Female Issues and Relationship Constellations. the Literary World Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Toon Boom Harmony 12.2 Play Guide

Toon Boom Harmony 12.2.1 Play Guide Legal Notices Toon Boom Animation Inc. 4200 Saint-Laurent, Suite 1020 Montreal, Quebec, Canada H2W 2R2 Tel: +1 514 278 8666 Fax: +1 514 278 2666 toonboom.com Disclaimer The content of this guide is covered by a specific limited warranty and exclusions and limit of liability under the applicable License Agreement as supplemented by the special terms and conditions for Adobe®Flash® File Format (SWF). For details, refer to the License Agreement and to those special terms and conditions. The content of this guide is the property of Toon Boom Animation Inc. and is copyrighted. Any reproduction in whole or in part is strictly prohibited. Trademarks Harmony is a trademark of Toon Boom Animation Inc. Publication Date 7/6/2018 Copyright © 2016 Toon Boom Animation Inc. All rights reserved. 2 Harmony 12.2 Play Guide Contents Toon Boom Harmony 12.2.1 Play Guide 1 Contents 3 Chapter 1: Using Toon Boom Play 4 Starting Toon Boom Play 5 About Toon Boom Play 6 Loading an Image Sequence 8 Toon Boom Play Playback Toolbar 11 Toon Boom Play Commands 13 Glossary 17 3 Chapter 1: Using Toon Boom Play Chapter 1: Using Toon Boom Play The Toon Boom Play module is designed specifically for playing back and viewing animated projects once they have been rendered out into image sequences. This module opens directly from your program menu to load your final render. It's also used when playing back a scene with effects in Harmony. This section is divided as follows: Starting Toon Boom Play 5 About Toon Boom Play 6 Loading an Image Sequence 8 Toon Boom Play Playback Toolbar 11 Toon Boom Play Commands 13 4 Harmony 12.2 Play Guide Starting Toon Boom Play Before using Toon Boom Play, you must start the program. -

February 2020 Ajet

AJET News & Events, Arts & Culture, Lifestyle, Community FEBRUARY 2020 Riding the Jiu-Jitsu Wave Working for the Kyoryokutai The Changing Colors of the Red and White Singing Battle Journey Through Magic Embarrassing Adventures of an Expat in Tokyo The Japanese Lifestyle & Culture Magazine Written by the International Community in Japan1 In response to ongoing global news, the team at Connect Magazine would like to acknowledge the devastating impact of the 2019-2020 bushfires in Australia. Our thoughts and support are with those suffering. 2 Since September 2019, the raging fires across the eastern and southeastern Australian coastal regions have burned over 17.9 million acres, destroyed over 2000 homes, and killed least 27 people. A billion animals have been caught in the fires, with some species now pushed to the brink of extinction. Skies are reddened from air heavy with smoke— smoke which can be seen 2,000km away in New Zealand and even from Chile, South America, which is more than 11,000km away. Currently, massive efforts are being taken to tackle the bushfires and protect people, animals, and homes in the vicinity. If you would like to be a part of this effort, here are some resources you can use to help: Country Fire Authority Country Fire Service Foundation In Victoria In South Australia New South Wales Rural The Australian Red Cross Fire Service Fire recovery and relief fund World Wildlife Fund GIVIT Caring for injured wildlife and Donating items requested by habitat restoration those affected The Animal Rescue Collective Craft Guild Making bedding and bandaging for injured animals. -

Old Witchcraft Secrets.Pdf

1 www.oldwitchcraft.com 2 Hi. I’d like to thank you once again for getting my book. You are about to discover amazing rituals, spells and knowledge that have been used for centuries by authentic witchcraft practitioners. I’m very happy that for many of my readers this book had made a tremendous difference in their lives. I hope it will help you too… Bob www.oldwitchcraft.com 3 Index I. Introduction ....................................................................pag 4 II. Getting Started 1. Book Of Shadows .......................................................pag 5 2. Rituals .......................................................................pag 6 3. Basic Parts of a Ritual ........................................... .....pag 6 4. Magick Circle Revealed .................................. ............pag 8 5. Magick Pentagram Revealed .......................................pag 10 6. Artificial Elementals ....................................................pag 12 III. How to Cast Spells 1. How to make spells work ............................................pag 13 2. Timing ......................................................................pag 14 IV. Astral Projection Revealed ...............................................pag 15 V. Aura Revealed ................................................................pag 19 VI. Dragon Magick ...............................................................pag 21 VII. Spells 1. Love Spells ................................................................pag 30 2. Protection Spells ........................................................pag -

