Afghanistan Strategy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Afghan National Security Forces Getting Bigger, Stronger, Better Prepared -- Every Day!

afghan National security forces Getting bigger, stronger, better prepared -- every day! n NATO reaffirms Afghan commitment n ANSF, ISAF defeat IEDs together n PRT Meymaneh in action n ISAF Docs provide for long-term care In this month’s Mirror July 2007 4 NATO & HQ ISAF ANA soldiers in training. n NATO reaffirms commitment Cover Photo by Sgt. Ruud Mol n Conference concludes ANSF ready to 5 Commemorations react ........... turn to page 8. n Marking D-Day and more 6 RC-West n DCOM Stability visits Farah 11 ANA ops 7 Chaghcharan n ANP scores victory in Ghazni n Gen. Satta visits PRT n ANP repels attack on town 8 ANA ready n 12 RC-Capital Camp Zafar prepares troops n Sharing cultures 9 Security shura n MEDEVAC ex, celebrations n Women’s roundtable in Farah 13 RC-North 10 ANSF focus n Meymaneh donates blood n ANSF, ISAF train for IEDs n New CC for PRT Raising the cup Macedonian mid fielder Goran Boleski kisses the cup after his team won HQ ISAF’s football final. An elated team-mate and team captain Elvis Todorvski looks on. Photo by Sgt. Ruud Mol For more on the championship ..... turn to page 22. 2 ISAF MIRROR July 2007 Contents 14 RC-South n NAMSA improves life at KAF The ISAF Mirror is a HQ ISAF Public Information product. Articles, where possible, have been kept in their origi- 15 RAF aids nomads nal form. Opinions expressed are those of the writers and do not necessarily n Humanitarian help for Kuchis reflect official NATO, JFC HQ Brunssum or ISAF policy. -

Traces Volume 30, Number 4 Kentucky Library Research Collections Western Kentucky University, [email protected]

Western Kentucky University TopSCHOLAR® Traces, the Southern Central Kentucky, Barren Kentucky Library - Serials County Genealogical Newsletter Winter 2002 Traces Volume 30, Number 4 Kentucky Library Research Collections Western Kentucky University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wku.edu/traces_bcgsn Part of the Genealogy Commons, Public History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Kentucky Library Research Collections, "Traces Volume 30, Number 4" (2002). Traces, the Southern Central Kentucky, Barren County Genealogical Newsletter. Paper 121. https://digitalcommons.wku.edu/traces_bcgsn/121 This Newsletter is brought to you for free and open access by TopSCHOLAR®. It has been accepted for inclusion in Traces, the Southern Central Kentucky, Barren County Genealogical Newsletter by an authorized administrator of TopSCHOLAR®. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ISSN - 0882-2158 2002 VOLUME 30 ISSUE NO. 4 WINTER TR?iCES i -if •i i i FIRST PRESBYTERIAN CHURCH GLASGOW, KENTUCKY Quarterly Publication of THE SOUTH CENTRAL KENTUCKY HISTORICAL AND GENEALOGICAL SOCIETY, INCORPORATED P.O. Box 157 Glasgow, Kentucky 42142-0157 SOUTH CENTRAL KENTUCKY HISTORTrAT AND GENEALOGICAL SOCIETY Post Office Box 157 Glasgow, KY 42142-0157 OFFICERS AND DIRECTORS 2001-2002 PRESIDENT Joe DoDald Taylor l^'^VICE PRESIDENT Vacant 2"'* VICE PRESIDENT Kenneth Beard, Membenhiip 3'" VICE PRESIDENT Brice T. Leech RECORDING SECRETARY Gayle Berry CORRESPONDING SECRETARY/ TREASLHER Juanita Bardin ASSISTANT TREASURER Ruth Wood "TRACES" EDITOR Sandi Gorin BOARD OF DIRECTORS Hack Bertram Mary Ed Chamberlain Clorine Lawson Don Novosel Ann Rogers PAST PRESTDENTS Paul Bastien L. E. Calhoun Cecil Goode Kay Harbison Jerry Houchens Brice T. Leech John Mutter James Simmons * Katie M. -

Tell Me How This Ends Military Advice, Strategic Goals, and the “Forever War” in Afghanistan

