Ecosystem-Based Adaptation and Mitigation in Botswana's Communal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

![Botswana. Delimitation Commission. [Report Of] Delimitation Commission 1972](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/5626/botswana-delimitation-commission-report-of-delimitation-commission-1972-45626.webp)

Botswana. Delimitation Commission. [Report Of] Delimitation Commission 1972

Botswana. Delimitation Commission. [Report of] Delimitation Commission 1972. Gaborone, Government Pointer [1972?] 16p. 3 fold, maps in pocket at end. 29icm. 1. Botswana-Boundaries, Internal. DELIMITATION COMMISSION 1972 His Excellency Sir Seretse Khama, K.B.E., President of the Republic of Botswana. Your Excellency, We, the undersigned, having been appointed by the Judicial Service Commission to hold a Delimitation Commission under the provisions of Section 65 (1) of the Botswana Constitution, and such appointment having been published in the Government Notice No. 292 of 1972 on the Thirteenth Day of October, 1972 have the honour to inform Your Excellency that we have carried out the said Commission and we append hereto our. Report. (Sir Peter Watkin Williams) Chairman. ,(Rev. A.G. Kgasa) (Father B. Setlalekgosi) Member. Member. (M.J. Pilane) (S.T. Khama) Member. Member. GABORONE, Botswana. The'1st Day of November, 1972. REPORT OF THE DELIMITATION COMMISSION 1972 ~ « .. 1 th ye ar 19 4 cl,mitation - - ? ® L ® ^'p 'Commission was appointed under the provisions of Section 3 of the Bechuanaland (Electoral Provisions) Order-ln-Council of 1964 and this Commission . then proceeded to;divide the country up into thirty-one Constituencies. This Commission was enjoined, as we, ourselves, are similarly enjoined, to base the delimitation of the Constituencies primarily on the number of inhabitants of the. country, but also taking account of natural community of interst, means of communication, geographical features, the density of population and the boundaries of tribal territories and administrative districts. This Commission created thirty-one Constituencies with populations all of which were reasonably cWe to the population quote, that is to say the total population of the country divided by the number of constituencies; the greatest variation being only 18.7% This is assuming that the Census which had taken place shortly before the Commission sat had arrived at a reasonably accurate assessment of the population in each district. -

Botswana Demand, Supply, Policy and Regulation Diagnostic Report 2015

Making Access Possible BWP Botswana Demand, Supply, Policy and Regulation Diagnostic Report 2015 Table of Contents Table of Contents ............................................................................................................. i List of Figures ................................................................................................................. iv List of Tables ..................................................................................................................vii List of Acronyms and Abbreviations ................................................................................ ix Executive Summary ....................................................................................................... xiv Introduction ......................................................................................................................... xiv Analysing financial inclusion in Botswana ........................................................................... xiv Context drives scope for market development .......................................................... xiv Regulatory framework and financial inclusion ............................................................ xv Current usage of financial services .............................................................................. xv Priority target markets needs ..................................................................................... xvi Small but diverse provider landscape ....................................................................... -

WELLFIELD ·I I

"~), ~ ',0 )/)'./ iiJ G./) / .,' it-3~" - - ' REPUBLIC OF BOTSWANA DEPARTMENT OF GEOLOGICAL SURVEY MATSHENG AREA GROUNDWATER INVESTIGATION (TB 10/2/12/92-93) DRAFT TECHNICAL REPORT T9: SOCIO-ECONOMIC IMPACT ASSESSMENT AUGUST 1995 Prepared by = ~.-~~.. INTER WELLFIELD ·i i,.. CO'ISULT in association with BRITISH GEOLOGICAL SURVEY Keyworth, Nottingham, UK MATSHENG AREA GROUNDWATER INVESTIGATION Technical Report T9 August 1995 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 1. Usable potable water supplies are limited to the Matsheng village areas. Economic fresh water supplies identified during recent groundwater investigations are located in village areas of Lokgwabe and Lehututu. Brackish water supplies identified outside the village areas are not available for use by livestock using communal grazing areas as they are either in areas already occupied or in areas with other land use designations. 2. No significant usable water supplies were identified in the communal grazing areas through the MAGI programme, and based on the available geophysical evidence, the chances of striking groundwater supplies for livestock in Matsheng communal areas are poor. 3. Total water consumption in the Matsheng area during the past year (to May 1995) is estimated at 254,200m' (697 m' per day). Of this amount about 150,000 m' (60%) are consumed by livestock watered at about 150 wells, boreholes and dams on pans. 4. Matsheng village households using public standpipes consume about 670 litres per household per week, or 20 litres per person per day (67% of the 30 litre DWA standard rate for rural village standpipe users). Residents of the four RAD settlements served by council bowsers received a ration of about 7 litres per person per day, or just 23% of the DWA standard. -