The Literature of Kita Morio DISSERTATION Presented In

Insignificance Given Meaning: The Literature of Kita Morio DISSERTATION Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Masako Inamoto Graduate Program in East Asian Languages and Literatures The Ohio State University 2010 Dissertation Committee: Professor Richard Edgar Torrance Professor Naomi Fukumori Professor Shelley Fenno Quinn Copyright by Masako Inamoto 2010 Abstract Kita Morio (1927-), also known as his literary persona Dokutoru Manbô, is one of the most popular and prolific postwar writers in Japan. He is also one of the few Japanese writers who have simultaneously and successfully produced humorous, comical fiction and essays as well as serious literary works. He has worked in a variety of genres. For example, The House of Nire (Nireke no hitobito), his most prominent work, is a long family saga informed by history and Dr. Manbô at Sea (Dokutoru Manbô kôkaiki) is a humorous travelogue. He has also produced in other genres such as children‟s stories and science fiction. This study provides an introduction to Kita Morio‟s fiction and essays, in particular, his versatile writing styles. Also, through the examination of Kita‟s representative works in each genre, the study examines some overarching traits in his writing. For this reason, I have approached his large body of works by according a chapter to each genre. Chapter one provides a biographical overview of Kita Morio‟s life up to the present. The chapter also gives a brief biographical sketch of Kita‟s father, Saitô Mokichi (1882-1953), who is one of the most prominent tanka poets in modern times. -

The Last Man"

W&M ScholarWorks Undergraduate Honors Theses Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 5-2016 Renegotiating the Apocalypse: Mary Shelley’s "The Last Man" Kathryn Joan Darling College of William and Mary Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses Part of the Literature in English, British Isles Commons Recommended Citation Darling, Kathryn Joan, "Renegotiating the Apocalypse: Mary Shelley’s "The Last Man"" (2016). Undergraduate Honors Theses. Paper 908. https://scholarworks.wm.edu/honorstheses/908 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Undergraduate Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. 1 The apocalypse has been written about as many times as it hasn’t taken place, and imagined ever since creation mythologies logically mandated destructive counterparts. Interest in the apocalypse never seems to fade, but what does change is what form that apocalypse is thought to take, and the ever-keen question of what comes after. The most classic Western version of the apocalypse, the millennial Judgement Day based on Revelation – an absolute event encompassing all of humankind – has given way in recent decades to speculation about political dystopias following catastrophic war or ecological disaster, and how the remnants of mankind claw tooth-and-nail for survival in the aftermath. Desolate landscapes populated by cannibals or supernatural creatures produce the awe that sublime imagery, like in the paintings of John Martin, once inspired. The Byronic hero reincarnates in an extreme version as the apocalyptic wanderer trapped in and traversing a ruined world, searching for some solace in the dust. -

Et Table of Contents Foreword

by Kriket Table of Contents Foreword............................................................................................................................................................... 4 Introduction .......................................................................................................................................................... 5 How to Smudge ..................................................................................................................................................... 6 Practical Example: Smudging a Room or House ............................................................................................... 7 As Medicine .......................................................................................................................................................... 9 Reading the Smoke and Ashes ............................................................................................................................ 10 Tones ................................................................................................................................................................... 11 What are Tones? ............................................................................................................................................. 11 High Tones ...................................................................................................................................................... 11 Mid Tones ...................................................................................................................................................... -

Writing As Aesthetic in Modern and Contemporary Japanese-Language Literature

At the Intersection of Script and Literature: Writing as Aesthetic in Modern and Contemporary Japanese-language Literature Christopher J Lowy A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Washington 2021 Reading Committee: Edward Mack, Chair Davinder Bhowmik Zev Handel Jeffrey Todd Knight Program Authorized to Offer Degree: Asian Languages and Literature ©Copyright 2021 Christopher J Lowy University of Washington Abstract At the Intersection of Script and Literature: Writing as Aesthetic in Modern and Contemporary Japanese-language Literature Christopher J Lowy Chair of the Supervisory Committee: Edward Mack Department of Asian Languages and Literature This dissertation examines the dynamic relationship between written language and literary fiction in modern and contemporary Japanese-language literature. I analyze how script and narration come together to function as a site of expression, and how they connect to questions of visuality, textuality, and materiality. Informed by work from the field of textual humanities, my project brings together new philological approaches to visual aspects of text in literature written in the Japanese script. Because research in English on the visual textuality of Japanese-language literature is scant, my work serves as a fundamental first-step in creating a new area of critical interest by establishing key terms and a general theoretical framework from which to approach the topic. Chapter One establishes the scope of my project and the vocabulary necessary for an analysis of script relative to narrative content; Chapter Two looks at one author’s relationship with written language; and Chapters Three and Four apply the concepts explored in Chapter One to a variety of modern and contemporary literary texts where script plays a central role. -

