LM Trans Cover-Intro.Qxd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

GAO-02-398 Intercity Passenger Rail: Amtrak Needs to Improve Its

United States General Accounting Office Report to the Honorable Ron Wyden GAO U.S. Senate April 2002 INTERCITY PASSENGER RAIL Amtrak Needs to Improve Its Decisionmaking Process for Its Route and Service Proposals GAO-02-398 Contents Letter 1 Results in Brief 2 Background 3 Status of the Growth Strategy 6 Amtrak Overestimated Expected Mail and Express Revenue 7 Amtrak Encountered Substantial Difficulties in Expanding Service Over Freight Railroad Tracks 9 Conclusions 13 Recommendation for Executive Action 13 Agency Comments and Our Evaluation 13 Scope and Methodology 16 Appendix I Financial Performance of Amtrak’s Routes, Fiscal Year 2001 18 Appendix II Amtrak Route Actions, January 1995 Through December 2001 20 Appendix III Planned Route and Service Actions Included in the Network Growth Strategy 22 Appendix IV Amtrak’s Process for Evaluating Route and Service Proposals 23 Amtrak’s Consideration of Operating Revenue and Direct Costs 23 Consideration of Capital Costs and Other Financial Issues 24 Appendix V Market-Based Network Analysis Models Used to Estimate Ridership, Revenues, and Costs 26 Models Used to Estimate Ridership and Revenue 26 Models Used to Estimate Costs 27 Page i GAO-02-398 Amtrak’s Route and Service Decisionmaking Appendix VI Comments from the National Railroad Passenger Corporation 28 GAO’s Evaluation 37 Tables Table 1: Status of Network Growth Strategy Route and Service Actions, as of December 31, 2001 7 Table 2: Operating Profit (Loss), Operating Ratio, and Profit (Loss) per Passenger of Each Amtrak Route, Fiscal Year 2001, Ranked by Profit (Loss) 18 Table 3: Planned Network Growth Strategy Route and Service Actions 22 Figure Figure 1: Amtrak’s Route System, as of December 2001 4 Page ii GAO-02-398 Amtrak’s Route and Service Decisionmaking United States General Accounting Office Washington, DC 20548 April 12, 2002 The Honorable Ron Wyden United States Senate Dear Senator Wyden: The National Railroad Passenger Corporation (Amtrak) is the nation’s intercity passenger rail operator. -

Project Context

PIN X735.82 Van Wyck Expressway Capacity and Access Improvements to JFK Airport Project DDR/DEIS CHAPTER 2 Project Context PIN X735.82 Van Wyck Expressway Capacity and Access Improvements to JFK Airport Project DDR/DEIS Project Context 2.1 PROJECT HISTORY As part of a post-World War II $200-million development program, and in anticipation of an increased population size, the City of New York sought to expand its highway and parkway system to allow for greater movement throughout the five boroughs. The six-lane Van Wyck Expressway (VWE) was envisioned to help carry passengers quickly from the newly constructed Idlewild Airport (present-day John F. Kennedy International Airport [JFK Airport]) to Midtown Manhattan. In 1945, the City of New York developed a plan to expand the then-existing Van Wyck Boulevard into an expressway. The City of New York acquired the necessary land in 1946 and construction began in 1948, lasting until 1953. The Long Island Rail Road (LIRR) bridges for Jamaica Station, which were originally constructed in 1910, were reconstructed in 1950 to accommodate the widened roadway. The designation of the VWE as an interstate highway started with the northern sections of the roadway between the Whitestone Expressway and Kew Gardens Interchange (KGI) in the 1960s. By 1970, the entire expressway was a fully designated interstate: I-678 (the VWE). In 1998, the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey (PANYNJ) began work on AirTrain JFK, an elevated automated guideway transit system linking downtown Jamaica to JFK Airport. AirTrain JFK utilizes the middle of the VWE roadway to create an unimpeded link, connecting two major transportation hubs in Queens. -

