Ashvamegh Vol.II Issue.XXIII December 2016

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hindi Theater Is Not Seen in Any Other Theatre

NATYA SHODH SANSTHAN DISCUSSION ON HINDI THEATRE FROM THE COLLECTIONS OF NATYA SHODH SANSTHAN AUDIO LIBRARY THE PRESENT SCENARIO OF HINDI THEATRE IN CALCUTTA ON th 15 May 1983 AT NATYA SHODH SANSTHAN PARTICIPANTS PRATIBHA AGRAWAL, SAMIK BANDYOPADHYAY, SHIV KUMAR JOSHI, SHYAMANAND JALAN, MANAMOHON THAKORE SHEO KUMAR JHUNJHUNWALA, SWRAN CHOWDHURY, TAPAS SEN, BIMAL LATH, GAYANWATI LATH, SURESH DUTT, PRAMOD SHROFF NATYA SHODH SANSTHAN EE 8, SECTOR 2, SALT LAKE, KOLKATA 91 MAIL : [email protected] Phone (033)23217667 1 NATYA SHODH SANSTHAN Pratibha Agrawal We are recording the discussion on “The present scenario of the Hindi Theatre in Calcutta”. The participants include – Kishen Kumar, Shymanand Jalan, Shiv Kumar Joshi, Shiv Kumar Jhunjhunwala, Manamohan Thakore1, Samik Banerjee, Dharani Ghosh, Usha Ganguly2 and Bimal Lath. We welcome all of you on behalf of Natya Shodh Sansthan. For quite some time we, the actors, directors, critics and the members of the audience have been appreciating and at the same time complaining about the plays that are being staged in Calcutta in the languages that are being practiced in Calcutta, be it in Hindi, English, Bangla or any other language. We felt that if we, the practitioners should sit down and talk about the various issues that are bothering us, we may be able to solve some of the problems and several issues may be resolved. Often it so happens that the artists take one side and the critics-audience occupies the other. There is a clear division – one group which creates and the other who criticizes. Many a time this proves to be useful and necessary as well. -

Brechtian Reading of Usha Ganguli's Play the Journey Within

==================================================================== Language in India www.languageinindia.comISSN 1930-2940 Vol. 19:6 June 2019 ==================================================================== Brechtian Reading of Usha Ganguli’s Play The Journey Within Dr. Rahul Kamble Assistant Professor Department of Indian and World Literatures The English and Foreign Languages University, Hyderabad 500007 [email protected] =================================================================== Abstract Usha Ganguli’s play The Journey Within (2000) is a solo performance in which she narrates experiences of her own life in an “autobiographical introspection” mode (Mukherjee 32). The play lays threadbare the journey of her mind and soul since her childhood. The narrative throws light on her own personality, her involvement in theatre, the recurrent themes in the plays directed or performed by her, and her interest in characters and living persons. It also partially reveals Indian ‘theatre-women’s journey’ and women’s theatre in India since early 1970s. However, at no point does the playwright use restrictive personalized narrative nor does she intend the spectators to identify with her emotions, feelings, or anger. Instead she throws, through her reminiscences and character speeches, situational questions at the audience regarding gender inequality, oppression of women, denial of rights, and adverse living conditions. The questions make the spectators examine their own behaviour in similar circumstances, provoke them to resolve, -

Setting the Stage: a Materialist Semiotic Analysis Of

SETTING THE STAGE: A MATERIALIST SEMIOTIC ANALYSIS OF CONTEMPORARY BENGALI GROUP THEATRE FROM KOLKATA, INDIA by ARNAB BANERJI (Under the Direction of Farley Richmond) ABSTRACT This dissertation studies select performance examples from various group theatre companies in Kolkata, India during a fieldwork conducted in Kolkata between August 2012 and July 2013 using the materialist semiotic performance analysis. Research into Bengali group theatre has overlooked the effect of the conditions of production and reception on meaning making in theatre. Extant research focuses on the history of the group theatre, individuals, groups, and the socially conscious and political nature of this theatre. The unique nature of this theatre culture (or any other theatre culture) can only be understood fully if the conditions within which such theatre is produced and received studied along with the performance event itself. This dissertation is an attempt to fill this lacuna in Bengali group theatre scholarship. Materialist semiotic performance analysis serves as the theoretical framework for this study. The materialist semiotic performance analysis is a theoretical tool that examines the theatre event by locating it within definite material conditions of production and reception like organization, funding, training, availability of spaces and the public discourse on theatre. The data presented in this dissertation was gathered in Kolkata using: auto-ethnography, participant observation, sample survey, and archival research. The conditions of production and reception are each examined and presented in isolation followed by case studies. The case studies bring the elements studied in the preceding section together to demonstrate how they function together in a performance event. The studies represent the vast array of theatre in Kolkata and allow the findings from the second part of the dissertation to be tested across a variety of conditions of production and reception. -

