From Confession to Exposure Transitions in 1940S Anticommunist Literature Alex Goodall

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Online Finding

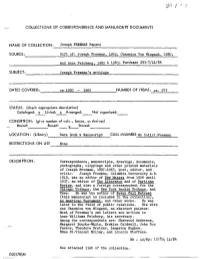

COLLECTIONS OF CORRESPONDENCE AND MANUSCRIPT DOCUMENTS NAME OF COLLECTION: Joseph FREEMAN Papers SOURCE: Gift of; Joseph Freeman, 1952; Charmion Von Wiegand, 1980; and Anne Feinberg, 1982 & 1983; Purchase 293-7/H/8U SUBJECT: Joseph Freeman's "writings DATES COVERED: ca.1920 - 1965 NUMBER OF ITEMS: ca. 675 STATUS: (check appropriate description) Cataloged: x Listed: x Arranged: Not organized: CONDITION: (give number of vols., boxes, or shelves) Bound: Boxed: o Stored: LOCATION: (Library) Rare Book & Manuscript CALL-NUMBER Ms Coll/J.Freeman RESTRICTIONS ON USE None DESCRIPTION: Correspondence, manuscripts, drawings, documents, photographs, clippings and other printed materials of Joseph Freeman, 1897-19&55 poet, editor, and critic. Joseph Freeman, Columbia University A.B. 1919» was an editor of New Masses from 1926 until 1937 j an editor of The Liberator and of Partisan Review, and also a foreign correspondent for the Chicago Tribune, the New York Herald Tribune, and Tass. He was the author of Never Call Retreat (this manuscript is included in the collection), An American Testament, and other works. He was later in the field of public relations. His wife was Charmion von Wiegand, an abstract painter. Most of Freeman's own letters are written to Anne Williams Feinberg, his secretary. Among the correspondents are: Sherwood Anderson, Margaret Bourke-White, Erskine Caldwell, John Dos Passos, Theodore Dreiser, Langston Hughes, Edna St.Vincent Millay, and Lincoln Steffens. HR - 12/82; 12/83; 11/8U See attached list of the collection. D3(178)M Joseph. Freeman Papers Box 1 Correspondence 8B misc. Cataloged correspondence & drawings: Anderson, Sherwood Harcourt, Alfred Bodenheim, Maxwell Herbst, Josephine Frey Bourke-White, Margaret Hughes, Langston Brown, Gladys Humphries, Rolfe Caldwell, Erskine Kent, Rockwell Dahlberg, Edward Komroff, Manuel Dehn, Adolph ^Millaf, Edna St. -

Snoring As a Fine Art and Twelve Other Essays

SNORING AS A FINE ART AND TWELVE OTHER ESSAYS By Albert Jay Nock RICHARD R. SMITH PUBLISHER, INC. Rindge, New Hampshire 1958 Copyright, © 1958 By- Francis Jay Nock Published By Richard R. Smith Publisher, Inc. Topside, West Rindge, N. H. Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 57-10363 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be repro- duced in any form without permission of the publisher. Printed in U. S. A. by The Colonial Press Inc. These Essays were selected in memory of Albert Jay Nock by his friends of many years Ruth Robinson Ellen Winsor Rebecca Winsor Evans ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Permission to reprint the essays herein has been graciously granted by the original copyright owners specified below. Since publication, however, the ownership of the several copyrights has been trans- ferred to the author's son, Dr. Francis Jay Nock. The American Mercury: What the American Votes For. February 1933 The Atlantic Monthly: If Only— August 1937 Sunday in Brussels. September 1938 Snoring As a Fine Art. November 1938 The Purpose of Biography. March 1940 Epstean's Law. October 1940 Utopia in Pennsylvania: The Amish. April 1941 The Bookman: Bret Harte as a Parodist. May 1929 Harper's Magazine: Alas! Poor Yorick! June 1929 The King's Jester: Modern Style. March 1928 Scribner's Magazine: Henry George: Unorthodox American. November 1933 Life, Liberty, And— March 1935 The Seivanee Review: Advertising and Liberal Literature. Winter 1918 iii CONTENTS Page Introduction By Suzanne La Follette Snoring As A Fine Art And the Claims of General M. I. Kutusov As an Artist i Life, Liberty, And .. -

