'Improving Their Lives.' State Policies and San Resistance in Botswana

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

From Ogoni to Endorois (African System) Through Saramaka (Inter-American System) Does Provide More

INDIGENOUS GROUPS AND THE DEVELOPING JURISPRUDENCE OF THE AFRICAN COMMISSION ON HUMAN AND PEOPLES’ RIGHTS: SOME REFLECTIONS * GAETANO PENTASSUGLIA I. INTRODUCTION The African Charter on Human and Peoples‟ Rights – also known as the African or Banjul Charter (AfrCH) - lies at the core of the African human rights regime. It was adopted in 1981 and entered into force in 1986 following ratification by a majority of member states of the (then) Organisation of African Unity.1 Together with a number of classical individual rights of civil, political and/or socio-economic nature, it enshrines rights of „peoples‟ in Articles 19 through to 24. The AfrCH is monitored by the African Commission on Human and Peoples‟ Rights (ACHPR), which performs both promotional and protective functions. Such functions are principally organised around examining states‟ reports (Article 62), examining communications from individuals, NGOs or states parties on alleged breaches (Articles 47, 55), and interpreting the AfrCH more generally (Article 45(3)). Importantly individuals or NGOs may petition the ACHPR irrespective of whether they are the direct victims of the violation complained of, subject to pre- defined procedural requirements. As the number of African institutions increases,2 the ACHPR still remains central to enhancing human rights protection in Africa.3 * Fernand Braudel Senior Fellow, Department of Law, European University Institute, Italy, 2010; Senior Lecturer in International Law and Director of the International and European Law Unit, University of Liverpool, UK; Visiting Professor, University of Toronto Faculty of Law, Fall 2009. His latest publications include Minority Groups and Judicial Discourse in International Law: A Comparative Perspective (Martinus Nijhoff Publishers, Leiden 2009). -

The Inconvenient Indigenous

1 SIDSEL SAUGESTAD The Inconvenient Indigenous Remote Area Development in Botswana, Donor Assistance, and the First People of the Kalahari The Nordic Africa Institute, 2001 2 The book is printed with support from the Norwegian Research Council. Front cover photo: Lokalane – one of the many small groups not recognised as a community in the official scheme of things Back cover photos from top: Irrigation – symbol of objectives and achievements of the RAD programme Children – always a hope for the future John Hardbattle – charismatic first leader of the First People of the Kalahari Ethno-tourism – old dance in new clothing Indexing terms Applied anthropology Bushmen Development programmes Ethnic relations Government policy Indigenous peoples Nation-building NORAD Botswana Kalahari San Photos: The author Language checking: Elaine Almén © The author and The Nordic Africa Institute 2001 ISBN 91-7106-475-3 Printed in Sweden by Centraltryckeriet Åke Svensson AB, Borås 2001 3 My home is in my heart it migrates with me What shall I say brother what shall I say sister They come and ask where is your home they come with papers and say this belongs to nobody this is government land everything belongs to the State What shall I say sister what shall I say brother […] All of this is my home and I carry it in my heart NILS ASLAK VALKEAPÄÄ Trekways of the Wind 1994 ∫ This conference that I see here is something very big. It can be the beginning of something big. I hope it is not the end of something big. ARON JOHANNES at the opening of the Regional San Conference in Gaborone, October 1993 4 Preface and Acknowledgements The title of this book is not a description of the indigenous people of Botswana, it is a characterisation of a prevailing attitude to this group. -

