Dictatorsh I P and Democracy Soviet Union

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Online Finding

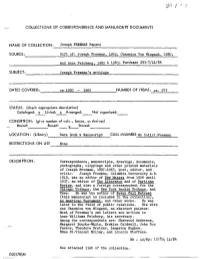

COLLECTIONS OF CORRESPONDENCE AND MANUSCRIPT DOCUMENTS NAME OF COLLECTION: Joseph FREEMAN Papers SOURCE: Gift of; Joseph Freeman, 1952; Charmion Von Wiegand, 1980; and Anne Feinberg, 1982 & 1983; Purchase 293-7/H/8U SUBJECT: Joseph Freeman's "writings DATES COVERED: ca.1920 - 1965 NUMBER OF ITEMS: ca. 675 STATUS: (check appropriate description) Cataloged: x Listed: x Arranged: Not organized: CONDITION: (give number of vols., boxes, or shelves) Bound: Boxed: o Stored: LOCATION: (Library) Rare Book & Manuscript CALL-NUMBER Ms Coll/J.Freeman RESTRICTIONS ON USE None DESCRIPTION: Correspondence, manuscripts, drawings, documents, photographs, clippings and other printed materials of Joseph Freeman, 1897-19&55 poet, editor, and critic. Joseph Freeman, Columbia University A.B. 1919» was an editor of New Masses from 1926 until 1937 j an editor of The Liberator and of Partisan Review, and also a foreign correspondent for the Chicago Tribune, the New York Herald Tribune, and Tass. He was the author of Never Call Retreat (this manuscript is included in the collection), An American Testament, and other works. He was later in the field of public relations. His wife was Charmion von Wiegand, an abstract painter. Most of Freeman's own letters are written to Anne Williams Feinberg, his secretary. Among the correspondents are: Sherwood Anderson, Margaret Bourke-White, Erskine Caldwell, John Dos Passos, Theodore Dreiser, Langston Hughes, Edna St.Vincent Millay, and Lincoln Steffens. HR - 12/82; 12/83; 11/8U See attached list of the collection. D3(178)M Joseph. Freeman Papers Box 1 Correspondence 8B misc. Cataloged correspondence & drawings: Anderson, Sherwood Harcourt, Alfred Bodenheim, Maxwell Herbst, Josephine Frey Bourke-White, Margaret Hughes, Langston Brown, Gladys Humphries, Rolfe Caldwell, Erskine Kent, Rockwell Dahlberg, Edward Komroff, Manuel Dehn, Adolph ^Millaf, Edna St. -

Red Press: Radical Print Culture from St

Red Press: Radical Print Culture from St. Petersburg to Chicago Pamphlets Explanatory Power I 6 fDK246.S2 M. Dobrov Chto takoe burzhuaziia? [What is the Bourgeoisie?] Petrograd: Petrogr. Torg. Prom. Soiuz, tip. “Kopeika,” 1917 Samuel N. Harper Political Pamphlets H 39 fDK246.S2 S.K. Neslukhovskii Chto takoe sotsializm? [What is Socialism?] Petrograd: K-vo “Svobodnyi put’”, [n.d.] Samuel N. Harper Political Pamphlets H 10 fDK246.S2 Aleksandra Kollontai Kto takie sotsial-demokraty i chego oni khotiat’? [Who Are the Social Democrats and What Do They Want?] Petrograd: Izdatel’stvo i sklad “Kniga,” 1917 Samuel N. Harper Political Pamphlets I 7 fDK246.S2 Vatin (V. A. Bystrianskii) Chto takoe kommuna? (What is a Commune?) Petrograd: Petrogradskogo Soveta Rabochikh i Krasnoarmeiskikh Deputatov, 1918 Samuel N. Harper Political Pamphlets E 32 fDK246.S2 L. Kin Chto takoe respublika? [What is a Republic?] Petrograd: Revoliutsionnaia biblioteka, 1917 Samuel N. Harper Political Pamphlets E 31 fDK246.S2 G.K. Kryzhitskii Chto takoe federativnaia respublika? (Rossiiskaia federatsiia) [What is a Federal Republic? (The Russian Federation)] Petrograd: Znamenskaia skoropechatnaia, 1917 1 Samuel N. Harper Political Pamphlets E42 fDK246.S2 O.A. Vol’kenshtein (Ol’govich): Federalizm v Rossii [Federalism in Russia] Knigoizdatel’stvo “Luch”, [n.d.] fDK246.S2 E33 I.N. Ignatov Gosudarstvennyi stroi Severo-Amerikanskikh Soedinenykh shtatov: Respublika [The Form of Government of the United States of America: Republic] Moscow: t-vo I. D. Sytina, 1917 fDK246.S2 E34 K. Parchevskii Polozhenie prezidenta v demokraticheskoi respublike [The Position of the President in a Democratic Republic] Petrograd: Rassvet, 1917 fDK246.S2 H35 Prof. V.V. -

