Development of Small Building Contractors in Botswana; a Critical Evaluation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Inconvenient Indigenous

1 SIDSEL SAUGESTAD The Inconvenient Indigenous Remote Area Development in Botswana, Donor Assistance, and the First People of the Kalahari The Nordic Africa Institute, 2001 2 The book is printed with support from the Norwegian Research Council. Front cover photo: Lokalane – one of the many small groups not recognised as a community in the official scheme of things Back cover photos from top: Irrigation – symbol of objectives and achievements of the RAD programme Children – always a hope for the future John Hardbattle – charismatic first leader of the First People of the Kalahari Ethno-tourism – old dance in new clothing Indexing terms Applied anthropology Bushmen Development programmes Ethnic relations Government policy Indigenous peoples Nation-building NORAD Botswana Kalahari San Photos: The author Language checking: Elaine Almén © The author and The Nordic Africa Institute 2001 ISBN 91-7106-475-3 Printed in Sweden by Centraltryckeriet Åke Svensson AB, Borås 2001 3 My home is in my heart it migrates with me What shall I say brother what shall I say sister They come and ask where is your home they come with papers and say this belongs to nobody this is government land everything belongs to the State What shall I say sister what shall I say brother […] All of this is my home and I carry it in my heart NILS ASLAK VALKEAPÄÄ Trekways of the Wind 1994 ∫ This conference that I see here is something very big. It can be the beginning of something big. I hope it is not the end of something big. ARON JOHANNES at the opening of the Regional San Conference in Gaborone, October 1993 4 Preface and Acknowledgements The title of this book is not a description of the indigenous people of Botswana, it is a characterisation of a prevailing attitude to this group. -

Botswana Semiology Research Centre Project Seismic Stations In

BOTSWANA SEISMOLOGICAL NETWORK ( BSN) STATIONS 19°0'0"E 20°0'0"E 21°0'0"E 22°0'0"E 23°0'0"E 24°0'0"E 25°0'0"E 26°0'0"E 27°0'0"E 28°0'0"E 29°0'0"E 30°0'0"E 1 S 7 " ° 0 0 ' ' 0 0 ° " 7 S 1 KSANE Kasane ! !Kazungula Kasane Forest ReserveLeshomo 1 S Ngoma Bridge ! 8 " ! ° 0 0 ' # !Mabele * . MasuzweSatau ! ! ' 0 ! ! Litaba 0 ° Liamb!ezi Xamshiko Musukub!ili Ivuvwe " 8 ! ! ! !Seriba Kasane Forest Reserve Extension S 1 !Shishikola Siabisso ! ! Ka!taba Safari Camp ! Kachikau ! ! ! ! ! ! Chobe Forest Reserve ! !! ! Karee ! ! ! ! ! Safari Camp Dibejam!a ! ! !! ! ! ! ! X!!AUD! M Kazuma Forest Reserve ! ShongoshongoDugamchaRwelyeHau!xa Marunga Xhauga Safari Camp ! !SLIND Chobe National Park ! Kudixama Diniva Xumoxu Xanekwa Savute ! Mah!orameno! ! ! ! Safari Camp ! Maikaelelo Foreset Reserve Do!betsha ! ! Dibebe Tjiponga Ncamaser!e Hamandozi ! Quecha ! Duma BTLPN ! #Kwiima XanekobaSepupa Khw!a CHOBE DISTRICT *! !! ! Manga !! Mampi ! ! ! Kangara # ! * Gunitsuga!Njova Wazemi ! ! G!unitsuga ! Wazemi !Seronga! !Kaborothoa ! 1 S Sibuyu Forest Reserve 9 " Njou # ° 0 * ! 0 ' !Nxaunxau Esha 12 ' 0 Zara ! ! 0 ° ! ! ! " 9 ! S 1 ! Mababe Quru!be ! ! Esha 1GMARE Xorotsaa ! Gumare ! ! Thale CheracherahaQNGWA ! ! GcangwaKaruwe Danega ! ! Gqose ! DobeQabi *# ! ! ! ! Bate !Mahito Qubi !Mahopa ! Nokaneng # ! Mochabana Shukumukwa * ! ! Nxabe NGAMILAND DISTRICT Sorob!e ! XurueeHabu Sakapane Nxai National Nark !! ! Sepako Caecae 2 ! ! S 0 " Konde Ncwima ° 0 ! MAUN 0 ' ! ! ' 0 Ntabi Tshokatshaa ! 0 ° ! " 0 PHDHD Maposa Mmanxotai S Kaore ! ! Maitengwe 2 ! Tsau Segoro -

