Post-Election Challenges for the New Government in Kabul

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Afghan National Security Forces Getting Bigger, Stronger, Better Prepared -- Every Day!

afghan National security forces Getting bigger, stronger, better prepared -- every day! n NATO reaffirms Afghan commitment n ANSF, ISAF defeat IEDs together n PRT Meymaneh in action n ISAF Docs provide for long-term care In this month’s Mirror July 2007 4 NATO & HQ ISAF ANA soldiers in training. n NATO reaffirms commitment Cover Photo by Sgt. Ruud Mol n Conference concludes ANSF ready to 5 Commemorations react ........... turn to page 8. n Marking D-Day and more 6 RC-West n DCOM Stability visits Farah 11 ANA ops 7 Chaghcharan n ANP scores victory in Ghazni n Gen. Satta visits PRT n ANP repels attack on town 8 ANA ready n 12 RC-Capital Camp Zafar prepares troops n Sharing cultures 9 Security shura n MEDEVAC ex, celebrations n Women’s roundtable in Farah 13 RC-North 10 ANSF focus n Meymaneh donates blood n ANSF, ISAF train for IEDs n New CC for PRT Raising the cup Macedonian mid fielder Goran Boleski kisses the cup after his team won HQ ISAF’s football final. An elated team-mate and team captain Elvis Todorvski looks on. Photo by Sgt. Ruud Mol For more on the championship ..... turn to page 22. 2 ISAF MIRROR July 2007 Contents 14 RC-South n NAMSA improves life at KAF The ISAF Mirror is a HQ ISAF Public Information product. Articles, where possible, have been kept in their origi- 15 RAF aids nomads nal form. Opinions expressed are those of the writers and do not necessarily n Humanitarian help for Kuchis reflect official NATO, JFC HQ Brunssum or ISAF policy. -

The Afghanistan-Pakistan Wars, 2008–2009: Micro-Geographies, Conflict Diffusion, and Clusters of Violence

The Afghanistan-Pakistan Wars, 2008–2009: Micro-geographies, Conflict Diffusion, and Clusters of Violence John O’Loughlin, Frank D. W. Witmer, and Andrew M. Linke1 Abstract: A team of political geographers analyzes over 5,000 violent events collected from media reports for the Afghanistan and Pakistan conflicts during 2008 and 2009. The violent events are geocoded to precise locations and the authors employ an exploratory spatial data analysis approach to examine the recent dynamics of the wars. By mapping the violence and examining its temporal dimensions, the authors explain its diffusion from traditional foci along the border between the two countries. While violence is still overwhelmingly concentrated in the Pashtun regions in both countries, recent policy shifts by the American and Pakistani gov- ernments in the conduct of the war are reflected in a sizeable increase in overall violence and its geographic spread to key cities. The authors identify and map the clusters (hotspots) of con- flict where the violence is significantly higher than expected and examine their shifts over the two-year period. Special attention is paid to the targeting strategy of drone missile strikes and the increase in their number and geographic extent by the Obama administration. Journal of Economic Literature, Classification Numbers: H560, H770, O180. 15 figures, 1 table, 113 ref- erences. Key words: Afghanistan, Pakistan, Taliban, Al- Qaeda, insurgency, Islamic terrorism, U.S. military, International Security Assistance Forces, Durand Line, Tribal Areas, Northwest Frontier Province, ACLED, NATO. merica’s “longest war” is now (August 2010) nearing its ninth anniversary. It was Alaunched in October 2001 as a “war of necessity” (Barack Obama, August 17, 2009) to remove the Taliban from power in Afghanistan, and thus remove the support of this regime for Al-Qaeda, the terrorist organization that carried out the September 2001 attacks in the United States. -