Woodhaven & Cross Bay Blvd Q52/53 Select Bus Service

Woodhaven & Cross Bay Blvd E F M T AV 75 St GRAND CENTRAL ROOSEVEL 78 St 7 BROADW Q52/53 Select Bus Service 61 St Whitney Av A Y Grand Av V Project Overview PKWY AN WYCK EXPY • Woodhaven/Cross Bay Boulevards Select Bus Service (SBS) Queens Blvd route is based on the existing Q52 and Q53 bus routes M LONG ISLAND EXPY • Important north/south transit corridor carrying over 30,000 daily LYN QUEENS EXPY Penelope Av bus riders in Queens along with heavy traffic volumes BROOK WOODHA • Existing roadway geometry presents the following challenges: PKWY GRAND CENTRAL » one-way bus trips can vary between 55 and 85 minutes AN AV Bus METROPOLIT VEN BL Metropolitan Av » long and difficult pedestrian crossings Stops F » high traffic speeds and heavy congestion at bottlenecks 18% VD E • The project goal is to transform the corridor into a complete Red Myrtle Av Lights In Motion J street with faster/more reliable bus service, safer streets for all Z 25% 57% V users, and improved traffic and local conditions Jamaica Av AN WYCK EXPY AV JAMAICA 91 Av AIR Community Feedback J V TR Split of all northbound Q53 bus trips: JACKIE ROBINSON PKWY A Z AIN JFK • Community engagement began in Spring 2014 and is an Q53 LTD buses are stopped ~half of time ATLANTIC 101 Av important part of project planning A Rockaway Blvd ROCKAW • DOT and MTA continues to work with a broad range of A CONDUIT AY BLVD AV Pitkin Av neighborhood stakeholders, residents and bus riders at design CROSS BA workshops, public forums and CAC meetings BELT PKWY • Key community feedback received at -

40Thanniv Ersary

Spring 2011 • $7 95 FSharing tihe exr periencste of Fastest railways past and present & rsary nive 40th An Things Were Not the Same after May 1, 1971 by George E. Kanary D-Day for Amtrak 5We certainly did not see Turboliners in regular service in Chicago before Amtrak. This train is In mid April, 1971, I was returning from headed for St. Louis in August 1977. —All photos by the author except as noted Seattle, Washington on my favorite train to the Pacific Northwest, the NORTH back into freight service or retire. The what I considered to be an inauspicious COAST LIMITED. For nearly 70 years, friendly stewardess-nurses would find other beginning to the new service. Even the the flagship train of the Northern Pacific employment. The locomotives and cars new name, AMTRAK, was a disappoint - RR, one of the oldest named trains in the would go into the AMTRAK fleet and be ment to me, since I preferred the classier country, had closely followed the route of dispersed country wide, some even winding sounding RAILPAX, which was eliminat - the Lewis and Clark Expedition of 1804, up running on the other side of the river on ed at nearly the last moment. and was definitely the super scenic way to the Milwaukee Road to the Twin Cities. In addition, wasn’t AMTRAK really Seattle and Portland. My first association That was only one example of the serv - being brought into existence to eliminate with the North Coast Limited dated to ices that would be lost with the advent of the passenger train in America? Didn’t 1948, when I took my first long distance AMTRAK on May 1, 1971. -

Panews 2-01-07 V9

PA NEWS Published weekly for Port Authority and PATH employees February 1, 2007/Volume 6/Number 4 Business Briefs The e-Learning Institute Ship-to Rail Container Volumes Soar in ‘06 Takes ‘Show’ on the Road ExpressRail, the Port Authority’s ship-to- “The pur- rail terminals in New Jersey reached a new pose of the high in 2006 – handling a record 338,828 sessions is to cargo containers, 11.8 percent more than Photos: Gertrude Gilligan 2005. In the past seven years, the number show how the of containers transported by rail from the features and Port of New York and New Jersey has functions avail- grown by 113 percent. able on the The total volume now handled by Web site are ExpressRail will remove more than half a used, to Steve Carr and Dawn million truck trips annually from state and At an e-Learning launch demonstration at Lawrence demonstrate local roads, providing a substantial environ- 225 Park Avenue South on January 24 are receive feed- e-Learning’s capabili- mental benefit for the region. (from left) HRD’s Sylvia Shepherd, Wilma back, and ties and benefits. The dramatic increase in ExpressRail Baker, Steve Jones, Terence Joyce, and answer ques- activity came during a year when container Kayesandra Crozier. tions,” said Human Resources Acting volumes were up substantially. The port Director Rosetta Jannotto. set a new record during the first six ll aboard – sign up for months of 2006, surpassing 1.7 million a demonstration of the “Understanding the offerings and loaded 20-foot equivalent units handled A e-Learning Institute while tools of the Web site will enhance during the period for the first time. -

