Recovering and Reconstructing Leftist Shakespeares by Jeffrey Butcher

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Online Finding

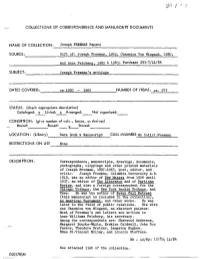

COLLECTIONS OF CORRESPONDENCE AND MANUSCRIPT DOCUMENTS NAME OF COLLECTION: Joseph FREEMAN Papers SOURCE: Gift of; Joseph Freeman, 1952; Charmion Von Wiegand, 1980; and Anne Feinberg, 1982 & 1983; Purchase 293-7/H/8U SUBJECT: Joseph Freeman's "writings DATES COVERED: ca.1920 - 1965 NUMBER OF ITEMS: ca. 675 STATUS: (check appropriate description) Cataloged: x Listed: x Arranged: Not organized: CONDITION: (give number of vols., boxes, or shelves) Bound: Boxed: o Stored: LOCATION: (Library) Rare Book & Manuscript CALL-NUMBER Ms Coll/J.Freeman RESTRICTIONS ON USE None DESCRIPTION: Correspondence, manuscripts, drawings, documents, photographs, clippings and other printed materials of Joseph Freeman, 1897-19&55 poet, editor, and critic. Joseph Freeman, Columbia University A.B. 1919» was an editor of New Masses from 1926 until 1937 j an editor of The Liberator and of Partisan Review, and also a foreign correspondent for the Chicago Tribune, the New York Herald Tribune, and Tass. He was the author of Never Call Retreat (this manuscript is included in the collection), An American Testament, and other works. He was later in the field of public relations. His wife was Charmion von Wiegand, an abstract painter. Most of Freeman's own letters are written to Anne Williams Feinberg, his secretary. Among the correspondents are: Sherwood Anderson, Margaret Bourke-White, Erskine Caldwell, John Dos Passos, Theodore Dreiser, Langston Hughes, Edna St.Vincent Millay, and Lincoln Steffens. HR - 12/82; 12/83; 11/8U See attached list of the collection. D3(178)M Joseph. Freeman Papers Box 1 Correspondence 8B misc. Cataloged correspondence & drawings: Anderson, Sherwood Harcourt, Alfred Bodenheim, Maxwell Herbst, Josephine Frey Bourke-White, Margaret Hughes, Langston Brown, Gladys Humphries, Rolfe Caldwell, Erskine Kent, Rockwell Dahlberg, Edward Komroff, Manuel Dehn, Adolph ^Millaf, Edna St. -

Text Fly Within

TEXT FLY WITHIN THE BOOK ONLY 00 u<OU_1 68287 co ^ co> OSMANIA UNIVERSITY LIBRARY t*o-* 7 Alt i^- Gall No. / Accession No. Author 0ttSkts "J- . Title /v- 4he f'/* Kt^fa/iie ^rU^ r -*JU" ' This book should be returned on or before the date last marked below. THE REINTERPRETJLTION OF VICTORIAN LITERATURE THE REINTERPRETATION OF VICTORIAN LITERATURE EDITED BY JOSEPH E. BAKER FOR THE VICTORIAN LITERATURE CROUP OF THE MODERN LANGUAGE ASSOCIATION OF AMERICA PRINCETON, NEW JERSEY PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS 1950 COPYRIGHT, 1950, BY PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS LONDON: GEOFFREY CUMBERLEGE, OXFORD UNIVERSITY PRESS PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA BY PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS AT PRINCETON, NEW JERSEY PREFACE THE Victorian Literature Group of the Modern Language Association of America, at the 1939 meeting in New Or- leans, agreed to put out this volume to further the reinter- pretation of a literature of great significance for us today. The writers of Victorian England first tried* to salvage humane culture for a new world of science, democracy, and industrialism. We owe to them and to Pre-Victorians like the prose Coleridge a revival of Christian thought, a new Classical renaissance (this time Greek rather than Latin), an unprecedented mastery of the facts about nature and man and, indeed, the very conception of "culture" that we take for granted in our education and in our social plan- ning. In that age, a consciousness that human life is subject to constant development, a sense of historicity, first spread throughout the general public, and literature for -The first time showed that intimate integration with its sociafback- ground which marks our modern culture. -