Migrationsverkets Novemberprognos 2014

Verksamhets- och kostnadsprognos November 2014 1 SVENSKT MEDBORGARSKAP Prognos Diarienummer Planering och styrning 2014‐11‐04 Dnr 1.1.3‐2014‐5644 Till Justitiedepartementet Verksamhets‐ och kostnadsprognos 2014‐11‐04 Migrationsverket ska redovisa anslagsprognoser för 2014–2018 vid fem tillfällen under året. Prognoserna lämnas i Hermes enligt instruktion från Ekonomistyrningsverket. Vid fyra tillfällen ska prognoserna kommenteras både i förhållande till föregående prognostillfälle och i förhållande till budgeten. Prognosen ska innehålla en analys av vilken verksamhet som kan bedrivas med tillgängliga medel och eventuella skillnader mellan tillgängliga medel och behov av medel ska förklaras. Migrationsverket ska lämna nödvändig information till och inhämta nödvändig information från samtliga berörda myndigheter för att kunna presentera en samlad analys. Prognoskommentarerna lämnas till Justitiedepartementet: Prognos 2 (P2‐14) 4 februari Prognos 3 (P3‐14) 24 april Prognos 4 (P4‐14) 24 juli Prognos 5 (P5‐14) 23 oktober 4 november Enligt regeringsbeslut den 16/10 flyttades tidpunkten för när myndigheterna ska lämna den sista prognosen för året till den 4 november 2014. Migrationsverkets prognos 2014‐11‐04 (P5‐14) 1(63) Innehållsförteckning. 1. Övergripande analys och slutsatser .............................................................................. 2 2. Migrationen till Sverige under prognosperioden ........................................................... 6 2.1 Prognos nya asylsökande 2014‐2015 ......................................................................................... -

Suicide Attacks in Afghanistan: Why Now?

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Political Science Department -- Theses, Dissertations, and Student Scholarship Political Science, Department of Spring 5-2013 SUICIDE ATTACKS IN AFGHANISTAN: WHY NOW? Ghulam Farooq Mujaddidi University of Nebraska-Lincoln Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/poliscitheses Part of the Comparative Politics Commons, and the International Relations Commons Mujaddidi, Ghulam Farooq, "SUICIDE ATTACKS IN AFGHANISTAN: WHY NOW?" (2013). Political Science Department -- Theses, Dissertations, and Student Scholarship. 25. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/poliscitheses/25 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Political Science, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Political Science Department -- Theses, Dissertations, and Student Scholarship by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. SUICIDE ATTACKS IN AFGHANISTAN: WHY NOW? by Ghulam Farooq Mujaddidi A THESIS Presented to the Faculty of The Graduate College at the University of Nebraska In Partial Fulfillment of Requirements For the Degree of Master of Arts Major: Political Science Under the Supervision of Professor Patrice C. McMahon Lincoln, Nebraska May, 2013 SUICIDE ATTACKS IN AFGHANISTAN: WHY NOW? Ghulam Farooq Mujaddidi, M.A. University of Nebraska, 2013 Adviser: Patrice C. McMahon Why, contrary to their predecessors, did the Taliban resort to use of suicide attacks in the 2000s in Afghanistan? By drawing from terrorist innovation literature and Michael Horowitz’s adoption capacity theory—a theory of diffusion of military innovation—the author argues that suicide attacks in Afghanistan is better understood as an innovation or emulation of a new technique to retaliate in asymmetric warfare when insurgents face arms embargo, military pressure, and have direct links to external terrorist groups. -

Air War Afghanistan: NATO Air Operations from 2001 Free

FREE AIR WAR AFGHANISTAN: NATO AIR OPERATIONS FROM 2001 PDF Tim Ripley | 272 pages | 19 Mar 2011 | Pen & Sword Books Ltd | 9781848843561 | English | South Yorkshire, United Kingdom List of military operations in the war in Afghanistan (–present) - Wikipedia If you would like us to send you an email whenever we add new stock please enter your email address below. New customer? Create your account. Lost password? Recover password. Remembered your password? Back to login. Already have an account? Login here. Your payment information is processed Air War Afghanistan: NATO Air Operations from 2001. We do not store credit card details nor have access to your credit card information. We have a day return policy, which means you have 30 days after receiving your item to request a return. To be eligible for a return, your item must be in the same condition that you received it, unworn or unused, with tags, and in its original packaging. To start a return, you can contact us at Armyoutfitters rogers. Items sent back to us without first requesting a return will not be accepted. You can always contact us for any return question at Armyoutfitters rogers. Damages and issues Please inspect your order upon reception and contact us immediately if the item is defective, damaged or if you receive the wrong item, so that we can evaluate the issue and make it right. We also do not accept returns for hazardous materials, flammable liquids, or gases. Please get in touch if you have questions or concerns about your specific item. Unfortunately, we cannot accept returns on sale items or gift cards. -