Botswana Semiology Research Centre Project Seismic Stations In

BOTSWANA SEISMOLOGICAL NETWORK ( BSN) STATIONS 19°0'0"E 20°0'0"E 21°0'0"E 22°0'0"E 23°0'0"E 24°0'0"E 25°0'0"E 26°0'0"E 27°0'0"E 28°0'0"E 29°0'0"E 30°0'0"E 1 S 7 " ° 0 0 ' ' 0 0 ° " 7 S 1 KSANE Kasane ! !Kazungula Kasane Forest ReserveLeshomo 1 S Ngoma Bridge ! 8 " ! ° 0 0 ' # !Mabele * . MasuzweSatau ! ! ' 0 ! ! Litaba 0 ° Liamb!ezi Xamshiko Musukub!ili Ivuvwe " 8 ! ! ! !Seriba Kasane Forest Reserve Extension S 1 !Shishikola Siabisso ! ! Ka!taba Safari Camp ! Kachikau ! ! ! ! ! ! Chobe Forest Reserve ! !! ! Karee ! ! ! ! ! Safari Camp Dibejam!a ! ! !! ! ! ! ! X!!AUD! M Kazuma Forest Reserve ! ShongoshongoDugamchaRwelyeHau!xa Marunga Xhauga Safari Camp ! !SLIND Chobe National Park ! Kudixama Diniva Xumoxu Xanekwa Savute ! Mah!orameno! ! ! ! Safari Camp ! Maikaelelo Foreset Reserve Do!betsha ! ! Dibebe Tjiponga Ncamaser!e Hamandozi ! Quecha ! Duma BTLPN ! #Kwiima XanekobaSepupa Khw!a CHOBE DISTRICT *! !! ! Manga !! Mampi ! ! ! Kangara # ! * Gunitsuga!Njova Wazemi ! ! G!unitsuga ! Wazemi !Seronga! !Kaborothoa ! 1 S Sibuyu Forest Reserve 9 " Njou # ° 0 * ! 0 ' !Nxaunxau Esha 12 ' 0 Zara ! ! 0 ° ! ! ! " 9 ! S 1 ! Mababe Quru!be ! ! Esha 1GMARE Xorotsaa ! Gumare ! ! Thale CheracherahaQNGWA ! ! GcangwaKaruwe Danega ! ! Gqose ! DobeQabi *# ! ! ! ! Bate !Mahito Qubi !Mahopa ! Nokaneng # ! Mochabana Shukumukwa * ! ! Nxabe NGAMILAND DISTRICT Sorob!e ! XurueeHabu Sakapane Nxai National Nark !! ! Sepako Caecae 2 ! ! S 0 " Konde Ncwima ° 0 ! MAUN 0 ' ! ! ' 0 Ntabi Tshokatshaa ! 0 ° ! " 0 PHDHD Maposa Mmanxotai S Kaore ! ! Maitengwe 2 ! Tsau Segoro -

2019 GENERAL ELECTIONS REPORT II Keireng A

REPORT TO THE MINISTER FOR PRESIDENTIAL AFFAIRS, GOVERNANCE AND PUBLIC ADMINISTRATION ON THE 2019 GENERAL ELECTIONS 2019 GENERAL ELECTIONS I REPORT Honourable Justice Abednego B. Tafa Mr. John Carr-Hartley Members of CHAIRMAN DEPUTY CHAIRMAN The Independent Electoral Commission Mrs. Agnes Setlhogile Mrs. Shaboyo Motsamai Dr. Molefe Phirinyane COMMISSIONER COMMISSIONER COMMISSIONER Mrs. Martha J. Sayed Vacant COMMISSIONER COMMISSIONER 2019 GENERAL ELECTIONS REPORT II Keireng A. Zuze Doreen L. Serumula SECRETARY DEPUTY SECRETARY Executive Management of the Secretariat Keolebogile M. Tshitlho Dintle S. Rapoo SENIOR MANAGER MANAGER CORPORATE SERVICES ELECTIONS AFFAIRS & FIELD OPERATIONS Obakeng B. Tlhaodi Uwoga H. Mandiwana CHIEF STATE COUNSEL MANAGER HUMAN RESOURCE & ADMINISTRATION 2019 GENERAL ELECTIONS REPORT III Strategic Foundations ........................................................................................................................... I Members of The Independent Electoral Commission ................................................ II Executive Management of the Secretariat........................................................................... III Letter to The Minister for Presidential Affairs, Governance and Public Administration ............................................................................................................... 1 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS.................................................................................................................. 2 ACRONYMS ............................................................................................................................................... -

