Opioid Prescriber Resource Guide

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Update on the Management of Pain, Agitation, and Delirium in the ICU

Update on the Management of Pain, Agitation, and Delirium in the ICU Kevin E. Anger, Pharm.D., BCPS Gilles Fraser, Pharm.D., MCCM Paul M. Szumita, Pharm.D., BCCCP, Manager Investigational Drug Clinical Pharmacist in Critical BCPS, FCCM Service Brigham and Women’s Care Clinical Pharmacy Practice Manager Hospital Maine Medical Center Brigham and Women’s Hospital Boston, Massachusetts Portland, Maine Boston, Massachusetts Disclosures • Faculty have nothing to disclose. Objectives • Describe recent literature on management of pain, agitation, and delirium (PAD) in the intensive care unit (ICU). • Apply key concepts in the selection of sedatives, analgesics, and antipsychotic agents in critically ill patients. • Recommend methods to overcome key barriers to optimizing pain, sedation, and delirium pharmacotherapy in critically ill patients. Case-Based Approach to Pain Management in the ICU Kevin E. Anger, Pharm.D., BCPS Manager Investigational Drug Service Brigham and Women’s Hospital Boston, Massachusetts Time for a Poll How to vote via the web or text messaging From any browser From a text message Pollev.com/ashp 22333 152964 How to vote via text message How to vote via the web Question #1 DT is a 70 yo male w/ COPD, S/P XRT for NSC lung CA, now admitted to the medical ICU for respiratory failure secondary to pneumonia meeting ARDS criteria. Significant home medications include oxycodone sustained release 40mg TID, oxycodone 10- 20mg Q4hrs PRN pain, Advair 500/50mcg BID, ASA 81mg QD, and albuterol neb Q4hrs PRN. DT is intubated is currently -

Pharmacists' Roles on the Pain Management Team, Fall 2014

Fall 2014, Volume 8, Issue 2 Canadian Pharmacy > Research > Health Policy > Practice > Better Health Pharmacists’ Roles on the Pain Management Team harmacists are an important resource for managing pain in their patients, in order to both optimize treatment and Pprevent the unintended consequences of potent analgesics. While the role of pharmacists in pain management was first addressed inthe Translator Summer 2012 edition1, this rapidly evolving area of pharmacy practice has generated a number of innovative models that highlight the unique role of the pharmacist. As Canadian pharmacists embrace expanded scopes of practice, there is an opportunity to specifically leverage their services to assist patients in managing their pain. This issue of the Translator highlights four different approaches to enhanced involvement of pharmacists in the management of chronic pain: n Pharmacist-led management of chronic pain: a randomized controlled exploratory trial from the UK n A pharmacist-initiated intervention trial in osteoarthritis n A pharmacist-led pain consultation for patients with concomitant substance use disorders n The impact of pharmacists in translating evidence to patients with low back pain 1 The Translator, Summer 2012, 6:3 Pharmacist-led management of chronic pain in primary care: results from a randomized controlled exploratory trial Bruhn H, Bond CM, Elliott AM, et al. Pharmacist-led management of chronic pain in primary care; results from a randomized controlled exploratory trial. BMJ Open 2013;3:e002361. Issue: In the UK, an estimated 80% of medication review of each patient’s medical chronic pain sufferers still report pain after Pharmacist prescribing and records, followed by a face-to-face consul- four years of follow-up.1 Most patients refer reviewing pain medication may tation. -

