CHRONIC PAIN in CATS Recent Advances in Clinical Assessment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Veterinary Medicine, D.V.M

Veterinary Medicine Veterinarians diagnose, treat, and control diseases in animals and Description are concerned with preventing transmission of animal diseases to humans. They treat injured animals and develop programs to prevent disease and injury. Admitted Student Statistics AlphaGenesis Incorporated (AGI) Summer Veterinary Program American Veterinary Medical Association (AVMA); Student AVMA Army Veterinarians: Military Veterinarian Opportunities Association of American Veterinary Medical Colleges (AAVMC); AAVMC Scholarship and Loan Information; AAVMC Webinars Become a Veterinarian Become a Veterinarian and Make a Difference Canadian Veterinary Medical Association (CVMA); Canadian Veterinary Colleges Career Opportunities in Veterinary Medicine Careers in Veterinary Medicine Columbia U. Office of Pre-Professional Advising List of Veterinary Opportunities for Pre-Health Students Cost Comparison of a Veterinary Medical Education Financing Your Veterinary Medical Education Funding a Veterinary Medical Education Interview Questions Loop Abroad College Veterinary Service Program Martindale's Virtual Veterinary Center Massachusetts Veterinary Medical Association Michigan State U. College of Veterinary Medicine Biomedical Research for University Students in Health Sciences (BRUSH) Pre-Veterinary Resources Pre-Veterinary Student Doctor Network Forums Purdue University College of Veterinary Medicine Veterinary Scholars Summer Research Program Rochester Institute of Technology List of Co-op/Internship Opportunities for Prevet Students Scholarships -

Equine Health Studies Program 2008-2010 Equine Research Report

Equine Health Studies Program 2008-2010 Equine Research Report Scientific studies conducted to help advance equine health and well-being LETTER FROM OUR DEAN The Louisiana State University School of Veterinary Medicine is pleased to once again present the Equine Health Studies Program’s Equine Research Report, which covers scientific activities of the program from 2008 through 2010. Central to the program’s mission is the health, well- being and performance of horses supported through state- of-the-art research that benefits the horse-owning public in Louisiana and beyond. As a former equine surgeon and faculty member, I have watched the EHSP grow and flourish, as evidenced by contents of this Research Report, translating research into practical solutions for our broad- base constituents and clients. In addition to its research prowess, the program’s dedicated faculty and staff provide clinical service, education, and community outreach. The EHSP has made significant advances in research collaborations with industry to extend its work in the areas of laminitis prevention; lameness, orthopedics and biomechanics; reproductive disorders; respiratory and gastrointestinal diseases including the treatment and prevention of gastric ulcer disease; equine Cushing’s disease; and surgery that will impact equine veterinary care for years to come. The EHSP continues to build and maintain strong relationships and community engagement with the stakeholders of Louisiana so that it can be responsive to the needs of horses in the region. In the aftermath of Hurricanes Gustav and Ike and the Gulf Oil Spill, the SVM was able to step in and help with the rescue and care of animals and wildlife in south Louisiana. -

Mixed Breed Cats

Mixed Breed Cats: What a Unique Breed! Your cat is special! She senses your moods, is curious about your day, and has purred her way into your heart. Chances are that you chose her because you like Mixed Breed Cats and you expected her to have certain traits that would fit your lifestyle, like: May meow to communicate with you Lively, with a friendly personality Agile, sturdy, and athletic However, no cat is perfect! You may have also noticed these characteristics: Can become overweight easily if not exercised regularly Scratches when bored May be mischievous if not given enough attention Is it all worth it? Of course! She is of a mixed background and can come is all sizes and colors. Her personality is just as varied as her looks, but she makes an excellent companion. Your Mixed Breed Cat's Health We know that because you care so much about your cat, you want to take great care of her. That is why we have summarized the health concerns we will be discussing with you over the life of your cat. By knowing about the health concerns common among cats, we can help you tailor an individual preventive health plan and hopefully prevent some predictable risks in your pet. Many diseases and health conditions are genetic, meaning they are related to your pet’s breed. The conditions we will describe here have a significant rate of incidence or a strong PET MEDICAL CENTER 501 E. FM 2410 ● Harker Heights, Texas 76548 (254) 690-6769 www.pet-medcenter.com impact upon this mixed breed particularly, according to a motivate cats with more food-based interests to romp and general consensus among feline genetic researchers and tumble. -

