National Perspective-Round Table I

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Contents SEAGULL Theatre QUARTERLY

S T Q Contents SEAGULL THeatRE QUARTERLY Issue 17 March 1998 2 EDITORIAL Editor 3 Anjum Katyal ‘UNPEELING THE LAYERS WITHIN YOURSELF ’ Editorial Consultant Neelam Man Singh Chowdhry Samik Bandyopadhyay 22 Project Co-ordinator A GATKA WORKSHOP : A PARTICIPANT ’S REPORT Paramita Banerjee Ramanjit Kaur Design 32 Naveen Kishore THE MYTH BEYOND REALITY : THE THEATRE OF NEELAM MAN SINGH CHOWDHRY Smita Nirula 34 THE NAQQALS : A NOTE 36 ‘THE PERFORMING ARTIST BELONGED TO THE COMMUNITY RATHER THAN THE RELIGION ’ Neelam Man Singh Chowdhry on the Naqqals 45 ‘YOU HAVE TO CHANGE WITH THE CHANGING WORLD ’ The Naqqals of Punjab 58 REVIVING BHADRAK ’S MOGAL TAMSA Sachidananda and Sanatan Mohanty 63 AALKAAP : A POPULAR RURAL PERFORMANCE FORM Arup Biswas Acknowledgements We thank all contributors and interviewees for their photographs. 71 Where not otherwise credited, A DIALOGUE WITH ENGLAND photographs of Neelam Man Singh An interview with Jatinder Verma Chowdhry, The Company and the Naqqals are by Naveen Kishore. 81 THE CHALLENGE OF BINGLISH : ANALYSING Published by Naveen Kishore for MULTICULTURAL PRODUCTIONS The Seagull Foundation for the Arts, Jatinder Verma 26 Circus Avenue, Calcutta 700017 86 MEETING GHOSTS IN ORISSA DOWN GOAN ROADS Printed at Vinayaka Naik Laurens & Co 9 Crooked Lane, Calcutta 700 069 S T Q SEAGULL THeatRE QUARTERLY Dear friend, Four years ago, we started a theatre journal. It was an experiment. Lots of questions. Would a journal in English work? Who would our readers be? What kind of material would they want?Was there enough interesting and diverse work being done in theatre to sustain a journal, to feed it on an ongoing basis with enough material? Who would write for the journal? How would we collect material that suited the indepth attention we wanted to give the subjects we covered? Alongside the questions were some convictions. -

Of Contemporary India

OF CONTEMPORARY INDIA Catalogue Of The Papers of Prabhakar Machwe Plot # 2, Rajiv Gandhi Education City, P.O. Rai, Sonepat – 131029, Haryana (India) Dr. Prabhakar Machwe (1917-1991) Prolific writer, linguist and an authority on Indian literature, Dr. Prabhakar Machwe was born on 26 December 1917 at Gwalior, Madhya Pradesh, India. He graduated from Vikram University, Ujjain and obtained Masters in Philosophy, 1937, and English Literature, 1945, Agra University; Sahitya Ratna and Ph.D, Agra University, 1957. Dr. Machwe started his career as a lecturer in Madhav College, Ujjain, 1938-48. He worked as Literary Producer, All India Radio, Nagpur, Allahabad and New Delhi, 1948-54. He was closely associated with Sahitya Akademi from its inception in 1954 and served as Assistant Secretary, 1954-70, and Secretary, 1970-75. Dr. Machwe was Visiting Professor in Indian Studies Departments at the University of Wisconsin and the University of California on a Fulbright and Rockefeller grant (1959-1961); and later Officer on Special Duty (Language) in Union Public Service Commission, 1964-66. After retiring from Sahitya Akademi in 1975, Dr. Machwe was a visiting fellow at the Institute of Advanced Studies, Simla, 1976-77, and Director of Bharatiya Bhasha Parishad, Calcutta, 1979-85. He spent the last years of his life in Indore as Chief Editor of a Hindi daily, Choutha Sansar, 1988-91. Dr. Prabhakar Machwe travelled widely for lecture tours to Germany, Russia, Sri Lanka, Mauritius, Japan and Thailand. He organised national and international seminars on the occasion of the birth centenaries of Mahatma Gandhi, Rabindranath Tagore, and Sri Aurobindo between 1961 and 1972. -

