Download the Complete Issue Here

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Of Contemporary India

OF CONTEMPORARY INDIA Catalogue Of The Papers of Prabhakar Machwe Plot # 2, Rajiv Gandhi Education City, P.O. Rai, Sonepat – 131029, Haryana (India) Dr. Prabhakar Machwe (1917-1991) Prolific writer, linguist and an authority on Indian literature, Dr. Prabhakar Machwe was born on 26 December 1917 at Gwalior, Madhya Pradesh, India. He graduated from Vikram University, Ujjain and obtained Masters in Philosophy, 1937, and English Literature, 1945, Agra University; Sahitya Ratna and Ph.D, Agra University, 1957. Dr. Machwe started his career as a lecturer in Madhav College, Ujjain, 1938-48. He worked as Literary Producer, All India Radio, Nagpur, Allahabad and New Delhi, 1948-54. He was closely associated with Sahitya Akademi from its inception in 1954 and served as Assistant Secretary, 1954-70, and Secretary, 1970-75. Dr. Machwe was Visiting Professor in Indian Studies Departments at the University of Wisconsin and the University of California on a Fulbright and Rockefeller grant (1959-1961); and later Officer on Special Duty (Language) in Union Public Service Commission, 1964-66. After retiring from Sahitya Akademi in 1975, Dr. Machwe was a visiting fellow at the Institute of Advanced Studies, Simla, 1976-77, and Director of Bharatiya Bhasha Parishad, Calcutta, 1979-85. He spent the last years of his life in Indore as Chief Editor of a Hindi daily, Choutha Sansar, 1988-91. Dr. Prabhakar Machwe travelled widely for lecture tours to Germany, Russia, Sri Lanka, Mauritius, Japan and Thailand. He organised national and international seminars on the occasion of the birth centenaries of Mahatma Gandhi, Rabindranath Tagore, and Sri Aurobindo between 1961 and 1972. -

An End to Antisemitism!

Confronting Antisemitism in Modern Media, the Legal and Political Worlds An End to Antisemitism! Edited by Armin Lange, Kerstin Mayerhofer, Dina Porat, and Lawrence H. Schiffman Volume 5 Confronting Antisemitism in Modern Media, the Legal and Political Worlds Edited by Armin Lange, Kerstin Mayerhofer, Dina Porat, and Lawrence H. Schiffman ISBN 978-3-11-058243-7 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-067196-4 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-067203-9 DOI https://10.1515/9783110671964 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. For details go to https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Library of Congress Control Number: 2021931477 Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2021 Armin Lange, Kerstin Mayerhofer, Dina Porat, Lawrence H. Schiffman, published by Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston The book is published with open access at www.degruyter.com Cover image: Illustration by Tayler Culligan (https://dribbble.com/taylerculligan). With friendly permission of Chicago Booth Review. Printing and binding: CPI books GmbH, Leck www.degruyter.com TableofContents Preface and Acknowledgements IX LisaJacobs, Armin Lange, and Kerstin Mayerhofer Confronting Antisemitism in Modern Media, the Legal and Political Worlds: Introduction 1 Confronting Antisemitism through Critical Reflection/Approaches -

Confronting Antisemitism in Modern Media, the Legal and Political Worlds an End to Antisemitism!

Confronting Antisemitism in Modern Media, the Legal and Political Worlds An End to Antisemitism! Edited by Armin Lange, Kerstin Mayerhofer, Dina Porat, and Lawrence H. Schiffman Volume 5 Confronting Antisemitism in Modern Media, the Legal and Political Worlds Edited by Armin Lange, Kerstin Mayerhofer, Dina Porat, and Lawrence H. Schiffman ISBN 978-3-11-058243-7 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-067196-4 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-067203-9 DOI https://10.1515/9783110671964 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. For details go to https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Library of Congress Control Number: 2021931477 Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available on the Internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2021 Armin Lange, Kerstin Mayerhofer, Dina Porat, Lawrence H. Schiffman, published by Walter de Gruyter GmbH, Berlin/Boston The book is published with open access at www.degruyter.com Cover image: Illustration by Tayler Culligan (https://dribbble.com/taylerculligan). With friendly permission of Chicago Booth Review. Printing and binding: CPI books GmbH, Leck www.degruyter.com TableofContents Preface and Acknowledgements IX LisaJacobs, Armin Lange, and Kerstin Mayerhofer Confronting Antisemitism in Modern Media, the Legal and Political Worlds: Introduction 1 Confronting Antisemitism through Critical Reflection/Approaches -

