Pain Management & Palliative Care

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

RELISTOR, INN: Methylnaltrexone Bromide

The European Medicines Agency Evaluation of Medicines for Human Use EMEA/CHMP/10906/2008 ASSESSMENT REPORT FOR RELISTOR International Nonproprietary Name: METHYLNALTREXONE BROMIDE Procedure No. EMEA/H/C/870 Assessment Report as adopted by the CHMP with all information of a commercially confidential nature deleted. 7 Westferry Circus, Canary Wharf, London, E14 4HB, UK Tel. (44-20) 74 18 84 00 Fax (44-20) 74 18 8613 E-mail: [email protected] http://www.emea.eu.int TABLE OF CONTENTS Page 1 BACKGROUND INFORMATION ON THE PROCEDURE......................................... 3 1.1 Submission of the dossier ...................................................................................................... 3 1.2 Steps taken for the assessment of the product ....................................................................... 3 2 SCIENTIFIC DISCUSSION............................................................................................... 4 2.1 Introduction............................................................................................................................ 4 2.2 Quality aspects....................................................................................................................... 5 2.3 Non-clinical aspects............................................................................................................... 7 2.4 Clinical aspects .................................................................................................................... 13 2.5 Pharmacovigilance...............................................................................................................41 -

Albany-Molecular-Research-Regulatory

PRODUCT CATALOGUE API COMMERCIAL US EU Japan US EU Japan API Name Site CEP India API Name Site CEP India DMF DMF DMF DMF DMF DMF A Abiraterone Malta • Benztropine Mesylate Cedarburg • Adenosine Rozzano - Quinto de' Stampi • • * Betaine Citrate Anhydrous Bon Encontre • Betametasone-17,21- Alcaftadine Spain Spain • • Dipropionate Sterile • Alclometasone-17, 21- Spain Betamethasone Acetate Spain Dipropionate • • Altrenogest Spain • • Betamethasone Base Spain Amphetamine Aspartate Rensselaer Betamethasone Benzoate Spain * Monohydrate Milled • Betamethasone Valerate Amphetamine Sulfate Rensselaer Spain * • Acetate Betamethasone-17,21- Argatroban Rozzano - Quinto de' Stampi Spain • • Dipropionate • • • Atenolol India • • Betamethasone-17-Valerate Spain • • Betamethasone-21- Atracurium Besylate Rozzano - Quinto de' Stampi Spain • Phosphate Disodium Salt • • Bromfenac Monosodium Atropine Sulfate Cedarburg Lodi * • Salt Sesquihydrate • • Azanidazole Lodi Bromocriptine Mesylate Rozzano - Quinto de' Stampi • • • • • Azelastine HCl Rozzano - Quinto de' Stampi • • Budesonide Spain • • Aztreonam Rozzano - Valle Ambrosia • • Budesonide Sterile Spain • • B Bamifylline HCl Bon Encontre • Butorphanol Tartrate Cedarburg • Beclomethasone-17, 21- Spain Capecitabine Lodi Dipropionate • C • 2 *Please contact our Accounts Managers in case you are interested in this API. 3 PRODUCT CATALOGUE API COMMERCIAL US EU Japan US EU Japan API Name Site CEP India API Name Site CEP India DMF DMF DMF DMF DMF DMF Dexamethasone-17,21- Carbimazole Bon Encontre Spain • Dipropionate -

Design and Synthesis of Cyclic Analogs of the Kappa Opioid Receptor Antagonist Arodyn

