Brechtian Reading of Usha Ganguli's Play the Journey Within

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hindi Theater Is Not Seen in Any Other Theatre

NATYA SHODH SANSTHAN DISCUSSION ON HINDI THEATRE FROM THE COLLECTIONS OF NATYA SHODH SANSTHAN AUDIO LIBRARY THE PRESENT SCENARIO OF HINDI THEATRE IN CALCUTTA ON th 15 May 1983 AT NATYA SHODH SANSTHAN PARTICIPANTS PRATIBHA AGRAWAL, SAMIK BANDYOPADHYAY, SHIV KUMAR JOSHI, SHYAMANAND JALAN, MANAMOHON THAKORE SHEO KUMAR JHUNJHUNWALA, SWRAN CHOWDHURY, TAPAS SEN, BIMAL LATH, GAYANWATI LATH, SURESH DUTT, PRAMOD SHROFF NATYA SHODH SANSTHAN EE 8, SECTOR 2, SALT LAKE, KOLKATA 91 MAIL : [email protected] Phone (033)23217667 1 NATYA SHODH SANSTHAN Pratibha Agrawal We are recording the discussion on “The present scenario of the Hindi Theatre in Calcutta”. The participants include – Kishen Kumar, Shymanand Jalan, Shiv Kumar Joshi, Shiv Kumar Jhunjhunwala, Manamohan Thakore1, Samik Banerjee, Dharani Ghosh, Usha Ganguly2 and Bimal Lath. We welcome all of you on behalf of Natya Shodh Sansthan. For quite some time we, the actors, directors, critics and the members of the audience have been appreciating and at the same time complaining about the plays that are being staged in Calcutta in the languages that are being practiced in Calcutta, be it in Hindi, English, Bangla or any other language. We felt that if we, the practitioners should sit down and talk about the various issues that are bothering us, we may be able to solve some of the problems and several issues may be resolved. Often it so happens that the artists take one side and the critics-audience occupies the other. There is a clear division – one group which creates and the other who criticizes. Many a time this proves to be useful and necessary as well. -

List of Empanelled Artist

INDIAN COUNCIL FOR CULTURAL RELATIONS EMPANELMENT ARTISTS S.No. Name of Artist/Group State Date of Genre Contact Details Year of Current Last Cooling off Social Media Presence Birth Empanelment Category/ Sponsorsred Over Level by ICCR Yes/No 1 Ananda Shankar Jayant Telangana 27-09-1961 Bharatanatyam Tel: +91-40-23548384 2007 Outstanding Yes https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vwH8YJH4iVY Cell: +91-9848016039 September 2004- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Vrts4yX0NOQ [email protected] San Jose, Panama, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YDwKHb4F4tk [email protected] Tegucigalpa, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SIh4lOqFa7o Guatemala City, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MiOhl5brqYc Quito & Argentina https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=COv7medCkW8 2 Bali Vyjayantimala Tamilnadu 13-08-1936 Bharatanatyam Tel: +91-44-24993433 Outstanding No Yes https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wbT7vkbpkx4 +91-44-24992667 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zKvILzX5mX4 [email protected] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kyQAisJKlVs https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=q6S7GLiZtYQ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WBPKiWdEtHI 3 Sucheta Bhide Maharashtra 06-12-1948 Bharatanatyam Cell: +91-8605953615 Outstanding 24 June – 18 July, Yes https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WTj_D-q-oGM suchetachapekar@hotmail 2015 Brazil (TG) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UOhzx_npilY .com https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SgXsRIOFIQ0 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lSepFLNVelI 4 C.V.Chandershekar Tamilnadu 12-05-1935 Bharatanatyam Tel: +91-44- 24522797 1998 Outstanding 13 – 17 July 2017- No https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ec4OrzIwnWQ -

Minutes of the Meeting of the Expert Committee Held on 14Th, 15Th,17Th and 18Th October, 2013 Under the Performing Arts Grants Scheme (PAGS)

