Veterinary Anesthesia and Pain Management Secrets / Edited by Stephen A

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CHRONIC PAIN in CATS Recent Advances in Clinical Assessment

601_614_Monteiro_Chronic pain3.qxp_FAB 12/06/2019 14:59 Page 601 Journal of Feline Medicine and Surgery (2019) 21, 601–614 CLINICAL REVIEW CHRONIC PAIN IN CATS Recent advances in clinical assessment Beatriz P Monteiro and Paulo V Steagall Negative impacts of chronic pain Practical relevance: Chronic pain is a feline health and welfare issue. It has Domestic animals may now have a long life expectancy, given a negative impact on quality of life and advances in veterinary healthcare; as a consequence, there is an impairs the owner–cat bond. Chronic increased prevalence of chronic conditions associated with pain. pain can exist by itself or may be Chronic pain affects feline health and welfare. It has a negative impact associated with disease and/or injury, on quality of life (QoL) and impairs the owner–cat bond. including osteoarthritis (OA), cancer, and oral Nowadays, chronic pain assessment should be considered a funda- and periodontal disease, among others. mental part of feline practice. Clinical challenges: Chronic pain assessment Indeed, lack of knowledge on is a fundamental part of feline practice, but can be Chronic pain-related changes the subject and the use of appro- challenging due to differences in pain mechanisms in behavior are subtle and priate tools for pain recognition underlying different conditions, and the cat’s natural are some of the reasons why behavior. It relies mostly on owner-assessed likely to be suppressed analgesic administration is com- behavioral changes and time-consuming veterinary monly neglected in cats.1 consultations. Beyond OA – for which disease- in the clinical setting. In chronic pain, changes in specific clinical signs have been described – little behavior are subtle and slow, and is known regarding other feline conditions that may only be evident in the home produce chronic pain. -

Equine Health Studies Program 2008-2010 Equine Research Report

Equine Health Studies Program 2008-2010 Equine Research Report Scientific studies conducted to help advance equine health and well-being LETTER FROM OUR DEAN The Louisiana State University School of Veterinary Medicine is pleased to once again present the Equine Health Studies Program’s Equine Research Report, which covers scientific activities of the program from 2008 through 2010. Central to the program’s mission is the health, well- being and performance of horses supported through state- of-the-art research that benefits the horse-owning public in Louisiana and beyond. As a former equine surgeon and faculty member, I have watched the EHSP grow and flourish, as evidenced by contents of this Research Report, translating research into practical solutions for our broad- base constituents and clients. In addition to its research prowess, the program’s dedicated faculty and staff provide clinical service, education, and community outreach. The EHSP has made significant advances in research collaborations with industry to extend its work in the areas of laminitis prevention; lameness, orthopedics and biomechanics; reproductive disorders; respiratory and gastrointestinal diseases including the treatment and prevention of gastric ulcer disease; equine Cushing’s disease; and surgery that will impact equine veterinary care for years to come. The EHSP continues to build and maintain strong relationships and community engagement with the stakeholders of Louisiana so that it can be responsive to the needs of horses in the region. In the aftermath of Hurricanes Gustav and Ike and the Gulf Oil Spill, the SVM was able to step in and help with the rescue and care of animals and wildlife in south Louisiana. -

