Diego Rivera and the Left: the Destruction and Recreation of the Rockefeller Center Mural

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Online Finding

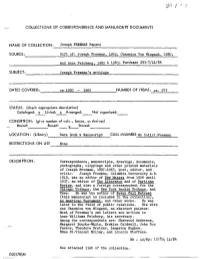

COLLECTIONS OF CORRESPONDENCE AND MANUSCRIPT DOCUMENTS NAME OF COLLECTION: Joseph FREEMAN Papers SOURCE: Gift of; Joseph Freeman, 1952; Charmion Von Wiegand, 1980; and Anne Feinberg, 1982 & 1983; Purchase 293-7/H/8U SUBJECT: Joseph Freeman's "writings DATES COVERED: ca.1920 - 1965 NUMBER OF ITEMS: ca. 675 STATUS: (check appropriate description) Cataloged: x Listed: x Arranged: Not organized: CONDITION: (give number of vols., boxes, or shelves) Bound: Boxed: o Stored: LOCATION: (Library) Rare Book & Manuscript CALL-NUMBER Ms Coll/J.Freeman RESTRICTIONS ON USE None DESCRIPTION: Correspondence, manuscripts, drawings, documents, photographs, clippings and other printed materials of Joseph Freeman, 1897-19&55 poet, editor, and critic. Joseph Freeman, Columbia University A.B. 1919» was an editor of New Masses from 1926 until 1937 j an editor of The Liberator and of Partisan Review, and also a foreign correspondent for the Chicago Tribune, the New York Herald Tribune, and Tass. He was the author of Never Call Retreat (this manuscript is included in the collection), An American Testament, and other works. He was later in the field of public relations. His wife was Charmion von Wiegand, an abstract painter. Most of Freeman's own letters are written to Anne Williams Feinberg, his secretary. Among the correspondents are: Sherwood Anderson, Margaret Bourke-White, Erskine Caldwell, John Dos Passos, Theodore Dreiser, Langston Hughes, Edna St.Vincent Millay, and Lincoln Steffens. HR - 12/82; 12/83; 11/8U See attached list of the collection. D3(178)M Joseph. Freeman Papers Box 1 Correspondence 8B misc. Cataloged correspondence & drawings: Anderson, Sherwood Harcourt, Alfred Bodenheim, Maxwell Herbst, Josephine Frey Bourke-White, Margaret Hughes, Langston Brown, Gladys Humphries, Rolfe Caldwell, Erskine Kent, Rockwell Dahlberg, Edward Komroff, Manuel Dehn, Adolph ^Millaf, Edna St. -

Home Sporting Events Featured Events & Shows by Venue

Metro Detroit Events: September - October 2017 Home Sporting Events DETROIT RED WINGS - LITTLE DETROT TIGERS - COMERICA CAESARS ARENA 66 Sibley St Detroit, MI 48201 PARK http://littlecaesars.arenadetroit.com 2100 Woodward Ave, Detroit (313) 962-4000 Sept 23 Preseason Wings vs Penguins 22-23 vs. Yankees Sept 25 Preseason Wings vs Penguins Sept 1-3 vs. Indians Sept 28 Preseason Wings vs. Sept 4-6 vs. Royals Blackhawks Sept 14-17 vs. White Sox Sept 29 Preseason Wings vs. Maple Sept 18- 20 vs. Athletics Leafs Sept 21-24 vs. Twins Oct 8 vs Minnesota Wild Oct 16 vs Tampa Bay Lightning DETROIT LIONS - FORD FIELD Oct 20 vs. Washington Capitals 2000 Brush St, Detroit (313) 262-2000 Oct 22 vs. Vancouver Canucks http://www.fordfield.com/ Oct 31 vs. Arizona Coyotes Sept 9 2017 Detroit Lions Season JIMMY JOHN’S FIELD Tickets 7171 Auburn Rd, Utica (248) 601-2400 Sept 10 vs. Arizona Cardinals https://uspbl.com/jimmy-johns-field/ Sept 24 vs. Atlanta Falcons Oct 8 vs. Carolina Panthers Sept 1 Westside vs Birmingham- Oct 29 vs. Pittsburg Steelers Bloomfield Sept 2 Eastside vs Westside MSU FOOTBALL Sept 3 Eastside vs Utica 325 W Shaw Ln, East Lansing (517) 355-1610 Sept 4 Birmingham- Bloomfield vs Utica http://www.msuspartans.com Sept 7 Westside vs Eastside Sept 8-10 2017 USPBL Playoffs Sept 2 Bowling Green Falcons Sept 9 Western Michigan Broncos Featured Events & Shows by Sept 23 Notre Dame Fighting Irish Venue Sept 30 Iowa Hawkeyes Oct 21 Indiana Hoosiers ANDIAMO CELEBRITY SHOWROOM 7096 E 14 Mile Road, Warren (586) 268-3200 U OF M FOOTBALL http://andiamoitalia.com/showroom/ 1201 S Main St, Ann Arbor (734) 647-2583 http://mgoblue.com/ Sept 22 Eva Evola Oct 13 Pasquate Esposito Sept 9 Cincinnati Bearcats Oct 20 Bridget Everett Sept 16 Air Force Falcons Oct 21 Peabo Bryson Oct 17 Michigan State Spartans Oct 28 Rutgers Scarlet Knights Do you have something we should add? Let us know! For additional news and happenings, follow Relevar Home Care on Facebook and LinkedIn. -