Vol. X. No.1 CONTENTS No Rights for Lynchers...• . . • 6

VoL. X. No.1 CONTENTS JANUARY 2, 19:34 No Rights for Lynchers. • . • 6 The New Republic vs. the Farmers •••••• 22 Roosevelt Tries Silver. 6 Books . .. .. • . • . • 24 Christmas Sell·Out ••••.......••..•.•••• , 7 An Open Letter by Granville Hicks ; Fascism in America, ••..• by John Strachey 8 Reviews by Bill Dunne, Stanley Burn shaw, Scott Nearing, Jack Conroy. The Reichstag Trial •• by Leonard L Mins 12 Doves in the Bull Ring .. by John Dos Passos 13 ·John Reed Club Art Exhibition ......... ' by Louis Lozowick 27 Is Pacifism Counter-Revolutionary ••••••• by J, B. Matthews 14 The Theatre •.•••... by William Gardener 28 The Big Hold~Up •••••••••••••••••••.•• 15 The Screen ••••••••••••• by Nathan Adler 28 Who Owns Congress •• by Marguerite Young 16 Music .................. by Ashley Pettis 29 Tom Mooney Walks at Midnight ••.••.•• Cover •••••• , ••••••• by William Gropper by Michael Gold 19 Other Drawinp by Art Young, Adolph The Farmen Form a United Front •••••• Dehn, Louis Ferstadt, Phil Bard, Mardi by Josephine Herbst 20 Gasner, Jacob Burck, Simeon Braguin. ......1'11 VOL, X, No.2 CONTENTS 1934 The Second Five~ Year Plan ........... , • 8 Books •••.•.••.••.•••••••••••••••••.••• 25 Writing and War ........ Henri Barbusse 10 A Letter to the Author of a First Book, by Michael Gold; Of the World Poisons for People ••••••••• Arthur Kallet 12 Revolution, by Granville Hicks; The Union Buttons in Philly ••••• Daniel Allen 14 Will Durant of Criticism, by Philip Rahv; Upton Sinclair's EPIC Dream, "Zafra Libre I" ••.••••..•• Harry Gannes 15 by William P. Mangold. A New Deal in Trusts .••• David Ramsey 17 End and Beginning .• Maxwell Bodenheim 27 Music • , • , •••••••••••••••. Ashley Pettis 28 The House on 16th Street ............. -

House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC)

Cold War PS MB 10/27/03 8:28 PM Page 146 House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC) Excerpt from “One Hundred Things You Should Know About Communism in the U.S.A.” Reprinted from Thirty Years of Treason: Excerpts From Hearings Before the House Committee on Un-American Activities, 1938–1968, published in 1971 “[Question:] Why ne Hundred Things You Should Know About Commu- shouldn’t I turn “O nism in the U.S.A.” was the first in a series of pam- Communist? [Answer:] phlets put out by the House Un-American Activities Commit- You know what the United tee (HUAC) to educate the American public about communism in the United States. In May 1938, U.S. represen- States is like today. If you tative Martin Dies (1900–1972) of Texas managed to get his fa- want it exactly the vorite House committee, HUAC, funded. It had been inactive opposite, you should turn since 1930. The HUAC was charged with investigation of sub- Communist. But before versive activities that posed a threat to the U.S. government. you do, remember you will lose your independence, With the HUAC revived, Dies claimed to have gath- ered knowledge that communists were in labor unions, gov- your property, and your ernment agencies, and African American groups. Without freedom of mind. You will ever knowing why they were charged, many individuals lost gain only a risky their jobs. In 1940, Congress passed the Alien Registration membership in a Act, known as the Smith Act. The act made it illegal for an conspiracy which is individual to be a member of any organization that support- ruthless, godless, and ed a violent overthrow of the U.S. -

