United States Involvement in the Creation and Overthrow of the Somoza Regime

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Political Visions and Historical Scores

Founded in 1944, the Institute for Western Affairs is an interdis- Political visions ciplinary research centre carrying out research in history, political and historical scores science, sociology, and economics. The Institute’s projects are typi- cally related to German studies and international relations, focusing Political transformations on Polish-German and European issues and transatlantic relations. in the European Union by 2025 The Institute’s history and achievements make it one of the most German response to reform important Polish research institution well-known internationally. in the euro area Since the 1990s, the watchwords of research have been Poland– Ger- many – Europe and the main themes are: Crisis or a search for a new formula • political, social, economic and cultural changes in Germany; for the Humboldtian university • international role of the Federal Republic of Germany; The end of the Great War and Stanisław • past, present, and future of Polish-German relations; Hubert’s concept of postliminum • EU international relations (including transatlantic cooperation); American press reports on anti-Jewish • security policy; incidents in reborn Poland • borderlands: social, political and economic issues. The Institute’s research is both interdisciplinary and multidimension- Anthony J. Drexel Biddle on Poland’s al. Its multidimensionality can be seen in published papers and books situation in 1937-1939 on history, analyses of contemporary events, comparative studies, Memoirs Nasza Podróż (Our Journey) and the use of theoretical models to verify research results. by Ewelina Zaleska On the dispute over the status The Institute houses and participates in international research of the camp in occupied Konstantynów projects, symposia and conferences exploring key European questions and cooperates with many universities and academic research centres. -

Rubén Darío A. C. Sandino

Información,Información, análisisanálisis yy debatedebate N oN.o 10. 17, junio-julio agosto-septiembre 2010 2011 Únanse, brillen, secúndense tantos vigores dispersos; formen todos un solo haz de energía ecuménica. Sangre de Hispania fecunda, sólidas, ínclitas razas, muestren los dones pretéritos que fueron antaño su triunfo. Vuelva el antiguo entusiasmo, vuelva el espíritu ardiente que regará lenguas de fuego en esa epifanía. Rubén Darío El amor a mi patria lo he puesto sobre todos los amores y tú debes convencerte que para ser feliz conmigo, es menester que el sol de la libertad brille en nuestras frentes. A. C. Sandino correo agosto- septiembre 2011 año 3 - número 17 - agosto-septiembre 2011 sumario 3 Editorial 4 Ganar las elecciones haciendo Revolución 8 Nicaragua y la importancia de no ser perfumado Correo es una publicación bimestral 13 Logros y desafíos del proyecto sandinista del colectivo de comunicadores “Sandino Vive”, Cómo resurgió el sandinismo en Madriz del Instituto de Comunicación Social. 18 Los materiales publicados por Correo 25 Sandino y las disparidades de sus detractores pueden ser reproducidos total o parcialmente por cualquier medio 31 Un grito mudo de información citando la fuente. 33 Otra ofensiva terrorista contra Cuba Suscripción militante: US$ 50.00 anual 39 El neoliberalismo y los caminos de las izquierdas Precio unitario en Nicaragua: C$ 50.00 41 Ollanta Humala y la oportunidad de Perú 4 Teléfono: 2250 5741 48 Ricardo Morales Avilés [email protected] 53 Cronología de eventos en la historia del FSLN -