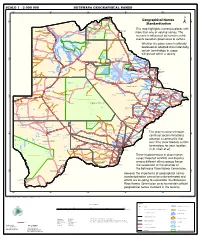

Geographical Names Standardization BOTSWANA GEOGRAPHICAL

SCALE 1 : 2 000 000 BOTSWANA GEOGRAPHICAL NAMES 20°0'0"E 22°0'0"E 24°0'0"E 26°0'0"E 28°0'0"E Kasane e ! ob Ch S Ngoma Bridge S " ! " 0 0 ' ' 0 0 ° Geographical Names ° ! 8 !( 8 1 ! 1 Parakarungu/ Kavimba ti Mbalakalungu ! ± n !( a Kakulwane Pan y K n Ga-Sekao/Kachikaubwe/Kachikabwe Standardization w e a L i/ n d d n o a y ba ! in m Shakawe Ngarange L ! zu ! !(Ghoha/Gcoha Gate we !(! Ng Samochema/Samochima Mpandamatenga/ This map highlights numerous places with Savute/Savuti Chobe National Park !(! Pandamatenga O Gudigwa te ! ! k Savu !( !( a ! v Nxamasere/Ncamasere a n a CHOBE DISTRICT more than one or varying names. The g Zweizwe Pan o an uiq !(! ag ! Sepupa/Sepopa Seronga M ! Savute Marsh Tsodilo !(! Gonutsuga/Gonitsuga scenario is influenced by human-centric Xau dum Nxauxau/Nxaunxau !(! ! Etsha 13 Jao! events based on governance or culture. achira Moan i e a h hw a k K g o n B Cakanaca/Xakanaka Mababe Ta ! u o N r o Moremi Wildlife Reserve Whether the place name is officially X a u ! G Gumare o d o l u OKAVANGO DELTA m m o e ! ti g Sankuyo o bestowed or adopted circumstantially, Qangwa g ! o !(! M Xaxaba/Cacaba B certain terminology in usage Nokaneng ! o r o Nxai National ! e Park n Shorobe a e k n will prevail within a society a Xaxa/Caecae/Xaixai m l e ! C u a n !( a d m a e a a b S c b K h i S " a " e a u T z 0 d ih n D 0 ' u ' m w NGAMILAND DISTRICT y ! Nxai Pan 0 m Tsokotshaa/Tsokatshaa 0 Gcwihabadu C T e Maun ° r ° h e ! 0 0 Ghwihaba/ ! a !( o 2 !( i ata Mmanxotae/Manxotae 2 g Botet N ! Gcwihaba e !( ! Nxharaga/Nxaraga !(! Maitengwe -

LOST LANDS? (Land) Rights of the San in Botswana and the Legal Concept of Indigeneity in Africa

Manuela Zips-Mairitsch LOST LANDS? (Land) Rights of the San in Botswana and the Legal Concept of Indigeneity in Africa LIT Contents Acknowledgements 9 Preface by Rene 13 Introduction 21 Part 1: Indigenous Peoples in International Law I. Historical Overview 29 II. "Indigenous Peoples": Term, Concepts, and Definitions 34 Differentiation from Term "Minority" 40 III. Special Indigenous Rights or Special Circumstances? Indigenous Protection Standards, Rights of Freedom, and 42 1. Sources of Law 42 1.1 Binding Norms 43 1.1.1 Convention 169 43 1.1.2 UN Convention on Biological Diversity 45 1.2 "Soft law" Instruments 46 1.2.1 Agenda 21, Chapter 26 (1992) 47 1.2.2 UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples 47 1.2.3 Declarations and Policies of various International Bodies 52 1.3 Indigenous Rights as Part of Customary International Law 56 2. "Sources of Life": Lands and Natural Resources 57 2.1 Material Standards of Protection 57 2.1.1 Cause of Action 58 2.1.2 The Relationship between Indigenous Peoples and their Territories 59 2.1.3 Collective Land Rights 61 2.1.4 Scope of Indigenous Territories 63 2.1.5 Restriction of Alienation and Disposal 64 2.2 Universal Human Rights Treaties 64 2.2.1 Right of Ownership 65 2.2.2 Right to Culture 66 2.2.3 Right to Private and Family Life 66 2.3 Jurisdiction of International Monitoring Bodies 67 2.3.1 Human Rights Committee 67 2.3.2 Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination 68 3. -