The Surgery Panel in Diego Rivera's Detroit

> The surgery panel in Diego Rivera’s Detroit Industry Murals The surgery panel in Diego Rivera’s Detroit Industry Murals The surgery panel in Diego Rivera’s Detroit Industry Murals The Surgery Panel. The surgeon performs an orchiectomy at center. The blood-stained drapes form a mound that is both a volcano and a pyramid, images seen at the top registers of the south and north walls of the courtyard. Arrays of organs surround the surgeon’s hands: base of brain with pituitary in center; digestive organs and endocrine glands to the left; male and female reproductive structures and breast to the right. Note the duodenum to the left; a pipe in the assembly line has the same configuration. Juxtaposition of female and male repro- ductive organs reflects the androgyny of the titans on the top registers of both walls. The wave motif signifies energy and is the dominating pattern in the middle register of both walls. Grey ropy material resembling semen flows from the left to form crystals on the right. Detroit Institute of Arts. Gift of Edsel B. Ford. Bridgeman Images. Don K. Nakayama, MD, MBA The author (AΩA, University of California, San Francisco, operation, because to his or her eye, it is an orchiectomy. Not 1978) is professor and chair of the Department of Surgery at the usual images in public art. West Virginia University School of Medicine. Why did Rivera include them in his work, the one that he considered his greatest effort?1 There are no direct quotes from asily overlooked, high in the upper left corner of the Rivera on the reasons for his choice of organs and operation. -

Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) Case Log October 2000 - April 2002

Description of document: Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) Case Log October 2000 - April 2002 Requested date: 2002 Release date: 2003 Posted date: 08-February-2021 Source of document: Information and Privacy Coordinator Central Intelligence Agency Washington, DC 20505 Fax: 703-613-3007 Filing a FOIA Records Request Online The governmentattic.org web site (“the site”) is a First Amendment free speech web site and is noncommercial and free to the public. The site and materials made available on the site, such as this file, are for reference only. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals have made every effort to make this information as complete and as accurate as possible, however, there may be mistakes and omissions, both typographical and in content. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals shall have neither liability nor responsibility to any person or entity with respect to any loss or damage caused, or alleged to have been caused, directly or indirectly, by the information provided on the governmentattic.org web site or in this file. The public records published on the site were obtained from government agencies using proper legal channels. Each document is identified as to the source. Any concerns about the contents of the site should be directed to the agency originating the document in question. GovernmentAttic.org is not responsible for the contents of documents published on the website. 1 O ct 2000_30 April 2002 Creation Date Requester Last Name Case Subject 36802.28679 STRANEY TECHNOLOGICAL GROWTH OF INDIA; HONG KONG; CHINA AND WTO 36802.2992 CRAWFORD EIGHT DIFFERENT REQUESTS FOR REPORTS REGARDING CIA EMPLOYEES OR AGENTS 36802.43927 MONTAN EDWARD GRADY PARTIN 36802.44378 TAVAKOLI-NOURI STEPHEN FLACK GUNTHER 36810.54721 BISHOP SCIENCE OF IDENTITY FOUNDATION 36810.55028 KHEMANEY TI LEAF PRODUCTIONS, LTD. -