Group Housing

LIST OF ALLOTED PROPERTIES DEPARTMENT NAME- GROUP HOUSING S# RID PROPERTY NO. APPLICANT NAME AREA 1 60244956 29/1013 SEEMA KAPUR 2,000 2 60191186 25/K-056 CAPT VINOD KUMAR, SAROJ KUMAR 128 3 60232381 61/E-12/3008/RG DINESH KUMAR GARG & SEEMA GARG 154 4 60117917 21/B-036 SUDESH SINGH 200 5 60036547 25/G-033 SUBHASH CH CHOPRA & SHWETA CHOPRA 124 6 60234038 33/146/RV GEETA RANI & ASHOK KUMAR GARG 200 7 60006053 37/1608 ATEET IMPEX PVT. LTD. 55 8 39000209 93A/1473 ATS VI MADHU BALA 163 9 60233999 93A/01/1983/ATS NAMRATA KAPOOR 163 10 39000200 93A/0672/ATS ASHOK SOOD SOOD 0 11 39000208 93A/1453 /14/AT AMIT CHIBBA 163 12 39000218 93A/2174/ATS ARUN YADAV YADAV YADAV 163 13 39000229 93A/P-251/P2/AT MAMTA SAHNI 260 14 39000203 93A/0781/ATS SHASHANK SINGH SINGH 139 15 39000210 93A/1622/ATS RAJEEV KUMAR 0 16 39000220 93A/6-GF-2/ATS SUNEEL GALGOTIA GALGOTIA 228 17 60232078 93A/P-381/ATS PURNIMA GANDHI & MS SHAFALI GA 200 18 60233531 93A/001-262/ATS ATUULL METHA 260 19 39000207 93A/0984/ATS GR RAVINDRA KUMAR TYAGI 163 20 39000212 93A/1834/ATS GR VIJAY AGARWAL 0 21 39000213 93A/2012/1 ATS KUNWAR ADITYA PRAKASH SINGH 139 22 39000211 93A/1652/01/ATS J R MALHOTRA, MRS TEJI MALHOTRA, ADITYA 139 MALHOTRA 23 39000214 93A/2051/ATS SHASHI MADAN VARTI MADAN 139 24 39000202 93A/0761/ATS GR PAWAN JOSHI 139 25 39000223 93A/F-104/ATS RAJESH CHATURVEDI 113 26 60237850 93A/1952/03 RAJIV TOMAR 139 27 39000215 93A/2074 ATS UMA JAITLY 163 28 60237921 93A/722/01 DINESH JOSHI 139 29 60237832 93A/1762/01 SURESH RAINA & RUHI RAINA 139 30 39000217 93A/2152/ATS CHANDER KANTA -

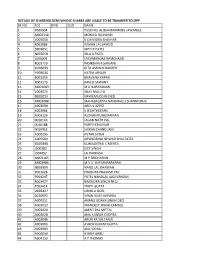

Details of Shareholders Whose Shares Are Liable to Be Transfer to Iepf Sr.No Fol Dpid Clid Name 1 Y000004 Yusufali Alibhaikarimj