2019 GENERAL ELECTIONS REPORT II Keireng A

REPORT TO THE MINISTER FOR PRESIDENTIAL AFFAIRS, GOVERNANCE AND PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION ON THE 2019 GENERAL ELECTIONS 2019 GENERAL ELECTIONS I REPORT Honourable Justice Abednego B. Tafa Mr. John Carr-Hartley Members of CHAIRMAN DEPUTY CHAIRMAN The Independent Electoral Commission Mrs. Agnes Setlhogile Mrs. Shaboyo Motsamai Dr. Molefe Phirinyane COMMISSIONER COMMISSIONER COMMISSIONER Mrs. Martha J. Sayed Vacant COMMISSIONER COMMISSIONER 2019 GENERAL ELECTIONS REPORT II Keireng A. Zuze Doreen L. Serumula SECRETARY DEPUTY SECRETARY Executive Management of the Secretariat Keolebogile M. Tshitlho Dintle S. Rapoo SENIOR MANAGER MANAGER CORPORATE SERVICES ELECTIONS AFFAIRS & FIELD OPERATIONS Obakeng B. Tlhaodi Uwoga H. Mandiwana CHIEF STATE COUNSEL MANAGER HUMAN RESOURCE & ADMINISTRATION 2019 GENERAL ELECTIONS REPORT III Strategic Foundations ........................................................................................................................... I Members of The Independent Electoral Commission ................................................ II Executive Management of the Secretariat........................................................................... III Letter to The Minister for Presidential Affairs, Governance and Public Administration ............................................................................................................... 1 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS.................................................................................................................. 2 ACRONYMS ............................................................................................................................................... -

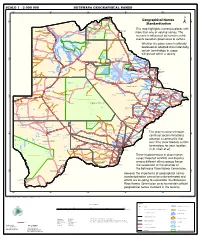

Geographical Names Standardization BOTSWANA GEOGRAPHICAL

SCALE 1 : 2 000 000 BOTSWANA GEOGRAPHICAL NAMES 20°0'0"E 22°0'0"E 24°0'0"E 26°0'0"E 28°0'0"E Kasane e ! ob Ch S Ngoma Bridge S " ! " 0 0 ' ' 0 0 ° Geographical Names ° ! 8 !( 8 1 ! 1 Parakarungu/ Kavimba ti Mbalakalungu ! ± n !( a Kakulwane Pan y K n Ga-Sekao/Kachikaubwe/Kachikabwe Standardization w e a L i/ n d d n o a y ba ! in m Shakawe Ngarange L ! zu ! !(Ghoha/Gcoha Gate we !(! Ng Samochema/Samochima Mpandamatenga/ This map highlights numerous places with Savute/Savuti Chobe National Park !(! Pandamatenga O Gudigwa te ! ! k Savu !( !( a ! v Nxamasere/Ncamasere a n a CHOBE DISTRICT more than one or varying names. The g Zweizwe Pan o an uiq !(! ag ! Sepupa/Sepopa Seronga M ! Savute Marsh Tsodilo !(! Gonutsuga/Gonitsuga scenario is influenced by human-centric Xau dum Nxauxau/Nxaunxau !(! ! Etsha 13 Jao! events based on governance or culture. achira Moan i e a h hw a k K g o n B Cakanaca/Xakanaka Mababe Ta ! u o N r o Moremi Wildlife Reserve Whether the place name is officially X a u ! G Gumare o d o l u OKAVANGO DELTA m m o e ! ti g Sankuyo o bestowed or adopted circumstantially, Qangwa g ! o !(! M Xaxaba/Cacaba B certain terminology in usage Nokaneng ! o r o Nxai National ! e Park n Shorobe a e k n will prevail within a society a Xaxa/Caecae/Xaixai m l e ! C u a n !( a d m a e a a b S c b K h i S " a " e a u T z 0 d ih n D 0 ' u ' m w NGAMILAND DISTRICT y ! Nxai Pan 0 m Tsokotshaa/Tsokatshaa 0 Gcwihabadu C T e Maun ° r ° h e ! 0 0 Ghwihaba/ ! a !( o 2 !( i ata Mmanxotae/Manxotae 2 g Botet N ! Gcwihaba e !( ! Nxharaga/Nxaraga !(! Maitengwe -