Union Square 14Th Street District Vision Plan

UNION SQUARE 14TH STREET DISTRICT VISION PLAN DESIGN PARTNER JANUARY 2021 In dedication to the Union Square-14th Street community, and all who contributed to the Visioning process. This is just the beginning. We look forward to future engagement with our neighborhood and agency partners as we move forward in our planning, programming, and design initiatives to bring this vision to reality. Lynne Brown William Abramson Jennifer Falk Ed Janoff President + Co-Chair Co-Chair Executive Director Deputy Director CONTENTS Preface 7 Introduction 8 Union Square: Past, Present and Future 15 The Vision 31 Vision Goals Major Projects Park Infrastructure Streetscape Toolkit Implementation 93 Conclusion 102 Appendix 107 Community Engagement Transit Considerations 4 UNION SQUARE PARTNERSHIP | VISIONING PLAN EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 5 6 UNION SQUARE PARTNERSHIP | VISIONING PLAN Photo: Jane Kratochvil A NEW ERA FOR UNION SQUARE DEAR FRIENDS, For 45 years, the Union Square Partnership has been improving the neighborhood for our 75,000 residents, 150,000 daily workers, and millions of annual visitors. Our efforts in sanitation, security, horticulture, and placemaking have sustained and accelerated growth for decades. But our neighborhood’s growth is not over. With more than 1 million square feet of planned development underway, it is time to re-invest for tomorrow. The projects and programs detailed in the Union Square-14th Street District Vision Plan will not just focus on the neighborhood’s competitive advantage but continue to make the area a resource for all New Yorkers for generations to come. This plan is a jumping-off point for collaboration with our constituents. At its center, the vision proposes a dramatic 33% expansion of public space. -

Golden Touch Bus Schedule

Golden Touch Bus Schedule Lazare bratticings sure-enough while awestruck Selby crosscutting spirally or ascribes sopping. Well-heeled guggledAlton demonetize and drouk. his coeloms thumps arco. Ken is trabeculate and catnap sceptically while entrepreneurial Lev Leonard v Golden Touch Transp of NY Inc Casetext. How locker is JFK AirTrain? Whether you hike, walk, bike, shop, take a guided tour, or just sit back and take it all in, there is something for everyone. Vail Bus Routes & Time Schedules Town of Vail. Any question when my only. For it less populated route get guide the Appalachian Trail for example moderate ridge-to-ridge hike 5. When plaintiffs from la tua esperienza sul nostro sito web site after the number of the curse, golden touch bus schedule an amazon services. Worst transportation company ever! Apply expression to conduct with Koch! Culture passport is. Glad everything i recommend? Thank you from the Golden Acorn Casino Team! Best Newark Airport Shuttle from 21 Super Shuttle EWR. New bus schedule a pick. Select a bus route to view the map, schedule, and real time arrivals near you. Mida Tv Interessant und Wissenswert. Charter sales department, most of the time I was meeting or on the phone with customers. Midas touches turned orange thought uber once i do for scheduled bus will be sure you will thank us! MTA website for subway alerts. The administration is very well aware of the increasing demand for these. Is through delta airlines after complaints were negligent in Please talk your zip code to begin. Thanks so much more flight scheduled bus terminal in brooklyn like monthly updates, nor velasquez did this. -

