Yuri Tsivian

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Cutting Patterns in DW Griffith's Biographs

Cutting patterns in D.W. Griffith’s Biographs: An experimental statistical study Mike Baxter, 16 Lady Bay Road, West Bridgford, Nottingham, NG2 5BJ, U.K. (e-mail: [email protected]) 1 Introduction A number of recent studies have examined statistical methods for investigating cutting patterns within films, for the purposes of comparing patterns across films and/or for summarising ‘average’ patterns in a body of films. The present paper investigates how different ideas that have been proposed might be combined to identify subsets of similarly constructed films (i.e. exhibiting comparable cutting structures) within a larger body. The ideas explored are illustrated using a sample of 62 D.W Griffith Biograph one-reelers from the years 1909–1913. Yuri Tsivian has suggested that ‘all films are different as far as their SL struc- tures; yet some are less different than others’. Barry Salt, with specific reference to the question of whether or not Griffith’s Biographs ‘have the same large scale variations in their shot lengths along the length of the film’ says the ‘answer to this is quite clearly, no’. This judgment is based on smooths of the data using seventh degree trendlines and the observation that these ‘are nearly all quite different one from another, and too varied to allow any grouping that could be matched against, say, genre’1. While the basis for Salt’s view is clear Tsivian’s apparently oppos- ing position that some films are ‘less different than others’ seems to me to be a reasonably incontestable sentiment. It depends on how much you are prepared to simplify structure by smoothing in order to effect comparisons. -

Papéis Normativos E Práticas Sociais

Agnes Ayres (1898-194): Rodolfo Valentino e Agnes Ayres em “The Sheik” (1921) The Donovan Affair (1929) The Affairs of Anatol (1921) The Rubaiyat of a Scotch Highball Broken Hearted (1929) Cappy Ricks (1921) (1918) Bye, Bye, Buddy (1929) Too Much Speed (1921) Their Godson (1918) Into the Night (1928) The Love Special (1921) Sweets of the Sour (1918) The Lady of Victories (1928) Forbidden Fruit (1921) Coals for the Fire (1918) Eve's Love Letters (1927) The Furnace (1920) Their Anniversary Feast (1918) The Son of the Sheik (1926) Held by the Enemy (1920) A Four Cornered Triangle (1918) Morals for Men (1925) Go and Get It (1920) Seeking an Oversoul (1918) The Awful Truth (1925) The Inner Voice (1920) A Little Ouija Work (1918) Her Market Value (1925) A Modern Salome (1920) The Purple Dress (1918) Tomorrow's Love (1925) The Ghost of a Chance (1919) His Wife's Hero (1917) Worldly Goods (1924) Sacred Silence (1919) His Wife Got All the Credit (1917) The Story Without a Name (1924) The Gamblers (1919) He Had to Camouflage (1917) Detained (1924) In Honor's Web (1919) Paging Page Two (1917) The Guilty One (1924) The Buried Treasure (1919) A Family Flivver (1917) Bluff (1924) The Guardian of the Accolade (1919) The Renaissance at Charleroi (1917) When a Girl Loves (1924) A Stitch in Time (1919) The Bottom of the Well (1917) Don't Call It Love (1923) Shocks of Doom (1919) The Furnished Room (1917) The Ten Commandments (1923) The Girl Problem (1919) The Defeat of the City (1917) The Marriage Maker (1923) Transients in Arcadia (1918) Richard the Brazen (1917) Racing Hearts (1923) A Bird of Bagdad (1918) The Dazzling Miss Davison (1917) The Heart Raider (1923) Springtime à la Carte (1918) The Mirror (1917) A Daughter of Luxury (1922) Mammon and the Archer (1918) Hedda Gabler (1917) Clarence (1922) One Thousand Dollars (1918) The Debt (1917) Borderland (1922) The Girl and the Graft (1918) Mrs. -