UC Riverside UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UC Riverside UC Riverside Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Re-Conceptualizing Social Medicine in Diego Rivera's History of Medicine in Mexico: The People's Demand for Better Health Mural, Mexico City, 1953. Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/7038q9mk Author Gomez, Gabriela Rodriguez Publication Date 2012 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE Re-Conceptualizing Social Medicine in Diego Rivera's History of Medicine in Mexico: The People's Demand for Better Health Mural, Mexico City, 1953. A Thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Art History by Gabriela Rodriguez-Gomez June 2012 Thesis Committee: Dr. Jason Weems, Chairperson Dr. Liz Kotz Dr. Karl Taube Copyright by Gabriela Rodriguez-Gomez 2012 The Thesis of Gabriela Rodriguez-Gomez is approved: ___________________________________ ___________________________________ ___________________________________ Committee Chairperson University of California Riverside Acknowledgements I dedicate my thesis research to all who influenced both its early and later developments. Travel opportunities for further research were made possible by The Graduate Division at UC Riverside, The University of California Humanities Research Institute, and the Rupert Costo Fellowship for Native American Scholarship. I express my humble gratitude to my thesis committee, Art History Professors Jason Weems (Chair), Liz Kotz, and Professor of Anthropology Karl Taube. The knowledge, insight, and guidance you all have given me throughout my research has been memorable. A special thanks (un agradecimiento inmenso) to; Tony Gomez III, Mama, Papa, Ramz, The UCR Department of Art History, Professor of Native North American History Cliff Trafzer, El Instituto Seguro Social de Mexico (IMSS) - Sala de Prensa Directora Patricia Serrano Cabadas, Coordinadora Gloria Bermudez Espinosa, Coordinador de Educación Dr. -

Vol. X. No.1 CONTENTS No Rights for Lynchers...• . . • 6

VoL. X. No.1 CONTENTS JANUARY 2, 19:34 No Rights for Lynchers. • . • 6 The New Republic vs. the Farmers •••••• 22 Roosevelt Tries Silver. 6 Books . .. .. • . • . • 24 Christmas Sell·Out ••••.......••..•.•••• , 7 An Open Letter by Granville Hicks ; Fascism in America, ••..• by John Strachey 8 Reviews by Bill Dunne, Stanley Burn shaw, Scott Nearing, Jack Conroy. The Reichstag Trial •• by Leonard L Mins 12 Doves in the Bull Ring .. by John Dos Passos 13 ·John Reed Club Art Exhibition ......... ' by Louis Lozowick 27 Is Pacifism Counter-Revolutionary ••••••• by J, B. Matthews 14 The Theatre •.•••... by William Gardener 28 The Big Hold~Up •••••••••••••••••••.•• 15 The Screen ••••••••••••• by Nathan Adler 28 Who Owns Congress •• by Marguerite Young 16 Music .................. by Ashley Pettis 29 Tom Mooney Walks at Midnight ••.••.•• Cover •••••• , ••••••• by William Gropper by Michael Gold 19 Other Drawinp by Art Young, Adolph The Farmen Form a United Front •••••• Dehn, Louis Ferstadt, Phil Bard, Mardi by Josephine Herbst 20 Gasner, Jacob Burck, Simeon Braguin. ......1'11 VOL, X, No.2 CONTENTS 1934 The Second Five~ Year Plan ........... , • 8 Books •••.•.••.••.•••••••••••••••••.••• 25 Writing and War ........ Henri Barbusse 10 A Letter to the Author of a First Book, by Michael Gold; Of the World Poisons for People ••••••••• Arthur Kallet 12 Revolution, by Granville Hicks; The Union Buttons in Philly ••••• Daniel Allen 14 Will Durant of Criticism, by Philip Rahv; Upton Sinclair's EPIC Dream, "Zafra Libre I" ••.••••..•• Harry Gannes 15 by William P. Mangold. A New Deal in Trusts .••• David Ramsey 17 End and Beginning .• Maxwell Bodenheim 27 Music • , • , •••••••••••••••. Ashley Pettis 28 The House on 16th Street ............. -

