Between Violence and Democracy: Bengali Theatre 1965–75

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ANNIVERSARY SPECIAL Millenniumpost.In

ANNIVERSARY SPECIAL millenniumpost.in pages millenniumpost NO HALF TRUTHS th28 NEW DELHI & KOLKATA | MAY 2018 Contents “Dharma and Dhamma have come home to the sacred soil of 63 Simplifying Doing Trade this ancient land of faith, wisdom and enlightenment” Narendra Modi's Compelling Narrative 5 Honourable President Ram Nath Kovind gave this inaugural address at the International Conference on Delineating Development: 6 The Bengal Model State and Social Order in Dharma-Dhamma Traditions, on January 11, 2018, at Nalanda University, highlighting India’s historical commitment to ethical development, intellectual enrichment & self-reformation 8 Media: Varying Contours How Central Banks Fail am happy to be here for 10 the inauguration of the International Conference Unmistakable Areas of on State and Social Order 12 Hope & Despair in IDharma-Dhamma Traditions being organised by the Nalanda University in partnership with the Vietnam The Universal Religion Buddhist University, India Foundation, 14 of Swami Vivekananda and the Ministry of External Affairs, Government of India. In particular, Ethical Healthcare: A I must welcome the international scholars and delegates, from 11 16 Collective Responsibility countries, who have arrived here for this conference. Idea of India I understand this is the fourth 17 International Dharma-Dhamma Conference but the first to be hosted An Indian Summer by Nalanda University and in the state 18 for Indian Art of Bihar. In a sense, the twin traditions of Dharma and Dhamma have come home. They have come home to the PMUY: Enlightening sacred soil of this ancient land of faith, 21 Rural Lives wisdom and enlightenment – this land of Lord Buddha. -

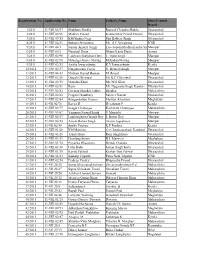

List of Candidates RBU Research Week Phase VII Dates: May 21-27, 2018 Sl.1 Name Subject Tentative Title/Area of Mentor/ Research Supervisor 1

List of Candidates RBU Research Week Phase VII Dates: May 21-27, 2018 Sl.1 Name Subject Tentative Title/Area of Mentor/ Research Supervisor 1. Moumita Biswas Library and Research Output in Md. Ziaur Information Humanities s Reflective Rahaman Sciences through Ph.d Thesis awarded in Rabindra Bharati University: An Analytical Study 2. Satarupa Saha Do Conceptual Transition in Dr. Sudip Ranjan Humanities as Reflected in Hatua DDC 3. Madhushree Do Exploring the Research Md. Ziaur Dutta productivity of Doctoral Rahaman Thesis in LIS Schools of West Bengal upto 2017 4. Musaraf Ali Education Metacognitive Knowledge Dr. Subrata Saha and regulation Patterns Among Science and Social Science Students 5. Proloyendu Do Measuring Emotional Dr. Rajesh Bhoumick Intelligence Kumar Saha 6. Sisir Kumar Do Mathematics Education Dr. Jonaki Sarkar Bhattacharya 7. Sohom Roy Do Rise of Family Language Dr. Bharati Chowdhury Policy and practical in Bhattachaya ESL: A Study of Inter-State Migrant Families in West Bengal 8. Farha Hasan Do Educational Empowerment Dr. Sunil Kumar of Muslim Women in Baskey Birbhum District 9. Arpita Banerjee Political Science Nation and Nationalism – Dr. Bankim A Comparative Analysis of Chandra Mandal the respective Position of Jadunath Sarkar and Rabindranath Tagore. 10. Kingshuk Panda Do Eco-Politics and Problems Dr. Sourish Jha of Coastal Tourism at Digha 11. Rita Dutta Do Cinema and the City: An Prof. Biswanath Interface(1947-19770 Chakraborty 12. Rakesh Ghosh Do Not mentioned Prof. Sabyasachi Basu Ray Chaudhury 13. Joyeeta Das Do Dalit Feminism with Dr. Bankim special Reference to Chandra Mandal Bengali Dalit Literature 14. Manasree Do Good Governance and the Prof. -