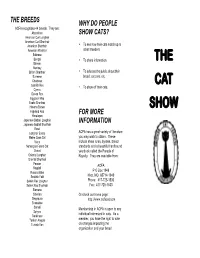

The Cat Show

THE BREEDS WHY DO PEOPLE ACFA recognizes 44 breeds. They are: Abyssinian SHOW CATS? American Curl Longhair American Curl Shorthair • American Shorthair To see how their cats match up to American Wirehair other breeders. Balinese Bengal • To share information. THE Birman Bombay • British Shorthair To educate the public about their Burmese breed, cat care, etc. Chartreux CAT Cornish Rex • To show off their cats. Cymric Devon Rex Egyptian Mau Exotic Shorthair Havana Brown SHOW Highland Fold FOR MORE Himalayan Japanese Bobtail Longhair INFORMATION Japanese Bobtail Shorthair Korat Longhair Exotic ACFA has a great variety of literature Maine Coon Cat you may wish to obtain. These Manx include show rules, bylaws, breed Norwegian Forest Cat standards and a beautiful hardbound Ocicat yearbook called the Parade of Oriental Longhair Royalty. They are available from: Oriental Shorthair Persian ACFA Ragdoll Russian Blue P O Box 1949 Scottish Fold Nixa, MO 65714-1949 Selkirk Rex Longhair Phone: 417-725-1530 Selkirk Rex Shorthair Fax: 417-725-1533 Siamese Siberian Or check our home page: Singapura http://www.acfacat.com Snowshoe Somali Membership in ACFA is open to any Sphynx individual interested in cats. As a Tonkinese Turkish Angora member, you have the right to vote Turkish Van on changes impacting the organization and your breed. AWARDS & RIBBONS WELCOME THE JUDGING Welcome to our cat show! We hope you Each day there will be four or more rings Each cat competes in their class against will enjoy looking at all of the cats we have running concurrently. Each judge acts other cats of the same sex, color and breed. -

Theriogenology Residency at Louisiana State University School of Veterinary Medicine (SVM) Is Designed to Provide Three Years of Post- DVM Training in Theriogenology

RESIDENCY IN THERIOGENOLGY Louisiana State University School of Veterinary Medicine Department of Veterinary Clinical Sciences Veterinary Teaching Hospital Revised September 2016 TABLE OF CONTENTS 1.0 Introduction 2.0 Objectives 3.0 Prerequisites 4.0 Faculty Mentor 5.0 House Officer Rounds and Seminar Program 6.0 Teaching Program 7.0 Board Certification 8.0 Clinical Program 9.0 Research Project 10.0 Graduate Program 11.0 Additional Objectives 12.0 Evaluation and Reappointment 13.0 House Officer Committee 14.0 Employment and Benefits 15.0 Application 16.0 Appendix 16.1 House Officer Rounds Evaluation Form 16.2 VCS Seminar Evaluation Form 16.3 House Officer Leave Request 16.4 House Officer Block Evaluation Form RESIDENCY PROGRAM IN VETERINARY THERIOGENOLOGY Louisiana State University School of Veterinary Medicine Department of Veterinary Clinical Sciences Veterinary Teaching Hospital 1.0 INTRODUCTION 1.1 The Theriogenology residency at Louisiana State University School of Veterinary Medicine (SVM) is designed to provide three years of post- DVM training in Theriogenology. This will partially fulfill the requirements for examination (certification) by the American College of Theriogenologists. The training program will utilize faculty of the Department of Veterinary Clinical Sciences (VCS) and other participating departments as mentors. Clinical facilities of the Veterinary Teaching Hospital (VTH) will be the primary training location. 2.0 OBJECTIVES 2.1 To prepare a candidate to write the board examination of the American College of Theriogenologists (ACT). 2.2 To provide an opportunity to complete a Master’s degree (Thesis option) through the Graduate School and the School of Veterinary Medicine if desired. -