Performance of Goats and Sheep Under Communal Grazing in Botswana Using Various Growth Measures

B07 Performance of goats and sheep under communal grazing in Botswana using various growth measures L. Baleseng, O. E Kgosikoma, A. Makgekgenene | Department of Agricultural Research, Private | Gaborone | Botswana M. Coleman, P. Morley | Institute for Rural Futures, School of Behavioural, Cognitive and Social Sciences, University of New England | Armidale | Australia D. Baker, O. | UNE Business School, University of New England | Armidale | Australia S. Bahta | International Livestock Research Institute | Nairobi | Kenya DOI: 10.1481/icasVII.2016.b07 ABSTRACT We conducted a survey to evaluate the growth of goats and sheep under communal grazing, and to determine the relationship between weight, heart girth, shoulder height, and body condition score in Kweneng, Central and Kgalagadi districts, Botswana. The same animals were measured on two separate occasions, approximately one month apart, to allow growth rates to be recorded. Significant differences in growth rates between the three case study districts were found for both goats and sheep. Amongst the goats measured, gains in height and weight were significantly greater in the Kweneng district, while gains in heart girth measurement were greatest in the Central district. In the case of sheep, weight gain was significantly higher in the Central and Kgalagadi districts, increases in girth measurement were significantly higher in the Central district, and shoulder height gain was significantly greater in the Kweneng district. Statistical tests were used to determine the relationships between animal weight and the other measures taken for goats and sheep. Heart girth in both goats and sheep was shown to be a significant predictor of weight across all three districts. Likewise, shoulder height proved to be a statistically significant predictor of animal weight for both goats and sheep, across each district. -

GOVERNMENT of BOTSWANA/UNFPA 5Th COUNTRY PROGRAMME 2010-2016

25 September 2015 GOVERNMENT OF BOTSWANA/UNFPA 5th COUNTRY PROGRAMME 2010-2016 End of Programme Evaluation i Map of Botswana Consultant Team Position and Team Role Name Team Leader, plus Gender Component Helen Jackson Reproductive Health and Rights Component Thabo Phologolo Population and Development Component Enock Ngome ii Acknowledgements The evaluation team would like to thank UNFPA for the opportunity to undertake the GoB/UNFPA 5th Country Programme Evaluation. We would also like to express our great appreciation to all staff who gave generously of their time, both for interview and in providing documents, and in particular the evaluation manager. We greatly appreciate their support and guidance throughout and would also like to acknowledge the very helpful logistics support by administrative staff including the drivers. We also wish to express our gratitude to the members of the Evaluation Reference Group and to the many stakeholders in government, the UN and civil society for their flexibility and willingness to contribute their views, provide further documents, and generally assist the evaluation. The regional office, ESARO is acknowledged for financial and technical support for the evaluation. Last but not least, we appreciate the beneficiaries that we were able to meet who provided valuable insights into the programmes and how they had impacted on their lives. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS .................................................................................................................................. -

Measuring Social Vulnerability to Natural Hazards at the District Level in Botswana

