American Communists View Mexican Muralism: Critical and Artistic Responses1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Online Finding

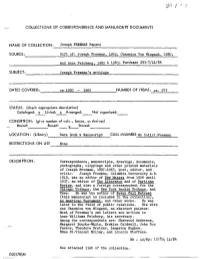

COLLECTIONS OF CORRESPONDENCE AND MANUSCRIPT DOCUMENTS NAME OF COLLECTION: Joseph FREEMAN Papers SOURCE: Gift of; Joseph Freeman, 1952; Charmion Von Wiegand, 1980; and Anne Feinberg, 1982 & 1983; Purchase 293-7/H/8U SUBJECT: Joseph Freeman's "writings DATES COVERED: ca.1920 - 1965 NUMBER OF ITEMS: ca. 675 STATUS: (check appropriate description) Cataloged: x Listed: x Arranged: Not organized: CONDITION: (give number of vols., boxes, or shelves) Bound: Boxed: o Stored: LOCATION: (Library) Rare Book & Manuscript CALL-NUMBER Ms Coll/J.Freeman RESTRICTIONS ON USE None DESCRIPTION: Correspondence, manuscripts, drawings, documents, photographs, clippings and other printed materials of Joseph Freeman, 1897-19&55 poet, editor, and critic. Joseph Freeman, Columbia University A.B. 1919» was an editor of New Masses from 1926 until 1937 j an editor of The Liberator and of Partisan Review, and also a foreign correspondent for the Chicago Tribune, the New York Herald Tribune, and Tass. He was the author of Never Call Retreat (this manuscript is included in the collection), An American Testament, and other works. He was later in the field of public relations. His wife was Charmion von Wiegand, an abstract painter. Most of Freeman's own letters are written to Anne Williams Feinberg, his secretary. Among the correspondents are: Sherwood Anderson, Margaret Bourke-White, Erskine Caldwell, John Dos Passos, Theodore Dreiser, Langston Hughes, Edna St.Vincent Millay, and Lincoln Steffens. HR - 12/82; 12/83; 11/8U See attached list of the collection. D3(178)M Joseph. Freeman Papers Box 1 Correspondence 8B misc. Cataloged correspondence & drawings: Anderson, Sherwood Harcourt, Alfred Bodenheim, Maxwell Herbst, Josephine Frey Bourke-White, Margaret Hughes, Langston Brown, Gladys Humphries, Rolfe Caldwell, Erskine Kent, Rockwell Dahlberg, Edward Komroff, Manuel Dehn, Adolph ^Millaf, Edna St. -

The Power of Political Cartoons in Teaching History. Occasional Paper. INSTITUTION National Council for History Education, Inc., Westlake, OH

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 425 108 SO 029 595 AUTHOR Heitzmann, William Ray TITLE The Power of Political Cartoons in Teaching History. Occasional Paper. INSTITUTION National Council for History Education, Inc., Westlake, OH. PUB DATE 1998-09-00 NOTE 10p. AVAILABLE FROM National Council for History Education, 26915 Westwood Road, Suite B-2, Westlake, OH 44145-4657; Tel: 440-835-1776. PUB TYPE Reports Descriptive (141) EDRS PRICE MF01/PC01 Plus Postage. DESCRIPTORS *Cartoons; Elementary Secondary Education; Figurative Language; *History Instruction; *Humor; Illustrations; Instructional Materials; *Literary Devices; *Satire; Social Studies; United States History; Visual Aids; World History IDENTIFIERS *Political Cartoons ABSTRACT This essay focuses on the ability of the political cartoon to enhance history instruction. A trend in recent years is for social studies teachers to use these graphics to enhance instruction. Cartoons have the ability to:(1) empower teachers to demonstrate excellence during lessons; (2) prepare students for standardized tests containing cartoon questions;(3) promote critical thinking as in the Bradley Commission's suggestions for developing "History's Habits of the Mind;"(4) develop students' multiple intelligences, especially those of special needs learners; and (5) build lessons that aid students to master standards of governmental or professional curriculum organizations. The article traces the historical development of the political cartoon and provides examples of some of the earliest ones; the contemporary scene is also represented. Suggestions are given for use of research and critical thinking skills in interpreting editorial cartoons. The caricature and symbolism of political cartoons also are explored. An extensive reference section provides additional information and sources for political cartoons. -