No.F.10-01/2012-P.Arts (Pt.) Ministry of Culture P. Arts Section Minutes of the Meeting of the Expert Committee held on 14th, 15th,17th and 18th October, 2013 under the Performing Arts Grants Scheme (PAGS). The Expert Committee for the Performing Arts Grants Scheme (PAGS) met on 14th, 15th ,17thand 18th October, 2013 to consider renewal of salary grants to existing grantees and decide on the fresh applications received for salary and production grants under the Scheme, including review of certain past cases, as recommended in the earlier meeting. The meeting was chaired by Smt. Arvind Manjit Singh, Joint Secretary (Culture). A list of Expert members present in the meeting is annexed. 2. On the opening day of the meeting ie. 14th October, inaugurating the meeting, Sh. Sanjeev Mittal, Joint Secretary, introduced himself to the members of Expert Committee and while welcoming the members of the committee informed that the Ministry was putting its best efforts to promote, develop and protect culture of the country. As regards the Performing Arts Grants Scheme(earlier known as the Scheme of Financial Assistance to Professional Groups and Individuals Engaged for Specified Performing Arts Projects; Salary & Production Grants), it was apprised that despite severe financial constraints invoked by the Deptt. Of Expenditure the Ministry had ensured a provision of Rs.48 crores for the Repertory/Production Grants during the current financial year which was in fact higher than the last year’s budgetary provision. 3. Smt. Meena Balimane Sharma, Director, in her capacity as the Member-Secretary of the Expert Committee, thereafter, briefed the members about the salient features of various provisions of the relevant Scheme under which the proposals in question were required to be examined by them before giving their recommendations. -

Setting the Stage: a Materialist Semiotic Analysis Of

SETTING THE STAGE: A MATERIALIST SEMIOTIC ANALYSIS OF CONTEMPORARY BENGALI GROUP THEATRE FROM KOLKATA, INDIA by ARNAB BANERJI (Under the Direction of Farley Richmond) ABSTRACT This dissertation studies select performance examples from various group theatre companies in Kolkata, India during a fieldwork conducted in Kolkata between August 2012 and July 2013 using the materialist semiotic performance analysis. Research into Bengali group theatre has overlooked the effect of the conditions of production and reception on meaning making in theatre. Extant research focuses on the history of the group theatre, individuals, groups, and the socially conscious and political nature of this theatre. The unique nature of this theatre culture (or any other theatre culture) can only be understood fully if the conditions within which such theatre is produced and received studied along with the performance event itself. This dissertation is an attempt to fill this lacuna in Bengali group theatre scholarship. Materialist semiotic performance analysis serves as the theoretical framework for this study. The materialist semiotic performance analysis is a theoretical tool that examines the theatre event by locating it within definite material conditions of production and reception like organization, funding, training, availability of spaces and the public discourse on theatre. The data presented in this dissertation was gathered in Kolkata using: auto-ethnography, participant observation, sample survey, and archival research. The conditions of production and reception are each examined and presented in isolation followed by case studies. The case studies bring the elements studied in the preceding section together to demonstrate how they function together in a performance event. The studies represent the vast array of theatre in Kolkata and allow the findings from the second part of the dissertation to be tested across a variety of conditions of production and reception. -