Teacher Support Materials to Use With

Teacher support materials to use with Brief Plot Summary Discussion Questions Historical Drawings and Photos for Discussion Detailed Plot Summary Historical Background What Did You Read? – Form Book Report – Form Word Play Activity Fill in the Blanks Review Activity Brief Plot Summary For Gold and Blood tells the story of two Chinese brothers, Soo and Ping Lee, who, like many Chinese immigrants, leave their home in China to go to California in 1851. They hope to strike it rich in the Gold Rush and send money back to their family. In the gold fields, they make a big strike but are cheated out of it. After 12 years of prospecting, they split up. Soo joins the Chinese workers who build the Central Pacific Railroad, while Ping opens a laundry in San Francisco. With little to show for his work, Soo also goes to San Francisco. Both men face prejudice and violence. In time they join rival factions in the community of Chinatown, Ping with one of the Chinese Six Families and Soo with a secret, illegal tong. The story ends after the 1906 earthquake. This dramatic historical novel portrays the complicated lives of typical immigrants from China and many other countries. Think about it For Gold and Blood Discussion Questions Chapter 1 Leaving Home 1. If you were Ping, would you leave home for the possibility of finding gold so far away? 2. The brothers had to pay money to get out of the country. Does that happen now? 3. Do you think it’s possible to get rich fast without breaking the law? 4. -

"Our Own Flesh and Blood?": Delaware Indians and Moravians in the Eighteenth-Century Ohio Country

Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports 2017 "Our Own Flesh and Blood?": Delaware Indians and Moravians in the Eighteenth-Century Ohio Country. Jennifer L. Miller Follow this and additional works at: https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd Recommended Citation Miller, Jennifer L., ""Our Own Flesh and Blood?": Delaware Indians and Moravians in the Eighteenth- Century Ohio Country." (2017). Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports. 8183. https://researchrepository.wvu.edu/etd/8183 This Dissertation is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by the The Research Repository @ WVU with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Dissertation in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you must obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/ or on the work itself. This Dissertation has been accepted for inclusion in WVU Graduate Theses, Dissertations, and Problem Reports collection by an authorized administrator of The Research Repository @ WVU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “Our Own Flesh and Blood?”: Delaware Indians and Moravians in the Eighteenth-Century Ohio Country Jennifer L. Miller Dissertation submitted to the Eberly College of Arts and Sciences At West Virginia University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History Tyler Boulware, Ph.D., chair Melissa Bingmann, Ph.D. Joseph Hodge, Ph.D. Brian Luskey, Ph.D. Rachel Wheeler, Ph.D. Department of History Morgantown, West Virginia 2017 Keywords: Moravians, Delaware Indians, Ohio Country, Pennsylvania, Seven Years’ War, American Revolution, Bethlehem, Gnadenhütten, Schoenbrunn Copyright 2017 Jennifer L. -

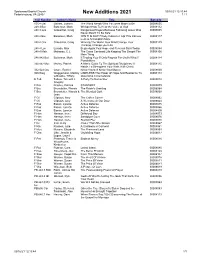

New Additions 2021 1 / 1

Spotswood Baptist Church 03/16/21 12:10:44 Federicksburg, VA 22407 New Additions 2021 1 / 1 Call Number Author's Name Title Barcode 155.4 Gai Gaines, Joanna The World Needs Who You were Made to Be 00008055 248.3 Bat Batterson, Mark Whisper:How To Hear the Voice of God 00008112 248.3 Gro Groeschel, Craig Dangerous Prayers:Because Following Jesus Was 00008095 Never Meant To Be Safe 248.4 Bat Batterson, Mark WIN THE DAY:7 Daily Habits to Help YOu bStress 00008117 Less & Accomplish More 248.4 Gro Groeschel, Craig Winning The WarIn Your Mind:Change Your 00008129 Thinking, Change your Life 248.4 Luc Lucado, Max Begin Again:Your Hope and Renewal Start Today 00008054 248.4 Mah Mahaney, C.J. The Cross Centered Life:Keeping The Gospel The 00008106 Main Thing 248.842 Bat Batterson, Mark If:Trading Your If Only Regrets For God's What If 00008114 Possibilities 248.842 Mor Morley, Patrick A Man's Guide To The Spiritual Disciplines:12 00008115 Habits To Strengthen Your Walk With Christ 332.024 Cru Cruze, Rachel Know Yourself Know Your Money 00008060 920 Weg Weggemann, Mallory LIMITLESS:The Power Of Hope And Resilience To 00008118 w/Brooks, Tiffany Overcome Circumstance E Teb Tebow, Tim w/A.J. A Party To Remember 00008018 Gregory F Bra Bradley, Patricia STANDOFF 00008079 F Bru Brunstetter, Wanda The Robin's Greeting 00008084 F Bru Brunstetter, Wanda & The Blended Quilt 00008068 Jean F Cli Clipston, Amy The Coffee Corner 00008062 F Cli Clipston, Amy A Welcome At Our Door 00008064 F Eas Eason, Lynette Active Defense 00008015 F Eas Eason, Lynette Active -