Program and Abstracts

Indian Council for Cultural Relations. Consulate General of India in St.Petersburg Russian Academy of Sciences, St.Petersburg scientific center, United Council for Humanities and Social Sciences. Peter the Great Museum of Anthropology and Ethnography (Kunstkamera) RAS. Institute of Oriental Manuscripts RAS. Oriental faculty, St.Petersburg State University. St.Petersburg Association for International cooperation GERASIM LEBEDEV (1749-1817) AND THE DAWN OF INDIAN NATIONAL RENAISSANCE Program and Abstracts Saint-Petersburg, October 25-27, 2018 Индийский совет по культурным связям. Генеральное консульство Индии в Санкт-Петербурге. Российская академия наук, Санкт-Петербургский научный центр, Объединенный научный совет по общественным и гуманитарным наукам. Музей антропологии и этнографии (Кунсткамера) РАН. Институт восточных рукописей РАН Восточный факультет СПбГУ. Санкт-Петербургская ассоциация международного сотрудничества ГЕРАСИМ ЛЕБЕДЕВ (1749-1817) И ЗАРЯ ИНДИЙСКОГО НАЦИОНАЛЬНОГО ВОЗРОЖДЕНИЯ Программа и тезисы Санкт-Петербург, 25-27 октября 2018 г. PROGRAM THURSDAY, OCTOBER 25 St.Peterburg Scientific Centre of the Russian Academy of Sciences, University Embankment 5. 10:30 – 10.55 Participants Registration 11:00 Inaugural Addresses Consul General of India at St. Petersburg Mr. DEEPAK MIGLANI Member of the RAS, Chairman of the United Council for Humanities and Social Sciences NIKOLAI N. KAZANSKY Director of the Peter the Great Museum of Anthropology and Ethnography, Associate Member of the RAS ANDREI V. GOLOVNEV Director of the Institute of Oriental Manuscripts, Professor IRINA F. POPOVA Chairman of the Board, St. Petersburg Association for International Cooperation, MARGARITA F. MUDRAK Head of the Indian Philology Chair, Oriental Faculty, SPb State University, Associate Professor SVETLANA O. TSVETKOVA THURSDAY SESSION. Chaiperson: S.O. Tsvetkova 1. SUDIPTO CHATTERJEE (Kolkata). -

The Actresses of the Public Theatre in Calcutta in the 19Th & 20Th Century

Revista Digital do e-ISSN 1984-4301 Programa de Pós-Graduação em Letras da PUCRS http://revistaseletronicas.pucrs.br/ojs/index.php/letronica/ Porto Alegre, v. 11, n. esp. (supl. 1), s113-s124, setembro 2018 http://dx.doi.org/10.15448/1984-4301.2018.s.30663 Memory and the written testimony: the actresses of the public theatre in Calcutta in the 19th & 20th century Memória e testemunho escrito: as atrizes do teatro público em Calcutá nos séculos XIX e XX Sarvani Gooptu1 Netaji Institute for Asian Studies, NIAS, in Kolkata, India. 1 Professor in Asian Literary and Cultural Studies ABSTRACT: Modern theatrical performances in Bengali language in Calcutta, the capital of British colonial rule, thrived from the mid-nineteenth at the Netaji Institute for Asian Studies, NIAS, in Kolkata, India. https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1564-1225 E-mail: [email protected] century though they did not include women performers till 1874. The story of the early actresses is difficult to trace due to a lack of evidence in primarycontemporary material sources. and the So scatteredthough a researcher references is to vaguely these legendary aware of their actresses significance in vernacular and contribution journals and to Indian memoirs, theatre, to recreate they have the remained stories of shadowy some of figures – nameless except for those few who have left a written testimony of their lives and activities. It is my intention through the study of this Keywords: Actresses; Bengali Theatre; Social pariahs; Performance and creative output; Memory and written testimony. these divas and draw a connection between testimony and lasting memory. -