Diego Rivera and the Left: the Destruction and Recreation of the Rockefeller Center Mural

Diego Rivera and the Left: The Destruction and Recreation of the Rockefeller Center Mural Dora Ape1 Diego Rivera, widely known for his murals at the Detroit Institute ofArts and the San Francisco Stock Exchange Luncheon Club, became famous nationally and internationally when his mural for the Radio City ofAmerica (RCA) Building at Rockefeller Center in New York City was halted on 9 May 1933, and subsequently destroyed on 10 February 1934. Commissioned at the height of the Depression and on the eve of Hitler's rise to power, Rivera's mural may be read as a response to the world's political and social crises, posing the alternatives for humanity as socialist harmony, represented by Lenin and scenes of celebration from the Soviet state, or capitalist barbarism, depicted through scenes of unemployment, war and "bourgeois decadence" in the form of drinking and gambling, though each side contained ambiguous elements. At the center stood contemporary man, the controller of nature and industrial power, whose choice lay between these two fates. The portrait of Lenin became the locus of the controversy at a moment when Rivera was disaffected with the policies of Stalin, and the Communist Party (CP) opposition was divided between Leon Trotsky and the international Left Opposition on one side, and the American Right Opposition led by Jay Lovestone on the other. In his mural, Rivera presented Lenin as the only historical figure who could clearly symbolize revolutionary political leadership. When he refused to remove the portrait of Lenin and substitute an anonymous face, as Nelson Rockefeller insisted, the painter was summarily dismissed, paid off, and the unfinished mural temporarily covered up, sparking a nationwide furor in both the left and capitalist press. -

Social Bonds, Sexual Politics, and Political Community on the U.S. Left, 1920S-1940S' Kathleen A

Social Bonds, Sexual Politics, and Political Community on the U.S. Left, 1920s-1940s' Kathleen A. Brown and Elizabeth Faue William Armistead Nelson Collier, a sometime anarchist and poet, self- professed free lover and political revolutionary, inhabited a world on the "lunatic fringe" of the American Left. Between the years 1908 and 1948, he traversed the legitimate and illegitimate boundaries of American radicalism. After escaping commitment to an asylum, Collier lived in several cooperative colonies - Upton Sinclair's Helicon Hall, the Single Tax Colony in Fairhope, Alabama, and April Farm in Pennsylvania. He married (three times legally) andor had sexual relationships with a number of radical women, and traveled the United States and Europe as the Johnny Appleseed of Non-Monogamy. After years of dabbling in anarchism and communism, Collier came to understand himself as a radical individualist. He sought social justice for the proletariat more in the realm of spiritual and sexual life than in material struggle.* Bearded, crude, abrupt and fractious, Collier was hardly the model of twentieth century American radicalism. His lover, Francoise Delisle, later wrote of him, "The most smarting discovery .. was that he was only a dilettante, who remained on the outskirts of the left wing movement, an idler and loafer, flirting with it, in search of amorous affairs, and contributing nothing of value, not even a hard day's work."3 Most historians of the 20th century Left would share Delisle's disdain. Seeking to change society by changing the intimate relations on which it was built, Collier was a compatriot, they would argue, not of William Z. -

Download Original 7.82 MB

WELLESLEY COLLEGE BULLETIN ANNUAL REPORTS PRESIDENT AND TREASURER ^^ 191 6= J 8 WELLESLEY, MASSACHUSETTS DECEMBER, I9I8 PUBLISHED BY THE COLLEGE IN JANUARY, MAY, JUNE, NOVEMBER, DECEMBER Entered as second-class matter December 20, 1911, at the post-office at Wellesley. Massachusetts, under Act of Congress of July 16, 1894. SERIES 7 NUMBER 6 WELLESLEY COLLEGE ANNUAL EEPOKTS PBESIDENT AND TREASURER 1916-1918 PRESIDENT'S ANNUAL REPORT To the Board of Trustees of Wellesley College:— I have the honor to present in one the report of the two years from July 1, 1916, to June 30, 1918. Heretofore the annual reports of the President and Treasurer due June 30 have been published in the following March. It was decided to publish these hereafter in December. To avoid publishing two reports in the 1918 series, the report for 1916-17 was de- layed, and is here combined with that for 1917-18. The sup- plementary reports of the Dean, the Librarian, and the Chair- man of the Committee on Graduate Instruction will also cover two years. These two years have brought many losses to the College. On February 12, 1917, Pauline Adeline Durant, the widow of the founder of the College, died at her home in Wellesley. Mrs. Durant gave the heartiest co-operation to Mr. Durant's plan for founding the College, and throughout his life assisted him in every way. After his death in October, 1881, she accepted the care of the College as a sacred trust from her husband, and gave to it thought, time, and money. Mrs. Durant had been an invalid confined to her home for more than three years before her death, but until these later years no meeting of the Board of Trustees nor any college function was complete without her presence. -