The Bates Student

Bates College SCARAB The aB tes Student Archives and Special Collections 5-1911 The aB tes Student - volume 39 number 05 - May 1911 Bates College Follow this and additional works at: http://scarab.bates.edu/bates_student Recommended Citation Bates College, "The aB tes Student - volume 39 number 05 - May 1911" (1911). The Bates Student. 1826. http://scarab.bates.edu/bates_student/1826 This Newspaper is brought to you for free and open access by the Archives and Special Collections at SCARAB. It has been accepted for inclusion in The aB tes Student by an authorized administrator of SCARAB. For more information, please contact [email protected]. w TM STVMNT MAY 1911„ ■■ • CONTENTS A My Mother Walter James Graham, ' 11 The Cynic of Parker Hall Alton Rocs Hodgkins, '11 145 Two Flag* Irving Hill Blake, '11 149 Dante Vincent Gatto, '14 150 Editorial 155 Local 159 Athletic* 163 Alumni 169 Exchanges • ' .'.:■■ 175 Spice Box 177 - s ■BMB BUSINESS DIRECTORY THE GLOBE STEAM LAUNDRY, 26-36 Temple Street, PORTLAND MUSIC HALL A. P. BIBBER, Manager The Home of High-Class Vaudeville Prices, 5 and 10 Cents Reserved Seats at Night, 15 Cents MOTION PICTURES CALL AT THB STUDIO of FLAGG ©• PLUMMER For the most up-to-date work in Photography OPPOSITE MUSIC HALL BATES FIRST-GLASS WORK STATIONERY AT In Box and Tablet Form Engraving for Commencement Merrill k Butter's A SPECIALTY % Berry Paper Company 189 Main Street, Cor. Park 49 Lisbon Street, LEWISTON BENJAMIN CLOTHES Always attract attention among the college fellows, because they have the snap and style that other lines do not have You can buy these clothes for the next thirty days at a reduction of over 20 per cent L. -

GCMF Poster Inventory

George C. Marshall Foundation Poster Inventory Compiled August 2011 ID No. Title Description Date Period Country A black and white image except for the yellow background. A standing man in a suit is reaching into his right pocket to 1 Back Them Up WWI Canada contribute to the Canadian war effort. A black and white image except for yellow background. There is a smiling soldier in the foreground pointing horizontally to 4 It's Men We Want WWI Canada the right. In the background there is a column of soldiers march in the direction indicated by the foreground soldier's arm. 6 Souscrivez à L'Emprunt de la "Victoire" A color image of a wide-eyed soldier in uniform pointing at the viewer. WWI Canada 2 Bring Him Home with the Victory Loan A color image of a soldier sitting with his gun in his arms and gear. The ocean and two ships are in the background. 1918 WWI Canada 3 Votre Argent plus 5 1/2 d'interet This color image shows gold coins falling into open hands from a Canadian bond against a blue background and red frame. WWI Canada A young blonde girl with a red bow in her hair with a concerned look on her face. Next to her are building blocks which 5 Oh Please Do! Daddy WWI Canada spell out "Buy me a Victory Bond" . There is a gray background against the color image. Poster Text: In memory of the Belgian soldiers who died for their country-The Union of France for Belgium and Allied and 7 Union de France Pour La Belqiue 1916 WWI France Friendly Countries- in the Church of St. -