DEVELOPMENT DESTROYS Thekill HEALTH of TRIBAL PEOPLES

LAND AND LIFE Progress can HOW IMPOSED DEVELOPMENT DESTROYS THEkill HEALTH OF TRIBAL PEOPLES a Survival International publication ‘OUTSIDERS WHO COME HERE ALWAYS CLAIM THEY ARE BRINGING PROGRESS. BUT ALL THEY BRING ARE EMPTY PROMISES. WHAT WE’RE REALLY STRUGGLING FOR IS OUR LAND. ABOVE ALL ELSE THIS IS WHAT WE NEED.’ ARAU, PENAN MAN, SARAWAK, MALAYSIA, 2007 contents * 1 INTRODUCTION: LAND AND LIFE 1 2 LONG-TERM IMPACTS OF SETTLEMENT ON HEALTH 10 3 IDENTITY, FREEDOM AND MENTAL HEALTH 22 4 MATERNAL AND SEXUAL HEALTH 28 5 HEALTHCARE 33 6 CONCLUSION: HEALTH AND FUTURE 42 Introduction: Land and Life Across the world, from the poorest to ‘We are not poor or primitive. * the richest countries, indigenous peoples We Yanomami are very rich. Rich today experience chronic ill health. They in our culture, our language and endure the worst of the diseases that our land. We don’t need money accompany poverty and, simultaneously, or possessions. What we need many suffer from ‘diseases of affluence’ is respect: respect for our culture – such as cancers and obesity – despite and respect for our land rights.’ often receiving few of the benefits of Davi Kopenawa Yanomami, Brazil 1995. ‘development’. Diabetes alone threatens the very survival of many indigenous Tribal peoples who have suffered communities in rich countries.3 Indigenous colonisation, forced settlement, peoples also experience serious mental assimilation policies and other ‘You napëpë [whites] talk about health problems and have high levels forms of marginalisation and removal what you call “development” and of substance abuse and suicide. The from ancestral lands almost always tell us to become the same as you. -

Water Access and Dispossession in Botswana's Central Kalahari Game

Fall 08 2013 216 Rethinking the human right to water: Water access and dispossession in Botswana’s Central Kalahari Game Reserve Cynthia Morinville and Lucy Rodina Institute For Resources, Environment and Sustainability, The University oF British Columbia2202 Main Mall, Vancouver, BC V6T 1Z4, CanadaCorresponding author: [email protected] Final Version: C. Morinville and L. Rodina. 2013. Rethinking the human right to water: Water access and dispossession in Botswana’s Central Kalahari Game Reserve. GeoForum 49: 150- 159.http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.geoForum.2013.06.012Citation oF this work should use the Final version as noted above. Rethinking the Human Right to Water: Water Access and Dispossession in Botswana’s Central Kalahari Game Reserve Abstract This paper engages debates regarding the human right to water through an exploration the recent legal battle between San and Bakgalagadi and the government of Botswana regarding access to water in the Central Kalahari Game Reserve. The paper reviews the legal events that led to the realization of the human right to water through a decision of the Court of Appeal of Botswana in 2011 and the discursive context in which these events took place. We offer a contextual evaluation of the processes that allowed the actual realization of the human right to water for the residents of the Central Kalahari Game Reserve, revisiting and extending dominant lines of inquiry related to the human right to water in policy and academic debates. Adding to these discussions, we suggest the use of ‘dispossession’ as an analytical lens is a useful starting point for a conceptual reframing of the human right to water. -

University of Cape Town (UCT) in Terms of the Non-Exclusive License Granted to UCT by the Author

The copyright of this thesis vests in the author. No quotation from it or information derived from it is to be published without full acknowledgement of the source. The thesis is to be used for private study or non- commercial research purposes only. Published by the University of Cape Town (UCT) in terms of the non-exclusive license granted to UCT by the author. University of Cape Town Government Policy Direction in Botswana, Namibia, and South Africa to their San Communities: Local Implications of the International Indigenous Peoples'Movement Bonney Elizabeth HARTLEY HRTBON001 A minor dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the award of the degree of Master of Arts in Political Studies University of Cape Town Faculty of Humanities University of Cape Town 2007 COl'ernment Policy Direction in Botswana, Bonney Hartley Namihia, and South Africa to their San Communities: Local Implications of the International Indigenous Peoples' Movement Compulsory declaration This work has not been previously submitted in whole, or in part, for the award of any degree. It is my own work. Each significant contribution to, and quotation in, this dissertation from the work, or works, of other people has been attributed and has been cited and referenced. signatureqJ .f{w\ttwy removed Bonney Hartley 16 February 2007 University of Cape Town Government Polic .... [)ireetion in Botswana, Bonney Hartley Namibia, and South Africa to their San Communities: Local Implications of the International Indigenous Peoples' Movement Abstract As the movement of indigenous peoples' rights, largely based in the experience of Indians of the Americas, has expanded to include the particular African context of what constitutes an "indigenous peoples," new discussions have emerged amongst governments in the southern African region over their San communities. -