1998 Acquisitions

1998 Acquisitions PAINTINGS PRINTS Carl Rice Embrey, Shells, 1972. Acrylic on panel, 47 7/8 x 71 7/8 in. Albert Belleroche, Rêverie, 1903. Lithograph, image 13 3/4 x Museum purchase with funds from Charline and Red McCombs, 17 1/4 in. Museum purchase, 1998.5. 1998.3. Henry Caro-Delvaille, Maternité, ca.1905. Lithograph, Ernest Lawson, Harbor in Winter, ca. 1908. Oil on canvas, image 22 x 17 1/4 in. Museum purchase, 1998.6. 24 1/4 x 29 1/2 in. Bequest of Gloria and Dan Oppenheimer, Honoré Daumier, Ne vous y frottez pas (Don’t Meddle With It), 1834. 1998.10. Lithograph, image 13 1/4 x 17 3/4 in. Museum purchase in memory Bill Reily, Variations on a Xuande Bowl, 1959. Oil on canvas, of Alexander J. Oppenheimer, 1998.23. 70 1/2 x 54 in. Gift of Maryanne MacGuarin Leeper in memory of Marsden Hartley, Apples in a Basket, 1923. Lithograph, image Blanche and John Palmer Leeper, 1998.21. 13 1/2 x 18 1/2 in. Museum purchase in memory of Alexander J. Kent Rush, Untitled, 1978. Collage with acrylic, charcoal, and Oppenheimer, 1998.24. graphite on panel, 67 x 48 in. Gift of Jane and Arthur Stieren, Maximilian Kurzweil, Der Polster (The Pillow), ca.1903. 1998.9. Woodcut, image 11 1/4 x 10 1/4 in. Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Frederic J. SCULPTURE Oppenheimer in memory of Alexander J. Oppenheimer, 1998.4. Pierre-Jean David d’Angers, Philopoemen, 1837. Gilded bronze, Louis LeGrand, The End, ca.1887. Two etching and aquatints, 19 in. -

Inciting Difference and Distance in the Writings of Sakiyama Tami, Yi Yang-Ji, and Tawada Yōko

Inciting Difference and Distance in the Writings of Sakiyama Tami, Yi Yang-ji, and Tawada Yōko Victoria Young Submitted in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Leeds School of East Asian Studies, School of Languages, Cultures and Societies March 2016 ii The candidate confirms that the work submitted is her own and that appropriate credit has been given where reference has been made to the work of others. This copy has been supplied on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. © 2016 The University of Leeds and Victoria Young iii Acknowledgements The first three years of this degree were fully funded by a Postgraduate Studentship provided by the academic journal Japan Forum in conjunction with BAJS (British Association for Japanese Studies), and a University of Leeds Full Fees Bursary. My final year maintenance costs were provided by a GB Sasakawa Postgraduate Studentship and a BAJS John Crump Studentship. I would like to express my thanks to each of these funding bodies, and to the University of Leeds ‘Leeds for Life’ programme for helping to fund a trip to present my research in Japan in March 2012. I am incredibly thankful to many people who have supported me on the way to completing this thesis. The diversity offered within Dr Mark Morris’s literature lectures and his encouragement as the supervisor of my undergraduate dissertation in Cambridge were both fundamental factors in my decision to pursue further postgraduate studies, and I am indebted to Mark for introducing me to my MA supervisor, Dr Nicola Liscutin. -

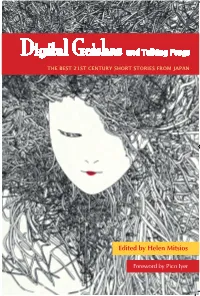

Digital Geishas Sample 4.Pdf

Literature/Asian Studies Digital Geishas Digital Digital Geishas and Talking Frogs THE BEST 21ST CENTURY SHORT STORIES FROM JAPAN Digital Geishas and Talking Frogs With a foreword by Pico Iyer and Talking Frogs THE BEST 21ST CENTURY SHORT STORIES FROM JAPAN This collection of short stories features the most up-to-date and exciting writing from the most popular and celebrated authors in Japan today. These wildly imaginative and boundary-bursting stories reveal fascinating and unexpected personal responses to the changes raging through today’s Japan. Along with some of the THE BEST 21 world’s most renowned Japanese authors, Digital Geishas and Talking Frogs includes many writers making their English-language debut. ST “Great stories rewire your brain, and in these tales you can feel your mind C E shifting as often as Mizue changes trains at the Shinagawa station in N T ‘My Slightly Crooked Brooch…’ The contemporary short stories in this URY SHO collection, at times subversive, astonishing and heart-rending, are brimming with originality and genius.” R —David Dalton, author of Pop: The Genius of Andy Warhol T STO R “Here are stories that arrive from our global future, made from shards IES FR of many local, personal pasts. In the age of anime, amazingly, Japanese literature thrives.” O M JAPAN —Paul Anderer, Professor of Japanese, Columbia University About the Editor H EDITED BY Helen Mitsios is the editor of New Japanese Voices: The Best Contemporary Fiction from Japan, which was twice listed as a New York Times Book Review Editors’ Choice. She has recently co-authored the memoir Waltzing with the Enemy: A Mother and Daughter Confront the Aftermath of the Holocaust. -