Finding Aid Prepared by David Kennaly Washington, D.C

THE LIBRARY OF CONGRESS RARE BOOK AND SPECIAL COLLECTIONS DIVISION THE RADICAL PAMPHLET COLLECTION Finding aid prepared by David Kennaly Washington, D.C. - Library of Congress - 1995 LIBRARY OF CONGRESS RARE BOOK ANtI SPECIAL COLLECTIONS DIVISIONS RADICAL PAMPHLET COLLECTIONS The Radical Pamphlet Collection was acquired by the Library of Congress through purchase and exchange between 1977—81. Linear feet of shelf space occupied: 25 Number of items: Approx: 3465 Scope and Contents Note The Radical Pamphlet Collection spans the years 1870-1980 but is especially rich in the 1930-49 period. The collection includes pamphlets, newspapers, periodicals, broadsides, posters, cartoons, sheet music, and prints relating primarily to American communism, socialism, and anarchism. The largest part deals with the operations of the Communist Party, USA (CPUSA), its members, and various “front” organizations. Pamphlets chronicle the early development of the Party; the factional disputes of the 1920s between the Fosterites and the Lovestoneites; the Stalinization of the Party; the Popular Front; the united front against fascism; and the government investigation of the Communist Party in the post-World War Two period. Many of the pamphlets relate to the unsuccessful presidential campaigns of CP leaders Earl Browder and William Z. Foster. Earl Browder, party leader be—tween 1929—46, ran for President in 1936, 1940 and 1944; William Z. Foster, party leader between 1923—29, ran for President in 1928 and 1932. Pamphlets written by Browder and Foster in the l930s exemplify the Party’s desire to recruit the unemployed during the Great Depression by emphasizing social welfare programs and an isolationist foreign policy. -

The Life and Works of Philip J. Jaffe: a Foreigner's Foray

THE LIFE AND WORKS OF PHILIP J. JAFFE: A FOREIGNER’S FORAY INTO CHINESE COMMUNISM Patrick Nichols “…the capitalist world is divided into two rival sectors, the one in favor of peace and the status quo, and the other the Fascist aggressors and provokers of a new world war.” These words spoken by Mao Tse Tung to Philip J. Jaffe in a confidential interview. Although China has long held international relations within its Asian sphere of influence, the introduction of a significant Western persuasion following their defeats in the Opium Wars was the first instance in which China had been subservient to the desires of foreigners. With the institution of a highly westernized and open trading policy per the wishes of the British, China had lost the luster of its dynastic splendor and had deteriorated into little more than a colony of Western powers. Nevertheless, as China entered the 20th century, an age of new political ideologies and institutions began to flourish. When the Kuomintang finally succeeded in wrestling control of the nation from the hands of the northern warlords following the Northern Expedition1, it signaled a modern approach to democratizing China. However, as the course of Chinese political history will show, the KMT was a morally weak ruling body that appeased the imperial intentions of the Japanese at the cost of Chinese citizens and failed to truly assert its political legitimacy during it‟s almost ten year reign. Under these conditions, a radical and highly determined sect began to form within the KMT along with foreign assistance. The party held firmly on the idea of general welfare, but focused mostly on the rights of the working class and student nationalists. -

American Communists View Mexican Muralism: Critical and Artistic Responses1

AMERICAN COMMUNISTS VIEW MEXICAN MURALISM: CRITICAL AND ARTISTIC RESPONSES1 Andrew Hemingway A basic presupposition of this essay is 1My thanks to Jay Oles for his helpful cri- that the influence of Mexican muralism ticisms of an earlier version of this essay. on some American artists of the inter- While the influence of Commu- war period was fundamentally related nism among American writers of the to the attraction many of these same so-called "Red Decade" of the 1930s artists felt towards Communism. I do is well-known and has been analysed not intend to imply some simple nec- in a succession of major studies, its essary correlation here, but, given the impact on workers in the visual arts revolutionary connotations of the best- is less well understood and still under- known murals and the well-publicized estimated.3 This is partly because the Marxist views of two of Los Tres Grandes, it was likely that the appeal of this new 2I do not, of course, mean to discount artistic model would be most profound the influence of Mexican muralism on non-lef- among leftists and aspirant revolutionar- tists such as George Biddle and James Michael ies.2 To map the full impact of Mexican Newell. For Biddle on the Mexican example, see his 'Mural Painting in America', Magazine of Art, muralism among such artists would be vol. 27, no. 7, July 1934, pp.366-8; An American a major task, and one I can not under- Artist's Story, Boston, Little, Brown and Company, take in a brief essay such as this. -