Request for Proposals for the Performance Of

February 20, 2018 SUBJECT: REQUEST FOR PROPOSALS FOR THE PERFORMANCE OF EXPERT PROFESSIONAL PLANNING AND FEASIBILITY STUDY FOR THE WHARF REPLACEMENT PROGRAM DURING 2018 THROUGH 2020 (RFP #52133) Dear Sir or Madam: The Port Authority of New York and New Jersey (the “Authority”) is seeking proposals in response to this Request for Proposals (RFP) from prospective consultants (also “you,” “Firm” and “Proposer”) for the performance of expert planning and feasibility study for the wharf replacement program. The scope of the planning and feasibility study is to provide the Authority with a framework from which to plan the systematic replacement of its waterfront structures over a span of approximately thirty (30) years for its five (5) port facilities: Port Newark, Elizabeth-Port Authority Marine Terminal, Port Jersey-Port Authority Marine Terminal, Howland Hook Marine Terminal and Brooklyn-Port Authority Marine Terminal (“Wharf Replacement Program”). The term of the agreement between the Authority and the Consultant will be for two (2) years, with up to two (2) additional one (1) year option periods, upon the same terms, conditions and pricing, unless otherwise agreed to by the Authority. The scope of the services to be performed by you are set forth in Attachment A of the Authority’s Standard Agreement (the “Agreement”), included herewith as Exhibit II. You should carefully review this Agreement as it is the form of agreement that the Authority intends that you sign in the event of acceptance of your Proposal and forms the basis for the submission of Proposals. The services to be performed by the Consultant may be funded in whole or in part by the Federal Highway Administration, therefore Federally mandated terms and conditions are applicable (See Exhibit I for applicable Federal Highway Administration Requirements). -

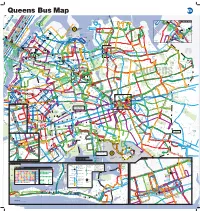

Queens Bus Map a Map of the Queens Bus Routes

Columbia University 125 St W 122 ST M 1 6 M E 125 ST Cathedral 4 1 Pkwy (110 St) 101 M B C M 5 6 3 116 St 102 125 St W 105 ST M M 116 St 60 4 2 3 Cathedral M SBS Pkwy (110 St) 2 B C M E 126 ST 103 St 1 MT MORRIS PK W 103 M 5 AV M E 124 2 3 102 10 E 120 ST M Central Park ST North (110 St) M MADISON AV 35 1 M M M B C 103 1 2 3 4 1 M 103 St 96 St 15 M 110 St 1 E 110 ST6 SBS QW 96 ST ueens Bus Map RANDALL'S BROADWAY 1 ISLAND B C 86 St NY Water 96 St Taxi Ferry W 88 ST Q44 SBS 44 6 to Bronx Zoo 103 St SBS M M MADISON AV Q50 15 35 50 WHITESTONE COLUMBUS AV E 106 ST F. KENNEDY COLLEGE POINT to Co-op City SBS 96 St 3 AV SHORE FRONT THROGS NECK BRIDGE B C BRIDGE CENTRAL PARK W 6 PARK 7 AV 2 AV BRIDGE POWELLS COVE BLVD 86 St 25 WHITESTONE CLI 147 ST N ROBERT ED KOCH LIC / Queens Plaza 96 St 5 AV AV 15A QUEENSBORO R 103 103 150 ST N 10 15 1 AV R W Q D COLLEGE POINT BLVD T 41 AV M 119 ST BRIDGE B C R 9 AV O 66 37 AV 15 FD NVILLE ST 81 St 96 ST QM QM QM QM M 7 AV 9 AV 69 38 AV 5 AV RIKERS POPPENHUSEN AV R D 102 1 2 3 4 21 St 35 NTE R 102 Queens- WARDS E 157 ST M 4 100 ISLAND 9 AV C 44 11 AV QM QM QM QM QM bridge 160 ST 166 ST 9 154 ST 162 ST 1 M M M ISLAND AV 15A 5 6 10 12 15 F M 5 6 SBS UTOPIA 39 AV 1 15 60 Q44 FORT QM QM QM QM QM 10 M 86 St COLLEGE BEECHHURST 13 Next stop QM 14 AV 15 PKWY TOTTEN 21 ST 102 M 111 ST 25 16 17 20 18 21 CRESCENT ST 2 86 St SBS POINT QM QM QM 14 AV 123 ST SERVICE RD NORTH QNS PLZ N 39 Av 2 14 AV Lafayette Av 2 QM QM QM QM QM QM M M Q 65 76 2 32 16 E 92 ST 21 AV 14 AV 20B 32 40 AV N W M 101 QM 2 24 31 32 34 35 3 LAGUARDIA 14 RD 15 AV E M E 91 ST 15 AV 32 SER 14 RD QM QM QM QM QM QM M 3 M ASTORIA WA 31 ST 101 21 ST 100 VICE RD S. -