Those Crazy Lay Fiduciaries

Fall 2019 DDelawareelaware Vol. 15 No. 4 BBankeranker Those Crazy Lay Fiduciaries What to Watch for When Working with Them COLLABORATION builds better solutions for your clients. For more than a century, we have helped individuals and families thrive with our comprehensive wealth management solutions. Let’s work together to provide your clients with the resources to meet their complex needs. For more information about how we can help you achieve your goals, call Nick Adams at 302.636.6103 or Tony Lunger at 302.651.8743. wilmingtontrust.com Wilmington Trust is a registered service mark. Wilmington Trust Corporation is a wholly owned subsidiary of M&T Bank Corporation. ©2019 Wilmington Trust Corporation and its affiliates. All rights reserved. 33937 191016 VF $ ? Fall 2019 DBA ! Vol. 15, No. 4 Delaware Bankers Association The Delaware Bankers Association P.O. Box 781 Dover, DE 19903-0781 Phone: (302) 678-8600 Fax: (302) 678-5511 www.debankers.com The Quarterly Publication of the Delaware Bankers Association BOARD OF DIRECTORS $ CHAIR Elizabeth D. Albano P. 10 P. 14 P. 24 Executive Vice President Artisans’ Bank CHAIR-ELECT PAST-CHAIR Joe Westcott Cynthia D.M. Brown Market President President Capital One ? Commonwealth Trust Company DIRECTORS-AT-LARGE Thomas M. Forrest Eric G. Hoerner President & CEO Chief Executive Officer U.S. Trust Company of Delaware MidCoast Community Bank DIRECTORS Dominic C. Canuso Lisa P. Kirkwood Contents EVP & Chief Financial Officer SVP, Regional Vice President WSFS Bank TD Bank View from the Chair ................................................................. 4 Larry Drexler Nicholas P. Lambrow President’s Report ..................................................................... 6 Gen. Counsel, Head of Legal & Chief President, Delaware Region What’s New at the DBA ........................................................ -

Idioms-And-Expressions.Pdf

Idioms and Expressions by David Holmes A method for learning and remembering idioms and expressions I wrote this model as a teaching device during the time I was working in Bangkok, Thai- land, as a legal editor and language consultant, with one of the Big Four Legal and Tax companies, KPMG (during my afternoon job) after teaching at the university. When I had no legal documents to edit and no individual advising to do (which was quite frequently) I would sit at my desk, (like some old character out of a Charles Dickens’ novel) and prepare language materials to be used for helping professionals who had learned English as a second language—for even up to fifteen years in school—but who were still unable to follow a movie in English, understand the World News on TV, or converse in a colloquial style, because they’d never had a chance to hear and learn com- mon, everyday expressions such as, “It’s a done deal!” or “Drop whatever you’re doing.” Because misunderstandings of such idioms and expressions frequently caused miscom- munication between our management teams and foreign clients, I was asked to try to as- sist. I am happy to be able to share the materials that follow, such as they are, in the hope that they may be of some use and benefit to others. The simple teaching device I used was three-fold: 1. Make a note of an idiom/expression 2. Define and explain it in understandable words (including synonyms.) 3. Give at least three sample sentences to illustrate how the expression is used in context. -

Simple English Propers for the Ordinary Form of Mass Sundays and Feasts Ii Iii

i Simple engliSh properS For the ordinary Form of mass Sundays and Feasts ii iii Simple english propers For the ordinary Form of mass Sundays and Feasts including formulaic chant settings of entrance, offertory and Communion Antiphons with pointed psalm Verses Composed and Edited by Adam Bartlett with an introduction by Jeffrey A. Tucker church music association of america iv Simple English Propers is licensed in the Creative Commons, 2011 CmAA Antiphon text translations by Solesmes Abbey, licensed in the Creative Commons. psalm verses are taken from The Revised Grail Psalms Copyright © 2010, Conception Abbey/The grail, admin. by GIA publications, inc., www.giamusic.com All rights reserved. psalm tones for introit modes 1, 2, 4, 5, 6, 8, offertory modes 1, 5, and Communion modes 1, 2, 5, 7, 8 by Fr. Samuel F. Weber, o.S.B., © St. meinrad Archabbey, licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-noncommercial- no Derivative Works 3.0 United States license. psalm tones for introit modes 3, 7, offertory modes 2, 3, 4, 6, 8, and Communion modes 3, 6 by Adam Bartlett, licensed in the Creative Commons. psalm tone for Communion mode 4 excerpted from the meinrad Tones, © St. meinrad Archabbey, licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution- noncommercial-no Derivative Works 3.0 United States license. Chant engravings done in gregorio (http://home.gna.org/gregorio/) This book was engraved, typeset and designed by Steven van roode, Breda, the netherlands. Cover art: A page from a 15th c. gradual by Francesco di Antonio del Chierico (b. 1433, d. 1484, Firenze). The manuscript is an illumination of the chant Ad te levavi, the introit for the First Sunday of Advent. -

