Brechtian Adaptations in Bengali Group Theatre: Nuances and Controversies

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ANNIVERSARY SPECIAL Millenniumpost.In

ANNIVERSARY SPECIAL millenniumpost.in pages millenniumpost NO HALF TRUTHS th28 NEW DELHI & KOLKATA | MAY 2018 Contents “Dharma and Dhamma have come home to the sacred soil of 63 Simplifying Doing Trade this ancient land of faith, wisdom and enlightenment” Narendra Modi's Compelling Narrative 5 Honourable President Ram Nath Kovind gave this inaugural address at the International Conference on Delineating Development: 6 The Bengal Model State and Social Order in Dharma-Dhamma Traditions, on January 11, 2018, at Nalanda University, highlighting India’s historical commitment to ethical development, intellectual enrichment & self-reformation 8 Media: Varying Contours How Central Banks Fail am happy to be here for 10 the inauguration of the International Conference Unmistakable Areas of on State and Social Order 12 Hope & Despair in IDharma-Dhamma Traditions being organised by the Nalanda University in partnership with the Vietnam The Universal Religion Buddhist University, India Foundation, 14 of Swami Vivekananda and the Ministry of External Affairs, Government of India. In particular, Ethical Healthcare: A I must welcome the international scholars and delegates, from 11 16 Collective Responsibility countries, who have arrived here for this conference. Idea of India I understand this is the fourth 17 International Dharma-Dhamma Conference but the first to be hosted An Indian Summer by Nalanda University and in the state 18 for Indian Art of Bihar. In a sense, the twin traditions of Dharma and Dhamma have come home. They have come home to the PMUY: Enlightening sacred soil of this ancient land of faith, 21 Rural Lives wisdom and enlightenment – this land of Lord Buddha. -

Program and Abstracts

Indian Council for Cultural Relations. Consulate General of India in St.Petersburg Russian Academy of Sciences, St.Petersburg scientific center, United Council for Humanities and Social Sciences. Peter the Great Museum of Anthropology and Ethnography (Kunstkamera) RAS. Institute of Oriental Manuscripts RAS. Oriental faculty, St.Petersburg State University. St.Petersburg Association for International cooperation GERASIM LEBEDEV (1749-1817) AND THE DAWN OF INDIAN NATIONAL RENAISSANCE Program and Abstracts Saint-Petersburg, October 25-27, 2018 Индийский совет по культурным связям. Генеральное консульство Индии в Санкт-Петербурге. Российская академия наук, Санкт-Петербургский научный центр, Объединенный научный совет по общественным и гуманитарным наукам. Музей антропологии и этнографии (Кунсткамера) РАН. Институт восточных рукописей РАН Восточный факультет СПбГУ. Санкт-Петербургская ассоциация международного сотрудничества ГЕРАСИМ ЛЕБЕДЕВ (1749-1817) И ЗАРЯ ИНДИЙСКОГО НАЦИОНАЛЬНОГО ВОЗРОЖДЕНИЯ Программа и тезисы Санкт-Петербург, 25-27 октября 2018 г. PROGRAM THURSDAY, OCTOBER 25 St.Peterburg Scientific Centre of the Russian Academy of Sciences, University Embankment 5. 10:30 – 10.55 Participants Registration 11:00 Inaugural Addresses Consul General of India at St. Petersburg Mr. DEEPAK MIGLANI Member of the RAS, Chairman of the United Council for Humanities and Social Sciences NIKOLAI N. KAZANSKY Director of the Peter the Great Museum of Anthropology and Ethnography, Associate Member of the RAS ANDREI V. GOLOVNEV Director of the Institute of Oriental Manuscripts, Professor IRINA F. POPOVA Chairman of the Board, St. Petersburg Association for International Cooperation, MARGARITA F. MUDRAK Head of the Indian Philology Chair, Oriental Faculty, SPb State University, Associate Professor SVETLANA O. TSVETKOVA THURSDAY SESSION. Chaiperson: S.O. Tsvetkova 1. SUDIPTO CHATTERJEE (Kolkata). -