Republic of Botswana the Project for Enhancing National Forest Monitoring System for the Promotion of Sustainable Natural Resource Management

DEPARTMENT OF FORESTRY AND RANGE RESOURCES (DFRR) MINISTRY OF ENVIRONMENT, NATURAL RESOURCES CONSERVATION AND TOURISM (MENT) REPUBLIC OF BOTSWANA REPUBLIC OF BOTSWANA THE PROJECT FOR ENHANCING NATIONAL FOREST MONITORING SYSTEM FOR THE PROMOTION OF SUSTAINABLE NATURAL RESOURCE MANAGEMENT PROJECT COMPLETION REPORT DECEMBER 2017 JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY(JICA) ORIENTAL CONSULTANTS GLOBAL CO., LTD. JAPAN FOREST TECHNOLOGY ASSOCIATION GE JR 17-131 DEPARTMENT OF FORESTRY AND RANGE RESOURCES (DFRR) MINISTRY OF ENVIRONMENT, NATURAL RESOURCES CONSERVATION AND TOURISM (MENT) REPUBLIC OF BOTSWANA REPUBLIC OF BOTSWANA THE PROJECT FOR ENHANCING NATIONAL FOREST MONITORING SYSTEM FOR THE PROMOTION OF SUSTAINABLE NATURAL RESOURCE MANAGEMENT PROJECT COMPLETION REPORT DECEMBER 2017 JAPAN INTERNATIONAL COOPERATION AGENCY(JICA) ORIENTAL CONSULTANTS GLOBAL CO., LTD. JAPAN FOREST TECHNOLOGY ASSOCIATION DFRR/JICA: Botswana Forest Distribution Map Zambia Angola Zambia Legend KASANE Angola ! ! Settlement CountryBoundary Riparian Forest Typical Forest Woodland Zimbabwe Zimbabwe Bushland/Shrubland Savanna/Grassland/Forbs MAUN ! NATA Baregorund ! TUTUME ! Desert/Sand Dunes Marsh/Wetland FRANCISTOWN Waterbody/Pan ! ORAPA Namibia ! TONOTA ! GHANZI Angola Zambia Namibia ! SELEBI-PHIKWE BOBONONG ! ! Zimbabwe SEROWE ! PALAPYE ! Namibia MAHALAPYE ! South Africa KANG ! MOLEPOLOLE MOCHUDI ! ! JWANENG ! GABORONE ! ´ 0 50 100 200 RAMOTSWA ! KANYE Kilometres ! Coordinate System: GCS WGS 1984 Datum: WGS 1984 LOBATSE ! Botswana Forest Distribution Map Produced from -