The Inventory of the Richard Roud Collection #1117

The Inventory of the Richard Roud Collection #1117 Howard Gotlieb Archival Research Center ROOD, RICHARD #1117 September 1989 - June 1997 Biography: Richard Roud ( 1929-1989), as director of both the New York and London Film Festivals, was responsible for both discovering and introducing to a wider audience many of the important directors of the latter half th of the 20 - century (many of whom he knew personally) including Bernardo Bertolucci, Robert Bresson, Luis Buiiuel, R.W. Fassbinder, Jean-Luc Godard, Werner Herzog, Terry Malick, Ermanno Ohni, Jacques Rivette and Martin Scorsese. He was an author of books on Jean-Marie Straub, Jean-Luc Godard, Max Ophuls, and Henri Langlois, as well as the editor of CINEMA: A CRITICAL DICTIONARY. In addition, Mr. Roud wrote extensive criticism on film, the theater and other visual arts for The Manchester Guardian and Sight and Sound and was an occasional contributor to many other publications. At his death he was working on an authorized biography of Fran9ois Truffaut and a book on New Wave film. Richard Roud was a Fulbright recipient and a Chevalier in the Legion of Honor. Scope and contents: The Roud Collection (9 Paige boxes, 2 Manuscript boxes and 3 Packages) consists primarily of book research, articles by RR and printed matter related to the New York Film Festival and prominent directors. Material on Jean-Luc Godard, Francois Truffaut and Henri Langlois is particularly extensive. Though considerably smaller, the Correspondence file contains personal letters from many important directors (see List ofNotable Correspondents). The Photographs file contains an eclectic group of movie stills. -

S Play: Bhanga Bhanga Chhobi

Girish Karnad’s Play: Bhanga Bhanga Chhobi Playwright: Girish Karnad Translator: Srotoswini Dey Director: Tulika Das Group: Kolkata Bohuswar, Kolkata Language: Bengali Duration: 1 hr 10 mins The Play The play opens with Manjula Ray in a television studio, giving one of her countless interviews. Manjula is a successful Bengali writer whose first novel in English has got favourable reviews from the West. She talks about her life and her darling husband Pramod, and fondly reminisces about Malini, her wheel-chair bound sister. After the interview, Manjula is ready to leave the studio but is confronted by an image. Gradually Manjula starts unfolding her life showing two facets of the same character. The conversations between the character on stage and the chhaya-murti go on and Manjula peels layer after layer, revealing raw emotions and complexities of the relationship between Manjula, Promod and Malini. We can relate to both Manjula and Malini… all of us being flawed in some way or the other, and that’s what makes us human. Director’s Note I wanted to explore the text of Girish Karnad’s Broken Images with my own understanding of Manjula, the lady portraying two facets of the same character. Despite all her shortcomings and flaws, she did not degenerate into a stereotypical vamp. Although she had made unforgivable mistakes, wasn’t there enough reason for her to exercise duplicity and betrayal? I found myself asking this question and wanting to see the larger picture through another prism. It has taken years for the Bengali stage to come up with an adaptation of the 2004 play. -

New and Bestselling Titles Sociology 2016-2017

New and Bestselling titles Sociology 2016-2017 www.sagepub.in Sociology | 2016-17 Seconds with Alice W Clark How is this book helpful for young women of Any memorable experience that you hadhadw whilehile rural areas with career aspirations? writing this book? Many rural families are now keeping their girls Becoming part of the Women’s Studies program in school longer, and this book encourages at Allahabad University; sharing in the colourful page 27A these families to see real benefit for themselves student and faculty life of SNDT University in supporting career development for their in Mumbai; living in Vadodara again after daughters. It contributes in this way by many years, enjoying friends and colleagues; identifying the individual roles that can be played reconnecting with friendships made in by supportive fathers and mothers, even those Bangalore. Being given entrée to lively students with very little education themselves. by professors who cared greatly about them. Being treated wonderfully by my interviewees. What facets of this book bring-in international Any particular advice that you would like to readership? share with young women aiming for a successful Views of women’s striving for self-identity career? through professionalism; the factors motivating For women not yet in college: Find supporters and encouraging them or setting barriers to their in your family to help argue your case to those accomplishments. who aren’t so supportive. Often it’s submissive Upward trends in women’s education, the and dutiful mothers who need a prompt from narrowing of the gender gap, and the effects a relative with a broader viewpoint. -