Abril 1971 No

VOL. XXVI — N° 127 — Managua, D. N. Nic. — Abril, 1971. SEGUNDA EPOCA DIRECTOR JOAQUIN ZAVALA SUMARIO URTECHO Gerente Administrativo MARCO A. OROZCQ Página Ventas 1. El Mecenazgo de Nuestros Colaboradores, JOSE A. RAMIREZ Lectores y Anunciantes. COLABORADORES 2. Mecenas DE ESTE NUMERO 4. Temas de Viaje. Gaspar Gómez de la Serna Vicente Quadra 10. Gráficas de Viaje: De Europa a América Joaquín Zavala en el Siglo Pasado. Emilio Benard F. Alf. Pellas 14. Del Cofre de la Abuelita Adolfo Calero Portocarrero La Intimidad de Don Vicente. Alberto Ordóñez Argüello Emilio Alvarez Lejarza 20. Fotos Históricas. Dr. Mauricio Pallais Lacayo 20. Luz en un Proyecto de Nicaragua. Dr. Franco Cerutti Luis Mena Solórzano 25. Renuncias a la Presidencia de 3 Personajes Históricos. Créditos Fotográficos Archivo 34. Reelecciones de Actualidad Crisis y Oportunidad. de 36. Rapsodia Hondureña REVISTA CONSERVADORA 38. El Problema del Indio en Nicaragua Prohibida la Reproducción to- tal o parcial sin autorización 44. Fichero del Periodismo Antiguo en Nicaragua del Director. 57. Apuntes Sobre Periodismo Antiguo en Nicaragua. Editada por PUBLICIDAD DE NICARAGUA LIBRO DEL MES: Aptdo. 21-08 — Tel. 2-50-49 En LOS ARQUITECTOS DE LA VICTORIA LIBERAL "Lit. y Edit. Artes Gráficas" Luis Mena Solórzano CORRE CON EL DATSUN OLOR A GASOLINA EL DATSUN 1300 y 1600 tienen: cuatro pago. Solamente en DISTRIBUIDORA puertas • llantas blancas • copas de lujo • DATSUN, S. A., 4 1/2 Carretera Norte, conti- doble bocina • radio • levador de parabrisas a guo a Embotelladora MILCA — Teléfono: chorro • limpia parabrisas de dos velocidades 23251248Q? y 24872. • tapón de gasolina con llave • luces de retro- ceso • doble faro delantero • tapicería de DIDATSA ofrece también vehículos de carga Vinilo • circulación de aire forzada • etc. -

Appendix As Too Inclusive

Color profile: Disabled Composite Default screen Appendix I A Chronological List of Cases Involving the Landing of United States Forces to Protect the Lives and Property of Nationals Abroad Prior to World War II* This Appendix contains a chronological list of pre-World War II cases in which the United States landed troops in foreign countries to pro- tect the lives and property of its nationals.1 Inclusion of a case does not nec- essarily imply that the exercise of forcible self-help was motivated solely, or even primarily, out of concern for US nationals.2 In many instances there is room for disagreement as to what motive predominated, but in all cases in- cluded herein the US forces involved afforded some measure of protection to US nationals or their property. The cases are listed according to the date of the first use of US forces. A case is included only where there was an actual physical landing to protect nationals who were the subject of, or were threatened by, immediate or po- tential danger. Thus, for example, cases involving the landing of troops to punish past transgressions, or for the ostensible purpose of protecting na- tionals at some remote time in the future, have been omitted. While an ef- fort to isolate individual fact situations has been made, there are a good number of situations involving multiple landings closely related in time or context which, for the sake of convenience, have been treated herein as sin- gle episodes. The list of cases is based primarily upon the sources cited following this paragraph. -

JOHN FOSTER DULLES PAPERS PERSONNEL SERIES The

JOHN FOSTER DULLES PAPERS PERSONNEL SERIES The Personnel Series, consisting of approximately 17,900 pages, is comprised of three subseries, an alphabetically arranged Chiefs of Mission Subseries, an alphabetically arranged Special Liaison Staff Subseries and a Chronological Subseries. The entire series focuses on appointments and evaluations of ambassadors and other foreign service personnel and consideration of political appointees for various posts. The series is an important source of information on the staffing of foreign service posts with African- Americans, Jews, women, and individuals representing various political constituencies. Frank assessments of the performances of many chiefs of mission are found here, especially in the Chiefs of Mission Subseries and much of the series reflects input sought and obtained by Secretary Dulles from his staff concerning the political suitability of ambassadors currently serving as well as numerous potential appointees. While the emphasis is on personalities and politics, information on U.S. relations with various foreign countries can be found in this series. The Chiefs of Mission Subseries totals approximately 1,800 pages and contains candid assessments of U.S. ambassadors to certain countries, lists of chiefs of missions and indications of which ones were to be changed, biographical data, materials re controversial individuals such as John Paton Davies, Julius Holmes, Wolf Ladejinsky, Jesse Locker, William D. Pawley, and others, memoranda regarding Leonard Hall and political patronage, procedures for selecting career and political candidates for positions, discussions of “most urgent problems” for ambassadorships in certain countries, consideration of African-American appointees, comments on certain individuals’ connections to Truman Administration, and lists of personnel in Secretary of State’s office. -

