New Exception for Parody

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Significance of Anime As a Novel Animation Form, Referencing Selected Works by Hayao Miyazaki, Satoshi Kon and Mamoru Oshii

The significance of anime as a novel animation form, referencing selected works by Hayao Miyazaki, Satoshi Kon and Mamoru Oshii Ywain Tomos submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Aberystwyth University Department of Theatre, Film and Television Studies, September 2013 DECLARATION This work has not previously been accepted in substance for any degree and is not being concurrently submitted in candidature for any degree. Signed………………………………………………………(candidate) Date …………………………………………………. STATEMENT 1 This dissertation is the result of my own independent work/investigation, except where otherwise stated. Other sources are acknowledged explicit references. A bibliography is appended. Signed………………………………………………………(candidate) Date …………………………………………………. STATEMENT 2 I hereby give consent for my dissertation, if accepted, to be available for photocopying and for inter-library loan, and for the title and summary to be made available to outside organisations. Signed………………………………………………………(candidate) Date …………………………………………………. 2 Acknowledgements I would to take this opportunity to sincerely thank my supervisors, Elin Haf Gruffydd Jones and Dr Dafydd Sills-Jones for all their help and support during this research study. Thanks are also due to my colleagues in the Department of Theatre, Film and Television Studies, Aberystwyth University for their friendship during my time at Aberystwyth. I would also like to thank Prof Josephine Berndt and Dr Sheuo Gan, Kyoto Seiko University, Kyoto for their valuable insights during my visit in 2011. In addition, I would like to express my thanks to the Coleg Cenedlaethol for the scholarship and the opportunity to develop research skills in the Welsh language. Finally I would like to thank my wife Tomoko for her support, patience and tolerance over the last four years – diolch o’r galon Tomoko, ありがとう 智子. -

Mimesis: Foot Washing from Luke to John

Ephemerides Theologicae Lovanienses 92/4 (2016) 655-670. doi: 10.2143/ETL.92.4.3183465 © 2016 by Ephemerides Theologicae Lovanienses. All rights reserved. Mimesis: Foot Washing from Luke to John Keith L. YODER University of Massachusetts at Amherst Introduction In this paper I argue that the Foot Washing of John 13,1-17, as literary composition, is a mimesis of the Sinful Woman narrative of Luke 7,36-501. Maurits Sabbe first proposed this mimetic association in 19822, followed by Thomas Brodie in 19933 and Ingrid Rosa Kitzberger in 19944, but the pro- posal dropped from view without ever being fully explored. Now a fresh comparison of the two texts uncovers a large array of previously unsurveyed parallels. Evaluation of old and new evidence will demonstrate that this is an instance of creative imitation, that combination of literary μίμησις (imi- tatio) and ζήλωσις (aemulatio) widely practiced by writers in antiquity5. Key directional indicators will point to Luke as the original and John as the emulation. I will here examine fifteen features in Luke that are paralleled in John. Throughout, I reference the internal tests for intertextual mimesis developed by Dennis R. MacDonald: the density, order, distinctiveness, and interpret- ability of the parallels6. Since external evidence pertinent to the relative dating of the Gospels of Luke and John is scarce and subject to debate, I will not address his tests of accessibility and analogy, but will focus instead on pointers of directionality arising from the internal evidence. 1. This paper was first presented at the March 2016 Annual Meeting of the Eastern Great Lakes Region of the Society of Biblical Literature, in Perrysville, Ohio, USA. -

Thoughts on Diegetic Music in the Early Operas of Zandonai1

DAVID ROSEN THOUGHTS ON DIEGETIC MUSIC IN THE EARLY OPERAS OF ZANDONAI1 Diegetic music – «music that (apparently) issues from a source within the narrative» (Gorbman, 23)2 – plays an important role in Zandonai’s early operas: not only does it appear frequently, but it often pushes the action forward, eliciting responses from the characters who hear it. And some of its uses are unusual, if not unprecedented. In this essay I focus on Il grillo del focolare but make cross-references to diegetic music in L’uccellino d’oro, Conchita, and Melenis as well. Readers unfamiliar with these operas may want to consult plot summaries, for example, in Dryden (469-79). Table 1 lists the passages referred to in this essay. 1 I want to express my thanks to the Centro internazionale di studi «Riccardo Zan- donai», especially to Diego Cescotti, Irene Comisso, and Federica Fortunato for assistance of all sorts before, during, and after the conference. Thanks go also to Gary Moulsdale for his comments on an earlier version of this text, to Ann Beck- man and other friends on WM-L (my favorite online opera discussion group) for answering some questions about precedents for certain uses of diegetic music, and to Carol Rosen for having translated into Italian the version of this essay that I delivered at the conference. 2 Citations refer to the Selective Bibliography at the end of this essay. The category ‘diegetic music’ thus includes both ‘musica in scena’ and ‘musica di scena’ (for the distinction see, for example, Girardi, 101-102). That is, it may include music emanating from offstage (whether in the wings or from the orchestra pit) or on- stage in full view of the audience. -