Design and synthesis of cyclic analogs of the kappa opioid receptor antagonist arodyn By © 2018 Solomon Aguta Gisemba Submitted to the graduate degree program in Medicinal Chemistry and the Graduate Faculty of the University of Kansas in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. Chair: Dr. Blake Peterson Co-Chair: Dr. Jane Aldrich Dr. Michael Rafferty Dr. Teruna Siahaan Dr. Thomas Tolbert Date Defended: 18 April 2018 The dissertation committee for Solomon Aguta Gisemba certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Design and synthesis of cyclic analogs of the kappa opioid receptor antagonist arodyn Chair: Dr. Blake Peterson Co-Chair: Dr. Jane Aldrich Date Approved: 10 June 2018 ii Abstract Opioid receptors are important therapeutic targets for mood disorders and pain. Kappa opioid receptor (KOR) antagonists have recently shown potential for treating drug addiction and 1,2,3 4 8 depression. Arodyn (Ac[Phe ,Arg ,D-Ala ]Dyn A(1-11)-NH2), an acetylated dynorphin A (Dyn A) analog, has demonstrated potent and selective KOR antagonism, but can be rapidly metabolized by proteases. Cyclization of arodyn could enhance metabolic stability and potentially stabilize the bioactive conformation to give potent and selective analogs. Accordingly, novel cyclization strategies utilizing ring closing metathesis (RCM) were pursued. However, side reactions involving olefin isomerization of O-allyl groups limited the scope of the RCM reactions, and their use to explore structure-activity relationships of aromatic residues. Here we developed synthetic methodology in a model dipeptide study to facilitate RCM involving Tyr(All) residues. Optimized conditions that included microwave heating and the use of isomerization suppressants were applied to the synthesis of cyclic arodyn analogs. -

A Review of Unique Opioids and Their Conversions

A Review of Unique Opioids and Their Conversions Jacqueline Cleary, PharmD, BCACP Assistant Professor Albany College of Pharmacy and Health Sciences Adjunct Professor SAGE College of Nursing DISCLOSURES • Kaleo • Remitigate, LLC OBJECTIVES • Compare and contrast unique pharmacotherapy options for the treatment of chronic pain including: methadone, buprenoprhine, tapentadol, and tramadol • Select methadone, buprenorphine, tapentadol, or tramadol based on patient specific factors • Apply appropriate opioid conversion strategies to unique opioids • Understand opioid overdose risk surrounding opioid conversions and the use of unique opioids UNIQUE OPIOIDS METHADONE, BUPRENORPHINE, TRAMADOL, TAPENTADOL METHADONE My favorite drug because….? METHADONE- INDICATIONS • FDA labeled indications – (1) chronic pain (2) detoxification Oral soluble tablets for suspension NOT indicated for chronic pain treatment • Initial inpatient detoxification of opioids by a licensed trained provider with methadone and supportive care is appropriate • Methadone maintenance provider must have special credentialing and training as required by state Outpatient prescription must be for pain ONLY and say “for pain” on RX • Continuation of methadone maintenance from outside provider while patient is inpatient for another condition is appropriate http://cdn.atforum.com/wp-content/uploads/SAMHSA-2015-Guidelines-for-OTPs.pdf MECHANISM OF ACTION • Potent µ-opioid agonist • NMDA receptor antagonist • Norepinephrine reuptake inhibitor • Serotonin reuptake inhibitor ADVERSE EVENTS -

Clinical Data Mining Reveals Analgesic Effects of Lapatinib in Cancer Patients

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Clinical data mining reveals analgesic efects of lapatinib in cancer patients Shuo Zhou1,2, Fang Zheng1,2* & Chang‑Guo Zhan1,2* Microsomal prostaglandin E2 synthase 1 (mPGES‑1) is recognized as a promising target for a next generation of anti‑infammatory drugs that are not expected to have the side efects of currently available anti‑infammatory drugs. Lapatinib, an FDA‑approved drug for cancer treatment, has recently been identifed as an mPGES‑1 inhibitor. But the efcacy of lapatinib as an analgesic remains to be evaluated. In the present clinical data mining (CDM) study, we have collected and analyzed all lapatinib‑related clinical data retrieved from clinicaltrials.gov. Our CDM utilized a meta‑analysis protocol, but the clinical data analyzed were not limited to the primary and secondary outcomes of clinical trials, unlike conventional meta‑analyses. All the pain‑related data were used to determine the numbers and odd ratios (ORs) of various forms of pain in cancer patients with lapatinib treatment. The ORs, 95% confdence intervals, and P values for the diferences in pain were calculated and the heterogeneous data across the trials were evaluated. For all forms of pain analyzed, the patients received lapatinib treatment have a reduced occurrence (OR 0.79; CI 0.70–0.89; P = 0.0002 for the overall efect). According to our CDM results, available clinical data for 12,765 patients enrolled in 20 randomized clinical trials indicate that lapatinib therapy is associated with a signifcant reduction in various forms of pain, including musculoskeletal pain, bone pain, headache, arthralgia, and pain in extremity, in cancer patients. -