Jàmbá - Journal of Disaster Risk Studies ISSN: (Online) 2072-845X, (Print) 1996-1421 Page 1 of 11 Original Research Measuring social vulnerability to natural hazards at the district level in Botswana Authors: Social vulnerability to natural hazards has become a topical issue in the face of climate change. 1,2 Kakanyo F. Dintwa For disaster risk reduction strategies to be effective, prior assessments of social vulnerability Gobopamang Letamo2 Kannan Navaneetham2 have to be undertaken. This study applies the household social vulnerability methodology to measure social vulnerability to natural hazards in Botswana. A total of 11 indicators were Affiliations: used to develop the District Social Vulnerability Index (DSVI). Literature informed the 1 Environment Statistics Unit, selection of indicators constituting the model. The principal component analysis (PCA) Statistics Botswana, Gaborone, Botswana method was used to calculate indicators’ weights. The results of this study reveal that social vulnerability is mainly driven by size of household, disability, level of education, age, people 2Department of Population receiving social security, employment status, households status and levels of poverty, in that Studies, University of order. The spatial distribution of DSVI scores shows that Ngamiland West, Kweneng West Botswana, Gaborone, and Central Tutume are highly socially vulnerable. A correlation analysis was run between Botswana DSVI scores and the number of households affected by floods, showing a positive linear Corresponding author: correlation. The government, non-governmental organisations and the private sector should Kakanyo Dintwa, appreciate that social vulnerability is differentiated, and intervention programmes should [email protected] take cognisance of this. Dates: Keywords: Botswana; District Social Vulnerability; place vulnerability; natural hazards; Received: 21 Feb. -

Spatial Analysis of HIV Infection and Associated Risk Factors in Botswana

International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health Article Spatial Analysis of HIV Infection and Associated Risk Factors in Botswana Malebogo Solomon *, Luis Furuya-Kanamori and Kinley Wangdi Department of Global Health, Research School of Population Health, Australian National University, Canberra, ACT 2601, Australia; [email protected] (L.F.-K.); [email protected] (K.W.) * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Botswana has the third highest human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) prevalence globally, and the severity of the epidemic within the country varies considerably between the districts. This study aimed to identify clusters of HIV and associated factors among adults in Botswana. Data from the Botswana Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome (AIDS) Impact Survey IV (BIAS IV), a nationally representative household-based survey, were used for this study. Multivariable logistic regression and Kulldorf’s scan statistics were used to identify the risk factors and HIV clusters. Socio-demographic characteristics were compared within and outside the clusters. HIV prevalence among the study participants was 25.1% (95% CI 23.3–26.4). HIV infection was significantly higher among the female gender, those older than 24 years and those reporting the use of condoms, while tertiary education had a protective effect. Two significant HIV clusters were identified, one located between Selibe-Phikwe and Francistown and another in the Central Mahalapye district. Clusters had higher levels of unemployment, less people with tertiary education and more people residing in rural areas compared to regions outside the clusters. Our study identified high-risk populations and regions with a high burden of HIV infection in Botswana. -

Botswana Environment Statistics Water Digest 2018

Botswana Environment Statistics Water Digest 2018 Private Bag 0024 Gaborone TOLL FREE NUMBER: 0800600200 Tel: ( +267) 367 1300 Fax: ( +267) 395 2201 E-mail: [email protected] Website: http://www.statsbots.org.bw Published by STATISTICS BOTSWANA Private Bag 0024, Gaborone Phone: 3671300 Fax: 3952201 Email: [email protected] Website: www.statsbots.org.bw Contact Unit: Environment Statistics Unit Phone: 367 1300 ISBN: 978-99968-482-3-0 (e-book) Copyright © Statistics Botswana 2020 No part of this information shall be reproduced, stored in a Retrieval system, or even transmitted in any form or by any means, whether electronically, mechanically, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of Statistics Botswana. BOTSWANA ENVIRONMENT STATISTICS WATER DIGEST 2018 Statistics Botswana PREFACE This is Statistics Botswana’s annual Botswana Environment Statistics: Water Digest. It is the first solely water statistics annual digest. This Digest will provide data for use by decision-makers in water management and development and provide tools for the monitoring of trends in water statistics. The indicators in this report cover data on dam levels, water production, billed water consumption, non-revenue water, and water supplied to mines. It is envisaged that coverage of indicators will be expanded as more data becomes available. International standards and guidelines were followed in the compilation of this report. The United Nations Framework for the Development of Environment Statistics (UNFDES) and the United Nations International Recommendations for Water Statistics were particularly useful guidelines. The data collected herein will feed into the UN System of Environmental Economic Accounting (SEEA) for water and hence facilitate an informed management of water resources. -

Environmental Mitigation and Monitoring Plan (Emmp)