Feline Leukemia Virus (Felv)

Feline Leukemia Virus (FeLV) What is feline leukemia virus (FeLV)? Feline leukemia virus infects cats world-wide. FeLV can suppress the immune system, decreasing the ability of a cat to fight infections. The virus can also cause several types of cancer, such as leukemia and lymphoma. In the United States, about 2%-3% of all cats are infected with FeLV. The viral infection is diagnosed by a blood test performed at a veterinary clinic. How do cats get this virus? Cats get FeLV from other cats that are infected. An infected cat can shed the virus in their saliva, nasal fluids, urine, feces and milk. The virus can be transmitted between cats through bite wounds, mutual grooming, sharing food dishes, and from mother to kitten. What happens once a cat is infected? Every cat infected with FeLV will go down one of two paths: 1. The cat’s immune system is able to fight off infection within the first 2-6 weeks. The cat will show no signs of illness and the virus will go into an inactive state. These cats are unlikely to transmit the disease to another cat. 2. The cat’s FeLV test remains positive for more than 16 weeks. These cats will likely not be able to fight off infection and will likely develop FeLV associated diseases within a few years. Cats in this stage have a higher likelihood of being able to transmit the disease to another cat. The only way to determine the outcome of each cat is through a repeat blood test at a later date. -

NEMO (New England Meow Outfit, Inc.)

N.E.M.O. (New England Meow Outfit, Inc.) wants YOU to come BACK TO THE Bar-B-Q!! th Our 8 CFA Allbreed Championship & Household Pet Cat Show August 28 & 29, 2021 at the Sturbridge Host Hotel in Sturbridge, MA HOTEL SHOW with an OUTDOOR Saturday Night Dinner! Buffet Barbecue on Saturday night $37 (all-inclusive) 5 AB, 3 SP & 8 HHP Rings (EXHIBITOR-ONLY SHOW) Back-to-Back Format NEW 225 Cat Entry Limit Show Photographer – Cindy Pitts-Chenette OUR MASTER CHEFS EARLY BIRD 3 PACK SPECIAL CO -SHOW MANAGER S Judging on Saturday Any 3 entries (same owner) Iris Zinck Pam Bassett - AB & HHP + extra ½ cage space $190 Email [email protected] Jacqui Bennett - SP & HHP Phone: 781-424-1563 Teresa Keiger - AB & HHP Must be paid in full by 7/26/21 Wendy Carson Russell Webb - SP & HHP Email: [email protected] Judging on Sunday FOR THE WELL-BEING OF Phone: 781-826-5425 John Adelhoch - AB CH/PR, SP KIT & HHP CLUBS & PARTICIPANTS VENDOR CONTACT Mary Auth - AB & HHP CFA COVID-19 requirements Donna Wiedemeier Doreann Nasin - AB KIT/PR, SP CH & HHP & CFA recommended COVID-19 Email: [email protected] Sharon Roy - AB CH/KIT, SP PR & HHP general practices will be in effect. Phone: 856-384-2763 Masks STRONGLY RECOMMENDED IN ENTRY FEES THE SHOW HALL. All city, county, state, ENTRY CLERK 1st Entry (includes catalog) $80 $75 and federal COVID-19 and related health Shirley Peet 2nd Entry (same owner) $75 $70 and safety mandates, restrictions and Email: [email protected] 3rd or more Entries (same owner) $70 $65 guidelines in the planning and 415 Shore Dr. -