Annual Report

NATIONAL SCHOOL OF DRAMA jk"Vªh; ukV~; fo|ky; ANNUAL REPORT okf"kZd çfrosnu 0 2 - 9 1 0 2 okf"kZd çfrosnu Annual Report 2019-20 Annual Report 2019-20 jk"Vªh; ukV~; fo|ky; National School of Drama Contents NSD : An Introduction 3 Organizational Set-up & Meetings during 2019-20 4 Authorities and Officers of the School 5 Director and other Teaching Staff 6 Training at the National School of Drama 7 Technical Departments 9 Library 10 Highlights 2019-20 13 Other Activities 17 Academic Activities 23 Apprentice Fellowship awarded for the academic year 2019-20 to NSD graduate 36 Students’ Productions 38 Cultural Exchange Programme (CEP) 49 Repertory Company 51 Sanskaar Rang Toli (TIE) 54 National School of Drama Extension Programme 62 RajbhashaVibhag 64 Publication Programme 66 NSD Bengaluru Centre 69 NSD Sikkim Theatre Training Centre, Gangtok 80 NSD Theatre-in-Education Centre, Agartala, Tripura 82 NSD Varanasi Centre 91 Staff strength 97 NSD Resource Position at a Glance 99 National School of Drama National School of Drama (NSD) one of the foremost theatre institutions in the world and the only one of its kind in India was set up by Sangeet Natak Akademy in 1959. Later in 1975, it became an autonomous organization, fully financed by Ministry of Culture, (MoC) Government of India. The objective of NSD is to develop suitable patterns of teaching in all branches of drama both at undergraduate and post-graduate levels so as to establish high standards of theatre education in India. After graduation, the NSD offers a theatre training programme of three years' duration. -

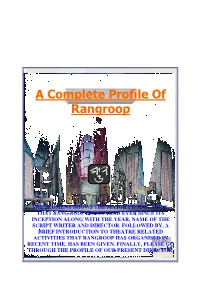

A Complete Profile of Rangroop

MMMAJOR PRODUCTIONS OF RANGRANG----ROOPROOP SINCE THE INCEPTION: Total Name Of The Year No. Of Drama By Directed By Production Shows 1969-70 Michhil 12 Goutam Mukherjee Goutam Mukherjee 1972-73 Akay Akay Sunya 9 Goutam Mukherjee Goutam Mukherjee 1979-80 Kanthaswar 151 Goutam Mukherjee Goutam Mukherjee Sanskrit play: Banabhatta; Adaptation : 1982-83 Kadambari 50 Goutam Mukherjee Dr. K.K. Chakraborty Story: Subodh Ghosh 1984-85 Andhkarer Rang 62 Script: Sima Mukherjee Goutam Mukherjee Story: O’Henry Do. Prahasan 62 Script: K.K. Chakraborty Goutam Mukherjee Story: O’Henry 1987-88 Clown 110 Script: K.K. Chakraborty Goutam Mukherjee 1988-89 Bikalpa 74 Sima Mukhopadhyay Goutam Mukherjee Dwijen Banerjee & 1991-92 Bhanga Boned 130 Sima Mukhopadhyay Saonli Mitra 1992-93 Tringsha Shatabdi 5 Badal Sarkar Kaliprosad Ghosh 1993-94 Boli 11 Tripti Mitra Sima Mukhopadhyay 1994-95 Je Jan Achhey 187 Sima Mukhopadhyay Sima Mukhopadhyay Majhkhane Sima Mukhopadhyay 1996-97 24 Abanindranath Tagore Aalor Phulki & K K Mukhopadhyay Panu Santi Sima Mukhopadhyay Krishna Kishore 1998-99 53 Cheyechhilo (Story: Ramanath Roy) Mukhopadhyay 1999- Aaborto 27 Sima Mukhopadhyay Sima Mukhopadhyay 2000 2000-01 Sunyapat 34 Sima Mukhopadhyay Sima Mukhopadhyay Drama: Olwen Wymark 2002-03 Khnuje Nao 37 Adaptation: Swatilekha Sengupta Rudraprasad Sengupta Je Jan Achhey 2003-04 Majhkhane 32 Sima Mukhopadhyay Sima Mukhopadhyay (Revive) 2004-05 Sesh Raksha 38 Rabindranath Tagore Sima Mukhopadhyay Sima Mukhopadhyay 2005-06 He Mor Debota 10 (Story: Deborshee Sima Mukhopadhyay Saroghee) -