Pain Management in People Who Have OUD; Acute Vs. Chronic Pain

Pain Management in People Who Have OUD; Acute vs. Chronic Pain Developer: Stephen A. Wyatt, DO Medical Director, Addiction Medicine Carolinas HealthCare System Reviewer/Editor: Miriam Komaromy, MD, The ECHO Institute™ This project is supported by the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) under contract number HHSH250201600015C. This information or content and conclusions are those of the author and should not be construed as the official position or policy of, nor should any endorsements be inferred by HRSA, HHS or the U.S. Government. Disclosures Stephen Wyatt has nothing to disclose Objectives • Understand the complexities of treating acute and chronic pain in patients with opioid use disorder (OUD). • Understand the various approaches to treating the OUD patient on an agonist medication for acute or chronic pain. • Understand how acute and chronic pain can be treated when the OUD patient is on an antagonist medication. Speaker Notes: The general Outline of the module is to first address the difficulties surrounding treating pain in the opioid dependent patient. Then to address the ways that patients with pain can be approached on either an agonist of antagonist opioid use disorder treatment. Pain and Substance Use Disorder • Potential for mutual mistrust: – Provider • drug seeking • dependency/intolerance • fear – Patient • lack of empathy • avoidance • fear Speaker Notes: It is the provider that needs to be well educated and skillful in working with this population. Through a better understanding of opioid use disorders as a disease, the prejudice surrounding the encounter with the patient may be reduced. -

Perioperative Pain Management for the Chronic Pain Patient with Long-Term Opioid Use

1.5 ANCC Contact Hours Perioperative Pain Management for the Chronic Pain Patient With Long-Term Opioid Use Carina Jackman In the United States nearly one in four patients present- patterns of preoperative opioid use. Approximately one ing for surgery reports current opioid use. Many of these in four patients undergoing surgery in the study re- patients suffer from chronic pain disorders and opioid ported preoperative opioid use (23.1% of the 34,186-pa- tolerance or dependence. Opioid tolerance and preexisting tient study population). Opioid use was most common chronic pain disorders present unique challenges in regard in patients undergoing orthopaedic spinal surgery to postoperative pain management. These patients benefi t (65%). This was followed by neurosurgical spinal sur- geries (55.1%). Hydrocodone bitartrate was the most from providers who are not only familiar with multimodal prevalent medication. Tramadol and oxycodone hydro- pain management and skilled in the assessment of acute pain, chloride were also common ( Hilliard et al., 2018 ). but also empathetic to their specifi c struggles. Chronic pain Given this signifi cant population of surgical patients patients often face stigmas surrounding their opioid use, with established opioid use, it is imperative for both and this may lead to underestimation and undertreatment nurses and all other providers to gain an understanding of their pain. This article aims to review the challenges of the complex challenges chronic pain patients intro- presented by these complex patients and provide strate- duce to the postoperative setting. gies for treating acute postoperative pain in opioid-tolerant patients. Defi nitions Common pain terminology as defined by the Chronic Pain and Long-Term International Association for the Study of Pain, a joint Opioid Use consensus statement by the American Society of Addiction Medicine, the American Academy of Pain The burden of chronic pain in the United States is stag- Medicine and the American Pain Society (2001 ), and the gering. -

Menu of Pain Management Clinic Regulation

Menu of Pain Management Clinic Regulation The United States is in the midst of an unprecedented epidemic of prescription drug overdose deaths.1 More than 38,000 people died of drug overdoses in 2010, and most of these deaths (22,134) were caused by overdoses involving prescription drugs.2 Three-quarters of prescription drug overdose deaths in 2010 (16,651) involved a prescription opioid pain reliever (OPR), which is a drug derived from the opium poppy or synthetic versions of it such as oxycodone, hydrocodone, or methadone.3 The prescription drug overdose epidemic has not affected all states equally, and overdose death rates vary widely between states. States have the primary responsibility to regulate and enforce prescription drug practice. Although state laws are commonly used to prevent injuries and their benefits have been demonstrated for a variety of injury types,4 there is little information on the effectiveness of state statutes and regulations designed to prevent prescription drug abuse and diversion. This menu is a first step in assessing pain management clinic laws by creating an inventory of state legal strategies in this domain. Introduction One type of law aimed at preventing inappropriate prescribing is regulation of pain management clinics, often called “pill mills” when they are sources of large quantities of prescriptions. Pill mills have become an increasing problem in the prescription drug epidemic, and laws have been enacted to prevent these facilities from prescribing controlled substances inappropriately. A law was included in this resource as a pain management clinic regulation if it requires state oversight and contains other requirements concerning ownership and operation of pain management clinics, facilities, or practice locations. -