Nicaragua's Survival: Choices in a Neoliberal World Stanley G

Old Dominion University ODU Digital Commons Graduate Program in International Studies Theses & Graduate Program in International Studies Dissertations Spring 2006 Nicaragua's Survival: Choices in a Neoliberal World Stanley G. Hash Jr. Old Dominion University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.odu.edu/gpis_etds Part of the Economic Theory Commons, International Relations Commons, Latin American History Commons, and the Latin American Studies Commons Recommended Citation Hash, Stanley G.. "Nicaragua's Survival: Choices in a Neoliberal World" (2006). Doctor of Philosophy (PhD), dissertation, International Studies, Old Dominion University, DOI: 10.25777/m977-a571 https://digitalcommons.odu.edu/gpis_etds/39 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Program in International Studies at ODU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Program in International Studies Theses & Dissertations by an authorized administrator of ODU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. NICARAGUA’S SURVIVAL CHOICES IN A NEOLIBERAL WORLD by Stanley G Hash, Jr B.A. August 1976, University of Maryland M A P. A June 1979, University o f Oklahoma A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of Old Dominion University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirement for the Degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY INTERNATIONAL STUDIES OLD DOMINION UNIVERSITY May 2006 Approved by: Franck_Adams (Director) Lucien Lombardo (Member) Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission. ABSTRACT NICARAGUA’S SURVIVAL: CHOICES IN A NEOLIBERAL WORLD Stanley G Hash, Jr Old Dominion University, 2006 Director: Dr Francis Adams In January 1990 the Nicaraguan electorate chose to abandon the failing Sandinista Revolution in favor of the economic neoliberal rubric. -

Nicaragua's Sandinistas First Took up Arms in 1961, Invoking the Name of Augusto Char Sandino, a General Turned Foe of U.S

Nicaragua's Sandinistas first took up arms in 1961, invoking the name of Augusto Char Sandino, a general turned foe of U.S. intervention in 1927-33. Sandino-here (center) seeking arms in Mexico in 1929 with a Salvadoran Communist ally, Augustm Farabundo Marti (right)-led a hit-and-run war against U.S. Marines. Nearly 1,000 of his men died, but their elusive chief was never caught. WQ NEW YEAR'S 1988 96 Perhaps not since the Spanish Civil War have Americans taken such clearly opposed sides in a conflict in a foreign country. Church orga- nizations and pacifists send volunteers to Nicaragua and lobby against U.S. contra aid; with White House encouragement, conservative out- fits have raised money for the "freedom fighters," in some cases possibly violating U.S. laws against supplying arms abroad. Even after nearly eight years, views of the Sandinista regime's fundamental nature vary widely. Some scholars regard it as far more Marxist-Leninist in rhetoric than in practice. Foreign Policy editor Charles William Maynes argues that Managua's Soviet-backed rulers can be "tamed and contained" via the Central American peace plan drafted by Costa Rica's President Oscar Arias Shchez. Not likely, says Edward N. Luttwak of Washington, D.C.'s Cen- ter for Strategic and International Studies. Expectations that Daniel Ortega and Co., hard pressed as they are, "might actually allow the democratization required" by the Arias plan defy the history of Marx- ist-Leninist regimes. Such governments, says Luttwak, make "tacti- cal accommodations," but feel they must "retain an unchallenged monopoly of power." An opposition victory would be "a Class A political defeat" for Moscow. -

1950 16159 Senate

1950 CONGRESSIONAL -RECORD-SENATE 16159 By Mr. McCARTHY: port No. 3138; to the Committee on House MESSAGES FROM THE PRESIDENT - H. R. 9848. A bill amending the Civil Serv Administration. ice Retirement Act of May 29, 1930, as amend Messages in writing from the Presi ed; to the Committee on Post Office and dent of the United States submitting Civil Service. ·PRIVATE BILLS AND RESOLUTIONS nominations were communicated to the By Mr. BARRETT of Wyoming: Under clause ·1 of rule XXII, private Senate by Mr. Hawks, one of his ~ecre H. R. 9849. A bill granting the consent or· bills and resolutions were introduced and taries. Congress to the States of Idaho, Montana, severally referred as ·follows: Nevada, Oregon, Utah, Washington, and MESSAGE FROM THE HOUSE Wyoming to negotiate and enter into a com By Mr. ALLEN of California: A message from the House of Repre pact for the disposHion, allocation, diversion, H. R. 9858. A blll fo'r the relief of Mr. and sentatives, by Mr. Maurer, one of its· and apportionment of the waters of the Co Mrs. W. A. Kettlewell; to the Committee on the Judiciary. · reading clerks, announced that the House lumbia River and its tributaries, and for had passed a bill <H. R. 9827) to provide other purposes; to the Committee on Public By Mr~ ANGELL: Lands. H. R. 9859. A bill for the relief of Chikako revenue by imposing a corporate excess By Mr. BURDICK: Shishikura Kawata; to the Committee on. profits tax, and ·for other purposes, in H. R. 9850. A bill to increase the rates of the Judiciary. -