Ecosystem-Based Adaptation and Mitigation in Botswana's Communal

Ecosystem-Based Adaptation and Mitigation in Botswana’s Communal Rangelands ANNEX 6: Environmental and Social Impact Assessment (ESIA) and Environmental and Social Management Plan (ESMP) Prepared by Conservation International and C4 EcoSolutions through a PPF grant from the Green Climate Fund ESIA and ESMP Table of Contents 1. Executive summary .................................................................................................... 4 2. Introduction............................................................................................................... 9 3. Project Description .................................................................................................. 10 3.1. Strengthening community institutions and gender equitable capacity for collective action 11 3.2. Building individual capacity in herders and the community .......................................... 12 3.3. Supporting climate smart land and livestock management ........................................... 13 3.4. Strengthening mitigation & adaptive capacity across the value-chain for long-term sustainability.......................................................................................................................... 14 3.5. Knowledge sharing and mechanisms for continual improvement and replication .......... 15 4. Policy, legal and administrative framework ............................................................. 16 4.1. Governance, decentralisation and resource management instruments ......................... 16 4.2. Environmental -

Botswana Power Corporation

BPC Accelerated Green Energy Initiative BOTSWANA POWER CORPORATION TENDER NO. 2273/17 REQUEST FOR PROPOSAL RELATING TO THE DEVELOPMENT, FINANCING, CONSTRUCTION, OPERATION AND MAINTENANCE OF 12 SOLAR PHOTOVOLTAIC POWER PROJECTS PART I GENERAL INSTRUCTIONS TO BIDDER ISSUE DATE: 26TH NOVEMBER 2018 BPC Re-tender No. 2273/17 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS .......................................................................................................................... 2 PART I ..................................................................................................................................................... 2 GENERAL INSTRUCTIONS TO BIDDER ............................................................................................... 2 1. Introduction ....................................................................................................................................... 2 2. Project Information & Concept ......................................................................................................... 8 3. Bidding Process & Form of Bids .................................................................................................... 10 4. Instructions to Bidders (Volume 1 – Part I Compliance & Qualifications) ...................................... 20 5. Instruction to Bidders (Volume 1 – Part I Technical & Financial Proposals).................................. 22 ANNEX 1 .............................................................................................................................................. -

'Improving Their Lives.' State Policies and San Resistance in Botswana

Western University Scholarship@Western Aboriginal Policy Research Consortium International (APRCi) 2005 ‘Improving their lives.’ State policies and San resistance in Botswana Sidsel Saugestad Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/aprci Part of the Human Rights Law Commons, and the Other Public Affairs, Public Policy and Public Administration Commons Citation of this paper: Saugestad, Sidsel, "‘Improving their lives.’ State policies and San resistance in Botswana" (2005). Aboriginal Policy Research Consortium International (APRCi). 191. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/aprci/191 ‘Improving their lives.’ State policies and San resistance in Botswana Sidsel Saugestad Department of Social Anthropology, University of Tromso, N- 9037, Tromsø, Norway [email protected] Keywords San, Botswana, game reserve, relocation, indigenous peoples, land claim Abstract A court case raised by a group of San (former) hunter-gatherers, protesting against relocation from the Central Kalahari Game Reserve, has attracted considerable international attention. The Government of Botswana argues that the relocation was done in order to ‘improve the lives’ of the residents, and that it was in their own best interest. The residents plead their right to stay in their traditional territories, a right increasingly acknowledged in international law, and claim that they did not relocate voluntarily. The case started in 2004 and will, due to long interspersed adjournments, go on into 2006. This article traces the events that led up to the case, and reports on its progress thus far. The case is seen as an arena for expressing and negotiating the relationship between an indigenous minority and the state in which they reside. -

