Alexander Gumberg and Soviet-American Relations: 1917–1933

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Catherine the Great and the Development of a Modern Russian Sovereignty, 1762-1796

Catherine the Great and the Development of a Modern Russian Sovereignty, 1762-1796 By Thomas Lucius Lowish A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Victoria Frede-Montemayor, Chair Professor Jonathan Sheehan Professor Kinch Hoekstra Spring 2021 Abstract Catherine the Great and the Development of a Modern Russian Sovereignty, 1762-1796 by Thomas Lucius Lowish Doctor of Philosophy in History University of California, Berkeley Professor Victoria Frede-Montemayor, Chair Historians of Russian monarchy have avoided the concept of sovereignty, choosing instead to describe how monarchs sought power, authority, or legitimacy. This dissertation, which centers on Catherine the Great, the empress of Russia between 1762 and 1796, takes on the concept of sovereignty as the exercise of supreme and untrammeled power, considered legitimate, and shows why sovereignty was itself the major desideratum. Sovereignty expressed parity with Western rulers, but it would allow Russian monarchs to bring order to their vast domain and to meaningfully govern the lives of their multitudinous subjects. This dissertation argues that Catherine the Great was a crucial figure in this process. Perceiving the confusion and disorder in how her predecessors exercised power, she recognized that sovereignty required both strong and consistent procedures as well as substantial collaboration with the broadest possible number of stakeholders. This was a modern conception of sovereignty, designed to regulate the swelling mechanisms of the Russian state. Catherine established her system through careful management of both her own activities and the institutions and servitors that she saw as integral to the system. -

The Suppression of Jewish Culture by the Soviet Union's Emigration

\\server05\productn\B\BIN\23-1\BIN104.txt unknown Seq: 1 18-JUL-05 11:26 A STRUGGLE TO PRESERVE ETHNIC IDENTITY: THE SUPPRESSION OF JEWISH CULTURE BY THE SOVIET UNION’S EMIGRATION POLICY BETWEEN 1945-1985 I. SOCIAL AND CULTURAL STATUS OF JEWS IN THE SOVIET SOCIETY BEFORE AND AFTER THE WAR .................. 159 R II. BEFORE THE BORDERS WERE CLOSED: SOVIET EMIGRATION POLICY UNDER STALIN (1945-1947) ......... 163 R III. CLOSING OF THE BORDER: CESSATION OF JEWISH EMIGRATION UNDER STALIN’S REGIME .................... 166 R IV. THE STRUGGLE CONTINUES: SOVIET EMIGRATION POLICY UNDER KHRUSHCHEV AND BREZHNEV .................... 168 R V. CONCLUSION .............................................. 174 R I. SOCIAL AND CULTURAL STATUS OF JEWS IN THE SOVIET SOCIETY BEFORE AND AFTER THE WAR Despite undergoing numerous revisions, neither the Soviet Constitu- tion nor the Soviet Criminal Code ever adopted any laws or regulations that openly or implicitly permitted persecution of or discrimination against members of any minority group.1 On the surface, the laws were always structured to promote and protect equality of rights and status for more than one hundred different ethnic groups. Since November 15, 1917, a resolution issued by the Second All-Russia Congress of the Sovi- ets called for the “revoking of all and every national and national-relig- ious privilege and restriction.”2 The Congress also expressly recognized “the right of the peoples of Russia to free self-determination up to seces- sion and the formation of an independent state.” Identical resolutions were later adopted by each of the 15 Soviet Republics. Furthermore, Article 124 of the 1936 (Stalin-revised) Constitution stated that “[f]reedom of religious worship and freedom of anti-religious propaganda is recognized for all citizens.” 3 1 See generally W.E. -

St. Petersburg Case Study

250 i\R(HITE<TLIKE: MATERIAL AND IMAGINED Re-forming Architecture and Planning through Urban Design: St. Petersburg Case Study MATTHEW J. BELL University of Maryland INTRODUCTION the city. The program was also designed to appeal to upper- level graduate architecture and planning students and to Political changes in the former Soviet Union have had a sornehow synthesize the traditional concerns of each of those concurrent effect upon the physical landscape of the cities of disciplines: the physical fonn of the city in the case of the that country. Some cities have seen the invasion, for lack of architects; and the problems and in a sense 'fonn' of the city a better way to describe conditions, of capitalism and the from a social and econolnic view in the case of the planning subsequent frenzy of speculative building activity in the st~dents.~ fonn of new office buildings and the explosion of retail centers. Most of this building activity has been confined to HISTORY OF THE SITE Moscow which, because of differences in regional laws and statutes, has been the most aggressive place in seeking new St. Petersburg was founded on the banks of the Neva River development. by Peter the Great in 1703 on one of the most unlikely of In contrast to the exploding development scene in Mos- places, a low lying, swampy area, many miles north of the cow, the czarist capital of St. Petersburg has seen relatively centers of Russian population. Peter established the city in little new construction and a dearth of almost any building order to counter the claims of the Swedish crown to the Gulf activity in its central district. -