Chapter 15 VETERINARY PATHOLOGY

Veterinary Pathology Chapter 15 VETERINARY PATHOLOGY ERIC DESOMBRE LOMBARDINI, VMD, MSc, DACVPM, DACVP*; SHANNON HAROLD LACY, DVM, DACVPM, DACVP†; TODD MICHAEL BELL, DVM, DACVP‡; JENNIFER LYNN CHAPMAN, DVM, DACVP§; DARRON A. ALVES, DVM, DACVP¥; and JAMES SCOTT ESTEP, DVM, DACVP¶ INTRODUCTION DIAGNOSTICS BIODEFENSE AND BIOMEDICAL RESEARCH CHEMICAL DEFENSE RADIATION DEFENSE COMBAT CASUALTY CARE FIELD OPERATIONS SUMMARY *Lieutenant Colonel, Veterinary Corps, US Army, Chief, Divisions of Comparative Pathology and Veterinary Medical Research, Armed Forces Research Institute of Medical Sciences, 315/6 Rajavithi Road, Bangkok 10400, Thailand †Major (P), Veterinary Corps, US Army, Chief, Education Operations, Joint Pathology Center, 2460 Linden Lane, Building 161, Room 102, Silver Spring, Maryland 20910 ‡Major (P), Veterinary Corps, US Army, Biodefense Research Pathologist, US Army Medical Research Institute of Infectious Diseases, 1425 Porter Street, Room 901B, Frederick, Maryland 21702 §Lieutenant Colonel, Veterinary Corps, US Army, Director, Overseas Operations, Walter Reed Army Institute of Research, 503 Robert Grant Avenue, Room 1W43, Silver Spring, Maryland 20910 ¥Lieutenant Colonel, Veterinary Corps, US Army, Chief, Operations, US Army Office of the Surgeon General, 7700 Arlington Boulevard, Arlington, Virginia 22042 ¶Lieutenant Colonel, Veterinary Corps, US Army (Retired); formerly, Chief of Comparative Pathology, Triservice Research Laboratory, US Army Institute of Surgical Research, 1210 Stanley Road, Joint Base San Antonio-Fort Sam -

The Role of the Pet-Human Bond: Review and Summary of the Evidence

The role of the pet-human bond Review and summary of the evidence August 2020 The role of the pet-human bond ı Review and summary of the evidence Contents Introduction 4 Summary findings 5 How this evidence review was conducted 6 The structure of this report 6 1. Promoting health and wellbeing across the lifetime 7 1.1. Childhood physical, mental and emotional health and wellbeing 7 1.2. Child educational development 9 1.3. Early adulthood – mental and physical health 10 1.4. Adulthood 11 1.5. Older / later life health and wellbeing 13 1.6. Loneliness and social isolation across the lifetime 16 2. Treatment of degenerative and chronic diseases 19 2.1. Cancer 19 2.2. Cardiovascular disease (CVD) 20 2.3. Atopy, allergies and asthma 21 2.4. Autism spectrum disorder (ASD) 23 2.5. Dementia and Alzheimer’s disease (AD) 23 2.6. Fibromyalgia (pain management) 25 2.7. Impact of animal assisted therapy on wellbeing of therapy dogs 25 2 Contents 3. The role of the bond in building a more inclusive society 26 3.1. People with disabilities (and assistance pets) 26 3.2. Military and service people – post trauma 27 3.3. People in prison, including young offenders and substance misusers 28 3.4. Marginalised and disadvantaged people (including homeless) 28 3.5. Improving social cohesion in cities 29 4. Innovations for health and care technologies and approaches 30 4.1. Animal Assisted Therapy (AAT) 30 4.2. One Health – for obesity prevention 31 5. Wider reflections on the impacts of the pet-human bond and the themes of this review 34 5.1. -