Public Primary Schools

PRIMARY SCHOOLS CENTRAL REGION NO SCHOOL ADDRESS LOCATION TELE PHONE REGION 1 Agosi Box 378 Bobonong 2619596 Central 2 Baipidi Box 315 Maun Makalamabedi 6868016 Central 3 Bobonong Box 48 Bobonong 2619207 Central 4 Boipuso Box 124 Palapye 4620280 Central 5 Boitshoko Bag 002B Selibe Phikwe 2600345 Central 6 Boitumelo Bag 11286 Selibe Phikwe 2600004 Central 7 Bonwapitse Box 912 Mahalapye Bonwapitse 4740037 Central 8 Borakanelo Box 168 Maunatlala 4917344 Central 9 Borolong Box 10014 Tatitown Borolong 2410060 Central 10 Borotsi Box 136 Bobonong 2619208 Central 11 Boswelakgomo Bag 0058 Selibe Phikwe 2600346 Central 12 Botshabelo Bag 001B Selibe Phikwe 2600003 Central 13 Busang I Memorial Box 47 Tsetsebye 2616144 Central 14 Chadibe Box 7 Sefhare 4640224 Central 15 Chakaloba Bag 23 Palapye 4928405 Central 16 Changate Box 77 Nkange Changate Central 17 Dagwi Box 30 Maitengwe Dagwi Central 18 Diloro Box 144 Maokatumo Diloro 4958438 Central 19 Dimajwe Box 30M Dimajwe Central 20 Dinokwane Bag RS 3 Serowe 4631473 Central 21 Dovedale Bag 5 Mahalapye Dovedale Central 22 Dukwi Box 473 Francistown Dukwi 2981258 Central 23 Etsile Majashango Box 170 Rakops Tsienyane 2975155 Central 24 Flowertown Box 14 Mahalapye 4611234 Central 25 Foley Itireleng Box 161 Tonota Foley Central 26 Frederick Maherero Box 269 Mahalapye 4610438 Central 27 Gasebalwe Box 79 Gweta 6212385 Central 28 Gobojango Box 15 Kobojango 2645346 Central 29 Gojwane Box 11 Serule Gojwane Central 30 Goo - Sekgweng Bag 29 Palapye Goo-Sekgweng 4918380 Central 31 Goo-Tau Bag 84 Palapye Goo - Tau 4950117 -

Daily Hansard 16 March 2021

DAILY YOUR VOICE IN PARLIAMENT THE SECONDSECOND MEETING MEETING OF THEOF SECONDTHE FIFTH SESSION SESSION OF THEOF THEELEVEN TWELFTHTH PARLIAMENT PARLIAMENT TUESDAY 16 MARCH 2021 MIXEDENGLISH VERSION VERSION HANSARDHANSARD NO. 193201 DISCLAIMER Unocial Hansard This transcript of Parliamentary proceedings is an unocial version of the Hansard and may contain inaccuracies. It is hereby published for general purposes only. The nal edited version of the Hansard will be published when available and can be obtained from the Assistant Clerk (Editorial). THE NATIONAL ASSEMBLY SPEAKER The Hon. Phandu T. C. Skelemani PH, MP. DEPUTY SPEAKER The Hon. Mabuse M. Pule, MP. (Mochudi East) Clerk of the National Assembly - Ms B. N. Dithapo Deputy Clerk of the National Assembly - Mr L. T. Gaolaolwe Learned Parliamentary Counsel - Ms M. Mokgosi Assistant Clerk (E) - Mr R. Josiah CABINET His Excellency Dr M. E. K. Masisi, MP. - President His Honour S. Tsogwane, MP. (Boteti West) - Vice President Minister for Presidential Affairs, Governance and Public Hon. K. N. S. Morwaeng, MP. (Molepolole South) - Administration Hon. K. T. Mmusi, MP. (Gabane-Mmankgodi) - Minister of Defence, Justice and Security Hon. Dr L. Kwape, MP. (Kanye South) - Minister of International Affairs and Cooperation Hon. E. M. Molale, MP. (Goodhope-Mabule ) - Minister of Local Government and Rural Development Hon. K. S. Gare, MP. (Moshupa-Manyana) - Minister of Agricultural Development and Food Security Minister of Environment, Natural Resources Conservation Hon. P. K. Kereng, MP. (Specially Elected) - and Tourism Hon. Dr E. G. Dikoloti MP. (Mmathethe-Molapowabojang) - Minister of Health and Wellness Hon. T.M. Segokgo, MP. (Tlokweng) - Minister of Transport and Communications Hon. -