Double-Edged Imitation

Double-Edged Imitation Theories and Practices of Pastiche in Literature Sanna Nyqvist University of Helsinki 2010 © Sanna Nyqvist 2010 ISBN 978-952-92-6970-9 Nord Print Oy Helsinki 2010 Acknowledgements Among the great pleasures of bringing a project like this to com- pletion is the opportunity to declare my gratitude to the many people who have made it possible and, moreover, enjoyable and instructive. My supervisor, Professor H.K. Riikonen has accorded me generous academic freedom, as well as unfailing support when- ever I have needed it. His belief in the merits of this book has been a source of inspiration and motivation. Professor Steven Connor and Professor Suzanne Keen were as thorough and care- ful pre-examiners as I could wish for and I am very grateful for their suggestions and advice. I have been privileged to conduct my work for four years in the Finnish Graduate School of Literary Studies under the direc- torship of Professor Bo Pettersson. He and the Graduate School’s Post-Doctoral Researcher Harri Veivo not only offered insightful and careful comments on my papers, but equally importantly cre- ated a friendly and encouraging atmosphere in the Graduate School seminars. I thank my fellow post-graduate students – Dr. Juuso Aarnio, Dr. Ulrika Gustafsson, Dr. Mari Hatavara, Dr. Saija Isomaa, Mikko Kallionsivu, Toni Lahtinen, Hanna Meretoja, Dr. Outi Oja, Dr. Merja Polvinen, Dr. Riikka Rossi, Dr. Hanna Ruutu, Juho-Antti Tuhkanen and Jussi Willman – for their feed- back and collegial support. The rush to meet the seminar deadline was always amply compensated by the discussions in the seminar itself, and afterwards over a glass of wine. -

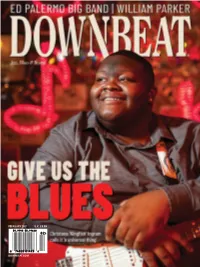

Downbeat.Com February 2021 U.K. £6.99

FEBRUARY 2021 U.K. £6.99 DOWNBEAT.COM FEBRUARY 2021 DOWNBEAT 1 FEBRUARY 2021 VOLUME 88 / NUMBER 2 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Reviews Editor Dave Cantor Contributing Editor Ed Enright Creative Director ŽanetaÎuntová Design Assistant Will Dutton Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Oakes ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile Vice President of Sales 630-359-9345 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney Vice President of Sales 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Grace Blackford 630-359-9358 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank-John Hadley; Chicago: Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Jeff Johnson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Sean J. O’Connell, Chris Walker, Josef Woodard, Scott Yanow; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Andrea Canter; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, Jennifer Odell; New York: Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Philip Freeman, Stephanie Jones, Matthew Kassel, Jimmy Katz, Suzanne Lorge, Phillip Lutz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Bill Milkowski, Allen Morrison, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Tom Staudter, Jack Vartoogian; Philadelphia: Shaun Brady; Portland: Robert Ham; San Francisco: Yoshi Kato, Denise Sullivan; Seattle: Paul de Barros; Washington, D.C.: Willard Jenkins, John Murph, Michael Wilderman; Canada: J.D. Considine, James Hale; France: Jean Szlamowicz; Germany: Hyou Vielz; Great Britain: Andrew Jones; Portugal: José Duarte; Romania: Virgil Mihaiu; Russia: Cyril Moshkow. -

Understanding Music Past and Present

Understanding Music Past and Present N. Alan Clark, PhD Thomas Heflin, DMA Jeffrey Kluball, EdD Elizabeth Kramer, PhD Understanding Music Past and Present N. Alan Clark, PhD Thomas Heflin, DMA Jeffrey Kluball, EdD Elizabeth Kramer, PhD Dahlonega, GA Understanding Music: Past and Present is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribu- tion-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. This license allows you to remix, tweak, and build upon this work, even commercially, as long as you credit this original source for the creation and license the new creation under identical terms. If you reuse this content elsewhere, in order to comply with the attribution requirements of the license please attribute the original source to the University System of Georgia. NOTE: The above copyright license which University System of Georgia uses for their original content does not extend to or include content which was accessed and incorpo- rated, and which is licensed under various other CC Licenses, such as ND licenses. Nor does it extend to or include any Special Permissions which were granted to us by the rightsholders for our use of their content. Image Disclaimer: All images and figures in this book are believed to be (after a rea- sonable investigation) either public domain or carry a compatible Creative Commons license. If you are the copyright owner of images in this book and you have not authorized the use of your work under these terms, please contact the University of North Georgia Press at [email protected] to have the content removed. ISBN: 978-1-940771-33-5 Produced by: University System of Georgia Published by: University of North Georgia Press Dahlonega, Georgia Cover Design and Layout Design: Corey Parson For more information, please visit http://ung.edu/university-press Or email [email protected] TABLE OF C ONTENTS MUSIC FUNDAMENTALS 1 N. -

