UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA, SAN DIEGO Sondheim

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tom Fleischman CAS

Career Achievement Award Recipient Tom Fleischman CAS CAS Award Nominees Production Equipment FOMO How the CAS Started Remembering Jim Alexander WINTER 2020 CINEMA AUDIO SOCIETY AWARDS NOMINEE OUTSTANDING ACHIEVEMENT IN SOUND MIXING MPSE GOLDEN REEL AWARDS NOMINEE FEATURE - ADR/DIALOGUE PHILIP STOCKTON, MPSE, EUGENE GEARTY, MARISSA LITTLEFIELD “EXQUISITELY MADE, EVERY DETAIL CAREFULLY CONSIDERED. IT FEELS UTTERLY TRANSPORTING.” NETFLIXGUILDS.COM CAS QUARTERLY, COVER 2 NETFLIX: THE IRISHMAN PUB DATE 12/30/19 BLEED: 8.625” X 11.125” TRIM: 8.375” X 10.875” CINEMA AUDIO SOCIETY AWARDS NOMINEE OUTSTANDING ACHIEVEMENT IN SOUND MIXING MPSE GOLDEN REEL AWARDS NOMINEE FEATURES FEATURE - ADR/DIALOGUE Production Sound Equipment Purchases . 20 PHILIP STOCKTON, MPSE, EUGENE GEARTY, MARISSA LITTLEFIELD Ever have a “Fear of Missing Out”? 147th AES Convention . 26 Career Achievement Recipient . 34 Re-recording mixer Tom Fleischman CAS CAS Filmmaker Award . 44 34 Director, producer, and writer James Mangold CAS Award Nominations . 46 Outstanding Product Nominees . 50 Student Recognition Award Finalists . 52 The Start of the CAS . 54 Bob Hoyt had a vision A Case Study in Multilanguage Production Sound . 60 Possession 54 The “Sound” of Genre Storytelling . 64 Mixing approaches infl uenced by genre Remembering a Legend . 68 Production sound mixer Jim Alexander “EXQUISITELY MADE, DEPARTMENTS EVERY DETAIL The President’s Letter . 4 From the Editor . 6 CAREFULLY CONSIDERED. 60 Collaborators . 9 Meet the people behind the words IT FEELS UTTERLY Technically Speaking -

February 7, 2021

VILLANOVA THEATRE PRESENTS STREAMING JANUARY 28 - FEBRUARY 7, 2021 About Villanova University Since 1842, Villanova University’s Augustinian Catholic intellectual tradition has been the cornerstone of an academic community in which students learn to think critically, act compassionately and succeed while serving others. There are more than 10,000 undergraduate, graduate and law students in the University’s six colleges – the College of Liberal Arts and Sciences, the Villanova School of Business, the College of Engineering, the M. Louise Fitzpatrick College of Nursing, the College of Professional Studies and the Villanova University School of Law. As students grow intellectually, Villanova prepares them to become ethical leaders who create positive change everywhere life takes them. In Gratitude The faculty, staff and students of Villanova Theatre extend sincere gratitude to those generous benefactors who have established endowed funds in support of our efforts: Marianne M. and Charles P. Connolly Jr. ’70 Dorothy Ann and Bernard A. Coyne, Ph.D. ̓55 Patricia M. ’78 and Joseph C. Franzetti ’78 The Donald R. Kurz Family Peter J. Lavezzoli ’60 Patricia A. Maskinas Msgr. Joseph F. X. McCahon ’65 Mary Anne C. Morgan ̓70 and Family & Friends of Brian G. Morgan ̓67, ̓70 Anthony T. Ponturo ’74 Eric J. Schaeffer and Susan Trimble Schaeffer ’78 The Thomas and Tracey Gravina Foundation For information about how you can support the Theatre Department, please contact Heather Potts-Brown, Director of Annual Giving, at (610) 519-4583. gratefully acknowledges the generous support of our many patrons & subscribers. We wish to offer special thanks to our donors. 20-21 Benefactors A Running Friend William R. -

The Significance of Anime As a Novel Animation Form, Referencing Selected Works by Hayao Miyazaki, Satoshi Kon and Mamoru Oshii