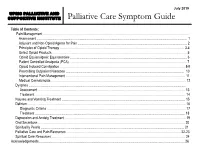

Palliative Care Symptom Guide

July 2019 UPMC PALLIATIVE AND SUPPORTIVE INSTITUTE Palliative Care Symptom Guide Table of Contents: Pain Management ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….. Assessment …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 1 Adjuvant and Non-Opioid Agents for Pain ……………………………………………………………………………………….... 2 Principles of Opioid Therapy ……………………………………………………………………………………………….….…. 3-4 Select Opioid Products ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 5 Opioid Equianalgesic Equivalencies ………………………………………………………………………...…………………..… 6 Patient Controlled Analgesia (PCA) ……………………………………………………………………………………………….. 7 Opioid Induced Constipation ……………………………………………………………………………………………………… 8-9 Prescribing Outpatient Naloxone ………………………………………………………………………………………………… 10 Interventional Pain Management …………………………………………………………………………………………………. 11 Medical Cannabinoids ……………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 12 Dyspnea ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… Assessment ………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 13 Treatment …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………… 14 Nausea and Vomiting Treatment ……………………………………………………………………………………………..……… 15 Delirium …………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………. 16 Diagnostic Criteria ……………………………………………………………………………….……………………….………... 17 Treatment ………………………………………………………………………………..…………………………………………. 18 Depression and Anxiety Treatment ……………………………………………………..…………..…………………………….…. 19 Oral Secretions ……………………………………………………..…………………………………………………………………. 20 Spirituality Pearls ……………………………………………………..………………………………………………………………. 21 Palliative -

Veterinary Anesthesia and Pain Management Secrets / Edited by Stephen A

Publisher: HANLEY & BELFUS, INC. Medical Publishers 210 South 13th Street Philadelphia, PA 19107 (215) 546-7293; 800-962-1892 FAX (215) 790-9330 Web site: http://www.hanleyandbelfus.com Note to the reader Although the information in this book has been carefully reviewed for cor rectness of dosage and indications, neither the authors nor the editor nor the publisher can accept any legal responsibility for any errors or omissions that may be made. Neither the publisher nor the editor makes any warranty, expressed or implied, with respect to the material contained herein. Before prescribing any drug. the reader must review the manu facturer's correct product information (package inserts) for accepted indications, absolute dosage recommendations. and other information pertinent to the safe and effective use of the product described. This is especially important when drugs are given in combination or as an adjunct to other forms of therapy Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Veterinary anesthesia and pain management secrets / edited by Stephen A. Greene. p. em. - (The Secrets Series®) Includes bibliographical references (p.). ISBN 1-56053-442-7 (alk paper) I. Veterinary anesthesia-Examinations, questions. etc. 2. Pain in animals Treatment-Examinations, questions, etc. I. Greene, Stephen A., 1956-11. Series. SF914.V48 2002 636 089' 796'076--dc2 I 2001039966 VETERINARY ANESTHESIA AND PAIN MANAGEMENT SECRETS ISBN 1-56053-442-7 © 2002 by Hanley & Belfus, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be repro duced, reused, republished. or transmitted in any form, or stored in a database or retrieval system, without written permission of the publisher Last digit is the print number: 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 CONTRIBUTORS G. -