JULY 2019 Tell Me How This Ends Military Advice, Strategic Goals, and the “Forever War” in Afghanistan AUTHOR Mark F. Cancian A Report of the CSIS INTERNATIONAL SECURITY PROGRAM JULY 2019 Tell Me How This Ends Military Advice, Strategic Goals, and the “Forever War” in Afghanistan AUTHOR Mark F. Cancian A Report of the CSIS International Security Program Lanham • Boulder • New York • London About CSIS Established in Washington, D.C., over 50 years ago, the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS) is a bipartisan, nonprofit policy research organization dedicated to providing strategic in sights and policy solutions to help decisionmakers chart a course toward a better world. In late 2015, Thomas J. Pritzker was named chairman of the CSIS Board of Trustees. Mr. Pritzker succeeded former U.S. senator Sam Nunn (D-GA), who chaired the CSIS Board of Trustees from 1999 to 2015. CSIS is led by John J. Hamre, who has served as president and chief executive officer since 2000. Founded in 1962 by David M. Abshire and Admiral Arleigh Burke, CSIS is one of the world’s preeminent international policy in stitutions focused on defense and security; regional study; and transnational challenges ranging from energy and trade to global development and economic integration. For eight consecutive years, CSIS has been named the world’s number one think tank for defense and national security by the University of Pennsylvania’s “Go To Think Tank Index.” The Center’s over 220 full-time staff and large network of affiliated scholars conduct research and analysis and develop policy initiatives that look to the future and anticipate change. -

Principles of Counterinsurgency Garner the Support of Enough of the Population the Principles and Imperatives of Modern Coun to Create Stability

Eliot Cohen; Lieutenant Colonel Conrad Crane, U.S. Army, Retired; Lieutenant Colonel Jan Horvath, U.S. Army; and Lieutenant Colonel John Nagl, U.S. Army MERICA began the 20th century with helps illuminate the extraordinary challenges inher Amilitary forces engaged in counterinsurgency ent in defeating an insurgency. (COIN) operations in the Philippines. Today, it is Legitimacy as the main objective. A legitimate conducting similar operations in Afghanistan, Iraq, government derives its just powers from the gov and a number of other countries around the globe. erned and competently manages collective security During the past century, Soldiers and Marines and political, economic, and social development. gained considerable experience fighting insurgents Legitimate governments are inherently stable. They in Southeast Asia, Latin America, Africa, and now engender the popular support required to manage in Southwest Asia and the Middle East. internal problems, change, and conflict. Illegitimate Conducting a successful counterinsurgency governments are inherently unstable. Misguided, requires an adaptive force led by agile leaders. corrupt, and incompetent governance inevitably While every insurgency is different because of fosters instability. Thus, illegitimate governance is distinct environments, root causes, and cultures, all the root cause of and the central strategic problem successful COIN campaigns are based on common in today’s unstable globalsecurity environment. principles. All insurgencies use variations of stand Five actions that are indicators of legitimacy and ard frameworks and doctrine and generally adhere that any political actor facing threats to stability to elements of a definable revolutionary campaign should implement are— plan. In the Information Age, insurgencies have ● Free, fair, and frequent selection of leaders. -

Afghanistan 2015 Human Rights Report

AFGHANISTAN 2015 HUMAN RIGHTS REPORT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Afghanistan is an Islamic republic with a strong, directly elected presidency, a bicameral legislative branch, and a judicial branch. Presidential and provincial elections held in 2014 were marred by allegations of fraud that led to an audit of all ballot boxes. Protracted political negotiations between the presidential candidates led to the creation of a national unity government headed by President Ashraf Ghani, with runner-up Abdullah Abdullah assuming the newly created post of chief executive officer. Constitutionally mandated parliamentary elections did not take place during the year. The most recent parliamentary elections took place in 2010 and were marred by high levels of fraud and violence, according to domestic observers, the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe, and other international election-monitoring organizations. Civilian authorities generally maintained control over the security forces, although there were occasions when security forces acted independently. The most significant human rights problems were widespread violence, including indiscriminate attacks on civilians by armed insurgent groups; armed insurgent groups’ killings of persons affiliated with the government; torture and abuse of detainees by government forces; widespread disregard for the rule of law and little accountability for those who committed human rights abuses; and targeted violence of and endemic societal discrimination against women and girls. Other human rights problems included -

The Afghanistan-Pakistan Wars, 2008–2009: Micro-Geographies, Conflict Diffusion, and Clusters of Violence

The Afghanistan-Pakistan Wars, 2008–2009: Micro-geographies, Conflict Diffusion, and Clusters of Violence John O’Loughlin, Frank D. W. Witmer, and Andrew M. Linke1 Abstract: A team of political geographers analyzes over 5,000 violent events collected from media reports for the Afghanistan and Pakistan conflicts during 2008 and 2009. The violent events are geocoded to precise locations and the authors employ an exploratory spatial data analysis approach to examine the recent dynamics of the wars. By mapping the violence and examining its temporal dimensions, the authors explain its diffusion from traditional foci along the border between the two countries. While violence is still overwhelmingly concentrated in the Pashtun regions in both countries, recent policy shifts by the American and Pakistani gov- ernments in the conduct of the war are reflected in a sizeable increase in overall violence and its geographic spread to key cities. The authors identify and map the clusters (hotspots) of con- flict where the violence is significantly higher than expected and examine their shifts over the two-year period. Special attention is paid to the targeting strategy of drone missile strikes and the increase in their number and geographic extent by the Obama administration. Journal of Economic Literature, Classification Numbers: H560, H770, O180. 15 figures, 1 table, 113 ref- erences. Key words: Afghanistan, Pakistan, Taliban, Al- Qaeda, insurgency, Islamic terrorism, U.S. military, International Security Assistance Forces, Durand Line, Tribal Areas, Northwest Frontier Province, ACLED, NATO. merica’s “longest war” is now (August 2010) nearing its ninth anniversary. It was Alaunched in October 2001 as a “war of necessity” (Barack Obama, August 17, 2009) to remove the Taliban from power in Afghanistan, and thus remove the support of this regime for Al-Qaeda, the terrorist organization that carried out the September 2001 attacks in the United States. -