The significance of anime as a novel animation form, referencing selected works by Hayao Miyazaki, Satoshi Kon and Mamoru Oshii Ywain Tomos submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Aberystwyth University Department of Theatre, Film and Television Studies, September 2013 DECLARATION This work has not previously been accepted in substance for any degree and is not being concurrently submitted in candidature for any degree. Signed………………………………………………………(candidate) Date …………………………………………………. STATEMENT 1 This dissertation is the result of my own independent work/investigation, except where otherwise stated. Other sources are acknowledged explicit references. A bibliography is appended. Signed………………………………………………………(candidate) Date …………………………………………………. STATEMENT 2 I hereby give consent for my dissertation, if accepted, to be available for photocopying and for inter-library loan, and for the title and summary to be made available to outside organisations. Signed………………………………………………………(candidate) Date …………………………………………………. 2 Acknowledgements I would to take this opportunity to sincerely thank my supervisors, Elin Haf Gruffydd Jones and Dr Dafydd Sills-Jones for all their help and support during this research study. Thanks are also due to my colleagues in the Department of Theatre, Film and Television Studies, Aberystwyth University for their friendship during my time at Aberystwyth. I would also like to thank Prof Josephine Berndt and Dr Sheuo Gan, Kyoto Seiko University, Kyoto for their valuable insights during my visit in 2011. In addition, I would like to express my thanks to the Coleg Cenedlaethol for the scholarship and the opportunity to develop research skills in the Welsh language. Finally I would like to thank my wife Tomoko for her support, patience and tolerance over the last four years – diolch o’r galon Tomoko, ありがとう 智子. -

KS5 Exploring Performance Styles in Musical Theatre

Exploring performance KS5 styles in Musical Theatre Heidi McEntee Heidi McEntee is a Dance and KS5 – BTEC LEVEL 3, UNIT D10 Performing Arts specialist based in the Midlands. She has worked in education for over fifteen years delivering a variety of Dance and Performing Arts qualifications at Introduction Levels 1, 2 and 3. She is a Senior Unit D10: Exploring Performance Styles is one of the three units which sit within Module D: Assessment Associate working on musical theatre Skills Development from the new BTEC Level 3 in Performing Arts Practice Performing Arts qualifications and (musical theatre) qualification. This scheme of work focuses on the first unit which introduces a contributing author for student and explores different musical theatre styles. revision guides. This unit requires learners to develop their practical skills in dance, acting and singing while furthering their understanding of musical theatre styles. The unit culminates in a performance of two extracts in two different styles of musical theatre as well as a critical review of the stylistic qualities within these extracts. This scheme of work provides a suggested approach to six weeks of introductory classes, as a part of a full timetable, which explores the development of performance styles through the history of musical theatre via practical activities, short projects and research tasks. Learning objectives By the end of this scheme, learners will have: § Investigated the history of musical theatre and the factors which have influenced its development Unit D10: Exploring Performance § Explored the characteristics of different musical theatre styles and how they have developed Styles from BTEC L3 Nationals over time Performing Arts Practice (musical § Applied stylistic conventions to the performance of material theatre) (2019) § Examined professional work through critical analysis. -

Colonial Concert Series Featuring Broadway Favorites

Amy Moorby Press Manager (413) 448-8084 x15 [email protected] Becky Brighenti Director of Marketing & Public Relations (413) 448-8084 x11 [email protected] For Immediate Release, Please: Berkshire Theatre Group Presents Colonial Concert Series: Featuring Broadway Favorites Kelli O’Hara In-Person in the Berkshires Tony Award-Winner for The King and I Norm Lewis: In Concert Tony Award Nominee for The Gershwins’ Porgy & Bess Carolee Carmello: My Outside Voice Three-Time Tony Award Nominee for Scandalous, Lestat, Parade Krysta Rodriguez: In Concert Broadway Actor and Star of Netflix’s Halston Stephanie J. Block: Returning Home Tony Award-Winner for The Cher Show Kate Baldwin & Graham Rowat: Dressed Up Again Two-Time Tony Award Nominee for Finian’s Rainbow, Hello, Dolly! & Broadway and Television Actor An Evening With Rachel Bay Jones Tony, Grammy and Emmy Award-Winner for Dear Evan Hansen Click Here To Download Press Photos Pittsfield, MA - The Colonial Concert Series: Featuring Broadway Favorites will captivate audiences throughout the summer with evenings of unforgettable performances by a blockbuster lineup of Broadway talent. Concerts by Tony Award-winner Kelli O’Hara; Tony Award nominee Norm Lewis; three-time Tony Award nominee Carolee Carmello; stage and screen actor Krysta Rodriguez; Tony Award-winner Stephanie J. Block; two-time Tony Award nominee Kate Baldwin and Broadway and television actor Graham Rowat; and Tony Award-winner Rachel Bay Jones will be presented under The Big Tent outside at The Colonial Theatre in Pittsfield, MA. Kate Maguire says, “These intimate evenings of song will be enchanting under the Big Tent at the Colonial in Pittsfield. -