David Alfaro Siqueiros Papers, 1921-1991, Bulk 1930-1936

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf9t1nb3n3 No online items Finding aid for the David Alfaro Siqueiros papers, 1921-1991, bulk 1930-1936 Annette Leddy Finding aid for the David Alfaro 960094 1 Siqueiros papers, 1921-1991, bulk 1930-1936 Descriptive Summary Title: David Alfaro Siqueiros papers Date (inclusive): 1920-1991 (bulk 1930-1936) Number: 960094 Creator/Collector: Siqueiros, David Alfaro Physical Description: 2.11 Linear Feet(6 boxes) Repository: The Getty Research Institute Special Collections 1200 Getty Center Drive, Suite 1100 Los Angeles 90049-1688 [email protected] URL: http://hdl.handle.net/10020/askref (310) 440-7390 Abstract: A leading member of the Mexican muralist movement and a technical innovator of fresco and wall painting. The collection consists almost entirely of manuscripts, some in many drafts, others fragmentary, the bulk of which date from the mid-1930s, when Siqueiros traveled to Los Angeles, New York, Buenos Aires, and Montevideo, returning intermittently to Mexico City. A significant portion of the papers concerns Siqueiros's public disputes with Diego Rivera; there are manifestos against Rivera, eye-witness accounts of their public debate, and newspaper coverage of the controversy. There is also material regarding the murals América Tropical, Mexico Actual and Ejercicio Plastico, including one drawing and a few photographs. The Experimental Workshop in New York City is also documented. Request Materials: Request access to the physical materials described in this inventory through the catalog record for this collection. Click here for the access policy . Language: Collection material is in Spanish; Castilian and English Biographical/Historical Note David Alfaro Siqueiros was a leading member of the Mexican muralist movement and a technical innovator of fresco and wall painting. -

Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) Case Log October 2000 - April 2002

Description of document: Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) Case Log October 2000 - April 2002 Requested date: 2002 Release date: 2003 Posted date: 08-February-2021 Source of document: Information and Privacy Coordinator Central Intelligence Agency Washington, DC 20505 Fax: 703-613-3007 Filing a FOIA Records Request Online The governmentattic.org web site (“the site”) is a First Amendment free speech web site and is noncommercial and free to the public. The site and materials made available on the site, such as this file, are for reference only. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals have made every effort to make this information as complete and as accurate as possible, however, there may be mistakes and omissions, both typographical and in content. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals shall have neither liability nor responsibility to any person or entity with respect to any loss or damage caused, or alleged to have been caused, directly or indirectly, by the information provided on the governmentattic.org web site or in this file. The public records published on the site were obtained from government agencies using proper legal channels. Each document is identified as to the source. Any concerns about the contents of the site should be directed to the agency originating the document in question. GovernmentAttic.org is not responsible for the contents of documents published on the website. 1 O ct 2000_30 April 2002 Creation Date Requester Last Name Case Subject 36802.28679 STRANEY TECHNOLOGICAL GROWTH OF INDIA; HONG KONG; CHINA AND WTO 36802.2992 CRAWFORD EIGHT DIFFERENT REQUESTS FOR REPORTS REGARDING CIA EMPLOYEES OR AGENTS 36802.43927 MONTAN EDWARD GRADY PARTIN 36802.44378 TAVAKOLI-NOURI STEPHEN FLACK GUNTHER 36810.54721 BISHOP SCIENCE OF IDENTITY FOUNDATION 36810.55028 KHEMANEY TI LEAF PRODUCTIONS, LTD. -

