THE LEGEND of BLOSSOM FALLS While Our Thoughts Are in the Big

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cutting Patterns in DW Griffith's Biographs

Cutting patterns in D.W. Griffith’s Biographs: An experimental statistical study Mike Baxter, 16 Lady Bay Road, West Bridgford, Nottingham, NG2 5BJ, U.K. (e-mail: [email protected]) 1 Introduction A number of recent studies have examined statistical methods for investigating cutting patterns within films, for the purposes of comparing patterns across films and/or for summarising ‘average’ patterns in a body of films. The present paper investigates how different ideas that have been proposed might be combined to identify subsets of similarly constructed films (i.e. exhibiting comparable cutting structures) within a larger body. The ideas explored are illustrated using a sample of 62 D.W Griffith Biograph one-reelers from the years 1909–1913. Yuri Tsivian has suggested that ‘all films are different as far as their SL struc- tures; yet some are less different than others’. Barry Salt, with specific reference to the question of whether or not Griffith’s Biographs ‘have the same large scale variations in their shot lengths along the length of the film’ says the ‘answer to this is quite clearly, no’. This judgment is based on smooths of the data using seventh degree trendlines and the observation that these ‘are nearly all quite different one from another, and too varied to allow any grouping that could be matched against, say, genre’1. While the basis for Salt’s view is clear Tsivian’s apparently oppos- ing position that some films are ‘less different than others’ seems to me to be a reasonably incontestable sentiment. It depends on how much you are prepared to simplify structure by smoothing in order to effect comparisons. -

Papéis Normativos E Práticas Sociais

Agnes Ayres (1898-194): Rodolfo Valentino e Agnes Ayres em “The Sheik” (1921) The Donovan Affair (1929) The Affairs of Anatol (1921) The Rubaiyat of a Scotch Highball Broken Hearted (1929) Cappy Ricks (1921) (1918) Bye, Bye, Buddy (1929) Too Much Speed (1921) Their Godson (1918) Into the Night (1928) The Love Special (1921) Sweets of the Sour (1918) The Lady of Victories (1928) Forbidden Fruit (1921) Coals for the Fire (1918) Eve's Love Letters (1927) The Furnace (1920) Their Anniversary Feast (1918) The Son of the Sheik (1926) Held by the Enemy (1920) A Four Cornered Triangle (1918) Morals for Men (1925) Go and Get It (1920) Seeking an Oversoul (1918) The Awful Truth (1925) The Inner Voice (1920) A Little Ouija Work (1918) Her Market Value (1925) A Modern Salome (1920) The Purple Dress (1918) Tomorrow's Love (1925) The Ghost of a Chance (1919) His Wife's Hero (1917) Worldly Goods (1924) Sacred Silence (1919) His Wife Got All the Credit (1917) The Story Without a Name (1924) The Gamblers (1919) He Had to Camouflage (1917) Detained (1924) In Honor's Web (1919) Paging Page Two (1917) The Guilty One (1924) The Buried Treasure (1919) A Family Flivver (1917) Bluff (1924) The Guardian of the Accolade (1919) The Renaissance at Charleroi (1917) When a Girl Loves (1924) A Stitch in Time (1919) The Bottom of the Well (1917) Don't Call It Love (1923) Shocks of Doom (1919) The Furnished Room (1917) The Ten Commandments (1923) The Girl Problem (1919) The Defeat of the City (1917) The Marriage Maker (1923) Transients in Arcadia (1918) Richard the Brazen (1917) Racing Hearts (1923) A Bird of Bagdad (1918) The Dazzling Miss Davison (1917) The Heart Raider (1923) Springtime à la Carte (1918) The Mirror (1917) A Daughter of Luxury (1922) Mammon and the Archer (1918) Hedda Gabler (1917) Clarence (1922) One Thousand Dollars (1918) The Debt (1917) Borderland (1922) The Girl and the Graft (1918) Mrs. -