SEAGULL Theatre QUARTERLY 244 Theatrelog Issue 29/30 Jun 2001 Acknowledgements

2 Acknowledgements 3 Introduction 7 ‘My kind of theatre is for the people’ KUMAR ROY 37 ‘And through the poetry we found a new direction’ SHYAMAL GHO S H 59 Minority Culture, Universal Voice RUDRAPRA S AD SEN G UPTA 81 ‘A different kind of confidence and strength’ Editor AS IT MU K HERJEE Anjum Katyal Editorial Consultant Samik Bandyopadhyay 99 Assistants Falling in Love with Theatre Paramita Banerjee ARUN MU K HERJEE Sumita Banerjee Sudeshna Banerjee Sunandini Banerjee 109 Padmini Ray Chaudhury ‘Your own language, your own style’ Vikram Iyengar BI B HA S H CHA K RA B ORTY Design Sunandini Banerjee 149 Photograph used on cover © Nemai Ghosh ‘That tiny cube of space’ MANOJ MITRA 175 ‘A theatre idiom of my own’ AS IT BO S E 197 The Totality of Theatre NIL K ANTHA SEN G UPTA 223 Conversations Published by Naveen Kishore 232 for The Seagull Foundation for the Arts, Appendix I 26 Circus Avenue, Calcutta 700017 Notes on Classic Playtexts Printed at Laurens & Co. 9 Crooked Lane, Calcutta 700 069 234 Appendix II Notes on major Bengali Productions 1944 –-2000 S T Q SEAGULL THeatRE QUARTERLY 244 Theatrelog Issue 29/30 Jun 2001 Acknowledgements Most of the material collected for documentation in this issue of STQ, had already been gathered when work for STQ 27/28 was in progress. We would like to acknowledge with deep gratitude the cooperation we have received from all the theatre directors featured in this issue. We would especially like to thank Shyamal Ghosh and Nilkantha Sengupta for providing a very interesting and rare set of photographs; Mohit Chattopadhyay, Bibhash Chakraborty and Asit Bose for patiently answering our queries; Alok Deb of Pratikriti for providing us the production details of Kenaram Becharam; Abhijit Kar Gupta of Chokh, who has readily answered/ provided the correct sources. -

Brechtian Adaptations in Bengali Group Theatre: Nuances and Controversies

ISSN 2319-5339 IISUniv.J.A. Vol.4(1), 1-10 (2015) Brechtian Adaptations in Bengali Group Theatre: Nuances and Controversies Sib Sankar Abstract Adaptations of Foreign plays in the native tongue had been one of the most contentious issues which concerned Bengali theatre during the last half of the previous centuries even though such adaptations have always been an integral part of its colonial legacy. During the last five decades of the previous century, almost all the major plays of Brecht have been performed in Bengal and by and large the Bengali (alternative) theatre spectators have evinced a remarkable interest in the Brechtian productions. But, rather surprisingly, even by the end of the previous century, Bengali theatre practitioners could not evolve a set of workable principles/methodologies which would appeal to the idiosyncratic ‘taste’ of the native spectators without violating the fundamentals of ‘Dialectical/ Epic Theatre’. In the following few pages of this article, I would like to devote my attention into exploring the issues and concerns regarding the adaptation of Bertolt Brecht’s plays in Bengal. Keywords : adaptation, Dialectical/Epic theatre, native/foreign, familiarization It is very difficult to translate Brecht and make him a success in this country, as people have found out repeatedly. It cannot be otherwise… Utpal Dutt 2009, 24 I think the right approach to adapt Brecht to different peoples of different countries. But to do this, one has to make changes, alteration, even additions to Brecht… Shekhar Chatterjee 1982, 142 Adaptation of foreign language plays in Bengali theatre is a phenomenon which is inextricably linked with it from the time of its inception. -

Bengali Theatre Overview: India Utpal K Banerjee 3 Bengali Theatre Overview: Bangladesh Mumtajuddin Ahmed 9