Anita Brenner

Premio Rabino Jacobo Goldberg 2015 Marcela López Arellano (Aguascalientes, El lector encontrará en esta obra la vida de la mujer que en su México). Es licenciada en Investigación época fue un modelo intelectual, polifacética y conocedora a Educativa por la Universidad Autónoma profundidad de dos culturas en las cuales estuvo inmersa: la de Aguascalientes, maestra en Estudios mexicana y la judía. Fue una mujer cuya presencia resultó Humanísticos/Historia por el Instituto trascendental para la historia del arte mexicano, así como la Tecnológico de Estudios Superiores de expresión de su judaísmo arraigado desde su infancia. La autora Monterrey, y doctora en Ciencias Sociales y logra penetrar en el ser y la conciencia de la gran escritora y Humanidades/Historia por la Universidad periodista Anita Brenner, a través de sus documentos personales Autónoma de Aguascalientes. como cartas, diarios y memorias, en cuyas letras se vislumbra la Ha publicado artículos y capítulos de li- visión que tuvo de México a lo largo de su vida. bros sobre la historia de Aguascalientes, historia de mujeres y de género y cultura escrita. Desde el año 2005 colabora sema- Marcela López Arellano fue distinguida con el Premio Rabino nalmente en un programa de radio/TV, en Jacobo Goldberg 2015, otorgado por la Comunidad Ashkenazí, el cual ha difundido sobre todo historia de A.C. de México, categoría Investigación. mujeres. Forma parte del Seminario de Me- moria Ciudadana CIESAS-INAH desde 2013, así como del Seminario de Historia de la Educación de la UAA con reconocimiento del SOMEHI- na escritora judía con México en el corazón DE. -

The Power and Politics of Art in Postrevolutionary Mexico'

H-LatAm Lopez on Smith, 'The Power and Politics of Art in Postrevolutionary Mexico' Review published on Friday, February 22, 2019 Stephanie J. Smith. The Power and Politics of Art in Postrevolutionary Mexico. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2017. 292 pp. $29.95 (paper), ISBN 978-1-4696-3568-2. Reviewed by Rick Lopez (Amherst College)Published on H-LatAm (February, 2019) Commissioned by Casey M. Lurtz (Johns Hopkins University) Printable Version: http://www.h-net.org/reviews/showpdf.php?id=52717 Stephanie Smith’s new book makes a welcome addition to the study of art and politics after the Mexico revolution. Her central argument is that even though Mexico’s leftist artists stridently disagreed with one other “on the exact nature of revolutionary art,” they “shared a common belief in the potential of art to be revolutionary,” and looked to the Mexican Communist Party (PCM) as the nexus through which they defined themselves as revolutionary artists. In contrast to Soviet social realist art, which fixated on “state figureheads,” Mexican social realism, with its distinctive emphasis on the masses and on organic intellectuals, gave leftists greater flexibility to publicly critique “the policies of the Mexican government” (p. 9). Smith seeks to understand how artists created this political space for action within postrevolutionary Mexico and the limitations of this flexibility. The book joins a growing body of literature that focuses on the intersections of art, politics, and culture that includes my own work as well as outstanding studies by such scholars as Mary Coffey, Adriana Zavala, Andrea Noble, and Mary Kay Vaughan. -

Epic of American Civilization Murals

NPS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 THE EPIC OF AMERICAN CIVILIZATION MURALS, BAKER LIBRARY Page 1 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 1. NAME OF PROPERTY Historic Name: The Epic of American Civilization Murals, Baker Library, Dartmouth College Other Name/Site Number: Baker-Berry Library 2. LOCATION Street & Number: 6025 Baker-Berry Library Not for publication: City/Town: Hanover Vicinity: State: NH County: Grafton Code: 009 Zip Code: 03755 3. CLASSIFICATION Ownership of Property Category of Property Private: X Building(s): _X_ Public-Local: District: ___ Public-State: ___ Site: ___ Public-Federal: ___ Structure: ___ Object: ___ Number of Resources within Property Contributing Noncontributing 1 buildings sites structures objects 1 Total Number of Contributing Resources Previously Listed in the National Register: Name of Related Multiple Property Listing: NPS Form 10-900 USDI/NPS NRHP Registration Form (Rev. 8-86) OMB No. 1024-0018 THE EPIC OF AMERICAN CIVILIZATION MURALS, BAKER LIBRARY Page 2 United States Department of the Interior, National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Registration Form 4. STATE/FEDERAL AGENCY CERTIFICATION As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, as amended, I hereby certify that this ____ nomination ____ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property ____ meets ____ does not meet the National Register Criteria. -