Sls Vkosnu I=Kasa Ftuesa Iathdj.K Dh ,D Gh La[;K Vusd Ckj Eqnz.K

CORRECTED SR No. FORM NO APPLICANT NAME FATHER/HUSBAND NAME FORM NO LATE VIJAY KUMAR 1 8152 8152 KOMAL KASHYAP KASHYAP 2 8152 8152-A ROHIT KUMAR RAM KUMAR 3 8206 8206 ARTI VERMA LATE ASHOK KUMAR VERMA 4 8206 8206-A SAJJAN KUMAR MISHRA GANGA RAM MISHRA 5 8224 8224 DHANANJAY HRIDAY NARAYAN 6 8224 8224-A MEENA DIXIT BAMB BAHADUR TIWARI 7 8364 8364 KANCHAN VERMA RAJKUMAR VERMA 8 8364 8364-A HARI SHANKAR GAUTAM BHGEDU DAS GAUTAM 9 8369 8369 Om prakash KADILE 10 8369 8369-A OM PRAKASH, PATHAK RAM DHEERAJ PATHAK 11 8824 8824 ROLI YADAV SUJIT KUMAR YADAV 12 8824 8824-A DHARMENDRA SINGH LATE SHYAM BIHARI SINGH 13 9120 9120 JAGNATH GUPTA LATE RAM DATT PRASAD 14 9120 9120-A MANEESH KUMAR SATGURU SARAN 15 9215 9215 SANTOSH KUMARI BABULAL TIWARI 16 9215 9215-A NEERAJ MISHRA DAYA SHANKAR MISHRA 17 9215 9215-B SUNITA VERMA LAKHAN VERMA 18 9215 9215-C INDRESH RAM PALTAN 19 9215 9215-D MOLI DEVI MAURYA SW. VIJAY MAURYA 20 9215 9215-E MITHILESH MAHTO RAGHUVEER MAHTO 21 9215 9215-F MANJU DEVI JAWAHAR BHAGAT 22 9215 9215-G BINDESHWARI RAM RATAN 23 9215 9215-H ANITA VERMA SAURABH VERMA Page 1 of 31 CORRECTED SR No. FORM NO APPLICANT NAME FATHER/HUSBAND NAME FORM NO 24 9215 9215-I RANI KASHYAP MOHAN LAL 25 9215 9215-J GEETA VISRAM 26 9215 9215-K NEELAM DEVI VISHNU DEV PRASAD 27 9215 9215-L NAGARAJ JAISWAL LT. LALTA PRASAD RAJ 28 9235 9235 AKHILESH KUMAR THARU RAJENDRA KUMAR 29 9235 9235-A SAVITA SATISH GUPTA 30 10176 10176 MOHD RAJU SHAMSHER 31 10176 10176-A SHIVAM DHUNNU 32 10333 10333 SHASHI SINGH DEVESH KUMAR SINGH 33 10333 10333-A PRIYANKA TIWARI DHIRENDRA KUMAR TIWAR 34 10343 10343 MANJU TRIPATHI JAY PRAKASH TRIPATHI 35 10343 10343-A RAVI RAM CHANDER NIGAM 36 10453 10453 KHUSHABU NISHA MO. -

Journalism Is the Craft of Conveying News, Descriptive Material and Comment Via a Widening Spectrum of Media

Journalism is the craft of conveying news, descriptive material and comment via a widening spectrum of media. These include newspapers, magazines, radio and television, the internet and even, more recently, the cellphone. Journalists—be they writers, editors or photographers; broadcast presenters or producers—serve as the chief purveyors of information and opinion in contemporary mass society According to BBC journalist, Andrew Marr, "News is what the consensus of journalists determines it to be." From informal beginnings in the Europe of the 18th century, stimulated by the arrival of mechanized printing—in due course by mass production and in the 20th century by electronic communications technology— today's engines of journalistic enterprise include large corporations with global reach. The formal status of journalism has varied historically and, still varies vastly, from country to country. The modern state and hierarchical power structures in general have tended to see the unrestricted flow of information as a potential threat, and inimical to their own proper function. Hitler described the Press as a "machine for mass instruction," ideally, a "kind of school for adults." Journalism at its most vigorous, by contrast, tends to be propelled by the implications at least of the attitude epitomized by the Australian journalist John Pilger: "Secretive power loathes journalists who do their job, who push back screens, peer behind façades, lift rocks. Opprobrium from on high is their badge of honour." New journalism New Journalism was the name given to a style of 1960s and 1970s news writing and journalism which used literary techniques deemed unconventional at the time. The term was codified with its current meaning by Tom Wolfe in a 1973 collection of journalism articles. -