Approach to Polyarthritis for the Primary Care Physician

24 Osteopathic Family Physician (2018) 24 - 31 Osteopathic Family Physician | Volume 10, No. 5 | September / October, 2018 REVIEW ARTICLE Approach to Polyarthritis for the Primary Care Physician Arielle Freilich, DO, PGY2 & Helaine Larsen, DO Good Samaritan Hospital Medical Center, West Islip, New York KEYWORDS: Complaints of joint pain are commonly seen in clinical practice. Primary care physicians are frequently the frst practitioners to work up these complaints. Polyarthritis can be seen in a multitude of diseases. It Polyarthritis can be a challenging diagnostic process. In this article, we review the approach to diagnosing polyarthritis Synovitis joint pain in the primary care setting. Starting with history and physical, we outline the defning characteristics of various causes of arthralgia. We discuss the use of certain laboratory studies including Joint Pain sedimentation rate, antinuclear antibody, and rheumatoid factor. Aspiration of synovial fuid is often required for diagnosis, and we discuss the interpretation of possible results. Primary care physicians can Rheumatic Disease initiate the evaluation of polyarthralgia, and this article outlines a diagnostic approach. Rheumatology INTRODUCTION PATIENT HISTORY Polyarticular joint pain is a common complaint seen Although laboratory studies can shed much light on a possible diagnosis, a in primary care practices. The diferential diagnosis detailed history and physical examination remain crucial in the evaluation is extensive, thus making the diagnostic process of polyarticular symptoms. The vast diferential for polyarticular pain can difcult. A comprehensive history and physical exam be greatly narrowed using a thorough history. can help point towards the more likely etiology of the complaint. The physician must frst ensure that there are no symptoms pointing towards a more serious Emergencies diagnosis, which may require urgent management or During the initial evaluation, the physician must frst exclude any life- referral. -

Update on the Management of Pain, Agitation, and Delirium in the ICU

Update on the Management of Pain, Agitation, and Delirium in the ICU Kevin E. Anger, Pharm.D., BCPS Gilles Fraser, Pharm.D., MCCM Paul M. Szumita, Pharm.D., BCCCP, Manager Investigational Drug Clinical Pharmacist in Critical BCPS, FCCM Service Brigham and Women’s Care Clinical Pharmacy Practice Manager Hospital Maine Medical Center Brigham and Women’s Hospital Boston, Massachusetts Portland, Maine Boston, Massachusetts Disclosures • Faculty have nothing to disclose. Objectives • Describe recent literature on management of pain, agitation, and delirium (PAD) in the intensive care unit (ICU). • Apply key concepts in the selection of sedatives, analgesics, and antipsychotic agents in critically ill patients. • Recommend methods to overcome key barriers to optimizing pain, sedation, and delirium pharmacotherapy in critically ill patients. Case-Based Approach to Pain Management in the ICU Kevin E. Anger, Pharm.D., BCPS Manager Investigational Drug Service Brigham and Women’s Hospital Boston, Massachusetts Time for a Poll How to vote via the web or text messaging From any browser From a text message Pollev.com/ashp 22333 152964 How to vote via text message How to vote via the web Question #1 DT is a 70 yo male w/ COPD, S/P XRT for NSC lung CA, now admitted to the medical ICU for respiratory failure secondary to pneumonia meeting ARDS criteria. Significant home medications include oxycodone sustained release 40mg TID, oxycodone 10- 20mg Q4hrs PRN pain, Advair 500/50mcg BID, ASA 81mg QD, and albuterol neb Q4hrs PRN. DT is intubated is currently -