Rethinking the Historiography of United States Communism: Questioning American Radicalism*

chapter 7 Rethinking the Historiography of United States Communism: Questioning American Radicalism* We ask questions of radicalism in the United States. Many on the left and amongst historians researching and writing about its past are driven by high expectations and preconceived notions of what such radicalism should look like. Our queries reflect this: Why is there no socialism in America? Why are workers in the world’s most advanced capitalist nation not ‘class con- scious’? Why has no ‘third party’ of labouring people emerged to challenge the established political formations of money, privilege and business power? Such interrogation is by no means altogether wrong-headed, although some would prefer to jettison it entirely. Yet these and other related questions continue to exercise considerable interest, and periodically spark debate and efforts to reformulate and redefine analytic agendas for the study of American labour radicals, their diversity, ideas and practical activities.1 Socialism, syndicalism, anarchism and communism have been minority traditions in us life, just as they often are in other national cultures and political economies. The revolu- tionary left is, and always has been, a vanguard of minorities. But minorit- ies often make history, if seldom in ways that prove to be exactly as they pleased. Life in a minority is not, however, an isolated, or inevitably isolating, exper- ience. In the late 19th and early 20th centuries the us gave rise to a signific- ant left, rooted in what many felt was a transition from the -

The Modern Hardboiled Detective in the Novella Form

Utah State University DigitalCommons@USU All Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate Studies 5-2015 "We want to get down to the nitty-gritty": The Modern Hardboiled Detective in the Novella Form Kendall G. Pack Utah State University Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd Part of the English Language and Literature Commons Recommended Citation Pack, Kendall G., ""We want to get down to the nitty-gritty": The Modern Hardboiled Detective in the Novella Form" (2015). All Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 4247. https://digitalcommons.usu.edu/etd/4247 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate Studies at DigitalCommons@USU. It has been accepted for inclusion in All Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@USU. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “WE WANT TO GET DOWN TO THE NITTY-GRITTY”: THE MODERN HARDBOILED DETECTIVE IN THE NOVELLA FORM by Kendall G. Pack A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE in English (Literature and Writing) Approved: ____________________________ ____________________________ Charles Waugh Brian McCuskey Major Professor Committee Member ____________________________ ____________________________ Benjamin Gunsberg Mark McLellan Committee Member Vice President for Research and Dean of the School of Graduate Studies UTAH STATE UNIVERSITY Logan, Utah 2015 ii Copyright © Kendall Pack 2015 All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT “We want to get down to the nitty-gritty”: The Modern Hardboiled Detective in the Novella Form by Kendall G. Pack, Master of Science Utah State University, 2015 Major Professor: Dr. Charles Waugh Department: English This thesis approaches the issue of the detective in the 21st century through the parodic novella form. -

Vol. X. No.1 CONTENTS No Rights for Lynchers...• . . • 6

VoL. X. No.1 CONTENTS JANUARY 2, 19:34 No Rights for Lynchers. • . • 6 The New Republic vs. the Farmers •••••• 22 Roosevelt Tries Silver. 6 Books . .. .. • . • . • 24 Christmas Sell·Out ••••.......••..•.•••• , 7 An Open Letter by Granville Hicks ; Fascism in America, ••..• by John Strachey 8 Reviews by Bill Dunne, Stanley Burn shaw, Scott Nearing, Jack Conroy. The Reichstag Trial •• by Leonard L Mins 12 Doves in the Bull Ring .. by John Dos Passos 13 ·John Reed Club Art Exhibition ......... ' by Louis Lozowick 27 Is Pacifism Counter-Revolutionary ••••••• by J, B. Matthews 14 The Theatre •.•••... by William Gardener 28 The Big Hold~Up •••••••••••••••••••.•• 15 The Screen ••••••••••••• by Nathan Adler 28 Who Owns Congress •• by Marguerite Young 16 Music .................. by Ashley Pettis 29 Tom Mooney Walks at Midnight ••.••.•• Cover •••••• , ••••••• by William Gropper by Michael Gold 19 Other Drawinp by Art Young, Adolph The Farmen Form a United Front •••••• Dehn, Louis Ferstadt, Phil Bard, Mardi by Josephine Herbst 20 Gasner, Jacob Burck, Simeon Braguin. ......1'11 VOL, X, No.2 CONTENTS 1934 The Second Five~ Year Plan ........... , • 8 Books •••.•.••.••.•••••••••••••••••.••• 25 Writing and War ........ Henri Barbusse 10 A Letter to the Author of a First Book, by Michael Gold; Of the World Poisons for People ••••••••• Arthur Kallet 12 Revolution, by Granville Hicks; The Union Buttons in Philly ••••• Daniel Allen 14 Will Durant of Criticism, by Philip Rahv; Upton Sinclair's EPIC Dream, "Zafra Libre I" ••.••••..•• Harry Gannes 15 by William P. Mangold. A New Deal in Trusts .••• David Ramsey 17 End and Beginning .• Maxwell Bodenheim 27 Music • , • , •••••••••••••••. Ashley Pettis 28 The House on 16th Street ............. -