Teacher Support Materials to Use With

Teacher support materials to use with Brief Plot Summary Discussion Questions Historical Drawings and Photos for Discussion Detailed Plot Summary Historical Background What Did You Read? – Form Book Report – Form Word Play Activity Fill in the Blanks Review Activity Brief Plot Summary For Gold and Blood tells the story of two Chinese brothers, Soo and Ping Lee, who, like many Chinese immigrants, leave their home in China to go to California in 1851. They hope to strike it rich in the Gold Rush and send money back to their family. In the gold fields, they make a big strike but are cheated out of it. After 12 years of prospecting, they split up. Soo joins the Chinese workers who build the Central Pacific Railroad, while Ping opens a laundry in San Francisco. With little to show for his work, Soo also goes to San Francisco. Both men face prejudice and violence. In time they join rival factions in the community of Chinatown, Ping with one of the Chinese Six Families and Soo with a secret, illegal tong. The story ends after the 1906 earthquake. This dramatic historical novel portrays the complicated lives of typical immigrants from China and many other countries. Think about it For Gold and Blood Discussion Questions Chapter 1 Leaving Home 1. If you were Ping, would you leave home for the possibility of finding gold so far away? 2. The brothers had to pay money to get out of the country. Does that happen now? 3. Do you think it’s possible to get rich fast without breaking the law? 4. -

The Bates Student

Bates College SCARAB The aB tes Student Archives and Special Collections 5-1911 The aB tes Student - volume 39 number 05 - May 1911 Bates College Follow this and additional works at: http://scarab.bates.edu/bates_student Recommended Citation Bates College, "The aB tes Student - volume 39 number 05 - May 1911" (1911). The Bates Student. 1826. http://scarab.bates.edu/bates_student/1826 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the Archives and Special Collections at SCARAB. It has been accepted for inclusion in The aB tes Student by an authorized administrator of SCARAB. For more information, please contact [email protected]. w TM STVMNT MAY 1911„ ■■ • CONTENTS A My Mother Walter James Graham, ' 11 The Cynic of Parker Hall Alton Rocs Hodgkins, '11 145 Two Flag* Irving Hill Blake, '11 149 Dante Vincent Gatto, '14 150 Editorial 155 Local 159 Athletic* 163 Alumni 169 Exchanges • ' .'.:■■ 175 Spice Box 177 - s ■BMB BUSINESS DIRECTORY THE GLOBE STEAM LAUNDRY, 26-36 Temple Street, PORTLAND MUSIC HALL A. P. BIBBER, Manager The Home of High-Class Vaudeville Prices, 5 and 10 Cents Reserved Seats at Night, 15 Cents MOTION PICTURES CALL AT THB STUDIO of FLAGG ©• PLUMMER For the most up-to-date work in Photography OPPOSITE MUSIC HALL BATES FIRST-GLASS WORK STATIONERY AT In Box and Tablet Form Engraving for Commencement Merrill k Butter's A SPECIALTY % Berry Paper Company 189 Main Street, Cor. Park 49 Lisbon Street, LEWISTON BENJAMIN CLOTHES Always attract attention among the college fellows, because they have the snap and style that other lines do not have You can buy these clothes for the next thirty days at a reduction of over 20 per cent L. -

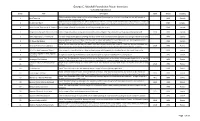

GCMF Poster Inventory

George C. Marshall Foundation Poster Inventory Compiled August 2011 ID No. Title Description Date Period Country A black and white image except for the yellow background. A standing man in a suit is reaching into his right pocket to 1 Back Them Up WWI Canada contribute to the Canadian war effort. A black and white image except for yellow background. There is a smiling soldier in the foreground pointing horizontally to 4 It's Men We Want WWI Canada the right. In the background there is a column of soldiers march in the direction indicated by the foreground soldier's arm. 6 Souscrivez à L'Emprunt de la "Victoire" A color image of a wide-eyed soldier in uniform pointing at the viewer. WWI Canada 2 Bring Him Home with the Victory Loan A color image of a soldier sitting with his gun in his arms and gear. The ocean and two ships are in the background. 1918 WWI Canada 3 Votre Argent plus 5 1/2 d'interet This color image shows gold coins falling into open hands from a Canadian bond against a blue background and red frame. WWI Canada A young blonde girl with a red bow in her hair with a concerned look on her face. Next to her are building blocks which 5 Oh Please Do! Daddy WWI Canada spell out "Buy me a Victory Bond" . There is a gray background against the color image. Poster Text: In memory of the Belgian soldiers who died for their country-The Union of France for Belgium and Allied and 7 Union de France Pour La Belqiue 1916 WWI France Friendly Countries- in the Church of St. -