Canada in Afghanistan: 2001-2010 a Military Chronology

Canada in Afghanistan: 2001-2010 A Military Chronology Nancy Teeple Royal Military College of Canada DRDC CORA CR 2010-282 December 2010 Defence R&D Canada Centre for Operational Research & Analysis Strategic Analysis Section Canada in Afghanistan: 2001 to 2010 A Military Chronology Prepared By: Nancy Teeple Royal Military College of Canada P.O. Box 17000 Stn Forces Kingston Ontario K7K 7B4 Royal Military College of Canada Contract Project Manager: Mr. Neil Chuka, (613) 998-2332 PWGSC Contract Number: Service-Level Agreement with RMC CSA: Mr. Neil Chuka, Defence Scientist, (613) 998-2332 The scientific or technical validity of this Contract Report is entirely the responsibility of the Contractor and the contents do not necessarily have the approval or endorsement of Defence R&D Canada. Defence R&D Canada – CORA Contract Report DRDC CORA CR 2010-282 December 2010 Principal Author Original signed by Nancy Teeple Nancy Teeple Approved by Original signed by Stephane Lefebvre Stephane Lefebvre Section Head Strategic Analysis Approved for release by Original signed by Paul Comeau Paul Comeau Chief Scientist This work was conducted as part of Applied Research Project 12qr "Influence Activities Capability Assessment". Defence R&D Canada – Centre for Operational Research and Analysis (CORA) © Her Majesty the Queen in Right of Canada, as represented by the Minister of National Defence, 2010 © Sa Majesté la Reine (en droit du Canada), telle que représentée par le ministre de la Défense nationale, 2010 Abstract …….. The following is a chronology of political and military events relating to Canada’s military involvement in Afghanistan between September 2001 and March 2010. -

Locals Flee As Taliban Nears Key Southern Afghan City

افغانستان آزاد – آزاد افغانستان AA-AA چو کشور نباشـد تن من مبـــــــاد بدین بوم وبر زنده یک تن مــــباد همه سر به سر تن به کشتن دهیم از آن به که کشور به دشمن دهیم www.afgazad.com [email protected] زبان های اروپائی European Languages http://news.antiwar.com/2015/10/20/locals-flee-as-taliban-nears-key-southern-afghan-city/print/ Locals Flee as Taliban Nears Key Southern Afghan City By Jason Ditz October 20, 2015 Afghan Taliban forces have been racking up gains in the southeast, near Ghazni, and still hold some territory in Kunduz Province, though they’ve since left the city of Kunduz itself. Their latest gains are in the important Helmand Province, a key part of the Afghan opium industry, where forces are nearing the capital of Lashkar Gah. Officials say they’ve seen reports of civilians fleeing the city in large numbers, and Taliban gains in Gereshk District have convinced many that the fall of the capital is only a matter of time. The fall of Lashkar Gah would put the Taliban under control of another part of the key Highway 1, this time the part that links Kandahar to the western city of Herat. The Ghazni offensive likewise would effectively give the Taliban control of the highway on the other side of Kandahar, leading to the capital of Kabul. www.afgazad.com 1 [email protected] A nation with little infrastructure, Highway 1 is one of only a few paved roads of import in Afghanistan, and circles around the country, hitting most of the major cities. -

Exploring Long-Term Effectiveness of Armed Drone Strikes in Overseas Contingency Operations