The Road to Serfdom

F. A. Hayek The Road to Serfdom ~ \ L f () : I~ ~ London and New York ( m v ..<I S 5 \ First published 1944 by George Routledge & Sons First published in Routledge Classics 2001 by Routledge 2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, OX14 4 RN 270 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016 Repri nted 2001, 2002, 2003, 2004, 2006 Routledge is an imprint ofthe Taylor CJ( Francis Group, an informa business © 1944 F. A. Hayek Typeset in Joanna by RefineCatch Limited, Bungay, Suffolk Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ International Ltd, Padstow, Cornwall All rights reserved. No part ofthis book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library ISBN 10: 0-415-25543-0 (hbk) ISBN 10: 0-415-25389-6 (pbk) ISBN 13: 978-0-415-25543-1 (hbk) ISBN 13: 978-0-415-25389-5 (pbk) CONTENTS PREFACE vii Introduction 1 The Abandoned Road 10 2 The Great Utopia 24 3 Individualism and Collectivism 33 4 The "Inevitability" of Planning 45 5 Planning and Democracy 59 6 Planning and the Rule of Law 75 7 Economic Control and Totalitarianism 91 8 Who, Whom? 1°5 9 Security and Freedom 123 10 Why the Worst Get on Top 138 11 The End ofTruth 157 12 The Socialist Roots of Nazism 171 13 The Totalitarians in our Midst 186 14 Material Conditions and Ideal Ends 207 15 The Prospects of International Order 225 2 THE GREAT UTOPIA What has always made the state a hell on earth has been precisely that man has tried to make it his heaven. -

EVAN HUNTER / ED Mcbain

MICKEY SPILLANE, 1918-2006 On March 9, 1918, in Brooklyn, New York, Frank Morrison Spillane was born on March 9, 1918, in Brooklyn, to parents Anne and John Spillane. Although he would be known as Morrison by his teachers, it was his father's nickname for him which would endure: Mickey. As a youth, he excelled at football and swimming. It was during his high school years that he began his writing career, with his first piece published shortly after graduation. Early in his career, he would often have his work published under pseudonyms, Frank Morrison being one of them. After high school, he briefly attended Kansas State Teachers College, spending most of his time there playing football. After college, he returned to New York. He worked at Gimbel's then joined the staff of writers at Marvel Comic Books, penning detective and supehero stories. When WW II broke out, Mickey enlisted in the Air Force but remained stateside and out of the action. Stationed in Mississippi, he met Mary Ann Pearce, who, in 1945, became his first wife. They later had four children, Kathy, Ward, Michael and Caroline. After the war, he returned to New York. He bought a plot of land and decided to build a new home on it. To do so required a thousand dollars, a thousand dollars more than he had. So, in order to raise the money, he decided to write a book. He based it on a comic book character called Mike Danger he had created early in his career. That book was I, The Jury. -