Films Refusés, Du Moins En Première Instance, Par La Censure 1913-1916 N.B

Films refusés, du moins en première instance, par la censure 1913-1916 N.B. : Ce tableau dresse, d’après les archives de la Régie du cinéma, la liste de tous les refus prononcés par le Bureau de la censure à l’égard d’une version de film soumise pour approbation. Comme de nombreux films ont été soumis plus d’une fois, dans des versions différentes, chaque refus successif fait l’objet d’une nouvelle ligne. La date est celle de la décision. Les « Remarques » sont reproduites telles qu’elles se trouvent dans les documents originaux, accompagnées parfois de commentaires entre [ ]. 001 16 avr 1913 As in a looking glass Monopole 3 rouleaux suggestifs. Condamné. 002 17 avr 1913 The way of the transgressor American Depicting crime. 003 17 avr 1913 White treachery American ? 004 18 avr 1913 Satan Ambrosio Cut out second scene as degrading to Christianity. Third scene: cut out monk intoxicated and other acts of crime. Forth scene: murder and acts of nonsense. 005 23 avr 1913 When men leave home Imperial ? 006 26 avr 1913 Sang noir Eclair ? 007 30 avr 1913 Father Beauclaire Reliance Muckery [=grossièretés]. 008 02 mai 1913 The Wayward son Kalem Too exciting. Burglary. 009 03 mai 1913 The auto bandits of Paris Eclair ? 010 05 mai 1913 Awakening of Papita Nestor ? 011 05 mai 1913 The Last Kiss Pasquali Adultère. (The chauffeur dream) 012 06 mai 1913 Dream dances Edison ? 013 06 mai 1913 Taps Bison Far too much flags; cut flags of U.S. war. A picture with no meaning. [Note du Dr. -

Folly's Queen, Or, Women Whose Loves Have Ruled The

"WE WON'T GO HOME TILL MORNINGI" OR, Women lose Loves Have Ruled the World. LIFE SKETCHES OF THE MOST FAMOUS BELLES OF CUPID'S COURT FOR TWO CENTURIES, / BY JULIE BE MORJEMAR. SUPERBLY ILLUSTRATED. FUE&SHED BY RICHARD K. FOX, PROPRIETOR POLICE GAZETTE, 483 WILLIAM STREET, N. Y. Entered according to Act of Congress, in the year 1882, by RICHARD X FOX, Publisher of the Police Gazette, • NEW YOBK, . Inthe Office of the Librarian of Congress, at Washington. CONTENTS. CHAITEB. 1.-FISH-GIRL AND KING'S MISTRESS. 11.-THE QUEEN OF KINGS AND MOTHER OF REVOLUTIONS. 111.-AN EMPEROR'S AMOUR. IV.-FROM PALACE TO HOVEL. • V.—THE MISFORTUNES OF A LAWLESS GENIUS. VI.—A DESTROYER OF MEN. VII.—THE COST OF AFALSE STEP. VIIL—A MADGENIUS. IX.-ASIREN OF OLD NEW YORK. X.—A QUEEN OF DIAMONDS. XI.—THE FAVORITE OF A TYRANT. Xn.—CAPTURING A PRINCE'S HEART. XIII.—MAJOR YELVERTON'S WIFE. XIV.—THE AMERICANBELLE WHO SOLD HERSELF FOR A TITLE. XV.—CRIME HAUNTED. FOLLY'S QUEENS. CHAPTEB L FISE-GIBL AND KING'S MX3TBES9 , Those who have made Satan's character a The moral that their lives teach is all that etudy tellas that his rulingpolicy in winningiconcerns us. Letus glance at that ofone of the world to himself is to select handsome IFolly's fairest sovereigns, merry Nell women with brilliantintellects for his adju- Gwynne. tants. And facts and our own observation This"tThis "archest of hussies" was born in the compel us toadmit, ungallant as itis, that the little towtown of Hereford, England. -