The American Communist Movement Underwent Several Splits in Its Early Years

Index Note: The American Communist movement underwent several splits in its early years. When uni- fied in the early 1920s, it was first called the Workers’ Party and then the Workers’ (Communist) Party; in 1929 it became the Communist Party, USA. This work uses the term Communist Party (CP) to describe the party from 1922 on, and references are indexed in a single category here. [However there were other, distinct organizations with similar names; there are separate index entries for the Communist Party of America (1919–21), the Communist Labor Party (1919–20), the United Communist Party (1920–1) and the Communist League of America (Opposition) (1928–34).] ABB See African Blood Brotherhood American Federation of Labor (AFL) Abd el-Krim 325 and FFLP 124, 126 Abern, Martin 138n2, 139n1, 156, 169–170, and immigrant workers 76, 107, 193 209n2, 212n, 220n2, 252n, 259–260, 262 and IWW 88, 92 ACWA See Amalgamated Clothing Workers and Passaic strike 190–193, 195–197 AFL See American Federation of Labor and Profintern 87, 91–92 Africa 296, , 298–299, 304–308, 313–317, 323, and TUEL 106–108, 118 325–327, 331–332, 342–346, 355, 357, 361, and women workers 193 363n2 anti-Communism 21, 83, 91, 112, 125–126, French colonies 313, 325 148, 191, 193, 196, 210, 284, 324, 326 See also pan-Africanism; South Africa anti-strike activity 193 African Americans See blacks, American bureaucracy 75n2, 106, 118, 211, 215, 284 African Blood Brotherhood (ABB) 23, bureaucracy, racism of 102, 306, 324, 298–304, 306, 312, 317, 322–324, 343 326–327, 330 See also Briggs Comintern on 21, 83–84, 87, 91–92, 109, African sailors, Communist work among 317 210, 256, 285 agricultural workers, Communist work Communist work in 14, 21, 75–76, 83, 85, among 95, 287, 323, 326, 340, 348, 360n3 115, 215 Alabama 5, 11, 348, 360n3, 362, 363n1 dissent within 75, 100, 108, 113 See also Scottsboro Boys expulsion of Communists 110, 125–126, All-American Anti-Imperialist League 187, 149, 196–197 331–332 Foster in 98, 100–102, 106–107, 109, Allen, James S. -

Detroit Media Guide Contents

DETROIT MEDIA GUIDE CONTENTS EXPERIENCE THE D 1 Welcome ..................................................................... 2 Detroit Basics ............................................................. 3 New Developments in The D ................................. 4 Destination Detroit ................................................... 9 Made in The D ...........................................................11 Fast Facts ................................................................... 12 Famous Detroiters .................................................. 14 EXPLORE DETROIT 15 The Detroit Experience...........................................17 Dearborn/Wayne ....................................................20 Downtown Detroit ..................................................22 Greater Novi .............................................................26 Macomb ....................................................................28 Oakland .....................................................................30 Itineraries .................................................................. 32 Annual Events ..........................................................34 STAYING WITH US 35 Accommodations (by District) ............................. 35 NAVIGATING THE D 39 Metro Detroit Map ..................................................40 Driving Distances ....................................................42 District Maps ............................................................43 Transportation .........................................................48 -

The Left in the United States and the Decline of the Socialist Party of America, 1934–1935 Jacob A

Document généré le 1 oct. 2021 11:01 Labour Journal of Canadian Labour Studies Le Travail Revue d’Études Ouvrières Canadiennes The Left in the United States and the Decline of the Socialist Party of America, 1934–1935 Jacob A. Zumoff Volume 85, printemps 2020 Résumé de l'article Dans les premières années de la Grande Dépression, le Parti socialiste URI : https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1070907ar américain a attiré des jeunes et des intellectuels de gauche en même temps DOI : https://doi.org/10.1353/llt.2020.0006 qu’il était confronté au défi de se distinguer du Parti démocrate de Franklin D. Roosevelt. En 1936, alors que sa direction historique de droite (la «vieille Aller au sommaire du numéro garde») quittait le Parti socialiste américain et que bon nombre des membres les plus à gauche du Parti socialiste américain avaient décampé, le parti a perdu de sa vigueur. Cet article examine les luttes internes au sein du Partie Éditeur(s) socialiste américain entre la vieille garde et les groupements «militants» de gauche et analyse la réaction des groupes à gauche du Parti socialiste Canadian Committee on Labour History américain, en particulier le Parti communiste pro-Moscou et les partisans de Trotsky et Boukharine qui ont été organisés en deux petits groupes, le Parti ISSN communiste (opposition) et le Parti des travailleurs. 0700-3862 (imprimé) 1911-4842 (numérique) Découvrir la revue Citer cet article Zumoff, J. (2020). The Left in the United States and the Decline of the Socialist Party of America, 1934–1935. Labour / Le Travail, 85, 165–198.