Is the Market a Test of Truth and Beauty Essays in Political

Is the Market a Test of Truth and Beauty? Is the Market a Test of TRUTH BEAUTY? Essays in Political Economy by L B. Y Ludwig von Mises Institute © 2011 by the Ludwig von Mises Institute and published under the Creative Commons Attribution License 3.0. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/ Ludwig von Mises Institute 518 West Magnolia Avenue Auburn, Alabama 36832 mises.org ISBN: 978-1-61016-188-6 Contents Introduction . vii : Should Austrians Scorn General Equilibrium eory? . Why Subjectivism? ..................... Henry George and Austrian Economics ........... e Debate about the Efficiency of a Socialist Economy . e Debate over Calculation and Knowledge ......... Austrian Economics, Neoclassicism, and the Market Test . Is the Market a Test of Truth and Beauty? . Macroeconomics and Coordination . e Keynesian Heritage in Economics . Hutt and Keynes ....................... e Image of the Gold Standard . Land, Money, and Capital Formation . Tacit Preachments are the Worst Kind . Tautologies in Economics and the Natural Sciences . : Free Will and Ethics . Elementos del Economia Politic . Is ere a Bias Toward Overregulation? . Economics and Principles .................. American Democracy Diagnosed . Civic Religion Reasserted . A Libertarian Case for Monarchy . v vi Contents Uchronia, or Alternative History . Hayek on the Psychology of Socialism and Freedom . Kirzner on the Morality of Capitalist Profit . Mises and His Critics on Ethics, Rights, and Law . e Moral Element in Mises’s Human Action . Can a Liberal Be an Egalitarian? ............... Rights, Contract, and Utility in Policy Espousal . Index ............................... Introduction Tis book’s title is the same as the newly chosen title of chapter , “Is the Market a Test of Truth and Beauty?” Tat chapter, along with the one before it, questions a dangerously false argument for the free-market economy sometimes made by its supposed friends. -

Kiss Me Deadly by Alain Silver

Kiss Me Deadly By Alain Silver “A savage lyricism hurls us into a world in full decomposition, ruled by the dissolute and the cruel,” wrote Raymond Borde and Etienne Chaumeton about “Kiss Me Deadly” in their seminal study “Panorama du Film Noir Américain.” “To these violent and corrupt intrigues, Aldrich brings the most radical of solutions: nuclear apoca- lypse.” From the beginning, “Kiss Me Deadly” is a true sensory explosion. In the pre- credit sequence writer A.I. Bezzerides and producer/director Robert Aldrich introduce Christina (Cloris Leachman), a woman in a trench coat, who stumbles out of the pitch darkness onto a two-lane blacktop. While her breathing fills the soundtrack with am- plified, staccato gasps, blurred metallic shapes flash by without stopping. She posi- tions herself in the center of the roadway until oncoming headlights blind her with the harsh glare of their high beams. Brakes grab, tires scream across the asphalt, and a Jaguar spins off the highway in a swirl of dust. A close shot reveals Mike Hammer Robert Aldrich on the set of "Attack" in 1956 poses with the first (Ralph Meeker) behind the wheel: over the edition of "Panorama of American Film Noir." Photograph sounds of her panting and jazz on the car ra- courtesy Adell Aldrich. dio. The ignition grinds repeatedly as he tries to restart the engine. Finally, he snarls at her, satisfaction of the novel into a blacker, more sardon- “You almost wrecked my car! Well? Get in!” ic disdain for the world in general, the character be- comes a cipher for all the unsavory denizens of the For pulp novelist Mickey Spillane, Hammer's very film noir underworld. -

Rex Stout Does Not Belong in Russia: Exporting the Detective Novel

Wesleyan University The Honors College Rex Stout Does Not Belong in Russia: Exporting the Detective Novel by Molly Jane Levine Zuckerman Class of 2016 A thesis submitted to the faculty of Wesleyan University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Arts with Departmental Honors in the Russian, East European, and Eurasian Studies Program Middletown, Connecticut April, 2016 Foreword While browsing through a stack of Russian and American novels in translation on a table on Arbat Street in Moscow in 2013, I came across a Russian copy of one of my favorite books, And Be a Villain, by one of my favorite authors, Rex Stout. I only knew about this author because my father had lent me a copy of And Be a Villain when I was in middle school, and I was so entranced by the novel that I went out to Barnes & Noble to buy as many as they had in stock. I quickly ran out of Stout books to read, because at the time, his books were out of print in America. I managed to get hold of most copies by high school, courtesy of a family friend’s mother who had died and passed on her collection of Stout novels to our family. Due to the relative difficulty I had had in acquiring these books in America, I was surprised to find one lying on a book stand in Moscow, so I bought it for less than 30 cents (which was probably around the original price of its first printing in America). -