Division I Men's Outdoor Track Championships Records Book

DIVISION I MEN’S OUTDOOR TRACK CHAMPIONSHIPS RECORDS BOOK 2020 Championship 2 History 2 All-Time Team Results 30 2020 CHAMPIONSHIP The 2020 championship was not contested due to the COVID-19 pandemic. HISTORY TEAM RESULTS (Note: No meet held in 1924.) †Indicates fraction of a point. *Unofficial champion. Year Champion Coach Points Runner-Up Points Host or Site 1921 Illinois Harry Gill 20¼ Notre Dame 16¾ Chicago 1922 California Walter Christie 28½ Penn St. 19½ Chicago 1923 Michigan Stephen Farrell 29½ Mississippi St. 16 Chicago 1925 *Stanford R.L. Templeton 31† Chicago 1926 *Southern California Dean Cromwell 27† Chicago 1927 *Illinois Harry Gill 35† Chicago 1928 Stanford R.L. Templeton 72 Ohio St. 31 Chicago 1929 Ohio St. Frank Castleman 50 Washington 42 Chicago 22 1930 Southern California Dean Cromwell 55 ⁄70 Washington 40 Chicago 1 1 1931 Southern California Dean Cromwell 77 ⁄7 Ohio St. 31 ⁄7 Chicago 1932 Indiana Billy Hayes 56 Ohio St. 49¾ Chicago 1933 LSU Bernie Moore 58 Southern California 54 Chicago 7 1934 Stanford R.L. Templeton 63 Southern California 54 ⁄20 Southern California 1935 Southern California Dean Cromwell 741/5 Ohio St. 401/5 California 1936 Southern California Dean Cromwell 103⅓ Ohio St. 73 Chicago 1937 Southern California Dean Cromwell 62 Stanford 50 California 1938 Southern California Dean Cromwell 67¾ Stanford 38 Minnesota 1939 Southern California Dean Cromwell 86 Stanford 44¾ Southern California 1940 Southern California Dean Cromwell 47 Stanford 28⅔ Minnesota 1941 Southern California Dean Cromwell 81½ Indiana 50 Stanford 1 1942 Southern California Dean Cromwell 85½ Ohio St. 44 ⁄5 Nebraska 1943 Southern California Dean Cromwell 46 California 39 Northwestern 1944 Illinois Leo Johnson 79 Notre Dame 43 Marquette 3 1945 Navy E.J. -

Online Finding

COLLECTIONS OF CORRESPONDENCE AND MANUSCRIPT DOCUMENTS NAME OF COLLECTION: Joseph FREEMAN Papers SOURCE: Gift of; Joseph Freeman, 1952; Charmion Von Wiegand, 1980; and Anne Feinberg, 1982 & 1983; Purchase 293-7/H/8U SUBJECT: Joseph Freeman's "writings DATES COVERED: ca.1920 - 1965 NUMBER OF ITEMS: ca. 675 STATUS: (check appropriate description) Cataloged: x Listed: x Arranged: Not organized: CONDITION: (give number of vols., boxes, or shelves) Bound: Boxed: o Stored: LOCATION: (Library) Rare Book & Manuscript CALL-NUMBER Ms Coll/J.Freeman RESTRICTIONS ON USE None DESCRIPTION: Correspondence, manuscripts, drawings, documents, photographs, clippings and other printed materials of Joseph Freeman, 1897-19&55 poet, editor, and critic. Joseph Freeman, Columbia University A.B. 1919» was an editor of New Masses from 1926 until 1937 j an editor of The Liberator and of Partisan Review, and also a foreign correspondent for the Chicago Tribune, the New York Herald Tribune, and Tass. He was the author of Never Call Retreat (this manuscript is included in the collection), An American Testament, and other works. He was later in the field of public relations. His wife was Charmion von Wiegand, an abstract painter. Most of Freeman's own letters are written to Anne Williams Feinberg, his secretary. Among the correspondents are: Sherwood Anderson, Margaret Bourke-White, Erskine Caldwell, John Dos Passos, Theodore Dreiser, Langston Hughes, Edna St.Vincent Millay, and Lincoln Steffens. HR - 12/82; 12/83; 11/8U See attached list of the collection. D3(178)M Joseph. Freeman Papers Box 1 Correspondence 8B misc. Cataloged correspondence & drawings: Anderson, Sherwood Harcourt, Alfred Bodenheim, Maxwell Herbst, Josephine Frey Bourke-White, Margaret Hughes, Langston Brown, Gladys Humphries, Rolfe Caldwell, Erskine Kent, Rockwell Dahlberg, Edward Komroff, Manuel Dehn, Adolph ^Millaf, Edna St. -