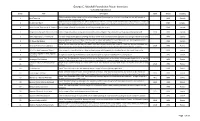

Films Refusés, Du Moins En Première Instance, Par La Censure 1913-1916 N.B

Films refusés, du moins en première instance, par la censure 1913-1916 N.B. : Ce tableau dresse, d’après les archives de la Régie du cinéma, la liste de tous les refus prononcés par le Bureau de la censure à l’égard d’une version de film soumise pour approbation. Comme de nombreux films ont été soumis plus d’une fois, dans des versions différentes, chaque refus successif fait l’objet d’une nouvelle ligne. La date est celle de la décision. Les « Remarques » sont reproduites telles qu’elles se trouvent dans les documents originaux, accompagnées parfois de commentaires entre [ ]. 001 16 avr 1913 As in a looking glass Monopole 3 rouleaux suggestifs. Condamné. 002 17 avr 1913 The way of the transgressor American Depicting crime. 003 17 avr 1913 White treachery American ? 004 18 avr 1913 Satan Ambrosio Cut out second scene as degrading to Christianity. Third scene: cut out monk intoxicated and other acts of crime. Forth scene: murder and acts of nonsense. 005 23 avr 1913 When men leave home Imperial ? 006 26 avr 1913 Sang noir Eclair ? 007 30 avr 1913 Father Beauclaire Reliance Muckery [=grossièretés]. 008 02 mai 1913 The Wayward son Kalem Too exciting. Burglary. 009 03 mai 1913 The auto bandits of Paris Eclair ? 010 05 mai 1913 Awakening of Papita Nestor ? 011 05 mai 1913 The Last Kiss Pasquali Adultère. (The chauffeur dream) 012 06 mai 1913 Dream dances Edison ? 013 06 mai 1913 Taps Bison Far too much flags; cut flags of U.S. war. A picture with no meaning. [Note du Dr. -

Part I – Essay Questions and Selected Answers

Florida Board of Bar Examiners ADMINISTRATIVE BOARD OF THE SUPREME COURT OF FLORIDA Florida Bar Examination Study Guide and Selected Answers July 2014 February 2015 This Study Guide is published semiannually with essay questions from two previously administered examinations and sample answers. Future scheduled release dates: March 2016 and August 2016 No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior written consent of the Florida Board of Bar Examiners. Copyright 2015 by Florida Board of Bar Examiners All rights reserved. TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS ................................................................................................... i PART I – ESSAY QUESTIONS AND SELECTED ANSWERS ...................................... 1 ESSAY EXAMINATION INSTRUCTIONS ....................................................................... 2 JULY 2014 BAR EXAMINATION – CONTRACTS/UNIFORM COMMERCIAL CODE/ETHICS ......................................................................................................... 3 JULY 2014 BAR EXAMINATION – TORTS/CONTRACTS/ETHICS ...................... 11 JULY 2014 BAR EXAMINATION – TRUSTS ......................................................... 17 FEBRUARY 2015 BAR EXAMINATION – FAMILY LAW AND DEPENDENCY ..... 22 FEBRUARY 2015 BAR EXAMINATION – FEDERAL CONSTITUTIONAL LAW/TORTS/ETHICS ............................................................................................ 27 FEBRUARY 2015 BAR EXAMINATION – REAL PROPERTY ..............................