Institutional Memory and the US Air Force Lt Col Daniel J

Institutional Memory and the US Air Force Lt Col Daniel J. Brown, USAF Disclaimer: The views and opinions expressed or implied in theJournal are those of the authors and should not be construed as carrying the official sanction of the Department of Defense, Air Force, Air Education and Training Command, Air University, or other agencies or departments of the US government. This article may be reproduced in whole or in part without permission. If it is reproduced, theAir and Space Power Journal requests a courtesy line. No modern war has been won without air superiority. —Gen T. Michael Moseley, 2007 lthough the vague term modern war leaves some question about the wars General Moseley was referring to, his 2007 white paper raises questions re- garding airpower’s impact and historical record, especially in light of the two Aconflicts that consumed the US military at the end of that year.1 The question of whether or not air superiority is vital to successful military operations is nothing new; indeed, arguments concerning the utility of American airpower have raged in earnest for over 100 years. No technological milestone such as the atomic bomb, super- sonic flight, precision-guided weapons, or even stealth has settled the debate about where Airmen and airpower fit in the dialogue of national defense. After each ad- vance is tested in combat, a new round of intellectual sparring commences regarding 38 | Air & Space Power Journal Institutional Memory and the US Air Force the effect of airpower. Though hugely useful in the development of military think- ing, these differing schools of thought have always returned to fundamental ques- tions, the answers to which vary widely depending on the strategic context of the day. -

Battlefields and Boardrooms: Women's Leadership in the Military and Private Sector

Battlefields and Boardrooms JANUARY 2015 Women’s Leadership in the Military and the Private Sector By Nora Bensahel, David Barno, Katherine Kidder, and Kelley Sayler Acknowledgements The authors would like to thank the many people who contributed their time and energy to help bring this report to publication. We would like to thank our CNAS colleagues senior fellow Phil Carter and research intern Sam Arras for their important contributions throughout the development of the report. We thank Dafna Rand for managing this report’s publication and for her substantive editorial comments. We thank all of our other CNAS colleagues who provided valuable feedback on draft versions of the report. Outside of CNAS, we thank Lewis Runnion and Bank of America for their gener- ous support for this project. We thank the organizers and sponsors of the Cornell University Women Veterans Roundtable, the U.S. armed forces, and several Fortune 500 companies for generously sharing their expertise, insights, and people for interviews. We particularly thank the current and former executive level women leaders we interviewed for this report. We also thank the dozens of dedicated professionals from the U.S. Army, Navy, Air Force, and Marines, active and retired, who shared their insights and perspectives. We offer a special thanks to Liz Fontaine for her creative layout design. The authors alone are responsible for any error of fact, analysis, or omission. Cover Image U.S. Army Spc. Rebecca Buck, a medic from Headquarters and Headquarters Company, 1st Battalion, 14th Infantry Regiment, 2nd Stryker Brigade Combat Team, 25th Infantry Division, provides perimeter security outside an Iraqi police station in the Tarmiya Province of Iraq, March 30, 2008. -

Conflict and Peacebuilding Observatory Nº 35 – November 2015

Conflict and Peacebuilding Observatory Nº 35 – November 2015 WORSENING AFGHANISTAN: As the conflict rages, the Taliban split and Islamic State acquires new prominence US military sources announced the dismantling of what was probably al-Qaeda’s largest training camp. Located in the district of Shorabak in Kandahar province, the camp covered 77.7 km2. Losses of territory to the Taliban in some districts have been offset by gains in others. In Helmand, an offensive lasting several months pitted Afghan forces against the Taliban for control of the districts of Marjah and Nad-e-Ali, where over 200 Taliban and 85 soldiers were killed, according to the provincial government. In Kunduz, Afghan forces recovered a base in the district of Dasht-e-Archi, but lost a district in the province of Badakhshan. Government forces confirmed that alongside the Taliban, over 1,300 foreign insurgents (Pakistanis, Tajiks, Uyghurs and others) participated in the battle of Kunduz. Furthermore, in Nangarhar, where there is a group loyal to Islamic State, over 30 insurgents were killed in drone strikes. The local provincial government has stated that around 200 university students there are linked to Islamist groups. In fact, Islamic State banners were waved during an anti-government demonstration. In Zabul, Islamic State executed seven members of the Hazara (Shia) ethnic group that it abducted in September. Among them were three women, the first to be victims of beheading. Their families carried their bodies to Kabul, where they were joined by thousands of people (20,000 according to some media outlets) in one of the largest protests ever seen in the capital. -