Annual Report

NATIONAL SCHOOL OF DRAMA jk"Vªh; ukV~; fo|ky; ANNUAL REPORT okf"kZd çfrosnu 0 2 - 9 1 0 2 okf"kZd çfrosnu Annual Report 2019-20 Annual Report 2019-20 jk"Vªh; ukV~; fo|ky; National School of Drama Contents NSD : An Introduction 3 Organizational Set-up & Meetings during 2019-20 4 Authorities and Officers of the School 5 Director and other Teaching Staff 6 Training at the National School of Drama 7 Technical Departments 9 Library 10 Highlights 2019-20 13 Other Activities 17 Academic Activities 23 Apprentice Fellowship awarded for the academic year 2019-20 to NSD graduate 36 Students’ Productions 38 Cultural Exchange Programme (CEP) 49 Repertory Company 51 Sanskaar Rang Toli (TIE) 54 National School of Drama Extension Programme 62 RajbhashaVibhag 64 Publication Programme 66 NSD Bengaluru Centre 69 NSD Sikkim Theatre Training Centre, Gangtok 80 NSD Theatre-in-Education Centre, Agartala, Tripura 82 NSD Varanasi Centre 91 Staff strength 97 NSD Resource Position at a Glance 99 National School of Drama National School of Drama (NSD) one of the foremost theatre institutions in the world and the only one of its kind in India was set up by Sangeet Natak Akademy in 1959. Later in 1975, it became an autonomous organization, fully financed by Ministry of Culture, (MoC) Government of India. The objective of NSD is to develop suitable patterns of teaching in all branches of drama both at undergraduate and post-graduate levels so as to establish high standards of theatre education in India. After graduation, the NSD offers a theatre training programme of three years' duration. -

A Complete Profile of Rangroop

MMMAJOR PRODUCTIONS OF RANGRANG----ROOPROOP SINCE THE INCEPTION: Total Name Of The Year No. Of Drama By Directed By Production Shows 1969-70 Michhil 12 Goutam Mukherjee Goutam Mukherjee 1972-73 Akay Akay Sunya 9 Goutam Mukherjee Goutam Mukherjee 1979-80 Kanthaswar 151 Goutam Mukherjee Goutam Mukherjee Sanskrit play: Banabhatta; Adaptation : 1982-83 Kadambari 50 Goutam Mukherjee Dr. K.K. Chakraborty Story: Subodh Ghosh 1984-85 Andhkarer Rang 62 Script: Sima Mukherjee Goutam Mukherjee Story: O’Henry Do. Prahasan 62 Script: K.K. Chakraborty Goutam Mukherjee Story: O’Henry 1987-88 Clown 110 Script: K.K. Chakraborty Goutam Mukherjee 1988-89 Bikalpa 74 Sima Mukhopadhyay Goutam Mukherjee Dwijen Banerjee & 1991-92 Bhanga Boned 130 Sima Mukhopadhyay Saonli Mitra 1992-93 Tringsha Shatabdi 5 Badal Sarkar Kaliprosad Ghosh 1993-94 Boli 11 Tripti Mitra Sima Mukhopadhyay 1994-95 Je Jan Achhey 187 Sima Mukhopadhyay Sima Mukhopadhyay Majhkhane Sima Mukhopadhyay 1996-97 24 Abanindranath Tagore Aalor Phulki & K K Mukhopadhyay Panu Santi Sima Mukhopadhyay Krishna Kishore 1998-99 53 Cheyechhilo (Story: Ramanath Roy) Mukhopadhyay 1999- Aaborto 27 Sima Mukhopadhyay Sima Mukhopadhyay 2000 2000-01 Sunyapat 34 Sima Mukhopadhyay Sima Mukhopadhyay Drama: Olwen Wymark 2002-03 Khnuje Nao 37 Adaptation: Swatilekha Sengupta Rudraprasad Sengupta Je Jan Achhey 2003-04 Majhkhane 32 Sima Mukhopadhyay Sima Mukhopadhyay (Revive) 2004-05 Sesh Raksha 38 Rabindranath Tagore Sima Mukhopadhyay Sima Mukhopadhyay 2005-06 He Mor Debota 10 (Story: Deborshee Sima Mukhopadhyay Saroghee) -