Methylnaltrexone Nonf

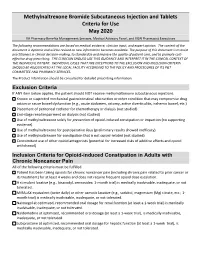

Methylnaltrexone Bromide Subcutaneous Injection and Tablets Criteria for Use May 2020 VA Pharmacy Benefits Management Services, Medical Advisory Panel, and VISN Pharmacist Executives The following recommendations are based on medical evidence, clinician input, and expert opinion. The content of the document is dynamic and will be revised as new information becomes available. The purpose of this document is to assist practitioners in clinical decision-making, to standardize and improve the quality of patient care, and to promote cost- effective drug prescribing. THE CLINICIAN SHOULD USE THIS GUIDANCE AND INTERPRET IT IN THE CLINICAL CONTEXT OF THE INDIVIDUAL PATIENT. INDIVIDUAL CASES THAT ARE EXCEPTIONS TO THE EXCLUSION AND INCLUSION CRITERIA SHOULD BE ADJUDICATED AT THE LOCAL FACILITY ACCORDING TO THE POLICY AND PROCEDURES OF ITS P&T COMMITTEE AND PHARMACY SERVICES. The Product Information should be consulted for detailed prescribing information. Exclusion Criteria If ANY item below applies, the patient should NOT receive methylnaltrexone subcutaneous injections. Known or suspected mechanical gastrointestinal obstruction or other condition that may compromise drug action or cause bowel dysfunction (e.g., acute abdomen, ostomy, active diverticulitis, ischemic bowel, etc.) Placement of peritoneal catheter for chemotherapy or dialysis (not studied) End-stage renal impairment on dialysis (not studied) Use of methylnaltrexone solely for prevention of opioid-induced constipation or impaction (no supporting evidence). Use of methylnaltrexone for postoperative ileus (preliminary results showed inefficacy). Use of methylnaltrexone for constipation that is not opioid-related (not studied) Concomitant use of other opioid antagonists (potential for increased risks of additive effects and opioid withdrawal) Inclusion Criteria for Opioid-induced Constipation in Adults with Chronic Noncancer Pain All of the following criteria must be fulfilled. -

Pathological Cause of Low Back Pain in a Patient Seen Through Direct Margaret M

Pathological Cause of Low Back Pain in a Patient Seen through Direct Margaret M. Gebhardt PT, DPT, OCS Access in a Physical Therapy Clinic: A Case Report Staff Physical Therapist, Motion Stability, LLC, and Adjunct Clinical Faculty, Mercer University, Atlanta, GA ABSTRACT cal therapists primarily treat patients that sporadic.9 Deyo and Diehl6 found that the Background and Purpose: A 66-year- fall into the mechanical LBP category, but 4 clinical findings with the highest positive old male presented directly to a physical need to be aware that although infrequent, likelihood ratios for detecting the presence therapy clinic with complaints of low back 7% to 8% of LBP complaints are due to of cancer in LBP were: a previous history of pain (LBP). The purpose of this case report is nonmechanical spinal conditions or visceral cancer, failure to improve with conservative to describe the clinical reasoning that led to disease.5 Malignant neoplasms are the most medical treatment in the past month, an age a medical referral for a patient not respond- common of the nonmechanical spinal con- of at least 50 years or older, and unexplained ing to conservative treatment that ultimately ditions causing LBP, but comprise less than weight loss of more than 4.5 kg in 6 months led to the diagnosis of multiple myeloma. 1% of all total LBP conditions.6 (Table 1).10 In Deyo and Diehl’s6 study, they Methods: Data was collected during the In this era of autonomous practice, analyzed 1975 patients that presented with course of the patient’s treatment in an out- increasing numbers of physical therapists are LBP and found 13 to have cancer. -