Meat: a Novel

University of New Hampshire University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository Faculty Publications 2019 Meat: A Novel Sergey Belyaev Boris Pilnyak Ronald D. LeBlanc University of New Hampshire, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/faculty_pubs Recommended Citation Belyaev, Sergey; Pilnyak, Boris; and LeBlanc, Ronald D., "Meat: A Novel" (2019). Faculty Publications. 650. https://scholars.unh.edu/faculty_pubs/650 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Faculty Publications by an authorized administrator of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Sergey Belyaev and Boris Pilnyak Meat: A Novel Translated by Ronald D. LeBlanc Table of Contents Acknowledgments . III Note on Translation & Transliteration . IV Meat: A Novel: Text and Context . V Meat: A Novel: Part I . 1 Meat: A Novel: Part II . 56 Meat: A Novel: Part III . 98 Memorandum from the Authors . 157 II Acknowledgments I wish to thank the several friends and colleagues who provided me with assistance, advice, and support during the course of my work on this translation project, especially those who helped me to identify some of the exotic culinary items that are mentioned in the opening section of Part I. They include Lynn Visson, Darra Goldstein, Joyce Toomre, and Viktor Konstantinovich Lanchikov. Valuable translation help with tricky grammatical constructions and idiomatic expressions was provided by Dwight and Liya Roesch, both while they were in Moscow serving as interpreters for the State Department and since their return stateside. -

Boris Pasternak - Poems

Classic Poetry Series Boris Pasternak - poems - Publication Date: 2012 Publisher: Poemhunter.com - The World's Poetry Archive Boris Pasternak(10 February 1890 - 30 May 1960) Boris Leonidovich Pasternak was a Russian language poet, novelist, and literary translator. In his native Russia, Pasternak's anthology My Sister Life, is one of the most influential collections ever published in the Russian language. Furthermore, Pasternak's theatrical translations of Goethe, Schiller, Pedro Calderón de la Barca, and William Shakespeare remain deeply popular with Russian audiences. Outside Russia, Pasternak is best known for authoring Doctor Zhivago, a novel which spans the last years of Czarist Russia and the earliest days of the Soviet Union. Banned in the USSR, Doctor Zhivago was smuggled to Milan and published in 1957. Pasternak was awarded the Nobel Prize for Literature the following year, an event which both humiliated and enraged the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. In the midst of a massive campaign against him by both the KGB and the Union of Soviet Writers, Pasternak reluctantly agreed to decline the Prize. In his resignation letter to the Nobel Committee, Pasternak stated the reaction of the Soviet State was the only reason for his decision. By the time of his death from lung cancer in 1960, the campaign against Pasternak had severely damaged the international credibility of the U.S.S.R. He remains a major figure in Russian literature to this day. Furthermore, tactics pioneered by Pasternak were later continued, expanded, and refined by Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn and other Soviet dissidents. <b>Early Life</b> Pasternak was born in Moscow on 10 February, (Gregorian), 1890 (Julian 29 January) into a wealthy Russian Jewish family which had been received into the Russian Orthodox Church. -