SEAGULL Theatre QUARTERLY 244 Theatrelog Issue 29/30 Jun 2001 Acknowledgements

2 Acknowledgements 3 Introduction 7 ‘My kind of theatre is for the people’ KUMAR ROY 37 ‘And through the poetry we found a new direction’ SHYAMAL GHO S H 59 Minority Culture, Universal Voice RUDRAPRA S AD SEN G UPTA 81 ‘A different kind of confidence and strength’ Editor AS IT MU K HERJEE Anjum Katyal Editorial Consultant Samik Bandyopadhyay 99 Assistants Falling in Love with Theatre Paramita Banerjee ARUN MU K HERJEE Sumita Banerjee Sudeshna Banerjee Sunandini Banerjee 109 Padmini Ray Chaudhury ‘Your own language, your own style’ Vikram Iyengar BI B HA S H CHA K RA B ORTY Design Sunandini Banerjee 149 Photograph used on cover © Nemai Ghosh ‘That tiny cube of space’ MANOJ MITRA 175 ‘A theatre idiom of my own’ AS IT BO S E 197 The Totality of Theatre NIL K ANTHA SEN G UPTA 223 Conversations Published by Naveen Kishore 232 for The Seagull Foundation for the Arts, Appendix I 26 Circus Avenue, Calcutta 700017 Notes on Classic Playtexts Printed at Laurens & Co. 9 Crooked Lane, Calcutta 700 069 234 Appendix II Notes on major Bengali Productions 1944 –-2000 S T Q SEAGULL THeatRE QUARTERLY 244 Theatrelog Issue 29/30 Jun 2001 Acknowledgements Most of the material collected for documentation in this issue of STQ, had already been gathered when work for STQ 27/28 was in progress. We would like to acknowledge with deep gratitude the cooperation we have received from all the theatre directors featured in this issue. We would especially like to thank Shyamal Ghosh and Nilkantha Sengupta for providing a very interesting and rare set of photographs; Mohit Chattopadhyay, Bibhash Chakraborty and Asit Bose for patiently answering our queries; Alok Deb of Pratikriti for providing us the production details of Kenaram Becharam; Abhijit Kar Gupta of Chokh, who has readily answered/ provided the correct sources. -

Ashvamegh Vol.II Issue.XXIII December 2016

About Us: Ashvamegh Vol.II Issue.XXIII December 2016 Ashvamegh Biharsharif, India [email protected], +91 7004831594 Editorial Board on Ashvamegh: Alok Mishra (Editor-in-Chief) Murray Alfredson (Sr. Editor) Dr. Shrikant Singh (Sr. Editor) Nidhi Sharma (Sr. Editor) Vihang Naik (Sr. Editor) Pooja Chakraborty (Editor) Anway Mukhopadhyay (Editor) Munia Khan (Editor) Dr. Sarada Thallam (Sr. Editor) D. Anjan Kumar (Sr. Editor) Ravi Teja (Editor) Advisory Panel on Ashvamegh: Dr. Swarna Prabhat Ken W Simpson N. K. Dar Alan Britt Ashvamegh is an online international journal of literary and creative writing. Publishing monthly, Ashvamegh has successfully launched its 23rd issue in December 2016 (this issue). Submission is open every day of the year. Please visit http://ashvamegh.net for more details. Find Ashvamegh on Facebook Twitter Website Table of Contents: Ashvamegh Vol.II Issue.XXIII December 2016 Cover About Us Authors whose papers have been selected • Dr. M Vishnupriya • Prakash Babu Bodapati • Roohi Rachel D’cruze • A Rajalakshmi • Reeswav Chatterjee • A Harisankar Essays: • Gautam Dhanokar (note: you can download research articles and essays in a different non-fiction edition of the issue from the website) Find Ashvamegh on Facebook Twitter Website Ashvamegh: Vol–II: Issue XXIII: December 2016 Alok Mishra: Editorial ISSN: 2454-4574 What is the best way that you might think of right now if I ask you about teaching the students of English literature? This question was natural to arise because the circumstances that led to this were too much. A week ago or two perhaps, a junior friend, who completed his MA a year after me, came to visit me. -