18483 19 18486 Ai 2017 Ai 18319 Ai 2031 Aiko 18580 Alan 18485

ALDEBARAN KARAOKE Catálogo de Músicas - Por ordem de INTÉRPRETE Código INTÉRPRETE MÚSICA 18483 19 ANO KAMI HIKOHKI KUMORIZORA WATTE 18424 ABE SHIZUE MIZU IRO NO TEGAMI 18486 AI BELIEVE 2017 AI STORY 18319 AI YOU ARE MY STAR 5103 AI JOHJI & SHIKI CHINAMI AKAI GLASS 5678 AIKAWA NANASE BYE BYE 5815 AIKAWA NANASE SWEET EMOTION 5645 AIKAWA NANASE YUME MIRU SHOJYOJYA IRARENAI 2031 AIKO KABUTO MUSHI 2015 AKIKAWA MASAFUMI SEN NO KAZE NI NATTE 2022 AKIMOTO JUNKO AI NO MAMA DE 2124 AKIMOTO JUNKO AME NO TABIBITO 2011 AKIMOTO JUNKO MADINSON GUN NO KOI 18233 AKIMOTO JUNKO TASOGARE LOVE AGAIN 18562 AKIOKA SHUJI AIBOH ZAKE 2296 AKIOKA SHUJI OTOKO NO TABIJI 18432 AKIOKA SHUJI SAKE BOJO 18580 ALAN KUON NO KAWA 18485 ALAN NAMONAKI KOI NO UTA 5117 ALICE FUYU NO INAZUMA 2266 ALICE IMA WA MOH DARE MO 18279 AMANE KAORU TAIYOH NO UTA 5658 AMI SUZUKI ALONE IN MY ROOM 2223 AMIN MATSU WA 5340 AMURO NAMIE CAN YOU CELEBRATE 5341 AMURO NAMIE CHASE THE CHANCE 18536 AMURO NAMIE FIGHT TOGETHER 5711 AMURO NAMIE I HAVE NEVER SEEN 5766 AMURO NAMIE NEVER END 5798 AMURO NAMIE SAY THE WORD 5294 AMURO NAMIE STOP THE MUSIC 5820 AMURO NAMIE THINK OF ME 5300 AMURO NAMIE TRY ME (WATASHI O SHINJITE) 5838 AMURO NAMIE WISHING ON THE SAME STAR 18425 AN CAFÉ NATSU KOI NATSU GAME 18574 ANGELA AKI HOME 18296 ANGELA AKI KAGAYAKU HITO 18211 ANGELA AKI KISS ME GOODBYE 18224 ANGELA AKI RAIN 18552 ANGELA AKI SAKURA IRO 2360 ANGELA AKI TEGAMI ~ HAIKEI JUHGO NO KIMI E 2040 ANGELA AKI THIS LOVE 18358 ANGELA AKI WE'RE ALL ALONE 2258 ANN LEWIS GOODBYE MY LOVE 5494 ANN LOUISE WOMAN 2379 ANRI OLIVIA -

Teachers Guide to the High Water Mark Initiative

In an effort to make residents aware of flood risks and encourage them to take action to reduce risk, many of Monmouth County’s coastal communities are participating in the Monmouth County High Water Mark Initiative. Through this initiative the County and its partners have recently placed nearly 100 high water mark signs throughout 14 towns and 2 federal sites. The High Water Mark (HWM) Initiative is a component of the National Flood Insurance Program (NFIP) aimed to increase community awareness of flood risk and encourage risk This guide is intended to help you and your students understand the importance of the High Water Mark Initiative and provide you with mitigation actions. The classroom tools you can use to teach your students what to do before, HWM Initiative uses signs during, and after major storms, why storm surge and floods happen, and on public and private what can be done to prevent or lessen storm impacts in the future. property to show the high water mark from past flooding events like FLASH FLOODS are the #1 Weather Related Killer in the US! Hurricane Irene in 2011 or Our hope is that this guide will increase your confidence in teaching about Superstorm Sandy in 2012. flood risk so students and their families will be well-informed before future For more information events. The lessons and activities included in this guide could be integrated about Monmouth County’s into your science lessons on weather, climate, or human impact on the earth, HWM Initiative go to: or during social studies lessons on geography or people and the environment.