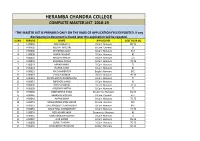

Heramba Chandra College Complete Master List 2018-19

HERAMBA CHANDRA COLLEGE COMPLETE MASTER LIST 2018-19 *THE MASTER LIST IS PREPARED ONLY ON THE BASIS OF APPLICATION FEES DEPOSITED. If any discrepancy in document is found later the application will be rejected. SL NO. FORM ID NAME APPLIED FOR BEST FOUR (%) 1 H00001 RIBHU BAGCHI B.Com Honours 80.75 2 H00002 VEDANT NAGORI B.Com. General 58 3 H00006 INTEKHAB ALAM B.Com Honours 91.5 4 H00009 NABIN BHAGAT B.Com Honours 85 5 H00016 NIKESH CHHETRI B.Com Honours 72.5 6 H00018 MONISHA PANJA B.Com Honours 78.25 7 H00019 ARNAB NANDI B.Com Honours 79 8 H00021 RUPNIL SAHA B.Com Honours 84 9 H00025 KAUSHAMBI ROY English Honours 80.5 10 H00027 LYDIA S KUMAR B.Com Honours 70.75 11 H00031 PUNYA BRATO SANKAR DAS B.Com Honours 77 12 H00035 SHREYOSI NANDI B.Com Honours 90 13 H00036 ROHIT MONDAL B.Com Honours 76.75 14 H00038 ANUBHAV MITRA B.Com Honours 73 15 H00040 SIDDHARTHA SHAW Economics Honours 81.75 16 H00045 SAHANUR HOSSAIN B.Com. General 61.5 17 H00048 ARPAN SAHA B.Com Honours 75.75 18 H00051 MOHAMMAD MOHIUDDIN B.Com. General 58.5 19 H00052 SHOURADEEP CHAKRABORTY B.Com Honours 89.5 20 H00053 IMAN PAUL CHOWDHURY B.Com Honours 74.75 21 H00054 NEELANJAN SAHA Economics Honours 89 22 H00055 ASMIT BANDOPADHYAY B.Com Honours 74 23 H00057 ALIK GAYEN B.Com Honours 85.25 24 H00058 SURAJ THADANI B.Com Honours 70.75 25 H00059 RAJSUBHRA PRAMANIC English Honours 66.25 26 H00060 JAY PRAKASH TIWARY B.Com Honours 89.75 27 H00063 TAPO BRATA SANKAR DAS B.Com Honours 71 28 H00065 PRATIK SEN B.Com Honours 82 29 H00068 AKASH KUMAR SINGH B.Com Honours 73 30 H00073 MAUSAMI SINGH B.Com Honours 83.5 31 H00076 NISSAN DHAR B.Com Honours 80 32 H00078 SUBHAJIT CHAKRABORTY B.Com Honours 78.25 33 H00080 ADARSH ANAND B.Com. -

The Actresses of the Public Theatre in Calcutta in the 19Th & 20Th Century

Revista Digital do e-ISSN 1984-4301 Programa de Pós-Graduação em Letras da PUCRS http://revistaseletronicas.pucrs.br/ojs/index.php/letronica/ Porto Alegre, v. 11, n. esp. (supl. 1), s113-s124, setembro 2018 http://dx.doi.org/10.15448/1984-4301.2018.s.30663 Memory and the written testimony: the actresses of the public theatre in Calcutta in the 19th & 20th century Memória e testemunho escrito: as atrizes do teatro público em Calcutá nos séculos XIX e XX Sarvani Gooptu1 Netaji Institute for Asian Studies, NIAS, in Kolkata, India. 1 Professor in Asian Literary and Cultural Studies ABSTRACT: Modern theatrical performances in Bengali language in Calcutta, the capital of British colonial rule, thrived from the mid-nineteenth at the Netaji Institute for Asian Studies, NIAS, in Kolkata, India. https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1564-1225 E-mail: [email protected] century though they did not include women performers till 1874. The story of the early actresses is difficult to trace due to a lack of evidence in primarycontemporary material sources. and the So scatteredthough a researcher references is to vaguely these legendary aware of their actresses significance in vernacular and contribution journals and to Indian memoirs, theatre, to recreate they have the remained stories of shadowy some of figures – nameless except for those few who have left a written testimony of their lives and activities. It is my intention through the study of this Keywords: Actresses; Bengali Theatre; Social pariahs; Performance and creative output; Memory and written testimony. these divas and draw a connection between testimony and lasting memory. -