Brechtian Adaptations in Bengali Group Theatre: Nuances and Controversies

ISSN 2319-5339 IISUniv.J.A. Vol.4(1), 1-10 (2015) Brechtian Adaptations in Bengali Group Theatre: Nuances and Controversies Sib Sankar Abstract Adaptations of Foreign plays in the native tongue had been one of the most contentious issues which concerned Bengali theatre during the last half of the previous centuries even though such adaptations have always been an integral part of its colonial legacy. During the last five decades of the previous century, almost all the major plays of Brecht have been performed in Bengal and by and large the Bengali (alternative) theatre spectators have evinced a remarkable interest in the Brechtian productions. But, rather surprisingly, even by the end of the previous century, Bengali theatre practitioners could not evolve a set of workable principles/methodologies which would appeal to the idiosyncratic ‘taste’ of the native spectators without violating the fundamentals of ‘Dialectical/ Epic Theatre’. In the following few pages of this article, I would like to devote my attention into exploring the issues and concerns regarding the adaptation of Bertolt Brecht’s plays in Bengal. Keywords : adaptation, Dialectical/Epic theatre, native/foreign, familiarization It is very difficult to translate Brecht and make him a success in this country, as people have found out repeatedly. It cannot be otherwise… Utpal Dutt 2009, 24 I think the right approach to adapt Brecht to different peoples of different countries. But to do this, one has to make changes, alteration, even additions to Brecht… Shekhar Chatterjee 1982, 142 Adaptation of foreign language plays in Bengali theatre is a phenomenon which is inextricably linked with it from the time of its inception. -

Bengali Theatre Overview: India Utpal K Banerjee 3 Bengali Theatre Overview: Bangladesh Mumtajuddin Ahmed 9

CONTENTS I—PROLOGUE 1 Bengali Theatre Overview: India Utpal K Banerjee 3 Bengali Theatre Overview: Bangladesh Mumtajuddin Ahmed 9 II—BENGALI THEATRE: LEGACY 19 My Statement Binodini Dasi 21 Golapsundari: The First Actress Debashis Roy Chowdhury 29 Rakhaldas Banerjee: Pioneer Theatre Critic Durga Dutta 33 Girish Chandra Ghosh: Actor and Playwright Samik Bandyopadhyay 37 Girish Chandra and Mythical Plays Samik Bandyopadhyay 41 Views of Sisir Kumar on Theatre Debnarayan Gupta 45 HI—BENGALI THEATRE: EVOLUTION 47 Old Calcutta's English Theatres Kironmoy Raha 49 Nabanna' and Mainstream Theatre Kumar Roy 54 The Theatre of the Post-Thirties Purabi Mukherjee 63 Proscenium Theatre of Bangladesh Ramendu Majumder 65 Changing Role of Theatre in Society Rustam Barucha 72 Evolution Behind the Theatre Curtain Suresh Dutta 78 IV—BENGALI THEATRE: PLURALITY 83 Innovation and Experimentation in Theatre Utpal Dutt 85 Bengali Theatre: The Folk and The Foreign Bibhas Chakraborty 92 The Hijack of Yatra Rudraprasad Sengupta 96 My Narrative Theatre Saoli Mitra 102 Theatre of Politics, Protest and Commitment Bishnupriya Pal 109 Commercial Stage and Group Theatre: Similarities and Contrasts Meghnad Bhattacharjee 120 Bengali Puppet Theatre Sampa Ghosh 125 V—BENGALI THEATRE: EXPRESSION 133 The Sailboat of Fantacy Shyamal Ghosh 135 The Actress: Down the Ages Shova Sen 139 Acting in Multiple Media Mohammad Zakaria 143 Acting and Transcendental Time Debashis Majumdar 147 Advent of New Playwrights Manoj Mitra 153 Terms of Our Art-Form Khaled Choudhury 158 A Tradition of Stagecraft Durga Dutta 170 The Luminous Beginning Tapas Sen 172 VI—INTERACTIONS WITH BENGALI THEATRE 181 The Expanded Theatre Mrinal Sen 183 Bengali Theatre: Persons and Performances J.N. -