Theriogenology Services

1675 Mollys Backbone Road, Sherrills Ford, NC 28673 Phone 828.478.3500, FAX 828.478.9140, email: [email protected] THERIOGENOLOGY SERVICES PLANNING YOUR BREEDING – WHAT TO EXPECT The entire team at Veterinary Specialties is committed to doing the very best job we can for you to help you achieve your goals. We understand that the breeding you have planned may be the culmination of many years research and coordination. We ask you to trust us in our recommendations for your breeding. Females must be 18 months of age or older to qualify for our ovulation timing services. Get the details organized Please, if you have not already done so, provide us with a copy of your pet’s registration papers. We also need to have signalment of the bitch or dog and the contact information for the “other half of the breeding,” as the case may be. If you are the bitch owner, then we need the dog’s info and the contact information for his owner and the collecting veterinarian. If you are the dog owner, then we need the bitch’s signalment and the bitch owner’s and receiving vet’s contact information. AND we need to know how the breeding will be conducted (vaginal, TCI or surgical insemination) and how many shipments are to be sent. And when we are receiving shipments, we need to get the tracking number for the FedEx or UPS delivery as soon as it becomes available. Be aware that frozen semen shipments take AT LEAST 2 days because a full day is required to charge the shipping container prior to shipping. -

Scratching Resources

AAFP CLAW FRIENDLY EDUCATIONAL TOOLKIT SCRATCHING RESOURCES The best method to advance feline welfare is through education. Many cat caregivers are unaware that scratching is a natu- ral behavior for cats. The AAFP has created the educational resources below to assist your team in educating cat caregivers about why cats need to scratch, ideal scratching surfaces, troubleshooting inappropriate scratching, training cats to scratch appropriately in the home, and alternatives to declawing. Veterinary Professionals Claw Counseling: Helping Clients Live Alongside Cats with Claws (In-depth Article) This comprehensive article provides more detailed information to help you counsel clients on why and how to live with a clawed cat. It provides information about why clients declaw, short and long-term complications, what causes cats to scratch excessively and on unfavorable locations, and how to work through inappropriate scratching situations. See next 7 pages for full size print version. American Association of Feline Practitioners Claw Friendly Educational Toolkit CLAW COUNSELING: Helping clients live alongside cats with claws Submitted by Kelly A. St. Denis, MSc, DVM, DABVP (feline practice) Onychectomy has always been a controversial topic, but over offers onychectomy, open dialogue about this is strongly the last decade, a large push to end this practice has been encouraged. Team members should be mindful that these brought forward by many groups, including major veterinary discussions should be approached with care and respect, for organizations, such as the American Association of Feline themselves and their employer. It is also extremely important Practitioners. As veterinary professionals, we may be asked to include front offce staff in these discussions, as they may about declawing, nail care, and normal scratching behavior in receive direct questions by phone. -

Nova Scotia Veterinary Medical Association Council

G^r? NOVA SCOTIAVETERINARY MEDICAL ASSOCIATION Registrar's Office 15 Cobequid Road, Lower Sackvllle, NS B4C 2M9 Phone: (902) 865-1876 Fax: (902) 865-2001 E-mail: [email protected] September 24, 2018 Dear Chair, and committee members, My name is Dr Melissa Burgoyne. I am a small animal veterinarian and clinic owner in Lower Sackville, Nova Scotia. I am currently serving my 6th year as a member of the NSVMA Council and currently, I am the past president on the Nova Scotia Veterinary Medical Association Council. I am writing today to express our support of Bill 27 and what it represents to support and advocate for those that cannot do so for themselves. As veterinarians, we all went into veterinary medicine because we want to.help animals, prevent and alleviate suffering. We want to reassure the public that veterinarians are humane professionals who are committed to doing what is best for animals, rather than being motivated by financial reasons. We have Dr. Martell-Moran's paper (see attached) related to declawing, which shows that there are significant and negative effects on behavior, as well as chronic pain. His conclusions indicate that feline declaw which is the removal of the distal phalanx, not just the nail, is associated with a significant increase in the odds of adverse behaviors such as biting, aggression, inappropriate elimination and back pain. The CVMA, AAFP, AVMA and Cat Healthy all oppose this procedure. The Cat Fancier's Association decried it 6 years ago. Asfor the other medically unnecessary cosmetic surgeries, I offer the following based on the Mills article.