Narrative Theory

NARRATIVE THEORY EDITED BY JAMES PHELAN AND PETER J. RABINOWITZ A Companion to Narrative Theory Blackwell Companions to Literature and Culture This series offers comprehensive, newly written surveys of key periods and movements and certain major authors, in English literary culture and history. Extensive volumes provide new perspectives and positions on contexts and on canonical and postcanoni- cal texts, orientating the beginning student in new fields of study and providing the experienced undergraduate and new graduate with current and new directions, as pioneered and developed by leading scholars in the field. 1 A Companion to Romanticism Edited by Duncan Wu 2 A Companion to Victorian Literature and Culture Edited by Herbert F. Tucker 3 A Companion to Shakespeare Edited by David Scott Kastan 4 A Companion to the Gothic Edited by David Punter 5 A Feminist Companion to Shakespeare Edited by Dympna Callaghan 6 A Companion to Chaucer Edited by Peter Brown 7 A Companion to Literature from Milton to Blake Edited by David Womersley 8 A Companion to English Renaissance Literature and Culture Edited by Michael Hattaway 9 A Companion to Milton Edited by Thomas N. Corns 10 A Companion to Twentieth-Century Poetry Edited by Neil Roberts 11 A Companion to Anglo-Saxon Literature and Culture Edited by Phillip Pulsiano and Elaine Treharne 12 A Companion to Restoration Drama Edited by Susan J. Owen 13 A Companion to Early Modern Women’s Writing Edited by Anita Pacheco 14 A Companion to Renaissance Drama Edited by Arthur F. Kinney 15 A Companion to Victorian Poetry Edited by Richard Cronin, Alison Chapman, and Antony H. -

Instrumental Rationality: a Reprise by Joseph Raz1 HE OPPORTUNITY

JOURNAL OF ETHICS & SOCIAL PHILOSOPHY | SYMPOSIUM INSTRUMENTAL RATIONALITY: A REPRISE Joseph Raz Instrumental Rationality: A Reprise By Joseph Raz1 HE OPPORTUNITY TO REPLY to four challenging comments enables me not only to remove some misunderstandings, but also to Tdevelop some ideas regarding which “The Myth of Instrumental Ra- tionality” (“The Myth,” as I shall refer to it) was silent or even misleading. First let me set out the main theses of The Myth. Assuming, as I do, that facts about the value of kinds of action constitute reasons for or against them, and that “rationality” or “irrationality” (or de- grees of either) refer either to the capacity to appreciate and respond appro- priately to reasons, or (in other contexts) to the way it is exercised, I argued that:2 1) There are instrumental or as, for reasons given, I call them “facilita- tive” reasons: When we have an undefeated reason to take an action we have reason to perform any one (but only one) of the possible (for us) alternative plans which facilitate it.3 2) The rationality or lack of it displayed in our reactions to our own ends – in particular adopting what we believe are means to their realization, or our failure to adopt such means – consists in the exercise or failure to exercise properly the same capacity, and in conforming with or violating the same principles of rationality, which we exercise or fail to exercise, conform to or fail to conform to in other contexts. The supposition that there is a special type of rationality, or of rational principles, to which “instrumental rational- ity” refers is the myth of the title of my article. -

Answering the Real Question About Fictive Emotions by Kyle Furlane

A Thesis entitled Beyond the Paradox: Answering the Real Question about Fictive Emotions by Kyle Furlane Submitted to the Graduate Faculty as partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts Degree in Philosophy _________________________________________ Dr. Charles Blatz, Committee Chair _________________________________________ Dr. John Sarnecki, Committee Member _________________________________________ Dr. Ammon Allred, Committee Member _________________________________________ Dr. Patricia R. Komuniecki, Dean College of Graduate Studies The University of Toledo May 2012 Copyright 2012, Kyle Furlane This document is copyrighted material. Under copyright law, no parts of this document may be reproduced without the expressed permission of the author. An Abstract of Beyond the Paradox: Answering the Real Question about Fictive Emotions by Kyle Furlane Submitted to the Graduate Faculty as partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Master of Arts Degree in Philosophy The University of Toledo May 2012 Across cultures, people have engagements with fictions which can result in physiological and psychological responses. These responses are what I call fictive emotions. Fictive emotions, though phenomenologically similar to other types of emotions, are distinct in that they seem to be a reaction to characters and events that do not exist. This observation has lead philosophers to ask three questions about fictive emotions: the conceptual (Are fictive emotions possible?), the normative (Are fictive emotions rational?), and the causal(How is it that fictions can cause fictive emotions?). In the past, philosophers have focused almost exclusively on the conceptual and normative questions, avoiding the more important causal question. In the following I explain why a focus on the conceptual and normative questions is misguided and the superior benefits of working toward an answer to the causal question. -