Evaluation of the Vulnerable Grouped Feeding Programme

Evaluation of the Vulnerable Groups Feeding Programme Commissioned by UNICEF 18 August 2019 Prepared by Mokoro Ltd. in association with Evaluation of the Vulnerable Groups Feeding Programme __________________________________________________________________________________ Disclaimer The designations employed, maps and the presentation of the material in this document do not imply the expression of any opinion whatsoever on the part of the Government of Botswana or the United Nations Children’s Fund concerning the legal status of any country, territory, city or area, or of its authorities, or concerning the delineation of its frontiers or boundaries. Evaluation team Christine Fenning Evaluator and Research Co-ordinator Alta Fölscher Senior Evaluator Elizabeth Hodson Economist Jane Keylock Nutritionist Dolly Ntseane Evaluator and National Research Co-ordinator Molefe Phirinyane Social Policy Adviser Stephen Turner Evaluation Team Leader Matthew Smith Quality Support Muriel Visser Quality Support BIDPA field survey team Tefo Bosilong Godiraone Modirwagale Supervisor Shepard Diamango Supervisor Mmereki Mokgethe Mautleo Goitsemodimo Katlego Molefe Seele Goleanye Pako Mowaneng Supervisor Ontlametse Kebabope Kamogelo Nkile Supervisor Singo Kediseng Thatayaone Patikego Bame Kesetse Maitumelo Ramonkga Supervisor Kagiso Lefitile Olerato Sumbolu Portia Malele Supervisor Gosiame Tshegetsang ___________________________________________________________________________ ii Evaluation of the Vulnerable Groups Feeding Programme __________________________________________________________________________________ Preface The welfare and prosperity of Botswana depend on the good nutrition of its children. Stunting continues to afflict too many of those children, and is a matter of national concern. The first ever evaluation of the Vulnerable Groups Feeding Programme – to assess its performance in reducing stunting – is therefore an important task. Mokoro Limited and the Botswana Institute for Development Policy Analysis were privileged to be commissioned to carry out this evaluation. -

CITIES/TOWNS and VILLAGES Projections 2020

CITIES/TOWNS AND VILLAGES Projections 2020 Private Bag 0024, Gaborone Tel: 3671300 Fax: 3952201 Toll Free: 0800 600 200 Private Bag F193, City of Francistown Botswana Tel. 241 5848, Fax. 241 7540 Private Bag 32 Ghanzi Tel: 371 5723 Fax: 659 7506 Private Bag 47 Maun Tel: 371 5716 Fax: 686 4327 E-mail: [email protected] Website: http://www.statsbots.org.bw Cities/Towns And Villages Projections 2020 Published by Statistics Botswana Private Bag 0024, Gaborone Website: www.statsbots.org.bw E-mail: [email protected] Contact: Census and Demography Analysis Unit Tel: (267) 3671300 Fax: (267) 3952201 November, 2020 COPYRIGHT RESERVED Extracts may be published if source Is duly acknowledged Cities/Towns and Villages Projections 2020 Preface This stats brief provides population projections for the year 2020. In this stats brief, the reference point of the population projections was the 2011 Population and Housing Census, in which the total population by age and sex is available. Population projections give a picture of what the future size and structure of the population by sex and age might look like. It is based on knowledge of the past trends, and, for the future, on assumptions made for three components of population change being fertility, mortality and migration. The projections are derived from mathematical formulas that use current populations and rates of growth to estimate future populations. The population projections presented is for Cities, Towns and Villages excluding associated localities for the year 2020. Generally, population projections are more accurate for large populations than for small populations and are more accurate for the near future than the distant future.