Lorine Niedecker's Personal Library of Books: A

LORINE NIEDECKER’S PERSONAL LIBRARY OF BOOKS: A BIBLIOGRAPHY Margot Peters Adams, Brooks. The Law of Civilization and Decay. New York: Vintage Books, 1955. Adéma, Marcel. Apollinaire, trans, Denise Folliot. London: Heineman, 1954. Aldington, Hilda Doolittle (H.D.). Heliodora and Other Poems. Boston: Houghton, Mifflin, 1924. Aldington, Richard, ed. The Religion of Beauty: Selections from the Aesthetes. London: Heineman, 1950. Alighieri, Dante. The Divine Comedy. New York: Random House, 1950. Allen, Donald M., ed. The New American Poetry: 1945-1960. New York: Grove Press, 1960. Allen, Glover Morrill. Birds and Their Attributes. New York: Dover, 1962. Alvarez, A. The School of Donne. New York: Mentor, 1967. Anderson, Charles R. Emily Dickinson’s Poetry: Stairway of Surprise. New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston, 1960. Anderson, Sherwood. Six Mid-American Chants. Photos by Art Sinsabaugh. Highlands, N.C.: Jargon Press, 1964. Arnett, Willard E. Santayana and the Sense of Beauty. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 1957. Arnold, Matthew. Passages from the Prose Writings of Matthew Arnold, ed. William E. Buckler, New York: New York University Press, 1963. Saint Augustine. The Confessions. New York: Pocket Books, n.d. Aurelius, Marcus (Marcus Aelius Aurelius Antoninus). Meditations. London: Dent, 1948. Bacon, Francis. Essays and the New Atlantis, ed. Gordon S. Haight. New York: Van Nostrand, 1942. Basho. The Narrow Road to the Deep North and Other Travel Sketches, trans. Nobuyuki Yuasa. Baltimore: Penguin, 1966. 1 Baudelaire, Charles. Flowers of Evil. New York: New Directions, 1958. Beard, Charles A. & Mary R. Beard. The Rise of American Civilization. New York: Macmillan, 1939. Bell, Margaret. Margaret Fuller: A Biography. -

Lorne Bair :: Catalog 21

LORNE BAIR :: CATALOG 21 1 Lorne Bair Rare Books, ABAA PART 1: AFRICAN-AMERICAN HISTORY & LITERATURE 2621 Daniel Terrace Winchester, Virginia USA 22601 (540) 665-0855 Email: [email protected] Website: www.lornebair.com TERMS All items are offered subject to prior sale. Unless prior arrangements have been made, payment is expected with order and may be made by check, money order, credit card (Visa, MasterCard, Discover, American Express), or direct transfer of funds (wire transfer or Paypal). Institutions may be billed. Returns will be accepted for any reason within ten days of receipt. ALL ITEMS are guaranteed to be as described. Any restorations, sophistications, or alterations have been noted. Autograph and manuscript material is guaranteed without conditions or restrictions, and may be returned at any time if shown not to be authentic. DOMESTIC SHIPPING is by USPS Priority Mail at the rate of $9.50 for the first item and $3 for each additional item. Overseas shipping will vary depending upon destination and weight; quotations can be supplied. Alternative carriers may be arranged. WE ARE MEMBERS of the ABAA (Antiquarian Bookseller’s Association of America) and ILAB (International League of Antiquarian Book- sellers) and adhere to those organizations’ standards of professionalism and ethics. PART ONE African American History & Literature ITEMS 1-54 PART TWO Radical, Social, & Proletarian Literature ITEMS 55-92 PART THREE Graphics, Posters & Original Art ITEMS 93-150 PART FOUR Social Movements & Radical History ITEMS 151-194 2 PART 1: AFRICAN-AMERICAN HISTORY & LITERATURE 1. CUNARD, Nancy (ed.) Negro Anthology Made by Nancy Cunard 1931-1933. London: Nancy Cunard at Wishart & Co., 1934. -