Kiss Me Deadly Nephew of John D

March 13, 2001 (III:8) ROBERT ALDRICH (9 August 1918, Cranston, Rhode Island – 5 December 1983, Los Angeles, kidney failure), a Kiss Me Deadly nephew of John D. Rockefeller, Jr., and cousin of New 1955, 106 minutes, York’s quondam governor, worked as an assistant director Parklane Pictures to Chaplin and Renoir before becoming a director himself. He is one of those directors whose films are more likely to Director Robert Aldrich turn up on critics’ Secret Pleasures lists than their Grand Script by A.I Bezzerides, based on = Films lists. He directed 31 films, among them All the Marbles Mickey Spillane s novel 1981, The Choirboys 1977, Twilight's Last Gleaming 1977, Producer Robert Aldrich Hustle 1975, The Longest Yard 1974, The Killing of Sister Original music Frank De Vol George 1968, The Dirty Dozen 1967, Hush... Hush, Sweet Cinematographer Ernest Laszlo Charlotte 1964, What Ever Happened to Baby Jane? 1962, The Film Editor Michael Luciano Big Knife 1955, Apache 1954, and Vera Cruz 1954. Art Director William Glasgow Ralph Meeker Mike Hammer ERNEST LASZLO (23 April 1898 – 6 January 1984, Hollywood) was a cinematographer for 50 years, beginning with The Pace that Kills 1928 and ending Albert Dekker Dr. G.E. Soberin with The Domino Principle 1977. He shot 66 other films, among them Logan's Run Paul Stewart Carl Evello 1976, Airport 1970, Star! 1968, Luv 1967, Fantastic Voyage 1966, Baby the Rain Must Juano Hernandez Eddie Yeager Fall 1965, Ship of Fools 1965, It's a Mad Mad Mad Mad World 1963, Judgment at Wesley Addy Pat Chambers Nuremberg 1961, Inherit the Wind 1960, The Big Knife 1955, The Kentuckian 1955, Gaby Rogers Lily Carver Apache 1954, The Naked Jungle 1954, Vera Cruz 1954, Stalag 17 1953, The Moon Is Blue Marian Carr Friday 1953, D.O.A. -

{PDF EPUB} the First Rex Stout Omnibus Featuring Nero

Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} The First Rex Stout Omnibus Featuring Nero Wolfe And Archie Goodwin The Doorbell Rang The Second The First Rex Stout Omnibus: Featuring Nero Wolfe And Archie Goodwin: " The Doorbell Rang " " The Second Confession " And " More Deaths Than One " by Rex Stout. TimeSearch for Books and Writers by Bamber Gascoigne. American author, who wrote over 70 detective novels, 46 of them featuring eccentric, chubby, beer drinking gourmet sleuth Nero Wolfe, whose wisecracking aide and right hand assistant in crime solving was Archie Goodwin. Stout began his literary career by writing for pulp magazines, publishing romance, adventure, some borderline detective stories. After 1938 he focused solely on the mystery field. Rex Stout was born in Noblesville, Indiana, the son of John Wallace Stout and Lucetta Elizabeth Todhunter. They both were Quakers. Shortly after his birth, the family moved to Wakarusa, Kansas. Stout was educated at Topeka High School, and at University of Kansas, Lawrence, which he left to enlist in the Navy. From 1906 to 1908 he served as a Yeoman on President Theodore Roosevelt's yacht. The following years Stout spent writing freelance articles and working in odd jobs – as an office boy, store clerk, bookkeeper, and hotel manager. With his brother he invented an astonishing savings plans, the Educational Thrift Service, for school children. The system was installed in 400 cities throughout the USA, earning Stout about $400,000 and making him financially secure. In 1916 Stout married Fay Kennedy of Topeka, Kansas. They separated in 1931 – according to a story, she eloped with a Russian commissar – and Stout married Pola Hoffman, a fabric designer.