CONTENTS I—PROLOGUE 1 Bengali Theatre Overview: India Utpal K Banerjee 3 Bengali Theatre Overview: Bangladesh Mumtajuddin Ahmed 9 II—BENGALI THEATRE: LEGACY 19 My Statement Binodini Dasi 21 Golapsundari: The First Actress Debashis Roy Chowdhury 29 Rakhaldas Banerjee: Pioneer Theatre Critic Durga Dutta 33 Girish Chandra Ghosh: Actor and Playwright Samik Bandyopadhyay 37 Girish Chandra and Mythical Plays Samik Bandyopadhyay 41 Views of Sisir Kumar on Theatre Debnarayan Gupta 45 HI—BENGALI THEATRE: EVOLUTION 47 Old Calcutta's English Theatres Kironmoy Raha 49 Nabanna' and Mainstream Theatre Kumar Roy 54 The Theatre of the Post-Thirties Purabi Mukherjee 63 Proscenium Theatre of Bangladesh Ramendu Majumder 65 Changing Role of Theatre in Society Rustam Barucha 72 Evolution Behind the Theatre Curtain Suresh Dutta 78 IV—BENGALI THEATRE: PLURALITY 83 Innovation and Experimentation in Theatre Utpal Dutt 85 Bengali Theatre: The Folk and The Foreign Bibhas Chakraborty 92 The Hijack of Yatra Rudraprasad Sengupta 96 My Narrative Theatre Saoli Mitra 102 Theatre of Politics, Protest and Commitment Bishnupriya Pal 109 Commercial Stage and Group Theatre: Similarities and Contrasts Meghnad Bhattacharjee 120 Bengali Puppet Theatre Sampa Ghosh 125 V—BENGALI THEATRE: EXPRESSION 133 The Sailboat of Fantacy Shyamal Ghosh 135 The Actress: Down the Ages Shova Sen 139 Acting in Multiple Media Mohammad Zakaria 143 Acting and Transcendental Time Debashis Majumdar 147 Advent of New Playwrights Manoj Mitra 153 Terms of Our Art-Form Khaled Choudhury 158 A Tradition of Stagecraft Durga Dutta 170 The Luminous Beginning Tapas Sen 172 VI—INTERACTIONS WITH BENGALI THEATRE 181 The Expanded Theatre Mrinal Sen 183 Bengali Theatre: Persons and Performances J.N. -

A Theatre of Their Own: Indian Women Playwrights in Perspective

A THEATRE OF THEIR OWN: INDIAN WOMEN PLAYWRIGHTS IN PERSPECTIVE A Thesis submitted to the University of North Bengal For the Award of Doctor of Philosophy in English By PINAKI RANJAN DAS Assistant Professor of English Nehru College, Bahadurganj Under the supervision of Dr. ASHIS SENGUPTA Professor Department of English University of North Bengal Department of English University of North Bengal December, 2019 ii iii iv v Abstract In an age where academic curriculum has essentially pushed theatre studies into 'post- script', and the cultural 'space' of making and watching theatre has been largely usurped by the immense popularity of television and 'mainstream' cinemas, it is important to understand why theatre still remains a 'space' to be reckoned as one's 'own'. And to argue for a 'theatre' of 'their own' for the Indian women playwrights (and directors), it is important to explore the possibilities that modern Indian theatre can provide as an instrument of subjective as well as social/ political/ cultural articulations and at the same time analyse the course of Indian theatre which gradually underwent broadening of thematic and dramaturgic scope in order to accommodate the independent voices of the women playwrights and directors. When women playwrights and directors are brought into 'perspective', the social politics concerning women loom large. Though we come across women playwrights like Swarna Kumari Devi, Anurupa Devi or Bimala Sundari Devi in the pre-independence colonial period, it is only from the 1970s onwards that we find a significant population of Indian women playwrights and directors regularly participating in the process of 'theatre making'. -