Hospital Standards Self-Evaluation Checklist

Hospital Standards Self-Evaluation Checklist July 2017 The Hospital Standards Self-Evaluation Checklist was developed by the Veterinary Medical Board (Board) and its Multidisciplinary Advisory Committee with input from the public and profession in order to assist Hospital Directors’ review of minimum standards to achieve compliance with the law. The Board strongly recommends involvement of the entire staf in a team efort to become familiar with and maintain the minimum standards of practice. Contents INTRODUCTION 1 GENERAL 3 1. After Hours Referral/Hospital Closure. 3 2. License/Permit Displayed . 4 3. Correct Address . 6 4. Notice of No Staff on Premises . 7 FACILITIES 9 5. General Sanitary Conditionsn . 9 6. Temperature and Ventilation. 10 7. Lighting . 10 8. Reception/Offce . 10 9. Exam Rooms . 11 10. Food & Beverage . 11 11. Fire Precautions . 12 12. Oxygen Equipment . 13 13. Emergency Drugs and Equipment. 13 14. Laboratory Services . 13 15. X-ray . 14 16. X-ray Identifcation. 15 17. X-ray Safety Training for Unregistered Assistants . 16 1 8. Waste Disposal . 16 19. Disposal of Animals . 17 20. Freezer. 17 21. Compartments . 18 22. Exercise Runs . 18 23. Contagious Facilities. 19 SURGERY 21 24. Separate Surgery . 21 25. Surgery Lighting/X-ray/Emergency . 22 26. Surgery Floors, Tables and Countertop . 23 27. Endotracheal Tubes . 23 28. Resuscitation Bags . 23 29. Anesthetic Equipment . 24 30. Anesthetic Monitoring . 24 31. Surgical Packs and Sterile Indicators . 25 32. Sterilization of Equipment . 26 33. Sanitary Attire . 26 Hospital Standards Self-Evaluation Checklist i DANGEROUS DRUGS/CONTROLLED SUBSTANCES 29 34. Expired Drug. 29 35. Drug Security Controls . -

001-017-Anesthesia.Pdf

Current Fluid Therapy Topics and Recommendations During Anesthetic Procedures Andrew Claude, DVM, DACVAA Mississippi State University Mississippi State, MS • Intravenous fluid administration is recommended during general anesthesia, even during short procedures. • The traditional IV fluid rate of 10 mls/kg/hr during general anesthesia is under review. • Knowledge of a variety of IV fluids, and their applications, is essential when choosing anesthetic protocols for different medical procedures. Anesthetic drug effects on the cardiovascular system • Almost all anesthetic drugs have the potential to adversely affect the cardiovascular system. • General anesthetic vapors (isoflurane, sevoflurane) cause a dose-dependent, peripheral vasodilation. • Alpha-2 agonists initially cause peripheral hypertension with reflex bradycardia leading to a dose-dependent decreased patient cardiac index. As the drug effects wane, centrally mediated bradycardia and hypotension are common side effects. • Phenothiazine (acepromazine) tranquilizers are central dopamine and peripheral alpha receptor antagonists. This family of drugs produces dose-dependent sedation and peripheral vasodilation (hypotension). • Dissociative NMDA antagonists (ketamine, tiletamine) increase sympathetic tone soon after administration. When dissociative NMDA antagonists are used as induction agents in patients with sympathetic exhaustion or decreased cardiac reserve (morbidly ill patients), these drugs could further depress myocardial contractility. • Propofol can depress both myocardial contractility and vascular tone resulting in marked hypotension. Propofol’s negative effects on the cardiovascular system can be especially problematic in ill patients. • Potent mu agonist opioids can enhance vagally induced bradycardia. Why is IV fluid therapy important during general anesthesia? • Cardiac output (CO) equals heart rate (HR) X stroke volume (SV); IV fluids help maintain adequate fluid volume, preload, and sufficient cardiac output. -

Pharmacology – Inhalant Anesthetics

Pharmacology- Inhalant Anesthetics Lyon Lee DVM PhD DACVA Introduction • Maintenance of general anesthesia is primarily carried out using inhalation anesthetics, although intravenous anesthetics may be used for short procedures. • Inhalation anesthetics provide quicker changes of anesthetic depth than injectable anesthetics, and reversal of central nervous depression is more readily achieved, explaining for its popularity in prolonged anesthesia (less risk of overdosing, less accumulation and quicker recovery) (see table 1) Table 1. Comparison of inhalant and injectable anesthetics Inhalant Technique Injectable Technique Expensive Equipment Cheap (needles, syringes) Patent Airway and high O2 Not necessarily Better control of anesthetic depth Once given, suffer the consequences Ease of elimination (ventilation) Only through metabolism & Excretion Pollution No • Commonly administered inhalant anesthetics include volatile liquids such as isoflurane, halothane, sevoflurane and desflurane, and inorganic gas, nitrous oxide (N2O). Except N2O, these volatile anesthetics are chemically ‘halogenated hydrocarbons’ and all are closely related. • Physical characteristics of volatile anesthetics govern their clinical effects and practicality associated with their use. Table 2. Physical characteristics of some volatile anesthetic agents. (MAC is for man) Name partition coefficient. boiling point MAC % blood /gas oil/gas (deg=C) Nitrous oxide 0.47 1.4 -89 105 Cyclopropane 0.55 11.5 -34 9.2 Halothane 2.4 220 50.2 0.75 Methoxyflurane 11.0 950 104.7 0.2 Enflurane 1.9 98 56.5 1.68 Isoflurane 1.4 97 48.5 1.15 Sevoflurane 0.6 53 58.5 2.5 Desflurane 0.42 18.7 25 5.72 Diethyl ether 12 65 34.6 1.92 Chloroform 8 400 61.2 0.77 Trichloroethylene 9 714 86.7 0.23 • The volatile anesthetics are administered as vapors after their evaporization in devices known as vaporizers. -