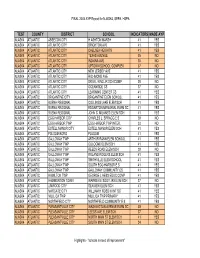

AYP 2003 Final Overall List

FINAL 2003 AYP Report for NJASK4, GEPA, HSPA TEST COUNTY DISTRICT SCHOOL INDICATORSMADE AYP NJASK4 ATLANTIC ABSECON CITY H ASHTON MARSH 41 YES NJASK4 ATLANTIC ATLANTIC CITY BRIGHTON AVE 41 YES NJASK4 ATLANTIC ATLANTIC CITY CHELSEA HEIGHTS 41 YES NJASK4 ATLANTIC ATLANTIC CITY TEXAS AVENUE 35 NO NJASK4 ATLANTIC ATLANTIC CITY INDIANA AVE 35 NO NJASK4 ATLANTIC ATLANTIC CITY UPTOWN SCHOOL COMPLEX 37 NO NJASK4 ATLANTIC ATLANTIC CITY NEW JERSEY AVE 41 YES NJASK4 ATLANTIC ATLANTIC CITY RICHMOND AVE 41 YES NJASK4 ATLANTIC ATLANTIC CITY DR M L KING JR SCH COMP 38 NO NJASK4 ATLANTIC ATLANTIC CITY OCEANSIDE CS 37 NO NJASK4 ATLANTIC ATLANTIC CITY LEARNING CENTER CS 41 YES NJASK4 ATLANTIC BRIGANTINE CITY BRIGANTINE ELEM SCHOOL 41 YES NJASK4 ATLANTIC BUENA REGIONAL COLLINGS LAKE ELEM SCH 41 YES NJASK4 ATLANTIC BUENA REGIONAL EDGARTON MEMORIAL ELEM SC 41 YES NJASK4 ATLANTIC BUENA REGIONAL JOHN C. MILANESI ELEM SCH 41 YES NJASK4 ATLANTIC EGG HARBOR CITY CHARLES L. SPRAGG E S 39 NO NJASK4 ATLANTIC EGG HARBOR TWP EGG HARBOR TWP INTER. 33 NO NJASK4 ATLANTIC ESTELL MANOR CITY ESTELL MANOR ELEM SCH 41 YES NJASK4 ATLANTIC FOLSOM BORO FOLSOM 41 YES NJASK4 ATLANTIC GALLOWAY TWP ARTHUR RANN ELEM SCHOOL 41 YES NJASK4 ATLANTIC GALLOWAY TWP COLOGNE ELEM SCH 41 YES NJASK4 ATLANTIC GALLOWAY TWP REEDS ROAD ELEM SCH 39 NO NJASK4 ATLANTIC GALLOWAY TWP ROLAND ROGERS ELEM SCH 41 YES NJASK4 ATLANTIC GALLOWAY TWP SMITHVILLE ELEM SCHOOL 41 YES NJASK4 ATLANTIC GALLOWAY TWP SOUTH EGG HARBOR E S 41 YES NJASK4 ATLANTIC GALLOWAY TWP. GALLOWAY COMMUNITY CS 41 YES NJASK4 ATLANTIC -

New Documents on Mongolia and the Cold War

Cold War International History Project Bulletin, Issue 16 New Documents on Mongolia and the Cold War Translation and Introduction by Sergey Radchenko1 n a freezing November afternoon in Ulaanbaatar China and Russia fell under the Mongolian sword. However, (Ulan Bator), I climbed the Zaisan hill on the south- after being conquered in the 17th century by the Manchus, Oern end of town to survey the bleak landscape below. the land of the Mongols was divided into two parts—called Black smoke from gers—Mongolian felt houses—blanketed “Outer” and “Inner” Mongolia—and reduced to provincial sta- the valley; very little could be discerned beyond the frozen tus. The inhabitants of Outer Mongolia enjoyed much greater Tuul River. Chilling wind reminded me of the cold, harsh autonomy than their compatriots across the border, and after winter ahead. I thought I should have stayed at home after all the collapse of the Qing dynasty, Outer Mongolia asserted its because my pen froze solid, and I could not scribble a thing right to nationhood. Weak and disorganized, the Mongolian on the documents I carried up with me. These were records religious leadership appealed for help from foreign countries, of Mongolia’s perilous moves on the chessboard of giants: including the United States. But the first foreign troops to its strategy of survival between China and the Soviet Union, appear were Russian soldiers under the command of the noto- and its still poorly understood role in Asia’s Cold War. These riously cruel Baron Ungern who rode past the Zaisan hill in the documents were collected from archival depositories and pri- winter of 1921. -