Vol. X. No.1 CONTENTS No Rights for Lynchers...• . . • 6

VoL. X. No.1 CONTENTS JANUARY 2, 19:34 No Rights for Lynchers. • . • 6 The New Republic vs. the Farmers •••••• 22 Roosevelt Tries Silver. 6 Books . .. .. • . • . • 24 Christmas Sell·Out ••••.......••..•.•••• , 7 An Open Letter by Granville Hicks ; Fascism in America, ••..• by John Strachey 8 Reviews by Bill Dunne, Stanley Burn shaw, Scott Nearing, Jack Conroy. The Reichstag Trial •• by Leonard L Mins 12 Doves in the Bull Ring .. by John Dos Passos 13 ·John Reed Club Art Exhibition ......... ' by Louis Lozowick 27 Is Pacifism Counter-Revolutionary ••••••• by J, B. Matthews 14 The Theatre •.•••... by William Gardener 28 The Big Hold~Up •••••••••••••••••••.•• 15 The Screen ••••••••••••• by Nathan Adler 28 Who Owns Congress •• by Marguerite Young 16 Music .................. by Ashley Pettis 29 Tom Mooney Walks at Midnight ••.••.•• Cover •••••• , ••••••• by William Gropper by Michael Gold 19 Other Drawinp by Art Young, Adolph The Farmen Form a United Front •••••• Dehn, Louis Ferstadt, Phil Bard, Mardi by Josephine Herbst 20 Gasner, Jacob Burck, Simeon Braguin. ......1'11 VOL, X, No.2 CONTENTS 1934 The Second Five~ Year Plan ........... , • 8 Books •••.•.••.••.•••••••••••••••••.••• 25 Writing and War ........ Henri Barbusse 10 A Letter to the Author of a First Book, by Michael Gold; Of the World Poisons for People ••••••••• Arthur Kallet 12 Revolution, by Granville Hicks; The Union Buttons in Philly ••••• Daniel Allen 14 Will Durant of Criticism, by Philip Rahv; Upton Sinclair's EPIC Dream, "Zafra Libre I" ••.••••..•• Harry Gannes 15 by William P. Mangold. A New Deal in Trusts .••• David Ramsey 17 End and Beginning .• Maxwell Bodenheim 27 Music • , • , •••••••••••••••. Ashley Pettis 28 The House on 16th Street ............. -

John Ahouse-Upton Sinclair Collection, 1895-2014

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/c8cn764d No online items INVENTORY OF THE JOHN AHOUSE-UPTON SINCLAIR COLLECTION, 1895-2014, Finding aid prepared by Greg Williams California State University, Dominguez Hills Archives & Special Collections University Library, Room 5039 1000 E. Victoria Street Carson, California 90747 Phone: (310) 243-3895 URL: http://www.csudh.edu/archives/csudh/index.html ©2014 INVENTORY OF THE JOHN "Consult repository." 1 AHOUSE-UPTON SINCLAIR COLLECTION, 1895-2014, Descriptive Summary Title: John Ahouse-Upton Sinclair Collection Dates: 1895-2014 Collection Number: "Consult repository." Collector: Ahouse, John B. Extent: 12 linear feet, 400 books Repository: California State University, Dominguez Hills Archives and Special Collections Archives & Special Collection University Library, Room 5039 1000 E. Victoria Street Carson, California 90747 Phone: (310) 243-3013 URL: http://www.csudh.edu/archives/csudh/index.html Abstract: This collection consists of 400 books, 12 linear feet of archival items and resource material about Upton Sinclair collected by bibliographer John Ahouse, author of Upton Sinclair, A Descriptive Annotated Bibliography . Included are Upton Sinclair books, pamphlets, newspaper articles, publications, circular letters, manuscripts, and a few personal letters. Also included are a wide variety of subject files, scholarly or popular articles about Sinclair, videos, recordings, and manuscripts for Sinclair biographies. Included are Upton Sinclair’s A Monthly Magazine, EPIC Newspapers and the Upton Sinclair Quarterly Newsletters. Language: Collection material is primarily in English Access There are no access restrictions on this collection. Publication Rights All requests for permission to publish or quote from manuscripts must be submitted in writing to the Director of Archives and Special Collections. -