Hindi Theater Is Not Seen in Any Other Theatre

NATYA SHODH SANSTHAN DISCUSSION ON HINDI THEATRE FROM THE COLLECTIONS OF NATYA SHODH SANSTHAN AUDIO LIBRARY THE PRESENT SCENARIO OF HINDI THEATRE IN CALCUTTA ON th 15 May 1983 AT NATYA SHODH SANSTHAN PARTICIPANTS PRATIBHA AGRAWAL, SAMIK BANDYOPADHYAY, SHIV KUMAR JOSHI, SHYAMANAND JALAN, MANAMOHON THAKORE SHEO KUMAR JHUNJHUNWALA, SWRAN CHOWDHURY, TAPAS SEN, BIMAL LATH, GAYANWATI LATH, SURESH DUTT, PRAMOD SHROFF NATYA SHODH SANSTHAN EE 8, SECTOR 2, SALT LAKE, KOLKATA 91 MAIL : [email protected] Phone (033)23217667 1 NATYA SHODH SANSTHAN Pratibha Agrawal We are recording the discussion on “The present scenario of the Hindi Theatre in Calcutta”. The participants include – Kishen Kumar, Shymanand Jalan, Shiv Kumar Joshi, Shiv Kumar Jhunjhunwala, Manamohan Thakore1, Samik Banerjee, Dharani Ghosh, Usha Ganguly2 and Bimal Lath. We welcome all of you on behalf of Natya Shodh Sansthan. For quite some time we, the actors, directors, critics and the members of the audience have been appreciating and at the same time complaining about the plays that are being staged in Calcutta in the languages that are being practiced in Calcutta, be it in Hindi, English, Bangla or any other language. We felt that if we, the practitioners should sit down and talk about the various issues that are bothering us, we may be able to solve some of the problems and several issues may be resolved. Often it so happens that the artists take one side and the critics-audience occupies the other. There is a clear division – one group which creates and the other who criticizes. Many a time this proves to be useful and necessary as well. -

List of Empanelled Artist

INDIAN COUNCIL FOR CULTURAL RELATIONS EMPANELMENT ARTISTS S.No. Name of Artist/Group State Date of Genre Contact Details Year of Current Last Cooling off Social Media Presence Birth Empanelment Category/ Sponsorsred Over Level by ICCR Yes/No 1 Ananda Shankar Jayant Telangana 27-09-1961 Bharatanatyam Tel: +91-40-23548384 2007 Outstanding Yes https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vwH8YJH4iVY Cell: +91-9848016039 September 2004- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Vrts4yX0NOQ [email protected] San Jose, Panama, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YDwKHb4F4tk [email protected] Tegucigalpa, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SIh4lOqFa7o Guatemala City, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MiOhl5brqYc Quito & Argentina https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=COv7medCkW8 2 Bali Vyjayantimala Tamilnadu 13-08-1936 Bharatanatyam Tel: +91-44-24993433 Outstanding No Yes https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wbT7vkbpkx4 +91-44-24992667 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zKvILzX5mX4 [email protected] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kyQAisJKlVs https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=q6S7GLiZtYQ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WBPKiWdEtHI 3 Sucheta Bhide Maharashtra 06-12-1948 Bharatanatyam Cell: +91-8605953615 Outstanding 24 June – 18 July, Yes https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WTj_D-q-oGM suchetachapekar@hotmail 2015 Brazil (TG) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UOhzx_npilY .com https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SgXsRIOFIQ0 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lSepFLNVelI 4 C.V.Chandershekar Tamilnadu 12-05-1935 Bharatanatyam Tel: +91-44- 24522797 1998 Outstanding 13 – 17 July 2017- No https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ec4OrzIwnWQ -