A Theatre of Their Own: Indian Women Playwrights in Perspective

A THEATRE OF THEIR OWN: INDIAN WOMEN PLAYWRIGHTS IN PERSPECTIVE A Thesis submitted to the University of North Bengal For the Award of Doctor of Philosophy in English By PINAKI RANJAN DAS Assistant Professor of English Nehru College, Bahadurganj Under the supervision of Dr. ASHIS SENGUPTA Professor Department of English University of North Bengal Department of English University of North Bengal December, 2019 ii iii iv v Abstract In an age where academic curriculum has essentially pushed theatre studies into 'post- script', and the cultural 'space' of making and watching theatre has been largely usurped by the immense popularity of television and 'mainstream' cinemas, it is important to understand why theatre still remains a 'space' to be reckoned as one's 'own'. And to argue for a 'theatre' of 'their own' for the Indian women playwrights (and directors), it is important to explore the possibilities that modern Indian theatre can provide as an instrument of subjective as well as social/ political/ cultural articulations and at the same time analyse the course of Indian theatre which gradually underwent broadening of thematic and dramaturgic scope in order to accommodate the independent voices of the women playwrights and directors. When women playwrights and directors are brought into 'perspective', the social politics concerning women loom large. Though we come across women playwrights like Swarna Kumari Devi, Anurupa Devi or Bimala Sundari Devi in the pre-independence colonial period, it is only from the 1970s onwards that we find a significant population of Indian women playwrights and directors regularly participating in the process of 'theatre making'. -

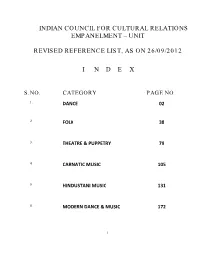

Unit Revised Reference List

INDIAN COUNCIL FOR CULTURAL RELATIONS EMPANELMENT – UNIT REVISED REFERENCE LIST, AS ON 26/09/2012 I N D E X S.NO. CATEGORY PAGE NO 1. DANCE 02 2. FOLK 38 3. THEATRE & PUPPETRY 79 4. CARNATIC MUSIC 105 5. HINDUSTANI MUSIC 131 6. MODERN DANCE & MUSIC 172 1 INDIAN COUNCIL FOR CULTURAL RELATIONS EMPANELMEMT SECTION REVISED REFERENCE LIST FOR DANCE - AS ON 26/09/2012 S.NO. CATEGORY PAGE NO 1. BHARATANATYAM 3 – 11 2. CHHAU 12 – 13 3. KATHAK 14 – 19 4. KATHAKALI 20 – 21 5. KRISHNANATTAM 22 6. KUCHIPUDI 23 – 25 7. KUDIYATTAM 26 8. MANIPURI 27 – 28 9. MOHINIATTAM 29 – 30 10. ODISSI 31 – 35 11. SATTRIYA 36 12. YAKSHAGANA 37 2 REVISED REFERENCE LIST FOR DANCE AS ON 26/09/2012 BHARATANATYAM OUTSTANDING 1. Ananda Shankar Jayant (Also Kuchipudi) (Up) 2007 2. Bali Vyjayantimala 3. Bhide Sucheta 4. Chandershekar C.V. 03.05.1998 5. Chandran Geeta (NCR) 28.10.1994 (Up) August 2005 6. Devi Rita 7. Dhananjayan V.P. & Shanta 8. Eshwar Jayalakshmi (Up) 28.10.1994 9. Govind (Gopalan) Priyadarshini 03.05.1998 10. Kamala (Migrated) 11. Krishnamurthy Yamini 12. Malini Hema 13. Mansingh Sonal (Also Odissi) 14. Narasimhachari & Vasanthalakshmi 03.05.1998 15. Narayanan Kalanidhi 16. Pratibha Prahlad (Approved by D.G March 2004) Bangaluru 17. Raghupathy Sudharani 18. Samson Leela 19. Sarabhai Mallika (Up) 28.10.1994 20. Sarabhai Mrinalini 21. Saroja M K 22. Sarukkai Malavika 23. Sathyanarayanan Urmila (Chennai) 28.10.94 (Up)3.05.1998 24. Sehgal Kiran (Also Odissi) 25. Srinivasan Kanaka 26. Subramanyam Padma 27.