Left in the Dark

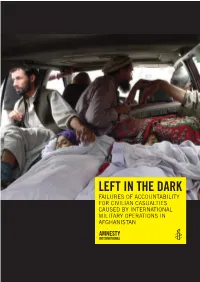

LEFT IN THE DARK FAILURES OF ACCOUNTABILITY FOR CIVILIAN CASUALTIES CAUSED BY INTERNATIONAL MILITARY OPERATIONS IN AFGHANISTAN Amnesty International is a global movement of more than 3 million supporters, members and activists in more than 150 countries and territories who campaign to end grave abuses of human rights. Our vision is for every person to enjoy all the rights enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and other international human rights standards. We are independent of any government, political ideology, economic interest or religion and are funded mainly by our membership and public donations. First published in 2014 by Amnesty International Ltd Peter Benenson House 1 Easton Street London WC1X 0DW United Kingdom © Amnesty International 2014 Index: ASA 11/006/2014 Original language: English Printed by Amnesty International, International Secretariat, United Kingdom All rights reserved. This publication is copyright, but may be reproduced by any method without fee for advocacy, campaigning and teaching purposes, but not for resale. The copyright holders request that all such use be registered with them for impact assessment purposes. For copying in any other circumstances, or for reuse in other publications, or for translation or adaptation, prior written permission must be obtained from the publishers, and a fee may be payable. To request permission, or for any other inquiries, please contact [email protected] Cover photo: Bodies of women who were killed in a September 2012 US airstrike are brought to a hospital in the Alingar district of Laghman province. © ASSOCIATED PRESS/Khalid Khan amnesty.org CONTENTS MAP OF AFGHANISTAN .......................................................................................... 6 1. SUMMARY ......................................................................................................... 7 Methodology .......................................................................................................... -

The Philippines Digital Project

Deep Blue Deep Blue https://deepblue.lib.umich.edu/documents Research Collections Library (University of Michigan Library) 2015 The Philippines Digital Project Scott, Blair https://hdl.handle.net/2027.42/113203 Downloaded from Deep Blue, University of Michigan's institutional repository Logistics of Project ● Questions/concerns about collections/archives to ask ○ Nature of source: Who is the author? What are they discussing? Is it primarily political, economic, or military history? How was this source acquired? Language? Date? etc. ○ Logistics: Was the institution or person affiliated helpful in finding this document? Is it easily accessible? Is it digitized? How did they find it/collect the document? Do they recommend any other collections/historical societies/archives? ● Website design ideas ○ Intended audience: Faculty/scholars, graduate students, undergraduate students (or enthusiasts) interested in Philippine history or conducting research on Philippine history under the American period ○ Goal: to provide an easily accessible, userfriendly web layout for such individuals to find Philippine sources in the state of Michigan (and other states mentioned in the work plan and learning objectives). Lessstudied/underutilized sources will be highlighted in the research guide to make it easier for such individuals to conduct research. ○ Ideas: ■ Some sort of map layout → state by state basis, zoom in and out feature, ability to use tags to find relevant docs. (ex. “women’s history”, “1950’s”, “U.S.Philippine relations”), basic map with list of states underneath (more userfriendly) ■ Simple list feature with tabs → Sort by state, then location/collection, then documents, sort of time period and topic of history ■ Complications could involve whether or not to include previews of docs. -

Cooperation Among Adversaries. Regionalism in the Middle East

Cooperation among adversaries. Regionalism in the Middle East. Master (M.A) in Advanced European and International Studies Trilingual Branch. Academic year 2009/10 Author: Supervisors: Katarzyna Krókowska Dagmar Röttsches – Dubois Matthias Wächter 1 Cooperation among adversaries. Regionalism in the Middle East. Katarzyna Krókowska Master (M.A) in Advanced European and International Studies Centre International de Formation Européenne Institut Européen des Hautes Études Internationales Trilingual Branch. Academic year 2009/10 Table of Contents Introduction .................................................................................................................... 3 Structure of the thesis ........................................................................................................... 7 Understanding and explaining regional cooperation .................................................. 8 Chapter 1: International Relations theory: approaches to understanding regional cooperation .................................................................................................. 11 Realism ............................................................................................................................................................ 12 Transactionalism ........................................................................................................................................ 15 Game Theory ................................................................................................................................................