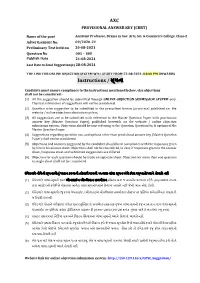

AXC Instructions / ૂચના

AXC PROVISIONAL ANSWER KEY (CBRT) Name of the post Assistant Professor, Drama in Gov. Arts, Sci. & Commerce College, Class-2 Advertisement No. 69/2020-21 Preliminary Test held on 20-08-2021 Question No 001 – 300 Publish Date 21-08-2021 Last Date to Send Suggestion(s) 28-08-2021 THE LINK FOR ONLINE OBJECTION SYSTEM WILL START FROM 22-08-2021; 04:00 PM ONWARDS Instructions / ચનાૂ Candidate must ensure compliance to the instructions mentioned below, else objections shall not be considered: - (1) All the suggestion should be submitted through ONLINE OBJECTION SUBMISSION SYSTEM only. Physical submission of suggestions will not be considered. (2) Question wise suggestion to be submitted in the prescribed format (proforma) published on the website / online objection submission system. (3) All suggestions are to be submitted with reference to the Master Question Paper with provisional answer key (Master Question Paper), published herewith on the website / online objection submission system. Objections should be sent referring to the Question, Question No. & options of the Master Question Paper. (4) Suggestions regarding question nos. and options other than provisional answer key (Master Question Paper) shall not be considered. (5) Objections and answers suggested by the candidate should be in compliance with the responses given by him in his answer sheet. Objections shall not be considered, in case, if responses given in the answer sheet /response sheet and submitted suggestions are differed. (6) Objection for each question should be made on separate sheet. Objection for more than one question in single sheet shall not be considered. ઉમેદવાર નીચેની ૂચનાઓું પાલન કરવાની તકદાર રાખવી, અયથા વાંધા- ૂચન ગે કરલ રૂઆતો યાને લેવાશે નહ (1) ઉમેદવાર વાંધાં- ૂચનો ફત ઓનલાઈન ઓશન સબમીશન સીટમ ારા જ સબમીટ કરવાના રહશે. -

Criterion an International Journal in English ISSN 0976-8165

The Criterion www.the-criterion.com An International Journal in English ISSN 0976-8165 Revitalizing the Tradition: Mahesh Dattani’s Contribution to Indian English Drama Farah Deeba Shafiq M.Phil Scholar Department of English University of Kashmir Indian drama has had a rich and ancient tradition: the natyashastra being the oldest of the texts on the theory of drama. The dramatic form in India has worked through different traditions-the epic, the folk, the mythical, the realistic etc. The experience of colonization, however, may be responsible for the discontinuation of an indigenous native Indian dramatic form.During the immediate years following independence, dramatists like Mohan Rakesh, Badal Sircar, Girish Karnad, Vijay Tendulkar, Dharamvir Bharati et al laid the foundations of an autonomous “Indian” aesthetic-a body of plays that helped shape a new “National” dramatic tradition. It goes to their credit to inaugurate an Indian dramatic tradition that interrogated the socio-political complexities of the nascent Indian nation. However, it’s pertinent to point out that these playwrights often wrote in their own regional languages like Marathi, Kannada, Bengali and Hindi and only later translated their plays into English. Indian English drama per se finds its first practitioners in Shri Aurobindo, Harindarnath Chattopadhyaya, and A.S.P Ayyar. In the post- independence era, Asif Curriumbhoy (b.1928) is a pioneer of Indian English drama with almost thirty plays in his repertoire. However, owing to the spectacular success of the Indian English novel, Drama in English remained a minor genre and did not find its true voice until the arrival of Mahesh Dattani. -

Download the Complete Issue Here

Theatre for Change 1 Editorial ‘The very process of the workshop does so much for women. The process is an end in itself. For women who are not given to articulating their views, women who are not given to exploring their bodies in a creative way, for feeling good, for feeling fresh. Just doing physical and breathing exercises is a liberating experience for them. Then sharing experiences with each other and discovering that they are not insane, you know, discovering that every woman has dissatisfaction and negative feelings, touching other lives . When you come together in a space, you develop a trust, sharing with each other, enjoying just being in this space, enjoying singing and creating, out of your own experiences, your own plays’—Tripurari Sharma Theatre as process—workshopping—is an empowering activity. It encourages self- expression, develops self-confidence and communication skills, and promotes teamwork, cooperation, sharing. It is also therapeutic, helping individuals to probe within and express—share—deeply emotional experiences. Role-playing enables one to ‘enact’ something deeply personal that one is not otherwise able to express, displacing it and rendering it ‘safe’, supposedly ‘fictionalized’. In short, workshopping can be a liberatory experience. For women who, in our society especially, are not encouraged to develop an intimacy with their bodies, who are conditioned to be ashamed or uncomfortable about their physicality, the process of focusing on the body, on exercises which change one’s awareness of and relationship with and deployment of one’s body, offers an additional benefit, opening up a dimension of physicality which is normally out of bounds.