Update on the Management of Pain, Agitation, and Delirium in the ICU

Update on the Management of Pain, Agitation, and Delirium in the ICU Kevin E. Anger, Pharm.D., BCPS Gilles Fraser, Pharm.D., MCCM Paul M. Szumita, Pharm.D., BCCCP, Manager Investigational Drug Clinical Pharmacist in Critical BCPS, FCCM Service Brigham and Women’s Care Clinical Pharmacy Practice Manager Hospital Maine Medical Center Brigham and Women’s Hospital Boston, Massachusetts Portland, Maine Boston, Massachusetts Disclosures • Faculty have nothing to disclose. Objectives • Describe recent literature on management of pain, agitation, and delirium (PAD) in the intensive care unit (ICU). • Apply key concepts in the selection of sedatives, analgesics, and antipsychotic agents in critically ill patients. • Recommend methods to overcome key barriers to optimizing pain, sedation, and delirium pharmacotherapy in critically ill patients. Case-Based Approach to Pain Management in the ICU Kevin E. Anger, Pharm.D., BCPS Manager Investigational Drug Service Brigham and Women’s Hospital Boston, Massachusetts Time for a Poll How to vote via the web or text messaging From any browser From a text message Pollev.com/ashp 22333 152964 How to vote via text message How to vote via the web Question #1 DT is a 70 yo male w/ COPD, S/P XRT for NSC lung CA, now admitted to the medical ICU for respiratory failure secondary to pneumonia meeting ARDS criteria. Significant home medications include oxycodone sustained release 40mg TID, oxycodone 10- 20mg Q4hrs PRN pain, Advair 500/50mcg BID, ASA 81mg QD, and albuterol neb Q4hrs PRN. DT is intubated is currently -

Pharmacists' Roles on the Pain Management Team, Fall 2014

Fall 2014, Volume 8, Issue 2 Canadian Pharmacy > Research > Health Policy > Practice > Better Health Pharmacists’ Roles on the Pain Management Team harmacists are an important resource for managing pain in their patients, in order to both optimize treatment and Pprevent the unintended consequences of potent analgesics. While the role of pharmacists in pain management was first addressed inthe Translator Summer 2012 edition1, this rapidly evolving area of pharmacy practice has generated a number of innovative models that highlight the unique role of the pharmacist. As Canadian pharmacists embrace expanded scopes of practice, there is an opportunity to specifically leverage their services to assist patients in managing their pain. This issue of the Translator highlights four different approaches to enhanced involvement of pharmacists in the management of chronic pain: n Pharmacist-led management of chronic pain: a randomized controlled exploratory trial from the UK n A pharmacist-initiated intervention trial in osteoarthritis n A pharmacist-led pain consultation for patients with concomitant substance use disorders n The impact of pharmacists in translating evidence to patients with low back pain 1 The Translator, Summer 2012, 6:3 Pharmacist-led management of chronic pain in primary care: results from a randomized controlled exploratory trial Bruhn H, Bond CM, Elliott AM, et al. Pharmacist-led management of chronic pain in primary care; results from a randomized controlled exploratory trial. BMJ Open 2013;3:e002361. Issue: In the UK, an estimated 80% of medication review of each patient’s medical chronic pain sufferers still report pain after Pharmacist prescribing and records, followed by a face-to-face consul- four years of follow-up.1 Most patients refer reviewing pain medication may tation. -