LETHAL TARGETING ABROAD: EXPLORING LONG-TERM EFFECTIVENESS OF ARMED DRONE STRIKES IN OVERSEAS CONTINGENCY OPERATIONS A Thesis submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Georgetown University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Security Studies By Luke A. Olney Washington, DC April 14, 2011 Copyright 2011 by Luke A. Olney All Rights Reserved ii LETHAL TARGETING ABROAD: EXPLORING LONG-TERM EFFECTIVENESS OF ARMED DRONE STRIKES IN OVERSEAS CONTINGENCY OPERATIONS Luke A. Olney, B.A. Thesis Advisor: Adam R. Grissom, Ph.D. ABSTRACT As the U.S.-led war in Afghanistan continues in its tenth year, it is important to evaluate not only the short-term effectiveness, but also the long-term implications of lethal targeting – specifically the use of armed drone strikes – against high-value individuals. This paper explores the following research question: are drone strikes an effective long-term strategy in overseas contingency operations? Specifically, it examines the hypothesis that U.S. drone strikes cause an increased number of militant attacks on local governments, which is likely to contribute to local instability in the long term. Two cases are analyzed to determine the impact of drone strikes on host governments. The first case examines Yemen from January 2001 through September 2010. Data is evaluated on the drone strike that killed Abu Ali al-Harithi on November 3, 2002, and the U.S. cruise missile strikes on targets in Yemen on December 17, 2009, to determine the relationship between U.S. strikes and militant attacks on the Government of Yemen. -

Civilian Casualties During 2007

UNITED NATIONS UNITED NATIONS ASSISTANCE MISSION IN AFGHANISTAN UNAMA CIVILIAN CASUALTIES DURING 2007 Introduction: The figures contained in this document are the result of reports received and investigations carried out by UNAMA, principally the Human Rights Unit, during 2007 and pursuant to OHCHR’s monitoring mandate. Although UNAMA’s invstigations pursue reliability through the use of generally accepted procedures carried out with fairness and impartiality, the full accuracy of the data and the reliability of the secondary sources consulted cannot be fully guaranteed. In certain cases, and due to security constraints, a full verification of the facts is still pending. Definition of terms: For the purpose of this report the following terms are used: “Pro-Governmental forces ” includes ISAF, OEF, ANSF (including the Afghan National Army, the Afghan National Police and the National Security Directorate) and the official close protection details of officials of the IRoA. “Anti government elements ” includes Taliban forces and other anti-government elements. “Other causes ” includes killings due to unverified perpetrators, unexploded ordnances and other accounts related to the conflict (including border clashes). “Civilian”: A civilian is any person who is not an active member of the military, the police, or a belligerent group. Members of the NSD or ANP are not considered as civilians. Grand total of civilian casualties for the overall period: The grand total of civilian casualties is 1523 of which: • 700 by Anti government elements. • -

The Soviet-Afghan War MODERN WAR STUDIES

The Soviet-Afghan War MODERN WAR STUDIES Theodore A. Wilson General Editor Raymond A. Callahan J. Garry Clifford Jacob W. Kipp Jay Luvaas Allan R. Millett Carol Reardon Dennis Showalter Series Editors The Soviet-Afghan War How a Superpower Fought and Lost The Russian General Staff Translated and edited by Lester W. Grau and Michael A. Cress Foreword by Theodore C. Mataxis University Press of Kansas The Russian General Staff authors' collective is headed by Colonel Professor Valentin Runov, candidate of history. Members of the authors' collective include P. D. Alexseyev, Yu. G. Avdeev, Yu. P. Babich, A. M. Fufaev, B. P. Gruzdev, V. S. Kozlov, V. I. Litvinnenko, N. S. Nakonechnyy, V. K. Puzel', S. S. Sharov, S. F. Tsybenko, V. M. Varushinin, P. F. Vazhenko, V. F. Yashin, and V. V. Zakharov. © 2002 by the University Press of Kansas All rights reserved Published by the University Press of Kansas (Lawrence, Kansas 66049), which was or- ganized by the Kansas Board of Regents and is operated and funded by Emporia State Uni- versity, Fort Hays State University, Kansas State University, Pittsburg State University, the University of Kansas, and Wichita State University. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data The Soviet-Afghan War : how a superpower fought and lost: the Russian General Staff / translated and edited by Lester W. Grau and Michael A. Gress ; foreword by Theodore C. Mataxis. p. cm. — (Modern war studies) Translated from Russian. Includes index. ISBN 0-7006-1185-1 (cloth : alk. paper) — ISBN 0-7006-1186-X (paper : alk. paper) 1. Afghanistan—History—Soviet occupation, 1979-1989. -