DETAILS OF SHAREHOLDERS WHOSE SHARES ARE LIABLE TO BE TRANSFER TO IEPF SR.NO FOL DPID CLID NAME 1 Y000004 YUSUFALI ALIBHAIKARIMJEE JAWANJEE 2 M003118 MONICA DILAWARI 3 V003054 V CHANDRA SHEKHAR 4 K003086 KISHAN LAL JANGID 5 D003051 DIPTI P PATEL 6 N003058 NILA A PATEL 7 L003009 LACHMANDAS RAMCHAND 8 R003170 RASIKBHAI K SAVJANI 9 G003039 GITA ASHWIN BANKER 10 H003036 HATIM ARIAAR 11 B003056 BHAVANA KAPASI 12 R003173 RAVI D SAWANT 13 M003083 M A NARAYANAN 14 V003075 VIJAY MALLYA 15 N003055 NAYEEMUDDIN SYED 16 M003088 MAHABALAPPA NANDIHALLI SHANMUKHA 17 A003090 ABDUL AZEEZ 18 K003066 K JEGATHEESAN 19 A003126 ASOKAN KUNJURAMAN 20 0010146 JAGAN NATH PAL 21 0010188 PARTH KHAKHAR 22 0010953 SHIKAR CHAND JAIN 23 A000295 AVTAR SINGH 24 A005583 ARVINDBHAI ISHWAR BHAI PATEL 25 G003898 GUNVANTRAI C MEHTA 26 J000382 JEET SINGH 27 J004092 JAI PARKASH 28 M003185 M P SRIDHARAN 29 M003986 M.V.S. SURYANARAYANA 30 N003999 NAND LAL DHAWAN 31 P003628 PRADNYA PRAKASH PAI 32 P004247 PATEL NANDLAL JAGJIVANDAS 33 R003427 RAJENDRA SINGH NEGI 34 T003414 TRIPTI GUPTA 35 U003427 URMILA GOEL 36 0010970 KIRAN VIJAY JAIPURIA 37 A000311 ANANG UDAYA SINGH DEO 38 A003013 AMARJEET SINGH KAMBOJ 39 A003020 AMRIT PAL MITTAL 40 A003028 ANIL KUMAR CHOPRA 41 A003046 ARUN KR SULTANIA 42 A003066 ASHOK KUMAR GUPTA 43 A003983 ANIL GOYAL 44 A004030 A RAJA BABU 45 A004113 A T THOMAS 46 A004564 A. RAJA BABU 47 A004666 ANIL KUMAR LUKKAD 48 A004677 ASHA DEVI 49 A004915 ASHOK GUPTA 50 A005458 ANURAG JAIN 51 A005468 AGA REDDY VANTERU 52 B000031 BHAIRULAL GULABCHAND 53 B000049 BALMUKAND AGARWAL -

Book 1 Peshi Register from 01-02-2014 to 10-02-2014

PESHI REGISTER Peshi Register From 01-02-2014 To 10-02-2014 Book No. 1 No. S.No. Reg.No. IstParty IIndParty Type of Deed Address Value Stamp Book No. Paid Bara Hindu Rao 12237 -- Mohd Asif Khali Qamar SALE , SALE WITHIN MC Bara Hindu Rao , House No. 6631-32 369,500.00 22,170.00 1 AREA ,Road No. Chamelian road, Mustail No. , Khasra , Area1 11, Area2 0, Area3 0 Bara Hindu Rao Civil Line 22287 -- Ankita Goel Madhav Goel RELINQUISHMENT DEED Civil Line, House No. 3 ,Road No. 0.00 100.00 1 , RELINQUISHMENT Court Road, Mustail No. , Khasra , DEED Area1 0, Area2 0, Area3 0 Civil Line Roshanara Road 32394 -- Anil Kumar Dharmender Kumar SALE , SALE WITHIN MC Roshanara Road , House No. 8491 1,000,000.00 60,000.00 1 AREA To 8493 (new) ,Road No. Gali Abdula Beg, Mustail No. , Khasra , Area1 44, Area2 0, Area3 0 Roshanara Road Subzi Mandi 42421 -- Ashok Kumar Anand Jindal TRANSFER OF LEASE , Subzi Mandi , House No. 30 ,Road 2,830,000.00 84,900.00 1 Luthra TRANSFER OF LEASE No. Indra Mkt, Mustail No. , Khasra , Area1 22, Area2 0, Area3 0 Subzi Mandi Village Burari 5-- 901 Rakesh Kumar Jain Nem Chand Jain , RELINQUISHMENT DEED Village Burari , House No. ,Road 0.00 100.00 1 , C-64 Ph-1 Ashok C-64 Ph-1 Ashok , RELINQUISHMENT No. Extended lal Dora, Mustail No. , Vihar delhi Vihar delhi DEED Khasra 472/1, Area1 0, Area2 10, Area3 0 Village Burari Roop Nagar 6-- 902 Kashmiri Lal Sanjna , 8/5 Roop SALE , SALE WITHIN MC Roop Nagar, House No. -

UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Berkeley UC Berkeley Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Clarity, Communication, and Understandability: Theorizing Language in al-Bāqillānī’s I‘jāz al- Qurʾān and Uṣūl al-Fiqh Texts Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/3k82r14q Author Friedman, Rachel Anne Publication Date 2015 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Clarity, Communication, and Understandability: Theorizing Language in al-Bāqillānī’s Iʿjāz al-Qurʾān and Uṣūl al-Fiqh Texts By Rachel Anne Friedman A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Near Eastern Studies in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in Charge: Professor Margaret Larkin, Chair Professor Asad Ahmed Professor Chana Kronfeld Professor Niklaus Largier Summer 2015 Abstract Clarity, Communication, and Understandability: Theorizing Language in al-Bāqillānī’s I‘jāz al-Qurʾān and Uṣūl al-Fiqh Texts by Rachel Anne Friedman Doctor of Philosophy in Near Eastern Studies Professor Margaret Larkin, Chair University of California, Berkeley Abū Bakr al-Bāqillānī (d. 403 AH/1013 CE) is known as a preeminent theorist of both the Ashʿarī school of Islamic theology and the Mālikī school of law, and his writings span a wide range of disciplines. This dissertation brings together his thought in two apparently disparate discourses, uṣūl al-fiqh (jurisprudence) and iʿjāz al-Qurʾān (inimitability of the Qurʾān), to highlight how these discourses are actually in dialogue with each other. It explores the centrality of al-Bāqillānī’s theory of language in his thought and devotes particular attention to his understanding of the role of figurative language. -

Université De Montréal /7 //F Ç /1 L7iq/5-( Dancing Heroines: Sexual Respectability in the Hindi Cinema Ofthe 1990S Par Tania

/7 //f Ç /1 l7Iq/5-( Université de Montréal Dancing Heroines: Sexual Respectability in the Hindi Cinema ofthe 1990s par Tania Ahmad Département d’anthropologie Faculté des arts et sciences Mémoire présenté à la Faculté des études supérieures en vue de l’obtention du grade de M.Sc. en programme de la maîtrise août 2003 © Tania Ahrnad 2003 n q Université (1111 de Montréal Direction des bibliothèques AVIS L’auteur a autorisé l’Université de Montréal à reproduire et diffuser, en totalité ou en partie, par quelque moyen que ce soit et sur quelque support que ce soit, et exclusivement à des fins non lucratives d’enseignement et de recherche, des copies de ce mémoire ou de cette thèse. L’auteur et les coauteurs le cas échéant conservent la propriété du droit d’auteur et des droits moraux qui protègent ce document. Ni la thèse ou le mémoire, ni des extraits substantiels de ce document, ne doivent être imprimés ou autrement reproduits sans l’autorisation de l’auteur. Afin de se conformer à la Loi canadienne sur la protection des renseignements personnels, quelques formulaires secondaires, coordonnées ou signatures intégrées au texte ont pu être enlevés de ce document. Bien que cela ait pu affecter la pagination, il n’y a aucun contenu manquant. NOTICE The author of this thesis or dissertation has granted a nonexclusive license allowing Université de Montréal to reproduce and publish the document, in part or in whole, and in any format, solely for noncommercial educational and research purposes. The author and co-authors if applicable retain copyright ownership and moral rights in this document. -