Pharmacists' Roles on the Pain Management Team, Fall 2014

Fall 2014, Volume 8, Issue 2 Canadian Pharmacy > Research > Health Policy > Practice > Better Health Pharmacists’ Roles on the Pain Management Team harmacists are an important resource for managing pain in their patients, in order to both optimize treatment and Pprevent the unintended consequences of potent analgesics. While the role of pharmacists in pain management was first addressed inthe Translator Summer 2012 edition1, this rapidly evolving area of pharmacy practice has generated a number of innovative models that highlight the unique role of the pharmacist. As Canadian pharmacists embrace expanded scopes of practice, there is an opportunity to specifically leverage their services to assist patients in managing their pain. This issue of the Translator highlights four different approaches to enhanced involvement of pharmacists in the management of chronic pain: n Pharmacist-led management of chronic pain: a randomized controlled exploratory trial from the UK n A pharmacist-initiated intervention trial in osteoarthritis n A pharmacist-led pain consultation for patients with concomitant substance use disorders n The impact of pharmacists in translating evidence to patients with low back pain 1 The Translator, Summer 2012, 6:3 Pharmacist-led management of chronic pain in primary care: results from a randomized controlled exploratory trial Bruhn H, Bond CM, Elliott AM, et al. Pharmacist-led management of chronic pain in primary care; results from a randomized controlled exploratory trial. BMJ Open 2013;3:e002361. Issue: In the UK, an estimated 80% of medication review of each patient’s medical chronic pain sufferers still report pain after Pharmacist prescribing and records, followed by a face-to-face consul- four years of follow-up.1 Most patients refer reviewing pain medication may tation. -

Pain Management in People Who Have OUD; Acute Vs. Chronic Pain

Pain Management in People Who Have OUD; Acute vs. Chronic Pain Developer: Stephen A. Wyatt, DO Medical Director, Addiction Medicine Carolinas HealthCare System Reviewer/Editor: Miriam Komaromy, MD, The ECHO Institute™ This project is supported by the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) under contract number HHSH250201600015C. This information or content and conclusions are those of the author and should not be construed as the official position or policy of, nor should any endorsements be inferred by HRSA, HHS or the U.S. Government. Disclosures Stephen Wyatt has nothing to disclose Objectives • Understand the complexities of treating acute and chronic pain in patients with opioid use disorder (OUD). • Understand the various approaches to treating the OUD patient on an agonist medication for acute or chronic pain. • Understand how acute and chronic pain can be treated when the OUD patient is on an antagonist medication. Speaker Notes: The general Outline of the module is to first address the difficulties surrounding treating pain in the opioid dependent patient. Then to address the ways that patients with pain can be approached on either an agonist of antagonist opioid use disorder treatment. Pain and Substance Use Disorder • Potential for mutual mistrust: – Provider • drug seeking • dependency/intolerance • fear – Patient • lack of empathy • avoidance • fear Speaker Notes: It is the provider that needs to be well educated and skillful in working with this population. Through a better understanding of opioid use disorders as a disease, the prejudice surrounding the encounter with the patient may be reduced. -

Perioperative Pain Management for the Chronic Pain Patient with Long-Term Opioid Use

1.5 ANCC Contact Hours Perioperative Pain Management for the Chronic Pain Patient With Long-Term Opioid Use Carina Jackman In the United States nearly one in four patients present- patterns of preoperative opioid use. Approximately one ing for surgery reports current opioid use. Many of these in four patients undergoing surgery in the study re- patients suffer from chronic pain disorders and opioid ported preoperative opioid use (23.1% of the 34,186-pa- tolerance or dependence. Opioid tolerance and preexisting tient study population). Opioid use was most common chronic pain disorders present unique challenges in regard in patients undergoing orthopaedic spinal surgery to postoperative pain management. These patients benefi t (65%). This was followed by neurosurgical spinal sur- geries (55.1%). Hydrocodone bitartrate was the most from providers who are not only familiar with multimodal prevalent medication. Tramadol and oxycodone hydro- pain management and skilled in the assessment of acute pain, chloride were also common ( Hilliard et al., 2018 ). but also empathetic to their specifi c struggles. Chronic pain Given this signifi cant population of surgical patients patients often face stigmas surrounding their opioid use, with established opioid use, it is imperative for both and this may lead to underestimation and undertreatment nurses and all other providers to gain an understanding of their pain. This article aims to review the challenges of the complex challenges chronic pain patients intro- presented by these complex patients and provide strate- duce to the postoperative setting. gies for treating acute postoperative pain in opioid-tolerant patients. Defi nitions Common pain terminology as defined by the Chronic Pain and Long-Term International Association for the Study of Pain, a joint Opioid Use consensus statement by the American Society of Addiction Medicine, the American Academy of Pain The burden of chronic pain in the United States is stag- Medicine and the American Pain Society (2001 ), and the gering.