Hindi Theater Is Not Seen in Any Other Theatre

NATYA SHODH SANSTHAN DISCUSSION ON HINDI THEATRE FROM THE COLLECTIONS OF NATYA SHODH SANSTHAN AUDIO LIBRARY THE PRESENT SCENARIO OF HINDI THEATRE IN CALCUTTA ON th 15 May 1983 AT NATYA SHODH SANSTHAN PARTICIPANTS PRATIBHA AGRAWAL, SAMIK BANDYOPADHYAY, SHIV KUMAR JOSHI, SHYAMANAND JALAN, MANAMOHON THAKORE SHEO KUMAR JHUNJHUNWALA, SWRAN CHOWDHURY, TAPAS SEN, BIMAL LATH, GAYANWATI LATH, SURESH DUTT, PRAMOD SHROFF NATYA SHODH SANSTHAN EE 8, SECTOR 2, SALT LAKE, KOLKATA 91 MAIL : [email protected] Phone (033)23217667 1 NATYA SHODH SANSTHAN Pratibha Agrawal We are recording the discussion on “The present scenario of the Hindi Theatre in Calcutta”. The participants include – Kishen Kumar, Shymanand Jalan, Shiv Kumar Joshi, Shiv Kumar Jhunjhunwala, Manamohan Thakore1, Samik Banerjee, Dharani Ghosh, Usha Ganguly2 and Bimal Lath. We welcome all of you on behalf of Natya Shodh Sansthan. For quite some time we, the actors, directors, critics and the members of the audience have been appreciating and at the same time complaining about the plays that are being staged in Calcutta in the languages that are being practiced in Calcutta, be it in Hindi, English, Bangla or any other language. We felt that if we, the practitioners should sit down and talk about the various issues that are bothering us, we may be able to solve some of the problems and several issues may be resolved. Often it so happens that the artists take one side and the critics-audience occupies the other. There is a clear division – one group which creates and the other who criticizes. Many a time this proves to be useful and necessary as well. -

List of Empanelled Artist

INDIAN COUNCIL FOR CULTURAL RELATIONS EMPANELMENT ARTISTS S.No. Name of Artist/Group State Date of Genre Contact Details Year of Current Last Cooling off Social Media Presence Birth Empanelment Category/ Sponsorsred Over Level by ICCR Yes/No 1 Ananda Shankar Jayant Telangana 27-09-1961 Bharatanatyam Tel: +91-40-23548384 2007 Outstanding Yes https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vwH8YJH4iVY Cell: +91-9848016039 September 2004- https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Vrts4yX0NOQ [email protected] San Jose, Panama, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YDwKHb4F4tk [email protected] Tegucigalpa, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SIh4lOqFa7o Guatemala City, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=MiOhl5brqYc Quito & Argentina https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=COv7medCkW8 2 Bali Vyjayantimala Tamilnadu 13-08-1936 Bharatanatyam Tel: +91-44-24993433 Outstanding No Yes https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wbT7vkbpkx4 +91-44-24992667 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=zKvILzX5mX4 [email protected] https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kyQAisJKlVs https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=q6S7GLiZtYQ https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WBPKiWdEtHI 3 Sucheta Bhide Maharashtra 06-12-1948 Bharatanatyam Cell: +91-8605953615 Outstanding 24 June – 18 July, Yes https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=WTj_D-q-oGM suchetachapekar@hotmail 2015 Brazil (TG) https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=UOhzx_npilY .com https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SgXsRIOFIQ0 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=lSepFLNVelI 4 C.V.Chandershekar Tamilnadu 12-05-1935 Bharatanatyam Tel: +91-44- 24522797 1998 Outstanding 13 – 17 July 2017- No https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ec4OrzIwnWQ -

2011 Batch List of Previous Batch Students.Xlsx

Registration_No Application No. Name Father's Name State/Central Board 1/2011 11-VIII 02/97 Shubham Shukla Ramesh Chandra Shukla Uttaranchal 2/2011 11-VIII 02/96 Madhav Prasad Kamleshwar Prasad Painuli Uttaranchal 3/2011 11-VIII 03/15 KM Shikha Negi Shri Balbeer Singh Uttaranchal 4/2011 11-VIII 04/21 Suhasni Srivastava Mr. S.C Srivastava ICSE 5/2011 11-VIII 04/3 Sapam Amarjit Singh Late Sapam Modhuchandra SinghManipur 6/2011 11-VIII 04/2 Nurutpal Dutta Ghana Kanta Dutta Assam 7/2011 11-VIII 02/98 Laishram Bidyabati Devi L. Bijen Singh Manipur 8/2011 11-VIII 02/90 Makunga Joysee Maring M.Kodun Maring Manipur 9/2011 11-VIII 02/33 Anitha Iswarankutty K.V Iswarankutty Kerala 10/2011 11-VIII 02/37 Ningthoujam Victor N. Hemajit Singh Manipur 11/2011 11-VIII 04/13 Maibam Kamal Hassan M. Iboyal Manipur 12/2011 11-VIII 03/28 Dinesh Chhimwal Mr B.C Chhimwal Uttaranchal 13/2011 11-VIII 03/35 Manisha Khati Mr. M.S Khati Uttaranchal 14/2011 11-VIII 02/81 Rajni Mr. Nagendra Singh Kandari Uttaranchal 15/2011 11-VIII 02/82 Gajanan Shankar Jadhav Shankar Maharashtra 16/2011 11-VIII 02/83 Pragati Chaudhary Sanjeev Kumar Uttaranchal 17/2011 11-VIII 02/84 Ritngenbahun Hoojon Markus Kharbhoi Meghalaya 18/2011 11-VII 02/76 Kavya D Devadasan P Kerala 19/2011 11-VIII 02/77 Sougat Chatterjee Kashinath Chatterjee Maharashtra 20/2011 11-VIII 02/67 Yumnam Nirmal Singh Y Manaobi Manipur 21/2011 11-VIII 04/17 Laiphangbam Gunajit Roy L Iboton Roy Manipur 22/2011 11-VIII 04/14 Amom Rohen Singh Amom Jugeshwor Manipur 23/2011 11-VII 02/48 Sruthy Poulose K P Poulose Kerala -