ENVIRONMENTAL MITIGATION AND MONITORING PLAN (EMMP) Project/activity, Organizational/administrative, and Environmental Compliance Data Project/Activity Data Project/Activity Name: Feed the Future Senegal Nafoore Warsaaji Geographic Location(s) (Country/Region): Senegal/West Africa Implementation Start/End Dates: March 11, 2020- March 11, 2023 Contract/Award Number: SBAR-CPFF-72068520C00001 Implementing Partner(s): Connexus Corporation Tracking ID: Tracking ID/link of Related IEE: Tracking ID/link of Other, Related Analyses: Organizational/Administrative Data Implementing Operating Unit(s): (e.g. Mission or Bureau or Office) Lead BEO Bureau: Prepared by: Date Prepared: Submitted by: Date Submitted: Environmental Compliance Review Data Analysis Type: EMMP Additional Analyses/Reporting Required: EMMR Purpose Environmental Mitigation and Monitoring Plans (EMMPs) are required for USAID-funded projects, as specified in ADS 204, when the 22 CFR 216 documentation governing the project (e.g. the Initial Environmental Examination (IEE) specifies mitigation measures are needed. EMMPs are in important tool for translating applicable IEE conditions and mitigation measures into specific, implementable, and verifiable actions. FEED THE FUTURE SENEGAL NAFOORE WARSAAJI EMMP i An EMMP is an action plan that clearly defines: 1. Mitigation measures. Actions that reduce or eliminate potential negative environmental impacts resulting directly or indirectly from a particular project or activity, including environmental limiting factors that constrain development. 2. EMMP monitoring indicators.1 Criteria that demonstrate whether mitigation measures are suitable and implemented effectively. 3. Monitoring/reporting frequency. Timeframes for appropriately monitoring the effectiveness of each specific action. 4. Responsible parties. Appropriate, knowledgeable positions assigned to each specific action. 5. Field Monitoring/Issues. Field monitoring needs to be adequately addressed i.e. -

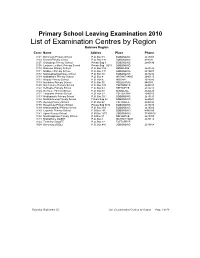

List of Examination Centres by Region Bobirwa Region Centr Name Addres Place Phone 0101 Bobonong Primary School P.O

Primary School Leaving Examination 2010 List of Examination Centres by Region Bobirwa Region Centr Name Addres Place Phone 0101 Bobonong Primary School P.O. Box 48 BOBONONG 2619207 0103 Borotsi Primary School P.O. Box 136 BOBONONG 819208 0107 Gobojango Primary School Private Bag 8 BOBONONG 2645436 0108 Lentswe-Le-Moriti Primary School Private Bag 0019 BOBONONG 0110 Mabolwe Primary School P.O. Box 182 SEMOLALE 2645422 0111 Madikwe Primary School P.O. Box 131 BOBONONG 2619221 0112 Mafetsakgang primary school P.O. Box 46 BOBONONG 2619232 0114 Mathathane Primary School P.O. Box 4 MATHATHANE 2645110 0117 Mogapi Primary School P.O. Box 6 MOGAPI 2618545 0119 Molalatau Primary School P.O. Box 50 MOLALATAU 845374 0120 Moletemane Primary School P.O. Box 176 TSETSEBYE 2646035 0123 Sefhophe Primary School P.O. Box 41 SEFHOPHE 2618210 0124 Semolale Primary School P.O. Box 10 SEMOLALE 2645422 0131 Tsetsejwe Primary School P.O. Box 33 TSETSEJWE 2646103 0133 Modisaotsile Primary School P.O. Box 591 BOBONONG 2619123 0134 Motlhabaneng Primary School Private Bag 20 BOBONONG 2645541 0135 Busang Primary School P.O. Box 47 TSETSEBJE 2646144 0138 Rasetimela Primary School Private Bag 0014 BOBONONG 2619485 0139 Mabumahibidu Primary School P.O. Box 168 BOBONONG 2619040 0140 Lepokole Primary School P O Box 148 BOBONONG 4900035 0141 Agosi Primary School P O Box 1673 BOBONONG 71868614 0142 Motsholapheko Primary School P O Box 37 SEFHOPHE 2618305 0143 Mathathane DOSET P.O. Box 4 MATHATHANE 2645110 0144 Tsetsebye DOSET P.O. Box 33 TSETSEBYE 3024 Bobonong DOSET P.O. Box 483 BOBONONG 2619164 Saturday, September 25, List of Examination Centres by Region Page 1 of 39 Boteti Region Centr Name Addres Place Phone 0201 Adult Education Private Bag 1 ORAPA 0202 Baipidi Primary School P.O. -