Diego Rivera and the Left: the Destruction and Recreation of the Rockefeller Center Mural

Diego Rivera and the Left: The Destruction and Recreation of the Rockefeller Center Mural Dora Ape1 Diego Rivera, widely known for his murals at the Detroit Institute ofArts and the San Francisco Stock Exchange Luncheon Club, became famous nationally and internationally when his mural for the Radio City ofAmerica (RCA) Building at Rockefeller Center in New York City was halted on 9 May 1933, and subsequently destroyed on 10 February 1934. Commissioned at the height of the Depression and on the eve of Hitler's rise to power, Rivera's mural may be read as a response to the world's political and social crises, posing the alternatives for humanity as socialist harmony, represented by Lenin and scenes of celebration from the Soviet state, or capitalist barbarism, depicted through scenes of unemployment, war and "bourgeois decadence" in the form of drinking and gambling, though each side contained ambiguous elements. At the center stood contemporary man, the controller of nature and industrial power, whose choice lay between these two fates. The portrait of Lenin became the locus of the controversy at a moment when Rivera was disaffected with the policies of Stalin, and the Communist Party (CP) opposition was divided between Leon Trotsky and the international Left Opposition on one side, and the American Right Opposition led by Jay Lovestone on the other. In his mural, Rivera presented Lenin as the only historical figure who could clearly symbolize revolutionary political leadership. When he refused to remove the portrait of Lenin and substitute an anonymous face, as Nelson Rockefeller insisted, the painter was summarily dismissed, paid off, and the unfinished mural temporarily covered up, sparking a nationwide furor in both the left and capitalist press. -

American Communists View Mexican Muralism: Critical and Artistic Responses1

AMERICAN COMMUNISTS VIEW MEXICAN MURALISM: CRITICAL AND ARTISTIC RESPONSES1 Andrew Hemingway A basic presupposition of this essay is 1My thanks to Jay Oles for his helpful cri- that the influence of Mexican muralism ticisms of an earlier version of this essay. on some American artists of the inter- While the influence of Commu- war period was fundamentally related nism among American writers of the to the attraction many of these same so-called "Red Decade" of the 1930s artists felt towards Communism. I do is well-known and has been analysed not intend to imply some simple nec- in a succession of major studies, its essary correlation here, but, given the impact on workers in the visual arts revolutionary connotations of the best- is less well understood and still under- known murals and the well-publicized estimated.3 This is partly because the Marxist views of two of Los Tres Grandes, it was likely that the appeal of this new 2I do not, of course, mean to discount artistic model would be most profound the influence of Mexican muralism on non-lef- among leftists and aspirant revolutionar- tists such as George Biddle and James Michael ies.2 To map the full impact of Mexican Newell. For Biddle on the Mexican example, see his 'Mural Painting in America', Magazine of Art, muralism among such artists would be vol. 27, no. 7, July 1934, pp.366-8; An American a major task, and one I can not under- Artist's Story, Boston, Little, Brown and Company, take in a brief essay such as this. -