Between Violence and Democracy: Bengali Theatre 1965–75

BETWEEN VIOLENCE AND DEMOCRACY / Sudeshna Banerjee / 1 BETWEEN VIOLENCE AND DEMOCRACY: BENGALI THEATRE 1965–75 SUDESHNA BANERJEE 1 The roots of representation of violence in Bengali theatre can be traced back to the tortuous strands of socio-political events that took place during the 1940s, virtually the last phase of British rule in India. While negotiations between the British, the Congress and the Muslim League were pushing the country towards a painful freedom, accompanied by widespread communal violence and an equally tragic Partition, with Bengal and Punjab bearing, perhaps, the worst brunt of it all; the INA release movement, the RIN Mutiny in 1945-46, numerous strikes, and armed peasant uprisings—Tebhaga in Bengal, Punnapra-Vayalar in Travancore and Telengana revolt in Hyderabad—had underscored the potency of popular movements. The Left-oriented, educated middle class including a large body of students, poets, writers, painters, playwrights and actors in Bengal became actively involved in popular movements, upholding the cause of and fighting for the marginalized and the downtrodden. The strong Left consciousness, though hardly reflected in electoral politics, emerged as a weapon to counter State violence and repression unleashed against the Left. A glance at a chronology of events from October 1947 to 1950 reflects a series of violent repressive measures including indiscriminate firing (even within the prisons) that Left movements faced all over the state. The history of post–1964 West Bengal is ridden by contradictions in the manifestation of the Left in representative politics. The complications and contradictions that came to dominate politics in West Bengal through the 1960s and ’70s came to a restive lull with the Left Front coming to power in 1977. -

Hindi Theater Is Not Seen in Any Other Theatre

NATYA SHODH SANSTHAN DISCUSSION ON HINDI THEATRE FROM THE COLLECTIONS OF NATYA SHODH SANSTHAN AUDIO LIBRARY THE PRESENT SCENARIO OF HINDI THEATRE IN CALCUTTA ON th 15 May 1983 AT NATYA SHODH SANSTHAN PARTICIPANTS PRATIBHA AGRAWAL, SAMIK BANDYOPADHYAY, SHIV KUMAR JOSHI, SHYAMANAND JALAN, MANAMOHON THAKORE SHEO KUMAR JHUNJHUNWALA, SWRAN CHOWDHURY, TAPAS SEN, BIMAL LATH, GAYANWATI LATH, SURESH DUTT, PRAMOD SHROFF NATYA SHODH SANSTHAN EE 8, SECTOR 2, SALT LAKE, KOLKATA 91 MAIL : [email protected] Phone (033)23217667 1 NATYA SHODH SANSTHAN Pratibha Agrawal We are recording the discussion on “The present scenario of the Hindi Theatre in Calcutta”. The participants include – Kishen Kumar, Shymanand Jalan, Shiv Kumar Joshi, Shiv Kumar Jhunjhunwala, Manamohan Thakore1, Samik Banerjee, Dharani Ghosh, Usha Ganguly2 and Bimal Lath. We welcome all of you on behalf of Natya Shodh Sansthan. For quite some time we, the actors, directors, critics and the members of the audience have been appreciating and at the same time complaining about the plays that are being staged in Calcutta in the languages that are being practiced in Calcutta, be it in Hindi, English, Bangla or any other language. We felt that if we, the practitioners should sit down and talk about the various issues that are bothering us, we may be able to solve some of the problems and several issues may be resolved. Often it so happens that the artists take one side and the critics-audience occupies the other. There is a clear division – one group which creates and the other who criticizes. Many a time this proves to be useful and necessary as well. -

List of Empanelled Artist

INDIAN COUNCIL FOR CULTURAL RELATIONS EMPANELMENT ARTISTS S.No. Name of Artist/Group State Date of Genre Contact Details Year of Current Last Cooling off Social Media Presence Birth Empanelment Category/ Sponsorsred Over Level by ICCR Yes/No 1 Ananda Shankar Jayant Telangana 27-09-1961 Bharatanatyam Tel: +91-40-23548384 2007 Outstanding Yes https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vwH8YJH4iVY Cell: +91-9848016039 September 2004- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Vrts4yX0NOQ [email protected] San Jose, Panama, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YDwKHb4F4tk [email protected] Tegucigalpa, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SIh4lOqFa7o Guatemala City, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MiOhl5brqYc Quito & Argentina https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=COv7medCkW8 2 Bali Vyjayantimala Tamilnadu 13-08-1936 Bharatanatyam Tel: +91-44-24993433 Outstanding No Yes https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wbT7vkbpkx4 +91-44-24992667 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zKvILzX5mX4 [email protected] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kyQAisJKlVs https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=q6S7GLiZtYQ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WBPKiWdEtHI 3 Sucheta Bhide Maharashtra 06-12-1948 Bharatanatyam Cell: +91-8605953615 Outstanding 24 June – 18 July, Yes https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WTj_D-q-oGM suchetachapekar@hotmail 2015 Brazil (TG) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UOhzx_npilY .com https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SgXsRIOFIQ0 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lSepFLNVelI 4 C.V.Chandershekar Tamilnadu 12-05-1935 Bharatanatyam Tel: +91-44- 24522797 1998 Outstanding 13 – 17 July 2017- No https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ec4OrzIwnWQ -

