNG Papua New Guinea [email protected] Published 2008 Printed by SIL Printing Press Ukarumpa, Eastern Highlands Province Papua New Guinea ISBN 9980-0-3426-0 Table of Contents List of maps and tables...................................................................................viii Abbreviations.................................................................................................... ix Introduction to the Kwomtari people and language by Carol Honsberger, Murray Honsberger and Ian Tupper ............. 1 1. Introduction................................................................................................ 2 1.1 Language setting.................................................................................. 2 1.2 The Kwomtari people........................................................................... 5 1.2.1 Traditional way of life -

Language Area Madang Province, Papua New Guinea

DigitalResources Electronic Survey Report 2011-049 ® A Sociolinguistic Survey of the Malalamai [mmt] Language Area Madang Province, Papua New Guinea John Carter Katie Carter John Grummitt Bonnie MacKenzie Janell Masters A Sociolinguistic Survey of the Malalamai [mmt] Language Area Madang Province, Papua New Guinea John Carter, Katie Carter, John Grummitt, Bonnie MacKenzie, and Janell Masters SIL International ® 2011 SIL Electronic Survey Report 2011-049, December 2011 Copyright © 2011 John Carter, Katie Carter, John Grummitt, Bonnie MacKenzie, Janell Masters, and SIL International ® All rights reserved Abstract This survey investigates vitality and language and dialect boundaries of the Malalamai [mmt] language on the eastern coast of Madang Province, Papua New Guinea (PNG). This was one of the few Austronesian languages that had not been surveyed in this area. The survey team used wordlists, observation, interviews and participatory methods in the villages of Malalamai, Bonga and Yara. Pre-existing wordlists from nearby or related Austronesian languages were compared to those elicited during the survey to calculate lexical similarities between them and the language surveyed. Linguistically, there was virtually no difference between the villages surveyed, and comparison with other languages in the area shows that the Malalamai language is distinct. In addition, reported data indicate that Malalamai is limited to only the villages surveyed. This survey report concludes that although continued and increasing use of Tok Pisin could influence -

The Bragge Collection

1 Bragge Material Culture Collection The Bragge Collection - Material Culture The material artefacts from this collection are curated by the Discipline of Anthropology, Material Culture Collection (College of Arts, Society and Education), and housed in The Cairns Institute. To enquire about these items, please contact Professor Rosita Henry. ([email protected]) Accession Name of Object Primary Description Old Dimensions Cultural Cultural Provenance Shelf Contextual Notes No Object Type Classification Registration Category Group Locality Location Number 2018.02.001.a Finial Artefact Architectual Carved wooden finial from Haus 1.a L2130 x W300 Melanesian Kanganaman Middle Sepik FS.2 The Worimbi haus tambaran was declared to be a element Tambaran (traditional ancestral x D270mm Village Province, Papua national monument under the 'National Cultural worship house) at Worimbi (aka New Guinea Property. (Preservation) Act 1965'. This Worimbi Warimbi) in Kanganaman Village, was severely damaged in an earthquake and Latmul area, Middle Sepik Province, inspected in 1980 by Soroi Marepo Eoe (b.1954) Papua New Guinea. Represents a the Assistant Curator Anthropology (1979-1983), young woman. Purchased by Laurie National Museum Papua New Guinea. The finials Bragge from Elders of Kanganaman were undamaged and saved by village Elders and Village. See full crocodile story and offered for sale with a export permit issued. The notes. Elders stated that it is 'important that the old [finials] replaced item then be removed from the area, as for old and new to be together creates spiritual conflict similar to when a man tried to bring a second wife into his home'. The finial figures represent a story of a young woman and an old woman who was known as the jealous axe. -

Language & Linguistics in Melanesia Vol. 32 No. 2, 2014 ISSN

Language & Linguistics in Melanesia Vol. 32 No. 2, 2014 ISSN: 0023-1959 Annual meeting of the Papua New Guinea Linguistic Society 'Celebrating Tok Pisin and Tok Ples', Madang, 17-19 September 2014 Living in many languages: linguistic diversity and multilingualism in Papua New Guinea Alexandra Y. Aikhenvald Language and Culture Research Centre, James Cook University Australia 1 Papua New Guinea: the land of linguistic diversity 'Why was Babel transferred to Papua New Guinea?' a missionary 'cried in exasperation' (Frerichs and Frerichs 1969: 85). This sums up the reality of PNG: it is indeed one of the most linguistically diverse spots on earth. The state of Papua New Guinea features over 830 languages. Just about over two hundred languages belong to the Austronesian languages (one of the largest in the world). The number of non-Austronesian languages — known as 'Papuan' exceeds 600. Only about twenty percent of the population speak Austronesian languages. The term 'Papuan' is a short cut: it subsumes more than sixty language families which are not demonstrably related, and a fair number of isolates (not related to anything else). The approximate numbers of languages and their speakers are given in Table 1. The only language spoken by over 100,000 people is Enga (Engan family, EHP). 1 Table 1. The languages of Papua New Guinea and approximate numbers of speakers Number of speakers Austronesian Non-Austronesian over 10,000 -100,000 about 12 about 60 1,000 -10,000 about 100 about 230 over 500 - under 1000 about 30 100 and more between 100 - 500 under 50 170 and more fewer than 100 about 10 about 50 The linguistic tapestry of PNG is made even more complex by people knowing and using several languages. -