Secondary Indian Culture and Heritage

Culture: An Introduction MODULE - I Understanding Culture Notes 1 CULTURE: AN INTRODUCTION he English word ‘Culture’ is derived from the Latin term ‘cult or cultus’ meaning tilling, or cultivating or refining and worship. In sum it means cultivating and refining Ta thing to such an extent that its end product evokes our admiration and respect. This is practically the same as ‘Sanskriti’ of the Sanskrit language. The term ‘Sanskriti’ has been derived from the root ‘Kri (to do) of Sanskrit language. Three words came from this root ‘Kri; prakriti’ (basic matter or condition), ‘Sanskriti’ (refined matter or condition) and ‘vikriti’ (modified or decayed matter or condition) when ‘prakriti’ or a raw material is refined it becomes ‘Sanskriti’ and when broken or damaged it becomes ‘vikriti’. OBJECTIVES After studying this lesson you will be able to: understand the concept and meaning of culture; establish the relationship between culture and civilization; Establish the link between culture and heritage; discuss the role and impact of culture in human life. 1.1 CONCEPT OF CULTURE Culture is a way of life. The food you eat, the clothes you wear, the language you speak in and the God you worship all are aspects of culture. In very simple terms, we can say that culture is the embodiment of the way in which we think and do things. It is also the things Indian Culture and Heritage Secondary Course 1 MODULE - I Culture: An Introduction Understanding Culture that we have inherited as members of society. All the achievements of human beings as members of social groups can be called culture. -

A Study of Mahasweta Devi's Urvashi O Johnny

Policies of Survival: Where Happiness Epitomises Freedom... 85 Ars Artium: An International Peer Reviewed-cum-Refereed Research Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences ISSN (Online) : 2395-2423 • ISSN (Print) : 2319-7889 Vol. 6, January 2018 Pp. 85-93 http://www.arsartium.org Policies of Survival: Where Happiness Epitomises Freedom: A Study of Mahasweta Devi’s Urvashi O Johnny –Goutam Karmakar* Abstract The post-independent era of Indian English literature witnesses the emergence of feminine sensibility, and women writers like Kamala Markandaya, Anita Desai, Kamala Das, Manju Kapur, Shashi Deshpande, Mamta Kalia, Gauri Deshpande, Nayantara Sahgal, Bharati Mukherjee, Arundhati Roy, Anita Nair, Eunice De Souza, Sujata Bhatt, Shobha De, Mahasweta Devi and many others try their best for the literary emancipation of not only women but also the marginalized and exploited sections of the society. Among these writers, Mahasweta Devi is one such who recreates a span of history which contains the mechanics of exploitation, depressed communities of India, politico- economical policies of the upper class and social evils and maladies, and for showing all these, she falls in the category of those writers writing in their native languages whose writings are translated regularly into English. An essentially human vision rooted in her imparts a grand encroachment on the contemporary literary scenario. She sings for those whose songs of suffering, prayer, despair, protest and disillusionment are unheard. In her works she tries to give voice to the voiceless and shows the ways to survive and protest. Her Urvashi O Johnny is one such play that deals with survival policies through the character of non-living Urvashi and her owner Johnny, a ventriloquist. -

Minutes of the Meeting of the Expert Committee Held on 14Th, 15Th,17Th and 18Th October, 2013 Under the Performing Arts Grants Scheme (PAGS)