Bakgomong: the Babirwa's Transboundarypastoralist Identity

New Contree, No. 75, July 2016, Bakgomong Bakgomong: The Babirwa’s transboundary pastoralist identity and social change in late 19th century Botswana Phuthego Molosiwa Botswana College of Open and Distance Learning [email protected] Abstract To follow is a critical narrative on the intersection between identity production and transformations in the indigenous herding systems of the Babirwa of pre-colonial Botswana. The production of the Babirwa’s pastoralist identity rested on the adaptability of their cultural practices, language and social systems to socio-ecological influences. This emerging pastoralist identity was embedded in organic or loan words and concepts, which were continually reconstituted to negotiate social and environmental change. From the 1850s, the Babirwa of the eastern Botswana gradually transformed into cattle herders. The assimilation of cattle led to a symbolic shift in the Babirwa’s social identity from the Banareng (people of the buffalo) to theBakgomong (people of the cow). This shift was crucial in the production of a cattle-based identity in an area where crop production, hunting and the herding of caprines (goats and sheep) had been the primary ways of life since the first settlement of the Babirwa in the eastern Botswana a century earlier. Keywords: Bakgomong; Botswana; Babirwa; Cattle; Identity; Environment; Power; Cultural Encounters; Social change. Introduction Ee kgomo (yes cow)! goes the Babirwa’s acknowledgement of one another. The Babirwa praise each other as kgomo, referring to their totem, the nare (buffalo), which to them iskgomo ya naga, “a wild cow”.1 Since the Babirwa had knowledge that buffaloes were wild cattle, this praise phrase may have roots in their adoption of the buffalo totemic identity long before the mid- century while they lived in Nareng (place of buffalo) in the Transvaal.2 From the 1850s, the Babirwa, on the confluence of the Limpopo and Shashe rivers 1 The language of the Babirwa is called Sebirwa. -

Bots Ult Aug 20 Itin

Ultimate Botswana With Naturalist Journeys & Caligo Ventures Ultimate Botswana August 10 – 24, 2020 866.900.1146 800.426.7781 520.558.1146 [email protected] www.naturalistjourneys.com or find us on Facebook at Naturalist Journeys, LLC Naturalist Journeys, LLC | Caligo Ventures PO Box 16545 Portal, AZ 85632 PH: 520.558.1146 | 866.900.1146 Fax 650.471.7667 naturalistjourneys.com | caligo.com [email protected] | [email protected] Embark on a true African safari to Botswana, where Tour Highlights the wildlife is pristine and our days are timed with ü the rhythm of nature. Botswana is visually Explore the Okavango Delta’s papyrus-lined exciting—each of its unique habitats have distinct channels and lagoons, the teak woodlands of features, most famous of which is the Okavango Kasane, extensive wetlands and Moremi’s Delta. This tour is limited to just nine participants Mopane forests ü traveling with local experts and Naturalist Journeys’ Hone your photo and wildlife-spotting skills daily Greg Smith. on drives and boat trips in Chobe National Park with a naturalist and photo guide. ü We call this one “ultimate,” not for contrived Look for Leopard, often seen in Chobe National creature comforts but for the amazing opportunity Park ü you have to intimately take in the spectrum of Spend three nights on the Pangolin Voyager Botswana’s wildlife. Designed by Naturalist cruising the wildlife-rich Chobe River, where we Journeys’ owner and founder, Peg Abbott, who has watch Elephant, Lion, Sable Antelope, and a host decades of experience visiting Africa, this is an of herons and egrets, including the world’s ultimate experience for seeing Africa’s birds and largest: the Goliath Heron ü iconic large mammals.