Abau Grammar

Data Papers on Papua New Guinea Languages Volume 57 Abau Grammar Arnold (Arjen) Hugo Lock 2011 SIL-PNG Academic Publications Ukarumpa, Papua New Guinea Papers in the series Data Papers on Papua New Guinea Languages express the authors’ knowledge at the time of writing. They normally do not provide a comprehensive treatment of the topic and may contain analyses which will be modified at a later stage. However, given the large number of undescribed languages in Papua New Guinea, SIL-PNG feels that it is appropriate to make these research results available at this time. René van den Berg, Series Editor Copyright © 2011 SIL-PNG Papua New Guinea [email protected] Published 2011 Printed by SIL Printing Press Ukarumpa, Eastern Highlands Province Papua New Guinea ISBN 9980 0 3614 1 Table of Contents List of maps and tables .......................................................................... ix Abbreviations ........................................................................................ xi 1. Introduction .................................................................................... 1 1.1 Location and population .......................................................... 1 1.2 Language name ....................................................................... 2 1.3 Affiliation and earlier studies................................................... 2 1.4 Dialects ................................................................................... 3 1.5 Language use and bilingualism ............................................... -

Nukna Grammar Sketch

Data Papers on Papua New Guinea Languages Volume 61 Nukna Grammar Sketch Matthew A. Taylor 2015 SIL-PNG Academic Publications Ukarumpa, Papua New Guinea Papers in the series Data Papers on Papua New Guinea Languages express the authors’ knowledge at the time of writing. They normally do not provide a comprehensive treatment of the topic and may contain analyses which will be modified at a later stage. However, given the large number of undescribed languages in Papua New Guinea, SIL-PNG feels that it is appropriate to make these research results available at this time. René van den Berg, Series Editor Copyright © 2015 SIL-PNG Papua New Guinea [email protected] Published 2015 Printed by SIL Printing Press Ukarumpa, Eastern Highlands Province Papua New Guinea ISBN 9980 0 3990 6 Table of Contents List of maps and tables .............................................................................ix Abbreviations .......................................................................................... xii Acknowledge ments ................................................................................ xiii 1. Introduction.........................................................................................1 1.1 Location and population ................................................................. 1 1.2 Language name.............................................................................. 2 1.3 Classification and earlier studies ..................................................... 2 1.4 Dialects ........................................................................................ -

![1 Bibliography 1. H., C. Derde Orde Zusters Aan De Wisselmeren. Sint Antonius. 1952; 54: 174-175. Note: [Mission: Enarotali]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7008/1-bibliography-1-h-c-derde-orde-zusters-aan-de-wisselmeren-sint-antonius-1952-54-174-175-note-mission-enarotali-12087008.webp)

1 Bibliography 1. H., C. Derde Orde Zusters Aan De Wisselmeren. Sint Antonius. 1952; 54: 174-175. Note: [Mission: Enarotali]

1 Bibliography 1. H., C. Derde Orde Zusters aan de Wisselmeren. Sint Antonius. 1952; 54: 174-175. Note: [mission: Enarotali]. 2. H., K. G. [Holzknecht, K. ]. The Exploration of the Markham Valley: A Sidelight. Journal of the Morobe District Historical Society. 1974; 2(2): 25. Note: [mission explor 1907: Waridzian]. 3. H., S. C. Language as Key to New Guinea People: Noted Scientist's Theory. Pacific Islands Monthly. 1936; 7(4): 74-75. Note: [Kirschbaum: Ramu, general PNG]. 4. Haaft, D. A. ten. De betekenis van de "Manseren"-beweging van 1940 voor het Zendingswerk op de Noordkust van Nieuw-Guinea. De Heerbaan. 1948; 1: 71-81. Note: [mission: Biak]. 5. Haaft, D. A. ten. Onderwijs en opleiding. In: Kamma, F. C. Kruis en korwar: Een honderdjarig vraagstuk op Nieuw Guinea. Den Haag: J.N. Voorhoeve; 1953: 220-225. Note: [mission: northwest NNG]. 6. Haak, C. J. Kerkelijk onderwijs. In: Vries, Tj. S. de, Editor. Eenopen plek in het oerwoud: Evangelieverkondiging aan het volk van Irian Jaya. Groningen: Uitgeverij De Vyurbaak b.v.; 1983: 125-139. Note: [mission: Bomakia]. 7. Haak, C. J.; Zandbergen, D. J. ... Ik heb u een voorbeeld gegeven. In: Vries, Tj. S. de, Editor. Eenopen plek in het oerwoud: Evangelieverkondiging aan het volk van Irian Jaya. Groningen: Uitgeverij De Vyurbaak b.v.; 1983: 151-160. Note: [mission: Kawagit]. 8. Haan, J. H. de. Streekplanontwikkeling in Nederlands-Nieuw- Guinea, in het bijzonder in het Ajamaroegebied. Nieuw-Guinea Studiën. 1958; 2: 121-148, 169-205. Note: [Ajamaru]. 9. Haan, R. den. Het Varkensfeest zoals het plaatsvindt in het gebied van de rivieren Kao, Muju en Mandobo (Ned.