635301449163371226 IIC ANNUAL REPORT 2013-14 5-3-2014.Pdf

2013-2014 2013 -2014 Annual Report IND I A INTERNAT I ONAL CENTRE 2013-2014 IND I A INTERNAT I ONAL CENTRE New Delhi Board of Trustees Mr. Soli J. Sorabjee, President Justice (Retd.) B.N. Srikrishna Professor M.G.K. Menon Mr. L.K. Joshi Dr. (Smt.) Kapila Vatsyayan Dr. Kavita A. Sharma, Director Mr. N. N. Vohra Executive Members Dr. Kavita A. Sharma, Director Professor Dinesh Singh Mr. K. Raghunath Dr. Biswajit Dhar Dr. (Ms) Sukrita Paul Kumar Cmde.(Retd.) Ravinder Datta, Secretary Cmde.(Retd.) C. Uday Bhaskar Mr. P.R. Sivasubramanian, Hony. Treasurer Mrs. Meera Bhatia Finance Committee Justice (Retd.) B.N. Srikrishna, Dr. Kavita A. Sharma, Director Chairman Mr. P.R. Sivasubramanian, Hony. Treasurer Mr. M. Damodaran Cmde. (Retd.) Ravinder Datta, Secretary Cmde.(Retd.) C. Uday Bhaskar Mr. Ashok K. Chopra, Chief Finance Officer Medical Consultants Dr. K.P. Mathur Dr. Rita Mohan Dr. K.A. Ramachandran Dr. Gita Prakash Dr. Mohammad Qasim IIC Senior Staff Ms Omita Goyal, Chief Editor Mr. A.L. Rawal, Dy. General Manager Dr. S. Majumdar, Chief Librarian Mr. Vijay Kumar, Executive Chef Ms Premola Ghose, Chief, Programme Division Mr. Inder Butalia, Sr. Finance and Accounts Officer Mr. Arun Potdar, Chief, Maintenance Division Ms Hema Gusain, Purchase Officer Mr. Amod K. Dalela, Administration Officer Ms Seema Kohli, Membership Officer Annual Report 2013-2014 It is a privilege to present the 53rd Annual Report of the India International Centre for the period 1 February 2013 to 31 January 2014. The Board of Trustees reconstituted the Finance Committee for the two-year period April 2013 to March 2015 with Justice B.N. -

2021: Interdisciplinary & Transdisciplinary

University of Calgary PRISM: University of Calgary's Digital Repository International Journal of Fear Studies Volume 03: Issue 01, 2021 2021-04-08 International Journal of Fear Studies, Volume 3 (1), 2021: Interdisciplinary & Transdisciplinary Approaches In Search of Fearlessness Research Institute Fisher, R. M., Alex, R. K., & Sachindev, P. S. (eds.) (2021). Interdisciplinary & Transdisciplinary Approaches. International Journal of Fear Studies, 3(1). http://hdl.handle.net/1880/113246 journal Downloaded from PRISM: https://prism.ucalgary.ca International Journal of Fear Studies 3(1) 2021 International Journal of Fear Studies: Interdisciplinary & Transdisciplinary Approaches is an open-access peer-reviewed online journal. IJFS was founded in 2018 by R. Michael Fisher, Ph.D. (Sen. Editor). Its purpose is to promote the interdisciplinary and transdisciplinary study of fear. It is the first journal of its kind with a focus on the nature and role of fear and on innovations in methodologies, pedagogies and research inquiries that expand the fear imaginary beyond what is commonly assumed as how best to know and manage fear. IJFS is an open-access journal stored in PRISM, University of Calgary, AB, Canada. Contents of this journal are copyrighted by the authors and/or artists and should not be reproduced without their permission. Permission is not required for appropriate quote excerpts of material, other than poetry, which are to be used for educational purposes. IJFS is a not-for-profit venture. Any donations or support of energy, time and money are greatly appreciated. Contact: R. Michael Fisher [email protected] Senior Editor – R. Michael Fisher, Ph.D., Director, In Search of Fearlessness Research Institute, Vancouver, BC, Canada Board of Reviewers Four Arrows (Wahinkpe Topa, Don T. -

Refugee?: Bengal Partition in Literature and Cinema

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 8-24-2015 12:00 AM "More or Less" Refugee?: Bengal Partition in Literature and Cinema Sarbani Banerjee The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Prof. Nandi Bhatia The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in Comparative Literature A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Doctor of Philosophy © Sarbani Banerjee 2015 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Comparative Literature Commons, Film and Media Studies Commons, Race, Ethnicity and Post-Colonial Studies Commons, South and Southeast Asian Languages and Societies Commons, and the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Banerjee, Sarbani, ""More or Less" Refugee?: Bengal Partition in Literature and Cinema" (2015). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 3125. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/3125 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. i “MORE OR LESS” REFUGEE? : BENGAL PARTITION IN LITERATURE AND CINEMA (Thesis format: Monograph) by Sarbani Banerjee Graduate Program in Comparative Literature A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The School of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies The University of Western Ontario London, Ontario, Canada © Sarbani Banerjee 2015 ii ABSTRACT In this thesis, I problematize the dominance of East Bengali bhadralok immigrant’s memory in the context of literary-cultural discourses on the Partition of Bengal (1947).