The Foreign Service Journal, April 1955

iJPw* lllM wm ■L \ ■pHap^ \\ \ ' / rj|(? V \ \ A \ 1 \\ VvV\-\ m\\\ \ * \ \ |mP ... may I suggest you enjoy the finest whiskey that money can buy 100 PROOF BOTTLED IN BOND Arnctm OsT uNlve«SF((f o<3 VJOUD j IKUM A .■. -V.ED IN B .n>.,v°vt 1N| *&9*. BOTTLED IN BOND KENTUCKY STRAIGHT 4/ KENTUCKY STRAIGHT BOURBON WHISKEY . oiniuto AND tomio IT I w HARPER DISTILLING COWART — lOUliVIUI UNIVCIt- - KENTUCKY STRAIGHT BOURBON WHISKEY, BOTTLED IN BOND, 100 PROOF, I. W. HARPER DISTILLING COMPANY, LOUISVILLE, KENTUCKY World’s finest High Fidelity phonographs and records are RCA’s “New Orthophonic” NEW THRILLS FOR MUSIC-LOVERS! Orthophonic High Fidelity records RCA components and assemble your For the first time—in your own home that capture all the music. And New own unit, or purchase an RCA in¬ —hear music in its full sweep and Orthophonic High Fidelity phono¬ strument complete, ready to plug magnificence! RCA’s half-century graphs reproduce all the music on in and play! For the highest quality research in sound has produced New the records! You may either buy in High Fidelity it’s RCA Victor! ASSEMBLE YOUR OWN SYSTEM. Your choice of RCA READY TO PLUG IN AND PLAY. Complete RCA High intermatched tuners, amplifiers, automatic record Fidelity phonograph features three-speed changer, changers, speakers and cabinets may be easily as¬ 8-inch “Olson-design” speaker, wide-range amplifier, sembled to suit the most critical taste. Use your own separate bass and treble controls. Mahogany or limed cabinets if desired. See your RCA dealer’s catalog. oak finish. -

Cómo Citar El Artículo Número Completo Más Información Del

Revista de Economía Institucional ISSN: 0124-5996 Universidad Externado de Colombia Braden, Spruille EL EMBAJADOR SPRUILLE BRADEN EN COLOMBIA, 1939-1941 Revista de Economía Institucional, vol. 19, núm. 37, 2017, Julio-Diciembre, pp. 265-313 Universidad Externado de Colombia DOI: https://doi.org/10.18601/01245996.v19n37.13 Disponible en: https://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=41956426013 Cómo citar el artículo Número completo Sistema de Información Científica Redalyc Más información del artículo Red de Revistas Científicas de América Latina y el Caribe, España y Portugal Página de la revista en redalyc.org Proyecto académico sin fines de lucro, desarrollado bajo la iniciativa de acceso abierto EL EMBAJADOR SPRUILLE BRADEN EN COLOMBIA, 1939-1941 Spruille Braden* * * * pruille Braden (1894-1978) fue embajador en Colombia entre 1939 y 1942, durante la presidencia de Eduardo Santos. Aprendió el español desdeS niño y conocía bien la cultura latinoamericana. Nació en Elkhor, Montana, pero pasó su infancia en una mina de cobre chilena, de pro- piedad de su padre, ingeniero de grandes dotes empresariales. Regresó a Estados Unidos para cursar su enseñanza secundaria. Estudió en la Universidad de Yale donde, siguiendo el ejemplo paterno, se graduó como ingeniero de minas. Regresó a Chile, trabajó con su padre en proyectos mineros y se casó con una chilena de clase alta. Durante su estadía sura- mericana no descuidó los vínculos políticos con Washington. Participó en la Conferencia de Paz del Chaco, realizada en Buenos Aires (1935-1936), y pasó al mundo de la diplomacia estadounidense, con embajadas en Colombia y en Cuba (1942-1945), donde estrechó lazos con el dictador Fulgencio Batista. -

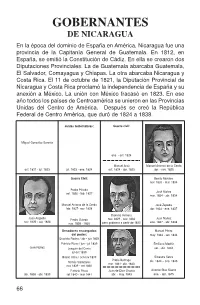

GOBERNANTES DE NICARAGUA En La Época Del Dominio De España En América, Nicaragua Fue Una Provincia De La Capitanía General De Guatemala