Pain Management & Palliative Care

Guidelines on Pain Management & Palliative Care A. Paez Borda (chair), F. Charnay-Sonnek, V. Fonteyne, E.G. Papaioannou © European Association of Urology 2013 TABLE OF CONTENTS PAGE 1. INTRODUCTION 6 1.1 The Guideline 6 1.2 Methodology 6 1.3 Publication history 6 1.4 Acknowledgements 6 1.5 Level of evidence and grade of guideline recommendations* 6 1.6 References 7 2. BACKGROUND 7 2.1 Definition of pain 7 2.2 Pain evaluation and measurement 7 2.2.1 Pain evaluation 7 2.2.2 Assessing pain intensity and quality of life (QoL) 8 2.3 References 9 3. CANCER PAIN MANAGEMENT (GENERAL) 10 3.1 Classification of cancer pain 10 3.2 General principles of cancer pain management 10 3.3 Non-pharmacological therapies 11 3.3.1 Surgery 11 3.3.2 Radionuclides 11 3.3.2.1 Clinical background 11 3.3.2.2 Radiopharmaceuticals 11 3.3.3 Radiotherapy for metastatic bone pain 13 3.3.3.1 Clinical background 13 3.3.3.2 Radiotherapy scheme 13 3.3.3.3 Spinal cord compression 13 3.3.3.4 Pathological fractures 14 3.3.3.5 Side effects 14 3.3.4 Psychological and adjunctive therapy 14 3.3.4.1 Psychological therapies 14 3.3.4.2 Adjunctive therapy 14 3.4 Pharmacotherapy 15 3.4.1 Chemotherapy 15 3.4.2 Bisphosphonates 15 3.4.2.1 Mechanisms of action 15 3.4.2.2 Effects and side effects 15 3.4.3 Denosumab 16 3.4.4 Systemic analgesic pharmacotherapy - the analgesic ladder 16 3.4.4.1 Non-opioid analgesics 17 3.4.4.2 Opioid analgesics 17 3.4.5 Treatment of neuropathic pain 21 3.4.5.1 Antidepressants 21 3.4.5.2 Anticonvulsant medication 21 3.4.5.3 Local analgesics 22 3.4.5.4 NMDA receptor antagonists 22 3.4.5.5 Other drug treatments 23 3.4.5.6 Invasive analgesic techniques 23 3.4.6 Breakthrough cancer pain 24 3.5 Quality of life (QoL) 25 3.6 Conclusions 26 3.7 References 26 4. -

Managing Pain Anywhere

Managing Pain – Anywhere! The Role of the Pharmacist Lee Kral, PharmD, BCPS The University of Iowa Center for Pain Medicine November 2012 Outline 1. Patient care settings 2. Barriers to pharmacist involvement 3. Establishing a practice 4. Qualifications, resources 5. Benefits/outcomes Where is the Pain? Outpatient clinics ER Hospital OR/PACU Inpatient units Discharge Do YOU do pain management in your practice? YES NO Pharmacist involvement in pain management Practice sites Hospital settings Emergency Department – acute pain 21% Outpatient clinics – chronic pain 45% 12% Inpatient units – acute and/or chronic pain 22% Critical care Palliative Care Community hospitals Oncology Federal hospitals Surgery Hospice Adult Medicine Other OR/PACU – acute pain Where do PPC pharmacists come from? Providers perceive need Pharmacy department initiative Sentinel events, safety issues Drug diversion/enforcement concerns Joint Commission mandates Gradual practice transition (fam med, hem-onc) Pain management practice model shift Which of the following is something that a PPC pharmacist might do? a. Prescribe opioids b. Order urine toxicology c. Obtain medication histories d. Write orders for post-op pain in the PACU e. All of the above What are the barriers? Pharmacist lack of knowledge, expertise Budgetary constraints Resistance from medical staff Providers unfamiliar with qualifications Ignorance of nursing, medical, pharmacy staff Unclear role of the pharmacist Previously established methods Lack of mentorship What are the qualifications? PGY-2 Pain and Palliative Care residency Certified Pain Educator (ASPE) ASHP PPC traineeship American Academy of Pain Management Certificate programs Experience and interest Juba KM. J Pharmacy Practice 2012; 00(0):1-4 What are the outcomes? Clinic setting1 Generated > $100,000 annual true revenue Saved health plans > $455,000 annually Reduce pain scores Managed maintenance monitoring Opioid refill clinic2 Reduced drug costs Reduced utilization of health care services Provider satisfaction Improved patient behavior 1. -