Vol. X. No.1 CONTENTS No Rights for Lynchers...• . . • 6

VoL. X. No.1 CONTENTS JANUARY 2, 19:34 No Rights for Lynchers. • . • 6 The New Republic vs. the Farmers •••••• 22 Roosevelt Tries Silver. 6 Books . .. .. • . • . • 24 Christmas Sell·Out ••••.......••..•.•••• , 7 An Open Letter by Granville Hicks ; Fascism in America, ••..• by John Strachey 8 Reviews by Bill Dunne, Stanley Burn shaw, Scott Nearing, Jack Conroy. The Reichstag Trial •• by Leonard L Mins 12 Doves in the Bull Ring .. by John Dos Passos 13 ·John Reed Club Art Exhibition ......... ' by Louis Lozowick 27 Is Pacifism Counter-Revolutionary ••••••• by J, B. Matthews 14 The Theatre •.•••... by William Gardener 28 The Big Hold~Up •••••••••••••••••••.•• 15 The Screen ••••••••••••• by Nathan Adler 28 Who Owns Congress •• by Marguerite Young 16 Music .................. by Ashley Pettis 29 Tom Mooney Walks at Midnight ••.••.•• Cover •••••• , ••••••• by William Gropper by Michael Gold 19 Other Drawinp by Art Young, Adolph The Farmen Form a United Front •••••• Dehn, Louis Ferstadt, Phil Bard, Mardi by Josephine Herbst 20 Gasner, Jacob Burck, Simeon Braguin. ......1'11 VOL, X, No.2 CONTENTS 1934 The Second Five~ Year Plan ........... , • 8 Books •••.•.••.••.•••••••••••••••••.••• 25 Writing and War ........ Henri Barbusse 10 A Letter to the Author of a First Book, by Michael Gold; Of the World Poisons for People ••••••••• Arthur Kallet 12 Revolution, by Granville Hicks; The Union Buttons in Philly ••••• Daniel Allen 14 Will Durant of Criticism, by Philip Rahv; Upton Sinclair's EPIC Dream, "Zafra Libre I" ••.••••..•• Harry Gannes 15 by William P. Mangold. A New Deal in Trusts .••• David Ramsey 17 End and Beginning .• Maxwell Bodenheim 27 Music • , • , •••••••••••••••. Ashley Pettis 28 The House on 16th Street ............. -

Magazines, Tourism, and Nation-Building in Mexico

STUDIES OF THE AMERICAS Series Editor: Maxine Molyneux MAGAZINES, TOURISM, AND NATION-BUILDING IN MEXICO Claire Lindsay Studies of the Americas Series Editor Maxine Molyneux Institute of the Americas University College London London, UK The Studies of the Americas Series includes country specifc, cross- disciplinary and comparative research on the United States, Latin America, the Caribbean, and Canada, particularly in the areas of Politics, Economics, History, Anthropology, Sociology, Anthropology, Development, Gender, Social Policy and the Environment. The series publishes monographs, readers on specifc themes and also welcomes proposals for edited collections, that allow exploration of a topic from several different disciplinary angles. This series is published in conjunc- tion with University College London’s Institute of the Americas under the editorship of Professor Maxine Molyneux. More information about this series at http://www.palgrave.com/gp/series/14462 Claire Lindsay Magazines, Tourism, and Nation-Building in Mexico Claire Lindsay Department of Spanish, Portuguese, and Latin American Studies University College London London, UK Studies of the Americas ISBN 978-3-030-01002-7 ISBN 978-3-030-01003-4 (eBook) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-01003-4 Library of Congress Control Number: 2018957069 © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2019. This book is an open access publication. Open Access This book is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license and indicate if changes were made. -