No.F.10-01/2012-P.Arts (Pt.) Ministry of Culture P. Arts Section Minutes of the Meeting of the Expert Committee held on 14th, 15th,17th and 18th October, 2013 under the Performing Arts Grants Scheme (PAGS). The Expert Committee for the Performing Arts Grants Scheme (PAGS) met on 14th, 15th ,17thand 18th October, 2013 to consider renewal of salary grants to existing grantees and decide on the fresh applications received for salary and production grants under the Scheme, including review of certain past cases, as recommended in the earlier meeting. The meeting was chaired by Smt. Arvind Manjit Singh, Joint Secretary (Culture). A list of Expert members present in the meeting is annexed. 2. On the opening day of the meeting ie. 14th October, inaugurating the meeting, Sh. Sanjeev Mittal, Joint Secretary, introduced himself to the members of Expert Committee and while welcoming the members of the committee informed that the Ministry was putting its best efforts to promote, develop and protect culture of the country. As regards the Performing Arts Grants Scheme(earlier known as the Scheme of Financial Assistance to Professional Groups and Individuals Engaged for Specified Performing Arts Projects; Salary & Production Grants), it was apprised that despite severe financial constraints invoked by the Deptt. Of Expenditure the Ministry had ensured a provision of Rs.48 crores for the Repertory/Production Grants during the current financial year which was in fact higher than the last year’s budgetary provision. 3. Smt. Meena Balimane Sharma, Director, in her capacity as the Member-Secretary of the Expert Committee, thereafter, briefed the members about the salient features of various provisions of the relevant Scheme under which the proposals in question were required to be examined by them before giving their recommendations. -

Download (5.2

c m y k c m y k Registered with the Registrar of Newspapers of India: Regd. No. 14377/57 CONTRIBUTORS Dr. Karan Singh Gouranga Dash Madhavilatha Ganji Meena Naik Prof. S. A. Krishnaiah Sampa Ghosh Satish C. Mehta Usha Mailk Utpal K Banerjee Indian Council for Cultural Relations Hkkjrh; lkaLdfrd` lEca/k ifj”kn~ Phone: 91-11-23379309, 23379310, 23379314, 23379930 Fax: 91-11-23378639, 23378647, 23370732, 23378783, 23378830 E-mail: [email protected] Web Site: www.iccrindia.net c m y k c m y k c m y k c m y k Indian Council for Cultural Relations The Indian Council for Cultural Relations (ICCR) was founded on 9th April 1950 by Maulana Abul Kalam Azad, the first Education Minister of independent India. The objectives of the Council are to participate in the formulation and implementation of policies and programmes relating to India’s external cultural relations; to foster and strengthen cultural relations and mutual understanding between India and other countries; to promote cultural exchanges with other countries and people; to establish and develop relations with national and international organizations in the field of culture; and to take such measures as may be required to further these objectives. The ICCR is about a communion of cultures, a creative dialogue with other nations. To facilitate this interaction with world cultures, the Council strives to articulate and demonstrate the diversity and richness of the cultures of India, both in and with other countries of the world. The Council prides itself on being a pre-eminent institution engaged in cultural diplomacy and the sponsor of intellectual exchanges between India and partner countries. -

Playbill-Tiner-Talowar.Pdf

Table of Contents About Natyakrishti-TCAGW 2 Previous Performances 3 Tiner Talowar Management Team 4 Behind the Scene 5 Cast 6 Patrons & Donors 7 Notes from Well-wishers 8 Why Tiner Talowar today? 11 Chasing the Drama? 14 Language of Cinema and Literature 16 Tiner Talowar Prasange 25 Printed by Damodar Printing Kolkata Editor: Suchismita Chattopadhyay Cover and Layout: Kajal Chakraborty & Dilip K. Som Disclaimer: Natyakrishti apologizes for any inadvertent mistakes, omissions and misrepresentations in this publication. www.natyakrishti.org About Natyakrishti-TCAGW Natyakrishti-TCAGW is an amateur theater and cultural group based in the greater Washington D.C., USA. It is a non-profit 501 (c) (3) organization. In 1985, a group of enthusiastic, dedicated theater lovers in the greater Washington area, aspiring to initiate theatrical and cultural activities, formed an amateur drama group. A number of highly acclaimed dramas were staged by the group at the Durgapuja festivals organized by Sanskriti, Inc. of the Washington Metropolitan area. These dramas were also staged in various other cities of the USA. Some of the members concurrently participated in the theatrical and cultural events organized by other groups like Manab Kalyan Kendra, Sanskriti, Mayur, etc. They performed in major roles in the dance dramas Achalayatan and Moha Mudgar, organized by the Hon'ble Ambassador Mr. Siddhartha Shankar Ray, which were staged in Kennedy Center, Gandhi Center and the Indian Embassy in Washington D.C. With a view to developing histrionic talents, active association was initiated with renowned theater groups like Nandikar, Sayak, Calcutta High Court Advocates' Drama Association in India (Hon'ble Minister Ajit Panja's group).