European Academic Research

EUROPEAN ACADEMIC RESEARCH Vol. IV, Issue 4/ July 2016 Impact Factor: 3.4546 (UIF) ISSN 2286-4822 DRJI Value: 5.9 (B+) www.euacademic.org The Origin and Development of the Proletarian Novel JAVED AKHTER Department of English Literature University of Baluchistan, Quetta, Pakistan Abstract: This research paper tends to trace the origin and development of the mature proletarian revolutionary novel. The mature revolutionary proletarian novels will be discussed and highlighted in this study in terms of Marxist hermeneutics This new literary kind did not come into being prior to the imperialist era because the socio- economic requirements for this literary genre were non-existent and the proletarian movement did not enter into its decisive historical stage of development. This new genre of the novel appeared simultaneously in the works of Robert Tressell, Martin Anderson Nexo, Upton Sinclair and Maxim Gorky in the beginning of the twentieth century. In this era of imperialism, the proletarian novel came into existence, when the socio-historical ethos brought the proletarian movement into being as well as helped to organise and develop it on international level. At the end of this analytical and comparative study of them, the noticeable point is that the proletarian novels of that period share astonishing similarities with one another. Applying Marxist literary hermeneutics to the art of novel writing of the famous proletarian novelists, this research paper will try to introduce new portrait of the personages of the novels of these proletarian -

New- MASSES •• •• MAY, %9Z6

NEw- MASSES •• MAY, %9Z6 IS THIS IT? IN THIS ISSUE Is this the magazine our prospectuses THE WRITERS talked about? We are not so sure. This, BABETTE DEUTSCH, winner however, is undoubtedly the editorial which, of this year's "Nation" Poetry Prize, in all our prospectuses, we promised faith has published two volumes of poetry. fully not to write. She has recently visited Soviet Russia. As to the magazine, we regard it with ROBERT DlJNN is the author of "Ameri· almost complete detachment and a good deal can Foreign Investments" and co-author with of critical interest, because we didn"t make Sidney Howard of it ourselves. "The Labor Spy." ROBINSON JEFFERS' "Roan Stallion, We merely "discovered"" it. Tamar and Other Poems," published last We were confident that somewhere in year, established him as one of the impor• America a NEW MASSES existed, if only as tant contemporary American poets, He live. a frustrated desire. in Carmel, Calif. To materialize it, all that was needed was WILLIAM CARLOS WILLIAMS is well to make a certain number of prosaic editorial known as physician, modernist, poet and motions. story-writer, and is the author of "In the American Crain... We made the motions, material poured in, and we sent our first issue to the printer. NATHAN ASCH is the author of a collec tion of vivid short stories published last Next month we shall make, experimentally, year under the title, "The Office." He slightly different lives motions, and a somewhat in Paris. different NEW MASSES will blossom pro fanely on the news-stands in the midst of NORMAN STUDER Ia one of the editors our respectable contemporaries, the whiz of the "New Student." bangs,. -

Эптон Синклер Против Литературного Рынка: Рецепция Трактатов «Медная Марка», «Искусство Маммоны» И «Деньги Пишут!» В Американской Прессе 1920-Х Годов