BPL LIST-KOLKATA MUNICIPAL CORPORATION 004 ULB Name :KOLKATA MC ULB CODE: 79 Ward

BPL LIST-KOLKATA MUNICIPAL CORPORATION Ward No: 004 ULB Name :KOLKATA MC ULB CODE: 79 Member Sl Address Name of Family Head Son/Daughter/Wife of BPL ID Year No Male Female Total 1 11/H/5 PAIK PARA ROW KOL 37 ABHIJEET RUDRA BANAMALI RUDRA 3 1 4 1 2 61/3 B T ROAD ABHIJIT THAKUR T THAKUR 3 2 5 2 3 1/H/29 SARBAKHAN ROAD ABHIRAM MAITI LT NAGENDRA NATH MAITI 2 3 5 3 4 B/1/H/5 R.M.RD,KOL-37 ADALAT RAI LATE BABULAL RAI 3 1 4 4 5 18 DUMDUM ROAD ADHIR BARUI LATE ABINAS BARUI 1 2 3 5 6 SABAKHAN ROAD KOL-37 1/H/11 SABAKHAN ROAD KOL-37 ADHIR CHANDRA KARMAKAR LT PALAN CH KARMAKAR 4 2 6 6 7 1/B/H/1 UMAKANTA SEN LANE,KOL-30 ADHIR HALDER LATE SITA NATH HALDER 5 1 6 7 8 21/39 DUM DUM ROAD ADHIR SARKAR LT.ABHYA SARKAR 3 2 5 8 9 DEWAN BAGAN 11/H/5 PAIK PARA RD. AJAY DAS LT BISWANATH DAS 2 2 4 9 10 RANI HARSHAMUKHEE ROAD 49/H/1B RANI HARSHAMUKHEE ROAD AJAY YADAV LT SANKAR PRASAD YADAV 1 3 4 10 11 R.M. ROAD KOL-37 13/3 R.M. ROAD KOL-37 AJIM AKHTAR LT NABIR RASUL 2 4 6 11 12 GOSHALA 26/59 DUMDUM ROAD,KOL-2 AJIT BALMIKI LATE DHARMA BALMIKI 3 2 5 12 13 9/4 RANI BRUNCH ROAD KOL 2 AJIT DEY LT ANANTA DEY 1 3 4 13 14 1/B UMAKANTA SEN LANE AJIT KR. -

Brechtian Reading of Usha Ganguli's Play the Journey Within

==================================================================== Language in India www.languageinindia.comISSN 1930-2940 Vol. 19:6 June 2019 ==================================================================== Brechtian Reading of Usha Ganguli’s Play The Journey Within Dr. Rahul Kamble Assistant Professor Department of Indian and World Literatures The English and Foreign Languages University, Hyderabad 500007 [email protected] =================================================================== Abstract Usha Ganguli’s play The Journey Within (2000) is a solo performance in which she narrates experiences of her own life in an “autobiographical introspection” mode (Mukherjee 32). The play lays threadbare the journey of her mind and soul since her childhood. The narrative throws light on her own personality, her involvement in theatre, the recurrent themes in the plays directed or performed by her, and her interest in characters and living persons. It also partially reveals Indian ‘theatre-women’s journey’ and women’s theatre in India since early 1970s. However, at no point does the playwright use restrictive personalized narrative nor does she intend the spectators to identify with her emotions, feelings, or anger. Instead she throws, through her reminiscences and character speeches, situational questions at the audience regarding gender inequality, oppression of women, denial of rights, and adverse living conditions. The questions make the spectators examine their own behaviour in similar circumstances, provoke them to resolve, -