Mimesis: Foot Washing from Luke to John

Ephemerides Theologicae Lovanienses 92/4 (2016) 655-670. doi: 10.2143/ETL.92.4.3183465 © 2016 by Ephemerides Theologicae Lovanienses. All rights reserved. Mimesis: Foot Washing from Luke to John Keith L. YODER University of Massachusetts at Amherst Introduction In this paper I argue that the Foot Washing of John 13,1-17, as literary composition, is a mimesis of the Sinful Woman narrative of Luke 7,36-501. Maurits Sabbe first proposed this mimetic association in 19822, followed by Thomas Brodie in 19933 and Ingrid Rosa Kitzberger in 19944, but the pro- posal dropped from view without ever being fully explored. Now a fresh comparison of the two texts uncovers a large array of previously unsurveyed parallels. Evaluation of old and new evidence will demonstrate that this is an instance of creative imitation, that combination of literary μίμησις (imi- tatio) and ζήλωσις (aemulatio) widely practiced by writers in antiquity5. Key directional indicators will point to Luke as the original and John as the emulation. I will here examine fifteen features in Luke that are paralleled in John. Throughout, I reference the internal tests for intertextual mimesis developed by Dennis R. MacDonald: the density, order, distinctiveness, and interpret- ability of the parallels6. Since external evidence pertinent to the relative dating of the Gospels of Luke and John is scarce and subject to debate, I will not address his tests of accessibility and analogy, but will focus instead on pointers of directionality arising from the internal evidence. 1. This paper was first presented at the March 2016 Annual Meeting of the Eastern Great Lakes Region of the Society of Biblical Literature, in Perrysville, Ohio, USA. -

THE BRILL BUILDING, 1619 Broadway (Aka 1613-23 Broadway, 207-213 West 49Th Street), Manhattan Built 1930-31; Architect, Victor A

Landmarks Preservation Commission March 23, 2010, Designation List 427 LP-2387 THE BRILL BUILDING, 1619 Broadway (aka 1613-23 Broadway, 207-213 West 49th Street), Manhattan Built 1930-31; architect, Victor A. Bark, Jr. Landmark Site: Borough of Manhattan Tax Map Block 1021, Lot 19 On October 27, 2009 the Landmarks Preservation Commission held a public hearing on the proposed designation of the Brill Building and the proposed designation of the related Landmark site. The hearing had been duly advertised in accordance with provisions of law. Three people spoke in support of designation, including representatives of the owner, New York State Assembly Member Richard N. Gottfried, and the Historic Districts Council. There were no speakers in opposition to designation.1 Summary Since its construction in 1930-31, the 11-story Brill Building has been synonymous with American music – from the last days of Tin Pan Alley to the emergence of rock and roll. Occupying the northwest corner of Broadway and West 49th Street, it was commissioned by real estate developer Abraham Lefcourt who briefly planned to erect the world’s tallest structure on the site, which was leased from the Brill Brothers, owners of a men’s clothing store. When Lefcourt failed to meet the terms of their agreement, the Brills foreclosed on the property and the name of the nearly-complete structure was changed from the Alan E. Lefcourt Building to the, arguably more melodious sounding, Brill Building. Designed in the Art Deco style by architect Victor A. Bark, Jr., the white brick elevations feature handsome terra-cotta reliefs, as well as two niches that prominently display stone and brass portrait busts that most likely portray the developer’s son, Alan, who died as the building was being planned. -