Indigeneity and Development in Botswana the Case of the San in the Central Kalahari Game Reserve Jonathan Woof

1 Indigeneity and Development in Botswana The Case of the San in the Central Kalahari Game Reserve Jonathan Woof 1 Abstract: This paper discusses how San involved with the Central Kalahari Game Reserve (CKGR) in Botswana express and interpret their sense of indigeneity amidst the systemic marginalization and discrimination that they have experienced. By looking in depth at the case in the CKGR, the nature of prominent San CSOs and impact of the ‘Global North,’ this paper finds that San affirm their sense of indigeneity by critiquing the post-colonial development discourse, attempting to restore their land rights in the CKGR and by implementing ‘life-projects’ which affirm their ontologies and traditions. The findings of the paper suggest that the concept of indigeneity is diverse and complex and may not be as liberating as its proponents hope. 2 Table of Contents Introduction, Methodology and Theoretical Framework .................................................... 1-11 Chapter 1: The Concept of Indigeneity and its Manifestations in Africa and in Botswana... 12-22 Chapter 2: Indigeneity Within the San Community ............................................................... 23-36 Chapter 3: Survival International’s Perception of Indigeneity Compared to the San Community .................................................................................................................................................. 37-41 Chapter 4: Current State of Affairs for the San in the CKGR .............................................. 42-46 Conclusion -

Indigenous Peoples' Rights in Southern Africa

INDIGENOUS PEOPLES’ RIGHTS IN SOUTHERN AFRICA: AN INTRODUCTION Robert K. Hitchcock Diana Vinding ndigenous peoples in Africa and their rights have been the focus of I much deliberation and debate in recent years.1 These discussions have taken place in academic institutions and journals in Africa, Eu- rope and North America, as well as within the European Union, the World Bank and the United Nations. A major area of dissent has been whether the concept of “indige- nousness”, and hence of specific “indigenous” rights, could be used in an African context. Most African governments have until now main- tained that all their citizens are indigenous or, alternatively, argued that there is no such thing as an indigenous group in their country. Some researchers and social scientists have stressed that the problems faced by certain ethnic minorities have more to do with poverty than cultur- al differences and the problems they face should therefore be alleviated by welfare and development measures (see Saugestad, this volume). There is no single, agreed-upon definition of the term “indigenous peoples” but, as Saugestad mentions in her Overview (this volume), the four most often invoked elements are: (1) a priority in time; (2) the voluntary perpetuation of cultural distinctiveness; (3) an experience of subjugation, marginalisation and dispossession; (4) and self-identifica- tion. Often, the term indigenous is used to refer to those individuals and groups who are descendants of the original populations (that is, the “first nations”) residing in a country. In the case of Africa this rais- es particular problems. Africa is the continent with the longest history of human occupation, and it contains the greatest range of human ge- netic and cultural diversity. -

Digging in During the Dry Season

JGW-6 SOUTHERN AFRICA James Workman is a Donors’ Fellow of the Institute studying the use, misuse, accretion and depletion of ICWA fresh-water supplies in southern Africa. Line in the Sand: LETTERS Digging in During the Dry Season Since 1925 the Institute of By James G. Workman Current World Affairs (the Crane- Rogers Foundation) has provided METSIMENONG, BOTSWANA, Wednesday 16 July–Just before noon we hear the government vehicles rumbling toward us across the Kalahari. A breeze car- long-term fellowships to enable ries the engines’ noise through the winter air of this semi-desert and interrupts outstanding young professionals the small gathering of Bushmen meeting here to exchange news. to live outside the United States and write about international For the past half hour two Bushmen leaders from outside the Central Kalahari areas and issues. An exempt Game Reserve (CKGR) — Roy Sesana and Mathambo NgaKaeaja — have been operating foundation endowed by updating these last intransigent peoples on the slow progress of a court battle the late Charles R. Crane, the being waged to make the government let them remain legally in their ancestral Institute is also supported by homeland. In turn, the three-dozen men, women and children tell what it’s like to contributions from like-minded stay put for months on end while officially cut off from water, food, communica- individuals and foundations. tions or medicine. As the powerful Land Cruisers approach, voices momentarily fall silent. Mathambo breaks off in mid-sentence and turns. “You guys better hide your TRUSTEES cameras,” he says, and we rise to move.