Http//:Daathvoyagejournal.Com Editor: Saikat Banerjee Department Of

http//:daathvoyagejournal.com Editor: Saikat Banerjee Department of English Dr. K.N. Modi University, Newai, Rajasthan, India. : An International Journal of Interdisciplinary Studies in English ISSN 2455-7544 www.daathvoyagejournal.com Vol.2, No.3, September, 2017 From Hamlet To Hemlat: Rewriting Shakespeare In Bengal Dr. Mahuya Bhaumik Assistant Professor Department of English Derozio Memorial College, Kolkata, Bengal. Abstract: Production of Shakespeare’s plays in India, particularly Bengal, has an extensive history which dates back to the mid 18th century. Theatre was a tool employed by the British to expose the elites of the Indian society to Western culture and values. Shakespeare was one of the most popular dramatists to be produced in colonial India for concrete reasons. During the latter half of the nineteenth century the productions of Shakespearean plays were marked by a tendency for indigenization thus adding colour colours to them. The latest adaptations of Shakespeare into Bangla are instances of real bold steps taken by the playwrights since these adaptations implant the master text in a completely different politico-cultural milieu, thus subverting the source text in the process. This paper would try to analyse such a process of rewriting Shakespeare in Bangla with special emphasis on Bratya Basu’s Hemlat, The Prince of Garanhata which is an adaptation of Shakespeare’s Hamlet. Key Words: Theatre, Performance, Adaptation, Indigenization, Cross-Culture. Production of Shakespeare’s plays in India, particularly Bengal, has an extensive and rich history which dates back to the mid 18th century. Initially the target audience of these plays was British officials settled here during the colonial days. -

A Tribute to Chetan Datar,Bharangam 13 – All the Plays of B

Snake, Love and Sexuality Ravindra Tripathi’s There are a lot of stories in Indian mythology and folklores where you find the snake or the serpent as sexual motif. Some modern plays are also based upon it. For example Girish Karnad’s play Nagmandala. The snake as sexual motif is not limited only to India. In 13th bharat rang mahotsav, the Japanese play Ugetsu Monogatari (directed by Madoka okada) also presents the snake as a charmer and lover of human being. It is story of 10th century Japan. There is a young man, named Toyoo, son of a fisherman. He lives near seashore. A beautiful woman named Manago comes to his home in a rainy night. Toyoo is attracted towards her. He also lends his umbrella and promises to meet her again in near future. After some days he goes to her house on the pretext of going back his umbrella. During that he gets intimate with her. Manago gives him a beautiful sword as a token of their relationship. But after sometime it comes out that the sword was stolen from a shrine. Toyoo is caught by the officials on the charge of theft. He is taken to the house of Manago and there it is discovered that actually Manago is not a woman but a serpent. She transforms herself as a woman to get Toyoo love. Now the question is what will happen of their relationship. Will Toyoo accept Manago, the serpent as his beloved or leave her? Ugetsu monogatari is a play about coexistence of natural and supernatural in human life. -

Minutes of the Meeting of the Expert Committee Held on 14Th, 15Th,17Th and 18Th October, 2013 Under the Performing Arts Grants Scheme (PAGS)

No.F.10-01/2012-P.Arts (Pt.) Ministry of Culture P. Arts Section Minutes of the Meeting of the Expert Committee held on 14th, 15th,17th and 18th October, 2013 under the Performing Arts Grants Scheme (PAGS). The Expert Committee for the Performing Arts Grants Scheme (PAGS) met on 14th, 15th ,17thand 18th October, 2013 to consider renewal of salary grants to existing grantees and decide on the fresh applications received for salary and production grants under the Scheme, including review of certain past cases, as recommended in the earlier meeting. The meeting was chaired by Smt. Arvind Manjit Singh, Joint Secretary (Culture). A list of Expert members present in the meeting is annexed. 2. On the opening day of the meeting ie. 14th October, inaugurating the meeting, Sh. Sanjeev Mittal, Joint Secretary, introduced himself to the members of Expert Committee and while welcoming the members of the committee informed that the Ministry was putting its best efforts to promote, develop and protect culture of the country. As regards the Performing Arts Grants Scheme(earlier known as the Scheme of Financial Assistance to Professional Groups and Individuals Engaged for Specified Performing Arts Projects; Salary & Production Grants), it was apprised that despite severe financial constraints invoked by the Deptt. Of Expenditure the Ministry had ensured a provision of Rs.48 crores for the Repertory/Production Grants during the current financial year which was in fact higher than the last year’s budgetary provision. 3. Smt. Meena Balimane Sharma, Director, in her capacity as the Member-Secretary of the Expert Committee, thereafter, briefed the members about the salient features of various provisions of the relevant Scheme under which the proposals in question were required to be examined by them before giving their recommendations.