GOBERNANTES DE NICARAGUA En la época del dominio de España en América, Nicaragua fue una provincia de la Capitanía General de Guatemala. En 1812, en España, se emitió la Constitución de Cádiz. En ella se crearon dos Diputaciones Provinciales. La de Guatemala abarcaba Guatemala, El Salvador, Comayagua y Chiapas. La otra abarcaba Nicaragua y Costa Rica. El 11 de octubre de 1821, la Diputación Provincial de Nicaragua y Costa Rica proclamó la independencia de España y su anexión a México. La unión con México fracasó en 1823. En ese año todos los países de Centroamérica se unieron en las Provincias Unidas del Centro de América. Después se creó la República Federal de Centro América, que duró de 1824 a 1838. Juntas Gubernativas: Guerra civil: Miguel González Saravia ene. - oct. 1824 Manuel Arzú Manuel Antonio de la Cerda oct. 1821 - jul. 1823 jul. 1823 - ene. 1824 oct. 1824 - abr. 1825 abr. - nov. 1825 Guerra Civil: Benito Morales nov. 1833 - mar. 1834 Pedro Pineda José Núñez set. 1826 - feb. 1827 mar. 1834 - abr. 1834 Manuel Antonio de la Cerda José Zepeda feb. 1827- nov. 1828 abr. 1834 - ene. 1837 Dionisio Herrera Juan Argüello Pedro Oviedo nov. 1829 - nov. 1833 Juan Núñez nov. 1825 - set. 1826 nov. 1828 - 1830 pero gobierna a partir de 1830 ene. 1837 - abr. 1838 Senadores encargados Manuel Pérez del poder: may. 1843 - set. 1844 Evaristo Rocha / abr - jun 1839 Patricio Rivas / jun - jul 1839 Emiliano Madriz José Núñez Joaquín del Cosío set. - dic. 1844 jul-oct 1839 Hilario Ulloa / oct-nov 1839 Silvestre Selva Pablo Buitrago Tomás Valladares dic. -

Isbn 978-83-232-2284-2 Issn 1733-9154

Managing Editor: Marek Paryż Editorial Board: Paulina Ambroży-Lis, Patrycja Antoszek, Zofia Kolbuszewska, Karolina Krasuska, Zuzanna Ładyga Advisory Board: Andrzej Dakowski, Jerzy Durczak, Joanna Durczak, Jerzy Kutnik, Zbigniew Lewicki, Elżbieta Oleksy, Agata Preis-Smith, Tadeusz Rachwał, Agnieszka Salska, Tadeusz Sławek, Marek Wilczyński Reviewers for Vol. 5: Tomasz Basiuk, Mirosława Buchholtz, Jerzy Durczak, Joanna Durczak, Jacek Gutorow, Paweł Frelik, Jerzy Kutnik, Jadwiga Maszewska, Zbigniew Mazur, Piotr Skurowski Polish Association for American Studies gratefully acknowledges the support of the Polish-U.S. Fulbright Commission in the publication of the present volume. © Copyright for this edition by Wydawnictwo Naukowe UAM, Poznań 2011 Cover design: Ewa Wąsowska Production editor: Elżbieta Rygielska ISBN 978-83-232-2284-2 ISSN 1733-9154 WYDAWNICTWO NAUKOWE UNIWERSYTETU IM. ADAMA MICKIEWICZA 61-701 POZNAŃ, UL. FREDRY 10, TEL. 061 829 46 46, FAX 061 829 46 47 www.press.amu.edu.pl e-mail:[email protected] Ark. wyd.16,00. Ark. druk. 13,625. DRUK I OPRAWA: WYDAWNICTWO I DRUKARNIA UNI-DRUK s.j. LUBOŃ, UL PRZEMYSŁOWA 13 Table of Contents Julia Fiedorczuk The Problems of Environmental Criticism: An Interview with Lawrence Buell ......... 7 Andrea O’Reilly Herrera Transnational Diasporic Formations: A Poetics of Movement and Indeterminacy ...... 15 Eliud Martínez A Writer’s Perspective on Multiple Ancestries: An Essay on Race and Ethnicity ..... 29 Irmina Wawrzyczek American Historiography in the Making: Three Eighteenth-Century Narratives of Colonial Virginia ........................................................................................................ 45 Justyna Fruzińska Emerson’s Far Eastern Fascinations ........................................................................... 57 Małgorzata Grzegorzewska The Confession of an Uncontrived Sinner: Edgar Allan Poe’s “The Tell-Tale Heart” 67 Tadeusz Pióro “The death of literature as we know it”: Reading Frank O’Hara ...............................