Seeking Shelter in His Refuge…. Finding, Facing and Fighting Amyloidosis

Seeking Shelter in His Refuge…. Finding, Facing and Fighting Amyloidosis Andrea Barshay Williams Greetings! God put a desire on my heart to capture the last several years of my life and all that it encompassed on paper. When the spirit within you moves the process flows, and the result one would hope will be productive. Who will I offer this project to I wondered? It became clearer as time moved forward. There are three audiences listed below that I think this writing may serve. So, if you are choosing to continue on and take this journey, I sincerely wish that your investment in time proves to be a blessing. The journey of life is comprised of a web of obstacles, learning, opportunities, and growth in the following areas: physical, psychological, emotional, social and most importantly spiritual. Amyloidosis and my writing about it has certainly affected each of these areas in my life. 1- To my family and friends- I was very grateful for the many people who stood with me in whatever capacity, some from the inception of my hematology problems, others just catching wind of my issues at the transplant stage. I hope that reading my story will capture the lessons learned in my journey and that it will draw us even closer as friends and family while emphasizing something I never thought possible, that you can grow even in the belly of the whale. 2- To fellow patients and caretakers- I want to have something tangible to offer others who are and will be diagnosed with my disease, or a related blood disorder or go through a stem cell transplant. -

The American Indian in the American Film

THE AMERICAN INDIAN IN THE AMERICAN FILM Thesis presented in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in American Studies in the University of Canterbury by Michael J. Brathwaite 1981 ABSTRACT This thesis is a chronological examination of the ways in which American Indians have been portrayed in American 1 f.ilms and the factors influencing these portrayals. B eginning with the literary precedents, the effects of three wars and other social upheavals and changes are considered. In addition t-0 being the first objective detailed examination of the subj�ct in English, it is the first work to cover the last decade. It concludes that because of psychological factors it is unlikely that film-makers are - capable of advancing far beyond the basic stereotypes, and that the failure of Indians to appreciate this has repeatedly caused ill-feeling between themselves and the film-makers, making the latter abandon their attempts at a fair treatment of the Indians. ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Preface iii Chapter I: The Background of the Problem c.1630 to c.1900. 1 Chapter II: The Birth of the Cinema and Its Aftermath: 1889 to 1939. 21 Chapter III: World War II and Its Effects: 1940 to 1955. 42 Chapter IV: Assimilation of Separatism?: 1953 to 1965. 65 Chapter V: The Accuracy Question. 80 Chapter VI: Catch-22: 1965 to 1972. 105 Chapter VII: Back to the Beginning: 1973 to 1981. 136 Chapter VIII: Conclusion. 153 Bibliography 156 iii PREFACE The aim of this the.sis is to examine the ways in which the American Indians have been portrayed in American films, the influences on their portrayals, and whether or not they have changed. -

Films Refusés, Du Moins En Première Instance, Par La Censure 1917-1926 N.B

Films refusés, du moins en première instance, par la censure 1917-1926 N.B. : Ce tableau dresse, d’après les archives de la Régie du cinéma, la liste de tous les refus prononcés par le Bureau de la censure à l’égard d’une version de film soumise pour approbation. Comme de nombreux films ont été soumis plus d’une fois, dans des versions différentes, chaque refus successif fait l’objet d’une nouvelle ligne. La date est celle de la décision. Les « Remarques » sont reproduites telles qu’elles se trouvent dans les documents originaux, accompagnées parfois de commentaires entre [ ]. 1632 02 janv 1917 The wager Metro Immoral and criminal; commissioner of police in league with crooks to commit a frame-up robbery to win a wager. 1633 04 janv 1917 Blood money Bison Criminal and a very low type. 1634 04 janv 1917 The moral right Imperial Murder. 1635 05 janv 1917 The piper price Blue Bird Infidelity and not in good taste. 1636 08 janv 1917 Intolerance Griffith [Version modifiée]. Scafold scenes; naked woman; man in death cell; massacre; fights and murder; peeping thow kay hole and girl fixing her stocking; scenes in temple of love; raiding bawdy house; kissing and hugging; naked statue; girls half clad. 1637 09 janv 1917 Redeeming love Morosco Too much caricature on a clergyman; cabaret gambling and filthy scenes. 1638 12 janv 1917 Kick in Pathé Criminal and low. 1639 12 janv 1917 Her New-York Pathé With a tendency to immorality. 1640 12 janv 1917 Double room mystery Red Murder; robbery and of low type. -