Translation Events in Cross-Language Informationretrieval

Syracuse University SURFACE Te School of Information Studies Faculty School of Information Studies (iSchool) Scholarship 2003 Translation Events in Cross-Language Information Retrieval: Lexical Ambiguity, Lexical Holes, Vocabulary Mismatch, and Correct Translations Anne Roel Diekema Syracuse University Follow this and additional works at: htp: surface.syr.edu istpub Part of the Library and Information Science Commons Recommended Citation Translation Events in Cross-Language Information Retrieval: Lexical Ambiguity, Lexical Holes, Vocabulary Mismatch, and Correct Translations (2003) Tis Article is brought to you for free and open access by the School of Information Studies (iSchool) at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in Te School of Information Studies Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. TRANSLATION EVENTS IN CROSS-LANGUAGE INFORMATION RETRIEVAL: LEXICAL AMBIGUITY, LEXICAL HOLES, VOCABULARY MISMATCH, AND CORRECT TRANSLATIONS by ANNE R. DIEKEMA Bac., Haagse Hogeschool, 1993 M.L.S., Syracuse University, 1995 DISSERTATION School of Information Studies, Syracuse University May 2003 Anne Diekema: Dissertation (May 22, 2003) iii Copyright 2003 Anne Roel Diekema All rights reserved Anne Diekema: Dissertation (May 22, 2003) iv ABSTRACT Cross-Language Information Retrieval (CLIR) systems enable users to formulate queries in their native language to retrieve documents in foreign languages. Because queries and documents in CLIR do not necessarily share the same language, translation is needed before matching can take place. This translation step tends to cause a reduction in the retrieval performance of CLIR as compared to monolingual information retrieval. The prevailing CLIR approach and the focus of this study is query translation. -

From the Con Chair

Bakuretsu Con 2018 Thank you for attending Bakuretsu Con. We hope that you will have fun this weekend. Check out our information desk for up-to-date schedules and other information. Enjoy the Con! BAKURETSU CON CODE OF CONDUCT Your membership to the convention is a privilege. Your badge is your proof of membership; never forget that you are representing Bakuretsu Con once you purchase a badge. Please be respectful to your fellow convention attendees, the convention staff, and the hotel. We reserve the right to revoke the membership privileges of any attendee for any reason. If we find your conduct inappropriate and feel you deserve a warning, one will be given. If you are given a warning, a hole will be punched in your badge. Only one warning will be given; any problems after that and you will be asked to leave. If you are asked to leave the convention your badge fee will NOT be refunded. OTHER THINGS TO REMEMBER - If it’s illegal outside of the convention, it’s still illegal here. - If you are found to be in possession of anything illegal you will be evicted from the convention and the police may be called. - There is no smoking in the convention center. Please do not smoke in doorways either. - No alcohol is permitted in any of the convention areas. - No weapons allowed. If you buy a weapon from a dealer, please bring it to your room or car. - We are not responsible for lost or stolen articles. Please don’t leave your belongings unattended. Lost and found items will be brought to the info desk, or, after the Con, the hotel front desk. -

On the Threshold of Poems: a Paratextual Approach to the Narrative/Lyric Opposition in Italian Renaissance Poetry

This is a repository copy of On the Threshold of Poems: a Paratextual Approach to the Narrative/Lyric Opposition in Italian Renaissance Poetry. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/119858/ Version: Accepted Version Book Section: Pich, F (2019) On the Threshold of Poems: a Paratextual Approach to the Narrative/Lyric Opposition in Italian Renaissance Poetry. In: Venturi, F, (ed.) Self-Commentary in Early Modern European Literature, 1400-1700. Intersections, 62 . Brill , pp. 99-134. ISBN 9789004346864 https://doi.org/10.1163/9789004396593_006 © Koninklijke Brill NV, Leiden, 2019. This is an author produced version of a paper published in Self-Commentary in Early Modern European Literature, 1400-1700 (Intersections). Uploaded in accordance with the publisher's self-archiving policy. Reuse Items deposited in White Rose Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the White Rose Research Online record for the item. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ 1 On the Threshold of Poems: a Paratextual Approach to the Narrative/Lyric Opposition in Italian Renaissance Poetry Federica Pich Summary This contribution focuses on the presence and function of prose rubrics in fifteenth- and sixteenth-century lyric collections.