Femoral Nerve Block Versus Spinal Anesthesia for Lower Limb

Alexandria Journal of Anaesthesia and Intensive Care 44 Femoral Nerve Block versus Spinal Anesthesia for Lower Limb Peripheral Vascular Surgery By Ahmed Mansour, MD Assistant Professor of Anesthesia, Faculty of Medicine, Alexandria University. Abstract Perioperative cardiac complications occur in 4% to 6% of patients undergoing infrainguinal revascularization under general, spinal, or epidural anesthesia. The risk may be even greater in patients whose cardiac disease cannot be fully evaluated or treated before urgent limb salvage operations. Prompted by these considerations, we investigated the feasibility and results of using femoral nerve block with infiltration of the genito4femoral nerve branches in these high-risk patients. Methods: Forty peripheral vascular reconstruction of lower limbs were performed under either spinal anesthesia (20 patients) or femoral nerve block with infiltration of genito-femoral nerve branches supplemented with local infiltration at the site of dissection as needed (20 patients). All patients had arterial lines. Arterial blood pressure and electrocardiographic monitoring was continued during surgery, in PACU and in the intensive care units. Results: Operations included femoral-femoral, femoral-popliteal bypass grafting and thrombectomy. The intra-operative events showed that the mean time needed to perform the block and dose of analgesics and sedatives needed during surgery was greater in group I (FNB,) compared to group II [P=0.01*, P0.029* , P0.039*], however, the time needed to start surgery was shorter in group I than in group II [P=0. 039]. There were no block failures in either group, but local infiltration in the area of the dissection with 2 ml (range 1-5 ml) of 1% lidocaine was required in 4 (20%) patients in FNB group vs none in the spinal group. -

Pain Management in People Who Have OUD; Acute Vs. Chronic Pain

Pain Management in People Who Have OUD; Acute vs. Chronic Pain Developer: Stephen A. Wyatt, DO Medical Director, Addiction Medicine Carolinas HealthCare System Reviewer/Editor: Miriam Komaromy, MD, The ECHO Institute™ This project is supported by the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) under contract number HHSH250201600015C. This information or content and conclusions are those of the author and should not be construed as the official position or policy of, nor should any endorsements be inferred by HRSA, HHS or the U.S. Government. Disclosures Stephen Wyatt has nothing to disclose Objectives • Understand the complexities of treating acute and chronic pain in patients with opioid use disorder (OUD). • Understand the various approaches to treating the OUD patient on an agonist medication for acute or chronic pain. • Understand how acute and chronic pain can be treated when the OUD patient is on an antagonist medication. Speaker Notes: The general Outline of the module is to first address the difficulties surrounding treating pain in the opioid dependent patient. Then to address the ways that patients with pain can be approached on either an agonist of antagonist opioid use disorder treatment. Pain and Substance Use Disorder • Potential for mutual mistrust: – Provider • drug seeking • dependency/intolerance • fear – Patient • lack of empathy • avoidance • fear Speaker Notes: It is the provider that needs to be well educated and skillful in working with this population. Through a better understanding of opioid use disorders as a disease, the prejudice surrounding the encounter with the patient may be reduced. -

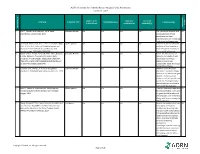

AORN Guideline for Patients Receiving Local-Only Anesthesia Evidence Table

AORN Guideline for Patients Receiving Local-Only Anesthesia Evidence Table SAMPLE SIZE/ CONTROL/ OUTCOME CITATION EVIDENCE TYPE INTERVENTION(S) CONCLUSION(S) POPULATION COMPARISON MEASURE(S) SCORE CONSENSUS REFERENCE # REFERENCE 1 Lirk P., Picardi S. and Hollmann, M. W. Local Literature Review n/a n/a n/a n/a The mechanism of action and VA anaesthetics: 10 essentials. 2014 access pathways of local anesthetics and their pharmokinetics are increasingly understood and appreciated. 2 Calatayud, Jesús, M.D.,D.D.S., Ph.D., González, Õngel, Expert Opinion n/a n/a n/a n/a A review of the discovery and VA M.D., D.D.S., Ph.D. History of the development and evolution of local anesthesia evolution of local anesthesia since the coca leaf. from the Spanish discovery of Anesthesiology. 2003;98(6):1503-1508. the coca leaf in America. 3 Gordh T, M.D., Gordh, Torsten E.,M.D., Ph.D., Lindqvist Literature Review n/a n/a n/a n/a Before the introduction of VA K, M.Sc. Lidocaine: The origin of a modern local lidocaine, the choice of local anesthetic. Anesthesiology. 2010;113(6):1433-1437. anesthetics was limited. https://doi.org/10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181fcef48. doi: Lidocaine's onset was 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3181fcef48. substantially faster and longer lasting than procaine. 4 Volcheck G.W., Mertes, P. M. Local and general Literature Review n/a n/a n/a n/a Whether to test the local VA anesthetics immediate hypersensitivity reactions. 2014 anesthetic causing the allergic reaction or an alternative agent depends on the expected future need of the specific local anesthetic. -