American Communists View Mexican Muralism: Critical and Artistic Responses1

AMERICAN COMMUNISTS VIEW MEXICAN MURALISM: CRITICAL AND ARTISTIC RESPONSES1 Andrew Hemingway A basic presupposition of this essay is 1My thanks to Jay Oles for his helpful cri- that the influence of Mexican muralism ticisms of an earlier version of this essay. on some American artists of the inter- While the influence of Commu- war period was fundamentally related nism among American writers of the to the attraction many of these same so-called "Red Decade" of the 1930s artists felt towards Communism. I do is well-known and has been analysed not intend to imply some simple nec- in a succession of major studies, its essary correlation here, but, given the impact on workers in the visual arts revolutionary connotations of the best- is less well understood and still under- known murals and the well-publicized estimated.3 This is partly because the Marxist views of two of Los Tres Grandes, it was likely that the appeal of this new 2I do not, of course, mean to discount artistic model would be most profound the influence of Mexican muralism on non-lef- among leftists and aspirant revolutionar- tists such as George Biddle and James Michael ies.2 To map the full impact of Mexican Newell. For Biddle on the Mexican example, see his 'Mural Painting in America', Magazine of Art, muralism among such artists would be vol. 27, no. 7, July 1934, pp.366-8; An American a major task, and one I can not under- Artist's Story, Boston, Little, Brown and Company, take in a brief essay such as this. -

New- MASSES •• •• MAY, %9Z6

NEw- MASSES •• MAY, %9Z6 IS THIS IT? IN THIS ISSUE Is this the magazine our prospectuses THE WRITERS talked about? We are not so sure. This, BABETTE DEUTSCH, winner however, is undoubtedly the editorial which, of this year's "Nation" Poetry Prize, in all our prospectuses, we promised faith has published two volumes of poetry. fully not to write. She has recently visited Soviet Russia. As to the magazine, we regard it with ROBERT DlJNN is the author of "Ameri· almost complete detachment and a good deal can Foreign Investments" and co-author with of critical interest, because we didn"t make Sidney Howard of it ourselves. "The Labor Spy." ROBINSON JEFFERS' "Roan Stallion, We merely "discovered"" it. Tamar and Other Poems," published last We were confident that somewhere in year, established him as one of the impor• America a NEW MASSES existed, if only as tant contemporary American poets, He live. a frustrated desire. in Carmel, Calif. To materialize it, all that was needed was WILLIAM CARLOS WILLIAMS is well to make a certain number of prosaic editorial known as physician, modernist, poet and motions. story-writer, and is the author of "In the American Crain... We made the motions, material poured in, and we sent our first issue to the printer. NATHAN ASCH is the author of a collec tion of vivid short stories published last Next month we shall make, experimentally, year under the title, "The Office." He slightly different lives motions, and a somewhat in Paris. different NEW MASSES will blossom pro fanely on the news-stands in the midst of NORMAN STUDER Ia one of the editors our respectable contemporaries, the whiz of the "New Student." bangs,. -