Global Terrorism Mid-Year

Counter Terrorist Trends and Analysis www.rsis.edu.sg ISSN 2382-6444 | Volume 8, Issue 7 | July 2016 A JOURNAL OF THE INTERNATIONAL CENTRE FOR POLITICAL VIOLENCE AND TERRORISM RESEARCH Global Terrorism Mid-Year Review 2016 Rohan Gunaratna AQ-IS Rivalry: Battle for Supremacy in India Vikram Rajakumar Revival of Violence in Kashmir: The Threat to India’s Security Akanksha Narain IS in Afghanistan: Emergence, Evolution and Expansion Inomjon Bobokulov Appointment of the New Taliban Chief: Implications for Peace and Conflict in Afghanistan Abdul Basit Is Al Qaeda Central Relocating? Mahfuh Halimi Counter Terrorist Trends and Analysis Volume 8, Issue 7 | July 2016 1 Building a Global Network for Security Editorial Note South Asia & Central Asia Focus As we enter into the second half of 2016, South Asia remains a front line in the battle against terrorism. Regional rivalry for dominance between the Islamic State (IS) and Al Qaeda (AQ) has highlighted the likelihood of an increase in scope and frequency of terrorist attacks across South Asia. The establishment of Al Qaeda in the Indian Subcontinent (AQIS) in September 2014 as well as the Islamic State's Wilayat Khorasan in January 2015 has transformed South Asia into an important focal point for both organisations. As evidence of IS’ focus on South Asia, the group released its latest issue of the English-language magazine, Dabiq, featuring a prominent interview with the purported IS chief in Bangladesh, Abu WIbrahim al -Hanif, speaking on launching a large-scale attack against India. Against the backdrop of the Islamic State (IS)’ increasing inroads into India, the country remained a target of terrorist attacks, including terrorist operations launched by Maoist insurgents and domestic and transnational groups. -

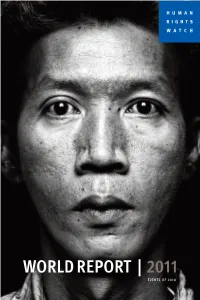

WORLDREPORT Rights to Ensure That the Quest for Cooperation Does Not Become an Excuse for Inaction

HUMAN RIGHTS WATCH WORLD REPOR T | 2011 EVENTS OF 2010 HUMAN RIGHTS WATCH WORLD REPORT 2011 EVENTS OF 2010 Copyright © 2011 Human Rights Watch All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America ISBN-13: 978-1-58322-921-7 Front cover photo: Aung Myo Thein, 42, spent more than six years in prison in Burma for his activism as a student union leader. More than 2,200 political prisoners—including artists, journalists, students, monks, and political activists—remain locked up in Burma's squalid prisons. © 2010 Platon for Human Rights Watch Back cover photo: A child migrant worker from Kyrgyzstan picks tobacco leaves in Kazakhstan. Every year thousands of Kyrgyz migrant workers, often together with their chil- dren, find work in tobacco farming, where many are subjected to abuse and exploitation by employers. © 2009 Moises Saman/Magnum for Human Rights Watch Cover and book design by Rafael Jiménez 350 Fifth Avenue, 34th floor 51 Avenue Blanc, Floor 6, New York, NY 10118-3299 USA 1202 Geneva, Switzerland Tel: +1 212 290 4700 Tel: +41 22 738 0481 Fax: +1 212 736 1300 Fax: +41 22 738 1791 [email protected] [email protected] 1630 Connecticut Avenue, N.W., Suite 500 Poststraße 4-5 Washington, DC 20009 USA 10178 Berlin, Germany Tel: +1 202 612 4321 Tel: +49 30 2593 06-10 Fax: +1 202 612 4333 Fax: +49 30 2593 06-29 [email protected] [email protected] 2-12 Pentonville Road, 2nd Floor 1st fl, Wilds View London N1 9HF, UK Isle of Houghton Tel: +44 20 7713 1995 Boundary Road (at Carse O’Gowrie) Fax: +44 20 7713 1800 Parktown, 2198 South Africa [email protected] Tel: +27-11-484-2640, Fax: +27-11-484-2641 27 Rue de Lisbonne #4A, Meiji University Academy Common bldg.