The Use of Buffering Solutions in the Pediatrics Local Anesthesia to Reduce the Pain of Minor Procedures

Volume 2- Issue 1 : 2018 DOI: 10.26717/BJSTR.2018.02.000695 Eduardo de Oliveira Duque-Estrada. Biomed J Sci & Tech Res ISSN: 2574-1241 Mini Review Open Access The Use of Buffering Solutions in the Pediatrics Local Anesthesia to Reduce the Pain of Minor Procedures Eduardo de Oliveira Duque-Estrada MD* Received: January 17, 2018; Published: January 25, 2018 *Corresponding author: Eduardo de Oliveira Duque-Estrada, Ex-Professor of Pediatrics and Pediatric Surgery, Teresópolis Schoolof Medicine, Rio de Janeiro, Rua Jose da Silva Ribeiro 119 apt 11 São Paulo, SP Brazil CEP: 05726-130, Email: Abstract The local anesthetics are widely u sed in minor pediatric surgical procedures. The major problem with their use is the resulted pain experienced by the patients at the time of injection. To discuss those situations in the light of the medical literature we present this mini-review. Key words: Local Injection; Pain; Buffer; pH; Lidocaine; Pediatric Surgery Procedure Introduction Table 1: Techniques for injection pain control*. a eutectic mixture of lidocaine and prilocaine (EMLA) cream [17] S.No Techniques for injection pain control before infiltration, and local external cooling (cryoanalgesia) have 1. Warming the anesthetic solution [18,19] (Table 1). also been used to reduce the pain of infiltration of local anesthetic 2. Buffering the anesthetic Buffering the Anesthetic 3. Injection technique 4. Distraction Local anesthesia is extremely useful either as the sole method the best results on the minor surgery in general [3,6]. Blocking 5. Combination anesthetic technique the pain pathway with local anesthetic solution will also reduce 6. Cooling of skin the family stress response to the surgical procedure. -

Perioperative Pain Management for the Chronic Pain Patient with Long-Term Opioid Use

1.5 ANCC Contact Hours Perioperative Pain Management for the Chronic Pain Patient With Long-Term Opioid Use Carina Jackman In the United States nearly one in four patients present- patterns of preoperative opioid use. Approximately one ing for surgery reports current opioid use. Many of these in four patients undergoing surgery in the study re- patients suffer from chronic pain disorders and opioid ported preoperative opioid use (23.1% of the 34,186-pa- tolerance or dependence. Opioid tolerance and preexisting tient study population). Opioid use was most common chronic pain disorders present unique challenges in regard in patients undergoing orthopaedic spinal surgery to postoperative pain management. These patients benefi t (65%). This was followed by neurosurgical spinal sur- geries (55.1%). Hydrocodone bitartrate was the most from providers who are not only familiar with multimodal prevalent medication. Tramadol and oxycodone hydro- pain management and skilled in the assessment of acute pain, chloride were also common ( Hilliard et al., 2018 ). but also empathetic to their specifi c struggles. Chronic pain Given this signifi cant population of surgical patients patients often face stigmas surrounding their opioid use, with established opioid use, it is imperative for both and this may lead to underestimation and undertreatment nurses and all other providers to gain an understanding of their pain. This article aims to review the challenges of the complex challenges chronic pain patients intro- presented by these complex patients and provide strate- duce to the postoperative setting. gies for treating acute postoperative pain in opioid-tolerant patients. Defi nitions Common pain terminology as defined by the Chronic Pain and Long-Term International Association for the Study of Pain, a joint Opioid Use consensus statement by the American Society of Addiction Medicine, the American Academy of Pain The burden of chronic pain in the United States is stag- Medicine and the American Pain Society (2001 ), and the gering.