Disclaimer: the Opinions Expressed in This Review Are Those Of

Susannah Joel Glusker. Anita Brenner: A Mind of Her Own. Austin: University of Texas Press, 1998. xvi + 298 pp. $29.95, cloth, ISBN 978-0-292-72810-3. Reviewed by Charles C. Kolb Published on H-LatAm (April, 1999) Glusker, Anita Brenner's daughter, has writ‐ artists Jose Clemente Orozoco, David Alfaro ten an informative, fascinating, and lively biogra‐ Siqueiros, Miguel Covarrubias, and Henry Moore. phy of her mother, born as Hanna Brenner, to a She had a closer relationship with the illustrator Latvian-Jewish immigrant family in Aguas‐ Jean Charlot (he is characterized as "teacher, fa‐ calientes, Mexico on 13 August 1905. In the main, ther, and mentor") and Maria Sandoval de Zarco, this work covers the middle years of Brenner's then the only practicing woman lawyer in Mexico. life, 1920-1942. Brenner, educated in San Antonio, The poet Octavio Barreda and the writers Mari‐ Texas and New York City, would become an inde‐ ano Azuela, Carlos Fuentes, Lionel Trilling, pendent liberal, political radical, advocate of polit‐ Katherine Anne Porter, Frank Tannenbaum, John ical prisoners, and a champion of Mexican art and Dewey, and Miguel Unamuno were part of her culture. Some readers may recognize her as an life, as was the journalist Ernest Gruening (later historian, an anthropologist, a self-taught political Alaska's frst governor and U.S. Senator). In addi‐ journalist, a creative writer, or an art critic--she tion, political fgures such as Leon Trotsky, John was all of these and more. Anita Brenner num‐ and Alma Reed, and Whittaker Chambers; the bered among her friends many of the elite and in‐ photographer Edward Weston; cinema directors tellectuals of Mexico City and New York, among Sergei Eisenstein and Bud Schulberg; and the ar‐ them socialists, communists, poets, artists, and po‐ chaeologist-diplomat George C. -

Diego Rivera and the Left: the Destruction and Recreation of the Rockefeller Center Mural

Diego Rivera and the Left: The Destruction and Recreation of the Rockefeller Center Mural Dora Ape1 Diego Rivera, widely known for his murals at the Detroit Institute ofArts and the San Francisco Stock Exchange Luncheon Club, became famous nationally and internationally when his mural for the Radio City ofAmerica (RCA) Building at Rockefeller Center in New York City was halted on 9 May 1933, and subsequently destroyed on 10 February 1934. Commissioned at the height of the Depression and on the eve of Hitler's rise to power, Rivera's mural may be read as a response to the world's political and social crises, posing the alternatives for humanity as socialist harmony, represented by Lenin and scenes of celebration from the Soviet state, or capitalist barbarism, depicted through scenes of unemployment, war and "bourgeois decadence" in the form of drinking and gambling, though each side contained ambiguous elements. At the center stood contemporary man, the controller of nature and industrial power, whose choice lay between these two fates. The portrait of Lenin became the locus of the controversy at a moment when Rivera was disaffected with the policies of Stalin, and the Communist Party (CP) opposition was divided between Leon Trotsky and the international Left Opposition on one side, and the American Right Opposition led by Jay Lovestone on the other. In his mural, Rivera presented Lenin as the only historical figure who could clearly symbolize revolutionary political leadership. When he refused to remove the portrait of Lenin and substitute an anonymous face, as Nelson Rockefeller insisted, the painter was summarily dismissed, paid off, and the unfinished mural temporarily covered up, sparking a nationwide furor in both the left and capitalist press. -

Redalyc.Made for the USA: Orozco's Horrores De La Revolución

Anales del Instituto de Investigaciones Estéticas ISSN: 0185-1276 [email protected] Instituto de Investigaciones Estéticas México Indych, Anna Made for the USA: Orozco's Horrores de la Revolución Anales del Instituto de Investigaciones Estéticas, vol. XXIII, núm. 79, otoño, 2001, pp. 153-164 Instituto de Investigaciones Estéticas Distrito Federal, México Disponible en: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=36907905 Cómo citar el artículo Número completo Sistema de Información Científica Más información del artículo Red de Revistas Científicas de América Latina, el Caribe, España y Portugal Página de la revista en redalyc.org Proyecto académico sin fines de lucro, desarrollado bajo la iniciativa de acceso abierto ANNA INDYCH university of new york Made for the USA: Orozco’s Horrores de la Revolución1 hat seems to be the eternal violence of the civil war in Mexico spills out in the crude and raw, yet delicate ink and wash draw- Wings by José Clemente Orozco, known upon their commission as Horrores de la Revolución, and later, in the United States, entitled Mexico in Revolution. One of the lesser known works from the series, The Rape, in the collection of the Philadelphia Museum of Art, exemplifies Orozco’s horrific vision of the Revolution. In a ransacked room, a soldier mounts a half-naked woman, pinning her down to the floor by her arms and hair. He perpetuates a violation committed by the other figures leaving the room—one disheveled soldier, viewed from the back, lifts his pants to cover his rear as a shadowy figure exits through the parted curtains to the right of the drawing.