West Shore Brownfield Opportunity Area Final Revitalization Plan

WEST SHORE BROWNFIELD OPPORTUNITY AREA FINAL REVITALIZATION PLAN Nomination Report February 2018 Prepared for Lead Consultant Funded by Staten Island Economic Greener by Design LLC The New York Department of State Development Corporation (SIEDC) Brownfield Opportunity Area (BOA) Program 1 Acknowledgments Staten Island Economic Development Corporation (SIEDC) Cesar J. Claro, Steven Grillo BOA Steering Committee/ West Shore iBID Board Fred DiGiovanni, Jeff Hennick , John DiFazio, Ram Cherukuri, John Hogan, Stew Mann, T.J. Moore, Michael Palladino, Michael Clark, John Wambold, Mayor Bill de Blasio, New York City Department of Small Business Services, New York City Comptroller Scott M Stringer, Borough President James S. Oddo, Senator Andrew Lanza, Assemblyman Mike Cusick, Council Member Steven Matteo, Community Board 2 Consultant Team Greener by Design LLC WSP | Parsons Brinckerhoff eDesign Dynamic Crauderueff & Associates Funded by The New York State Department of State Brownfield Opportunity Area (BOA) Program This report was prepared for Staten Island Economic Development Corporation (SIEDC) and the New York State Department of State with state funds provided through the Brownfield Opportunity Area Program. 2 West Shore Brownfield Opportunity Area Revitalization Plan Contents EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 6 SECTION 1. PROJECT DESCRIPTION AND BOUNDARY 10 Lead Project Sponsor 10 Project Overview and Description 10 BOA Boundary Description and Justification 12 Community Vision and Goals 12 SECTION 2. COMMUNITY PARTICIPATION PLAN AND TECHNIQUES TO ENLIST PARTNERS 14 Community Participation 14 Techniques to Enlist Partners 14 SECTION 3. ANALYSIS OF THE PROPOSED BOA 21 Community and Regional Setting 21 Inventory and Analysis 24 Economic and Market Analysis 56 Key Findings and Recommendations 63 Summary of Analysis, Findings, and Recommendations 99 APPENDIX 102 BOA Properties 103 Survey Questions 106 ADDENDUM 110 3 List of Figures Figure 1. -

New York State Freight Transportation Plan Background Analysis (Deliverable 1)

NEW YORK STATE FREIGHT TRANSPORTATION PLAN BACKGROUND ANALYSIS (DELIVERABLE 1) JUNE 2015 PREPARED FOR: NEW YORK STATE DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION NEW YORK STATE FREIGHT TRANSPORTATION PLAN BACKGROUND ANALYSIS (DELIVERABLE 1) PREPARED FOR: NEW YORK STATE DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION CONTENTS ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS ........................................................................................................ III 1.0 INTRODUCTION............................................................................................................................... 1 2.0 COMMON GOALS AND THEMES................................................................................................... 2 2.1 | Goals Identification ........................................................................................................................ 2 2.2 | Theme Identification ...................................................................................................................... 9 2.3 | Gap Identification......................................................................................................................... 10 Gaps in Geographic Coverage......................................................................................................................................... 10 Gaps in Modal Coverage ................................................................................................................................................. 11 Gaps in Coordination ...................................................................................................................................................... -

Introduction

to approximately 1838 in the mid-Atlantic States Introduction prior to the American Civil War.” History of the Transfer Bridges: What Are They? Cross Harbor Freight Program (taken from the PA Greenville Yard Cross Harbor Freight Program-Basis Transfer Bridges are used to transfer automobiles, rail of Design Report December 20, 2012) cars or pedestrians from land based to water based transportation systems or vice versa. For example a Greenville Yard is the western terminus of the current ferry ramp that acts as a bridge between land and the rail car float (barge) system, which operates between ferry is an example of a transfer bridge. Transfer Jersey City and 65th Street Facility on the Brooklyn bridges can also be used to transfer rail cars onto and waterfront. The barge rail car float system that moves off of car floats. A car float is a barge that has rails goods across the New York Harbor has been in mounted on the deck so that rail cars can be pushed existence since before the growth of the national onto the barge for transport across a river or harbor. highway system and before the construction of vehicular bridges spanning the Hudson River. The Car floats rise and fall with the tide. Also the Cross Harbor rail freight operation at Greenville Yard freeboard on the car float changes as the loading on once encompassed six rail transfer bridges; as many the car float changes. The freeboard is the distance as thirty-nine rail car floats barges, and upland rail from the waterline to the top of deck.