Sondheim's 'Assassins' Playwrights Horizons Through Feb

THE HOLLYWOOD REPORTER, MONDAY. JANUARY 28, 1991 49 Theater review Sondheim's 'Assassins' Playwrights Horizons Through Feb. 16 ASSASSINS Director Jerry Zaks by ROBERT OSBORNE Music-lyrics Stephen Sondheim NEW YORK — Stephen Sond- Book John Weidman heim's latest musical, "Assassins," is a Set design Loren Sherman Costume design William Ivey Long raging disappointment. Offbeat, it is. Lighting Paul Gallo Controversial, it is. Daring, it is. Good, Musical director Paul Gemignani it isn't. Irresponsible, it may be. Choreography D. J. Giagni Cast: Victor Garber, Patrick Cassidy, Terrence There's every possibility this Mann, Jonathan Hadary, Greg Germano, Eddie Sondheimer will be snuffed out Korbich, Lee Wiling'. Annie Golden. Debra Monk, quickly, despite the fact there's not a Jam Alexander. Joy Franz, Lyn Greene, John Jelli- son, Marco Olson, William Parry, Michael Shul- seat to be had during its limited man tryout run at this 139-seat off- Broadway house. Except for diehard of the song that opens and closes the Sondheim fans who'll want a gander show, "Everybody's Got the Right at anything done by the composer- (to a Dream)." lyricist, there's little here that will While a troubador-narrator (ex- satisfy or attract most theatergoers. cellently done by Patrick Cassidy) The show is a 90-minute musical counters with the suggestion "Guns kalediscope focusing on nine notori- don't right the wrongs, and soon the ous figues of history who either country's back where it belongs," killed, or attempted to kill, U.S. more emphasis is given to the theory presidents from Lincoln to Reagan. -

Putting It Together

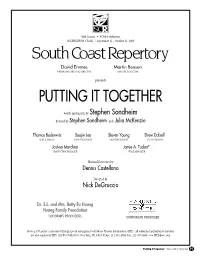

46th Season • 437th Production SEGERSTROM STAGE / September 11 - October 11, 2009 David Emmes Martin Benson Producing ArtiStic director ArtiStic director presents PUTTING IT TOGETHER words and music by Stephen Sondheim devised by Stephen Sondheim and Julia McKenzie Thomas Buderwitz Soojin Lee Steven Young Drew Dalzell Scenic deSign coStume deSign Lighting deSign Sound deSign Joshua Marchesi Jamie A. Tucker* Production mAnAger StAge mAnAger musical direction by Dennis Castellano directed by Nick DeGruccio Dr. S.L. and Mrs. Betty Eu Huang Huang Family Foundation honorAry ProducerS corPorAte Producer Putting It Together is presented through special arrangement with music theatre international (mti). All authorized performance materials are also supplied by mti. 421 West 54th Street, new york, ny 10019; Phone: 212-541-4684 Fax: 212-397-4684; www.mtiShows.com Putting It Together• SOUTH COA S T REPE R TO R Y P1 THE CAST (in order of appearance) Matt McGrath* Harry Groener* Niki Scalera* Dan Callaway* Mary Gordon Murray* MUSICIANS Dennis Castellano (conductor/keyboards), John Glaudini (synthesizer), John Reilly (woodwinds), Louis Allee (percussion) SETTING A New York penthouse apartment. Now. LENGTH Approximately two hours including one 15-minute intermission. PRODUCTION STAFF Casting ................................................................................ Joanne DeNaut, CSA Dramaturg .......................................................................... Linda Sullivan Baity Assistant Stage Manager ............................................................. -

![Florence Klotz Costume Designs [Finding Aid]. Music Division, Library](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/9291/florence-klotz-costume-designs-finding-aid-music-division-library-799291.webp)