9783110726305.Pdf

Shared Margins ZMO-Studien Studien des Leibniz-Zentrum Moderner Orient Herausgegeben von Ulrike Freitag Band 41 Samuli Schielke and Mukhtar Saad Shehata Shared Margins An Ethnography with Writers in Alexandria after the Revolution This publication was supported by the Leibniz Open Access Monograph Publishing Fund. ISBN 978-3-11-072677-0 e-ISBN (PDF) 978-3-11-072630-5 e-ISBN (EPUB) 978-3-11-072636-7 DOI https://doi.org/10.1515/ 9783110726305 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. For details go to https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ Library of Congress Control Number: 2021937483 Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available in the internet at http://dnb.dnb.de. © 2021 Samuli Schielke and Mukhtar Saad Shehata Cover image: Eman Salah writing in her notebook. Photo by Samuli Schielke, Alexandria, 2015. Printing and binding: CPI books GmbH, Leck www.degruyter.com To Mahmoud Abu Rageh (1971–2018) Contents Acknowledgments ix On names, pronouns, and spelling xiii List of illustrations xiv Introduction: Where is literature? Samuli Schielke 1 Where is literature? 2 Anecdotal evidence 5 Outline of chapters 11 Part I. About writing Samuli Schielke, Mukhtar Saad Shehata 1 Why write, and why not stop? 15 An urge to express 16 ‘Something that has me in it’ 21 Why not stop? 27 A winding path through milieus 31 2 Infrastructures of imagination 39 The formation of scenes 43 A provincial setting 48 The Writers’ Union 51 Mukhtabar al-Sardiyat 54 El Cabina 56 Fabrica 60 Lines of division 63 Milieus at intersection 71 Openings and closures 73 3 The writing of lives 77 Materialities of marginality 79 The symposium as life 84 Being Abdelfattah Morsi 91 How to become a writer in many difficult steps 96 Holding the microphone 101 ‘I hate reality’ 105 ‘It’s a piece of me’ 107 Outsides of power 111 viii Contents Part II. -

INDIAN INSTITUION of TECHNICAL ARBITRATORS New No.4, Old No.36, Loganathan Colony, Mylapore Chennai – 600 004, Tamil Nadu, India Contact No

INDIAN INSTITUION OF TECHNICAL ARBITRATORS New No.4, Old No.36, Loganathan Colony, Mylapore Chennai – 600 004, Tamil Nadu, India Contact No. 098403 58060 Email: [email protected], Website: www.iitarb.org FELLOW: F – 0001 F – 0002 F – 0005 Er. M. C. Bhide Er. O.P. Goel Er. A. Sivasankaran Office Nos. 9 & 10, Gr. Floor, # B-XI / 8091, # 8, 78th Street, Sector 12, Greenland premises C.H.S, Vasant Kunj, K.K. Nagar West, Raikar Marg, New Delhi - 110 070 Chennai – 600 078 Opp. Sitaladevi Temple Road, Tel: Off. 011-26899857, 011- Phone: (O):24714605,(R):24748156, Mahim (W), Mumbai – 400 016 41783104, Mobile: 09810512775, Mobile: 09384748156, Tel: (O) 022-24442190/91/2812 (R) Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] 022-24361009/24314223, Fax: 022 – 2444 2746 Mobile: 9833075895 / 9892358721 Email: [email protected], [email protected] F – 0006 F – 0008 F – 0010 Er. K.D. Arcot Er. K.E. Mohan Er. M. Ulaganathan House No: U-46, No.101, Baskar Colony, No. Old 83 New 34, Plot No: 4185, Virukambakkam, Mandavelli Pakkam Street, Anna Nagar Chennai – 600 092 Mandavelipakham, Chennai – 600 040 Tel: Off: 23765250, Res: 23766039, Chennai – 600 028 Tel: 044-26215052 (O), 044- Fax: 23765560 Tel: 044 24620158, 26215052 (R) Mobile: 09445312074 Fax: 044 28291855, Mobile: 098401 26439 Email: Mobile: 09841158366 Email: [email protected] [email protected] F – 0013 F – 0015 F – 0016 Er. P.C. Pandiyan Er. S.R. Venkataraman Prof.Dr. V. Sundararajulu No.45, Car Nagar B2D, CDS Regal Palm Garden, No.146, (410 old) , Perambur # 383, Tambaram Main Road, 40th Street, TVS Avenue Chennai – 600 011 Velachery, Chennai – 42 Anna Nagar West Extn, Mobile: 098400 27434 Tel: 044-4202 1201, Chennai – 600 101 Email: Mobile: 99626 60622, Tel: Off : 26566565, Res :26544488 [email protected] Email: [email protected] Mobile: 08056098960 E-mail: [email protected] F – 0017 F – 0018 F – 0019 Er. -

Visva-Bharati, Sangit-Bhavana Department of Rabindra Sangit, Dance & Drama CURRICULUM for UNDERGRADUATE COURSE CHOICE BASED CREDIT SYSTEM