Post- Operative Pain- Relief

PPoosstt-- OOppeerraattiivvee PPaaiinn-- RReelliieeff • Pain is often the patient’s presenting symptom. It can provide useful clinical information and it is your responsibility to use this information to help the patient and alleviate suffering. • Manage pain wherever you see patients (emergency, operating room and on the ward) and anticipate their needs for pain management after surgery and discharge. • Do not unnecessarily delay the treatment of pain; for example, do not transport a patient without analgesia simply so that the next practitioner can appreciate how much pain the person is experiencing. • Pain management is our job. Pain Management and Techniques • Effective analgesia is an essential part of postoperative management. • Important injectable drugs for pain are the opiate analgesics. Nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs), such as diclofenac (1 mg/kg) and ibuprofen can also be given orally and rectally, as can paracetamol (15 mg/kg). • There are three situations where an opiate might be given: pre- operatively, intra-operatively, post-operatively. •• Opiate premedication is rarely indicated, although an injured patient in pain may have been given an opiate before coming to the operating room. • Opiates given pre- or intraoperatively have important effects in the postoperative period since there may be delayed recovery and respiratory depression, even necessitating mechanical ventilation. (continued to next page) PPoosstt-- OOppeerraattiivvee PPaaiinn-- RReelliieeff ((ccoonnttiiinnuueedd)) • Short acting opiate fentanyl is used intra-operatively to avoid this prolonged effect. • Naloxone antagonizes (reverses) all opiates, but its effect quickly wears off. • Commonly available inexpensive opiates are pethidine and morphine. • Morphine has about ten times the potency and a longer duration of action than pethidine. -

Pain Management in Patients with Substance-Use Disorders

Pain Management in Patients with Substance-Use Disorders By Valerie Prince, Pharm.D., FAPhA, BCPS Reviewed by Beth A. Sproule, Pharm.D.; Jeffrey T. Sherer, Pharm.D., MPH, BCPS; and Patricia H. Powell, Pharm.D., BCPS Learning Objectives regarding drug interactions with illicit substances or prescribed pain medications. Finally, there are issues 1. Construct a therapeutic plan to overcome barri- ers to effective pain management in a patient with related to the comorbidities of the patient with addic- addiction. tion (e.g., psychiatric disorders or physical concerns 2. Distinguish high-risk patients from low-risk patients related to the addiction) that should influence product regarding use of opioids to manage pain. selection. 3. Design a treatment plan for the management of acute pain in a patient with addiction. Epidemiology 4. Design a pharmacotherapy plan for a patient with Pain is the second most common cause of work- coexisting addiction and chronic noncancer pain. place absenteeism. The prevalence of chronic pain may 5. Design a pain management plan that encompasses be much higher among patients with substance use dis- recommended nonpharmacologic components for orders than among the general population. In the 2006 a patient with a history of substance abuse. National Survey on Drug Use and Health, past-year alco- hol addiction or abuse occurred in 10.3% of men and 5.1% of women. In the same survey, 12.3% of men and Introduction 6.3% of women were reported as having a substance-use Pain, which is one of the most common reasons disorder (abuse or addiction) during the past year. -

Pain Terminology for Family Caregivers

Information for Family Caregivers Pain Terminology for Family Caregivers Term Definition Comment/Importance to Caregiving Pain An unpleasant physical and • Understanding the pain helps you share emotional experience important information with healthcare associated with or described in providers that can help to guide your terms of actual or potential treatment plan tissue damage • “Pain is whatever the older adult says it is, occurring whenever he/she says it does” TYPES OF PAIN Term Definition Comment/Importance to Caregiving Acute Pain Pain that is usually temporary • Understanding the type of pain helps you and results from something share important information that can help to specific, such as a surgery, an guide the treatment plan injury, or an infection. • Ineffectively treated acute pain can turn into chronic pain Chronic Pain A painful experience that • Also called persistent pain continues for a prolonged • It is estimated up to 80% of individuals living period that may or may not be in nursing homes have chronic pain associated with a disease, • A variety of diagnosis contribute to chronic typically 3 months or longer. pain in this population, including: osteoarthritis, cancer, post-stroke pain, diabetic peripheral neuropathy, and others Musculoskeletal Pain of the muscles, joints, • This pain is relatively well localized and is Pain connective tissues and bones. typically worse on movement • This type of pain is often described as a dull, or ‘background’ aching pain, although the area may be tender to pressure Breakthrough Pain that increases above the • Associated with cancer pain Pain level of pain addressed by • Reported in 2 out of 3 people with continuous ongoing analgesics.