1947 Reprint No Number 28 Pp

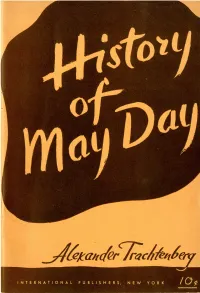

HISTORY OF MAY DAY BY ALEXANDER TRACHTENBERG INTERNATIONAL PUBLISHERS NEW YORK NOTE History of May Day was first published in 1929 aJild was re issued in many editions, reaching a circulation of over a quarter million copies. It is now published in a revised edition. Copyright, 1947, by INTERNATIONAL PUBLISHERS CO., INC • ..... 209 PRINTED IN U.S.A. HISTORY OF MAY DAY THE ORIGIN OF MAY DAY is indissolubly bound up with the struggle for the shorter workday-a demand of major political significance for the working class. This struggle is manifest almost from the beginning of the factory system in the United States. Although the demand for higher wages appears to be the most prevalent cause for the early strikes in this country, the question of shorter hours and the right to organize were always kept in the foreground when workers formulated their demands. As exploita tion was becoming intensified and workers were feeling more and more the strain of inhumanly long working hours, the demand for an appreciable reduction of hours became more pronounced. Already at the opening of the 19th century, workers in the United States made known their grievances against working from "sunrise to sunset," the then prevailing workday. Fourteen, six teen and even eighteen hours a day were not uncommon. During the conspiracy trial against the leaders of striking Philadelphia cordwainers in 1806, it was brought out that workers were em ployed as long as nineteen and twenty hours a day. The twenties and thirties are replete with strikes for reduction of hours of work and definite demands for a 10-hour day were put forward in many industrial centers. -

Representations in the Inter-War Years of the American White Working Class by Four Female Authors Paul Ha

1 The Story Less Told: Representations in the Inter-War Years of the American White Working Class by Four Female Authors Paul Harper A thesis submitted for the degree of MPhil in Literature Department of Literature, Film and Theatre Studies University of Essex March 2017 2 Contents - Abstract p. 4 - 1: Introduction p. 5 Thesis Outline The Authors to be Studied Social and Historical Context - 2: Terminology and Concepts p. 31 Working class Sex and Gender Women’s Writing The Male Gaze Propaganda Propaganda and Art Proletarian Art - 3. Anzia Yezierska p. 55 Yezierska’s Life Yezierska’s Style Yezierska’s Conclusions: An ‘American’ Author: Bread Givers, Arrogant Beggar, and Salome of the Tenements Salome of the Tenements Presentations of Sonya in Salome of the Tenements Conclusion - 4. Fielding Burke p. 95 Burke’s Life Burke’s Style Call Home the Heart and A Stone Came Rolling 3 Presentations of Ishma in Call Home the Heart and A Stone Came Rolling Conclusion - 5. Grace Lumpkin p. 129 Lumpkin’s Life Lumpkin’s Shifting Perspective: Analysis focused on The Wedding and Full Circle Lumpkin’s 1930s Proletarian Novels: A Sign for Cain and To Make My Bread Conclusion - 6. Myra Page p. 173 Page’s Life The Feminist Theme in Page’s ‘Other’ 1930s Novels: Moscow Yankee & Daughter of the Hills Gathering Storm Conclusion - 7. Conclusion p. 209 - Bibliography p. 217 4 Abstract This thesis will study novels written in the interwar years by four female authors: Anzia Yezierska, Fielding Burke, Grace Lumpkin, and Myra Page. While a general overview of these authors’ biographies, writing styles, themes, and approaches to issues surrounding race and religion will be provided, the thesis’ main focuses are as follows: studying the way in which the authors treat gender through their representation of working-class women; exploring the interaction between art and propaganda in their novels; and considering the extent to which their backgrounds and life experiences influence their writing. -

“To Work, Write, Sing and Fight for Women's Liberation”

“To work, write, sing and fight for women’s liberation” Proto-Feminist Currents in the American Left, 1946-1961 Shirley Chen A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of BACHELOR OF SCIENCE WITH HONORS DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY UNIVERSITY OF MICHIGAN March 30, 2011 Advised by Professor Howard Brick For my mother Table of Contents Acknowledgements .......................................................................................................... ii Introduction...................................................................................................................... 1 Chapter I: “An End to the Neglect” ............................................................................ 10 Progressive Women & the Communist Left, 1946-1953 Chapter II: “A Woman’s Place is Wherever She Wants it to Be” ........................... 44 Woman as Revolutionary in Marxist-Humanist Thought, 1950-1956 Chapter III: “Are Housewives Necessary?” ............................................................... 73 Old Radicals & New Radicalisms, 1954-1961 Conclusion .................................................................................................................... 106 Bibliography ................................................................................................................. 111 Acknowledgements First, I am deeply grateful to my adviser, Professor Howard Brick. From helping me formulate the research questions for this project more than a year ago to reading last minute drafts, his