A Magazine of Verse Edited by Harriet Monroe

Vol. XI No. II A Magazine of Verse Edited by Harriet Monroe November, 1917 Prize Awards War Poem by Carl Sandburg New Mexico Songs by Alice Corbin 543 Cass Street. Chicago $2.00 per year Single Numbers 20c The livest art in America today is poetry, and the livest expression of that art is in his little Chicago monthly. New York Tribune (Editorial) POETRY for NOVEMBER 1917 PAGE The Four Brothers Carl Sandburg 59 Two Sonnets H. Thompson Rich 67 I Come Singing—Afterwards Reciprocity John Drinkwater 68 November Marjorie Allen Seiffert 69 On the Beach at Fontana—Alone—She Weeps over Rahoon James Joyce 70 A Poet's Epitaph John Black 71 Barefoot Sandals Mary White Slater 72 Lavender Archie Austin Coates 73 Moods and Moments David O'Neil 74 Child Eyes—Freedom—Human Chords—Enslaved—The Peasants—The Beach—Reaches of the Desert—The Ascent My Nicaragua—Two, Spanish Folk-Songs Salomon de la Selva 77 The Dead Pecos Town Kate Buss 81 New Mexico Songs Alice Corbin 82 Los Conquistadores—Three Men—Old Timer—Pedro Montoya—In the Sierras—A Song from Old Spain Comment: A Word to the Carping Critic H. M. 89 Irony, Laforgue and Some Satire .... Ezra Pound 93 Reviews: William H. Davies, Poet Ezra Pound 99 A Modern Solitary H. M. 103 The Old Gods H. M. 105 For Children H. M. 106 Other Books of Verse H. M. and H. H. 107 Correspondence: Coals of Fire from the Cowboy Poet . Badger Clark 109 Announcement of Awards 111 Notes and Books Received 113 No manuscript will be returned unless accompanied by a stamped and self-addressed envelope. -

Lost Silent Feature Films

List of 7200 Lost U.S. Silent Feature Films 1912-29 (last updated 11/16/16) Please note that this compilation is a work in progress, and updates will be posted here regularly. Each listing contains a hyperlink to its entry in our searchable database which features additional information on each title. The database lists approximately 11,000 silent features of four reels or more, and includes both lost films – 7200 as identified here – and approximately 3800 surviving titles of one reel or more. A film in which only a fragment, trailer, outtakes or stills survive is listed as a lost film, however “incomplete” films in which at least one full reel survives are not listed as lost. Please direct any questions or report any errors/suggested changes to Steve Leggett at [email protected] $1,000 Reward (1923) Adam And Evil (1927) $30,000 (1920) Adele (1919) $5,000 Reward (1918) Adopted Son, The (1917) $5,000,000 Counterfeiting Plot, The (1914) Adorable Deceiver , The (1926) 1915 World's Championship Series (1915) Adorable Savage, The (1920) 2 Girls Wanted (1927) Adventure In Hearts, An (1919) 23 1/2 Hours' Leave (1919) Adventure Shop, The (1919) 30 Below Zero (1926) Adventure (1925) 39 East (1920) Adventurer, The (1917) 40-Horse Hawkins (1924) Adventurer, The (1920) 40th Door, The (1924) Adventurer, The (1928) 45 Calibre War (1929) Adventures Of A Boy Scout, The (1915) 813 (1920) Adventures Of Buffalo Bill, The (1917) Abandonment, The (1916) Adventures Of Carol, The (1917) Abie's Imported Bride (1925) Adventures Of Kathlyn, The (1916) Ableminded Lady,