Visva-Bharati, Sangit-Bhavana Department of Rabindra Sangit, Dance & Drama CURRICULUM FOR UNDERGRADUATE COURSE CHOICE BASED CREDIT SYSTEM COURSE CODE: DURATION: 3 COURSE CODE SIX SEMESTER BMS YEARS NO: 41 Sl.No Course Semester Credit Marks Full Marks . 1. Core Course - CC 14 Courses I-IV 14X6=84 14X75 1050 08 Courses Practical 06 Courses Theoretical 2. Discipline Specific Elective - DSE 04 Courses V-VI 4X6=24 4X75 300 03 Courses Practical 01 Courses Theoretical 3. Generic Elective Course – GEC 04 Course I-IV 4X6=24 4X75 300 03 Courses Practical 01 Courses Theoretical 4. Skill Enhancement Compulsory Course – SECC III-IV 2X2=4 2X25 50 02 Courses Theoretical 5. Ability Enhancement Compulsory Course – AECC I-II 2X2=4 2X25 50 02 Courses Theoretical 6. Tagore Studies - TS (Foundation Course) I-II 4X2=8 2X50 100 02 Courses Theoretical Total Courses 28 Semester IV Credits 148 Marks 1850 Page 1 of 109 CHOICE BASED CREDIT SYSTEM B.MUS (HONS) COURSE AND MARKS DISTRIBUTION STRUCTURE CC DSE GEC SECC AEC TS SEM C TOTA PRA THE PRA THE PRA THE THE THE THE L C O C O C O O O O I 75 75 - - 75 - - 25 50 300 II 75 75 - - 75 - - 25 50 300 III 150 75 - - 75 - 25 - - 325 IV 150 75 - - - 75 25 - - 325 V 75 75 150 - - - - - - 300 VI 75 75 75 75 - - - - - 300 TOTA 600 450 225 75 225 75 50 50 100 1850 L Page 2 of 109 CHOICE BASED CREDIT SYSTEM B.MUS (HONS) OUTLINE OF THE COURSE STRUCTURE COURSE COURSE TYPE CREDITS MARKS HOURS PER CODE WEEK SEMESTER-I CC-1 PRACTICAL 6 75 12 CC-2 THEORETICAL 6 75 6 GEC-1 PRACTICAL 6 75 12 AECC-1 THEORETICAL 2 25 2 TS-1 THEORETICAL -

Member Directory.Pdf

Index Page No.1 I N D E X FELLOW: S.No. Membership Name Page 45. F – 0148 Bandhu Niranjan Nath 19 Number No. 46. F – 0379 Bandhyopadhyay D.C. 50 1. F – 0117 Abhay Nagnath Rao 15 47. F – 0504 Bangar Raju Pakalapati 68 2. F – 0097 Abraham M.P. 12 48. F – 0238 Bansal H.K. 31 3. F – 0204 Aditya Kumar Singhal 27 49. F – 0517 Basavaraj Koti 70 4. F – 0198 Advani Ram 26 50. F – 0183 Basu Roy S.C. 24 Srinivasarao 51. F – 0274 Bernard Shaw V. 35 5. F – 0031 Agarwal M.K. 4 52. F – 0370 Berry H.C.S. 49 6. F – 0217 Agarwal S.S. 28 53. F – 0490 Bhagwan Singh 66 7. F – 0273 Agrawal Kamlesh 35 54. F – 0435 Bhawani Datt Joshi 58 Kumar 55. F – 0001 Bhide M.C. 1 8. F – 0199 Agrawal.K.N 26 56. F – 0099 Bhupendra J. 13 9. F – 0522 Ajay Kumar Agrawal 70 57. F – 0190 Bindiganavale 25 10. F – 0439 Ajit Ancheri 59 Ramagopal 11. F – 0087 Ajit Baburao Pawar 11 58. F – 0378 Bobbarjung Srinivasa 50 12. F – 0533 Ajit Ulhas Apte 72 Rao 13. F – 0376 Alakh Parshad Aggarwal 50 59. F – 0153 Brig (Retd). 20 14. F – 0418 Alapati Prasad 56 M.A.Siddiqui, VSM 15. F – 0176 Alok Tiwari 23 60. F – 0412 Capt.Mohan A. 55 16. F – 0500 Amar Singh Chauhan 67 61. F – 0024 Chachad D.B. 3 17. F – 0499 Amarendra Kumar Sinha 67 62. F – 0164 Chandra Mohan 21 18.