ВЕСТНИК ПЕРМСКОГО УНИВЕРСИТЕТА. РОССИЙСКАЯ И ЗАРУБЕЖНАЯ ФИЛОЛОГИЯ 2019. Том 11. Выпуск 2 УДК 821(7/8).09 doi 10.17072/2073-6681-2019-2-94-101 ЭПТОН СИНКЛЕР ПРОТИВ ЛИТЕРАТУРНОГО РЫНКА: РЕЦЕПЦИЯ ТРАКТАТОВ «МЕДНАЯ МАРКА», «ИСКУССТВО МАММОНЫ» И «ДЕНЬГИ ПИШУТ!» В АМЕРИКАНСКОЙ ПРЕССЕ 1920-х ГОДОВ Екатерина Витальевна Кешарпу аспирант кафедры истории зарубежной литературы Московский государственный университет им. М. В. Ломоносова 119991, Россия, г. Москва, Ленинские горы, 1. [email protected] SPIN-код: 9683-3837 ORCID: http://orcid.org/0000-0001-7873-0896 ResearcherID: A-3345-2019 Статья поступила в редакцию 10.01.2019 Просьба ссылаться на эту статью в русскоязычных источниках следующим образом: Кешарпу Е. В. Эптон Синклер против литературного рынка: рецепция трактатов «Медная марка», «Искусство Маммоны» и «Деньги пишут!» в американской прессе 1920-х годов // Вестник Пермского университета. Рос- сийская и зарубежная филология. 2019. Т. 11, вып. 2. С. 94–101. doi 10.17072/2073-6681-2019-2-94-101 Please cite this article in English as: Kesharpu E. V. Epton Sinkler protiv literaturnogo rynka: retseptsiya traktatov «Mednaya marka», «Iskusstvo Mam- mony» i «Den’gi pishut!» v amerikanskoy presse 1920-kh gg. [Upton Sinclair against the Literary Market: the Recep- tion of the Treatises ‘The Brass Check’, ‘Mammonart’ and ‘Money Writes!’ in the American Press, 1920s]. Vestnik Permskogo universiteta. Rossiyskaya i zarubezhnaya filologiya [Perm University Herald. Russian and Foreign Philolo- gy], 2019, vol. 11, issue 2, pp. 94–101. doi 10.17072/2073-6681-2019-2-94-101 (In Russ.) Исследование посвящено анализу критических откликов на три трактата Эптона Синклера – «Медная марка» (The Brass Check, 1920), «Искусство Маммоны» (Mammonart, 1925) и «Деньги пи- шут!» (Money Writes!, 1927)) в американской прессе 1920-х гг. -

Dictatorsh I P and Democracy Soviet Union

\\. \ 001135 DICTATORSH IP AND DEMOCRACY IN THE SOVIET UNION FLORIDA ATLANTIC UNIVERSITY LIBRARY SOCIALIST· LABOR CO~lECTlON by Anna Louise Strong No. 40 INTERNATIONAL PAMPHLETS 779 Broadway New York 5 cents PUBLISHERS' NOTE THIS pamphlet, prepared under the direction of Labor Re search Association, is one of a series published by Interna tional Pamphlets, 799 Broadway, New York, from whom additional copies may be obtained at five cents each. Special rates on quantity orders. IN THIS SERIES OF PAMPHLETS I. MODERN FARMING-SOVIET STYLE, by Anna Louise Strong IO¢ 2. WAR IN THE FAR EAST, by Henry Hall. IO¢ 3. CHEMICAL WARFARE, by Donald Cameron. "" IO¢ 4. WORK OR WAGES, by Grace Burnham. .. .. IO¢ 5. THE STRUGGLE OF THE MARINE WORKERS, by N. Sparks IO¢ 6. SPEEDING UP THE WORKERS, by James Barnett . IO¢ 7. YANKEE COLONIES, by Harry Gannes 101 8. THE FRAME-UP SYSTEM, by Vern Smith ... IO¢ 9. STEVE KATOVIS, by Joseph North and A. B. Magil . IO¢ 10. THE HERITAGE OF GENE DEllS, by Alexander Trachtenberg 101 II. SOCIAL INSURANCE, by Grace Burnham. ...... IO¢ 12. THE PARIS COMMUNE--A STORY IN PICTURES, by Wm. Siegel IO¢ 13. YOUTH IN INDUSTRY, by Grace Hutchins .. IO¢ 14. THE HISTORY OF MAY DAY, by Alexander Trachtenberg IO¢ 15. THE CHURCH AND THE WORKERS, by Bennett Stevens IO¢ 16. PROFITS AND WAGES, by Anna Rochester. IO¢ 17. SPYING ON WORKERS, by Robert W. Dunn. IO¢ 18. THE AMERICAN NEGRO, by James S. Allen . IO¢ 19. WAR IN CHINA, by Ray Stewart. .... IO¢ 20. SOVIET CHiNA, by M. James and R.