GENERAL PHOTOGRAPHS File Subject Index

GENERAL PHOTOGRAPHS File Subject Index A (General) Abeokuta: the Alake of Abram, Morris B.: see A (General) Abruzzi: Duke of Absher, Franklin Roosevelt: see A (General) Adams, C.E.: see A (General) Adams, Charles, Dr. D.F., C.E., Laura Franklin Delano, Gladys, Dorothy Adams, Fred: see A (General) Adams, Frederick B. and Mrs. (Eilen W. Delano) Adams, Frederick B., Jr. Adams, William Adult Education Program Advertisements, Sears: see A (General) Advertising: Exhibits re: bill (1944) against false advertising Advertising: Seagram Distilleries Corporation Agresta, Fred Jr.: see A (General) Agriculture Agriculture: Cotton Production: Mexican Cotton Pickers Agriculture: Department of (photos by) Agriculture: Department of: Weather Bureau Agriculture: Dutchess County Agriculture: Farm Training Program Agriculture: Guayule Cultivation Agriculture: Holmes Foundry Company- Farm Plan, 1933 Agriculture: Land Sale Agriculture: Pig Slaughter Agriculture: Soil Conservation Agriculture: Surplus Commodities (Consumers' Guide) Aircraft (2) Aircraft, 1907- 1914 (2) Aircraft: Presidential Aircraft: World War II: see World War II: Aircraft Airmail Akihito, Crown Prince of Japan: Visit to Hyde Park, NY Akin, David Akiyama, Kunia: see A (General) Alabama Alaska Alaska, Matanuska Valley Albemarle Island Albert, Medora: see A (General) Albright, Catherine Isabelle: see A (General) Albright, Edward (Minister to Finland) Albright, Ethel Marie: see A (General) Albright, Joe Emma: see A (General) Alcantara, Heitormelo: see A (General) Alderson, Wrae: see A (General) Aldine, Charles: see A (General) Aldrich, Richard and Mrs. Margaret Chanler Alexander (son of Charles and Belva Alexander): see A (General) Alexander, John H. Alexitch, Vladimir Joseph Alford, Bradford: see A (General) Allen, Mrs. Idella: see A (General) 2 Allen, Mrs. Mary E.: see A (General) Allen, R.C. -

TRACING the DISCOURSE of AMERICAN EXCEPTIONALISM by Aron Tabor

DOES EXCEPTION PROVE THE RULE? TRACING THE DISCOURSE OF AMERICAN EXCEPTIONALISM By Aron Tabor Submitted to Central European University Doctoral School of Political Science, Public Policy and International Relations In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Political Science Supervisor: Alexander Astrov Word Count: 91,719 Budapest, Hungary 2019 ii Declaration I hereby declare that no parts of this thesis have been accepted for any other degrees in any other institutions. This thesis contains no material previously written and/or published by another person, except where appropriate acknowledgement is made in the form of bibliographical reference. Aron Tabor April 26, 2019 iii iv Abstract The first two decades of the twenty-first century saw an unprecedented proliferation of the discourse of American exceptionalism both in scholarly works and in the world of politics; several recent contributions have characterized this notion in the context of a set of beliefs that create, construct, (re-)define and reproduce a particular foreign policy identity. At the same time, some authors also note that the term “American exceptionalism” itself was born in a specific discourse within U.S. Communism, and, for a period, it was primarily understood with reference to the peculiar causes behind the absence of a strong socialist movement in the United States. The connection between this original meaning and the later usage is not fully explored; often it is assumed that “exceptionalism” existed before the label was created as the idea is traced back to the founding of the American nation or even to the colonial period. -

The Bolshevil{S and the Chinese Revolution 1919-1927 Chinese Worlds

The Bolshevil{s and the Chinese Revolution 1919-1927 Chinese Worlds Chinese Worlds publishes high-quality scholarship, research monographs, and source collections on Chinese history and society from 1900 into the next century. "Worlds" signals the ethnic, cultural, and political multiformity and regional diversity of China, the cycles of unity and division through which China's modern history has passed, and recent research trends toward regional studies and local issues. It also signals that Chineseness is not contained within territorial borders overseas Chinese communities in all countries and regions are also "Chinese worlds". The editors see them as part of a political, economic, social, and cultural continuum that spans the Chinese mainland, Taiwan, Hong Kong, Macau, South East Asia, and the world. The focus of Chinese Worlds is on modern politics and society and history. It includes both history in its broader sweep and specialist monographs on Chinese politics, anthropology, political economy, sociology, education, and the social science aspects of culture and religions. The Literary Field of New Fourth Artny Twentieth-Century China Communist Resistance along the Edited by Michel Hockx Yangtze and the Huai, 1938-1941 Gregor Benton Chinese Business in Malaysia Accumulation, Ascendance, A Road is Made Accommodation Communism in Shanghai 1920-1927 Edmund Terence Gomez Steve Smith Internal and International Migration The Bolsheviks and the Chinese Chinese Perspectives Revolution 1919-1927 Edited by Frank N Pieke and Hein Mallee