Florence Klotz Costume Designs [Finding Aid]. Music Division, Library

Florence Klotz Costume Designs Guides to Special Collections in the Music Division of the Library of Congress Music Division, Library of Congress Washington, D.C. 2018 Contact information: http://hdl.loc.gov/loc.music/perform.contact Catalog Record: https://lccn.loc.gov/2015667105 Additional search options available at: https://hdl.loc.gov/loc.music/eadmus.mu018005 Processed by the Music Division of the Library of Congress Finding aid encoded by Library of Congress Music Division, 2018 Revised 2018 April Collection Summary Title: Florence Klotz Costume Designs Span Dates: 1971-1985 Call No.: ML31.K606 Creator: Klotz, Florence Extent: 670 items Extent: 19 containers Extent: 11.5 linear feet Language: Collection material in English Location: Music Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. LC Catalog record: https://lccn.loc.gov/2015667105 Summary: Florence Klotz was an American costume designer best known for her work on Broadway musical collaborations with composer Stephen Sondheim and director Harold (Hal) Prince, including Follies (1971), A Little Night Music (1973), and Pacific Overtures (1976). The collection contains finished costume designs, sketches, fabric samples, and other materials for five musicals and one film adaptation. Selected Search Terms The following terms have been used to index the description of this collection in the LC Catalog. They are grouped by name of person or organization, by subject or location, and by occupation and listed alphabetically. People Coleman, Cy. On the Twentieth Century. Grossman, Larry. Grind. Klotz, Florence. Sondheim, Stephen. Follies. Sondheim, Stephen. Little night music. Sondheim, Stephen. Pacific overtures. Subjects Costume design. Costume designers. Musical theater--United States. Theater--United States. -

MACBETH Classic Stage Company JOHN DOYLE, Artistic Director TONI MARIE DAVIS, Chief Operating Officer/GM Presents MACBETH by WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE

MACBETH Classic Stage Company JOHN DOYLE, Artistic Director TONI MARIE DAVIS, Chief Operating Officer/GM presents MACBETH BY WILLIAM SHAKESPEARE WITH BARZIN AKHAVAN, RAFFI BARSOUMIAN, NADIA BOWERS, N’JAMEH CAMARA, ERIK LOCHTEFELD, MARY BETH PEIL, COREY STOLL, BARBARA WALSH, ANTONIO MICHAEL WOODARD COSTUME DESIGN LIGHTING DESIGN SOUND DESIGN ANN HOULD-WARD SOLOMON WEISBARD MATT STINE FIGHT DIRECTOR PROPS SUPERVISOR THOMAS SCHALL ALEXANDER WYLIE ASSOCIATE ASSOCIATE ASSOCIATE SCENIC DESIGN COSTUME DESIGN SOUND DESIGN DAVID L. ARSENAULT AMY PRICE AJ SURASKY-YSASI PRESS PRODUCTION CASTING REPRESENTATIVES STAGE MANAGER TELSEY + COMPANY BLAKE ZIDELL AND BERNITA ROBINSON KARYN CASL, CSA ASSOCIATES ASSISTANT DESTINY LILLY STAGE MANAGER JESSICA FLEISCHMAN DIRECTED AND DESIGNED BY JOHN DOYLE MACBETH (in alphabetical order) Macduff, Captain ............................................................................ BARZIN AKHAVAN Malcolm ......................................................................................... RAFFI BARSOUMIAN Lady Macbeth ....................................................................................... NADIA BOWERS Lady Macduff, Gentlewoman ................................................... N’JAMEH CAMARA Banquo, Old Siward ......................................................................ERIK LOCHTEFELD Duncan, Old Woman .........................................................................MARY BETH PEIL Macbeth..................................................................................................... -

Education Resource Stephen Sondheim & James Lapine

Stephen Sondheim & James Lapine INTO THE WOODS Education Resource Music INTO THE WOODS - MUSIC RESOURCE INTRODUCTION From the creators of Sunday in the Park with George comes Into the Woods, a darkly enchanting story about life after the ‘happily ever after’. Stephen Sondheim and James Lapine reimagine the magical world of fairy tales as the classic stories of Jack and the Beanstalk, Cinderella, Little Red Ridinghood and Rapunzel collide with the lives of a childless baker and his wife. A brand new production of an unforgettable Tony award-winning musical. Into the Woods | Stephen Sondheim & James Lapine. 19 – 26 July 2014 | Arts Centre Melbourne, Playhouse Music and lyrics by Stephen Sondheim Book by James Lapine Originally Directed on Broadway by James Lapine By arrangement with Hal Leonard Australia Pty Ltd Exclusive agent for Music Theatre International (NY) 2 hours and 50 minutes including one interval. Victorian Opera 2014 – Into the Woods Music Resource 1 BACKGROUND Broadway Musical Music and Lyrics by Stephen Sondheim Book and Direction by James Lapine Orchestration: Jonathan Tunick Opened in San Diego on the 4th of December 1986 and premiered in Broadway on the 5th of November, 1987 Won 3 Tony Awards in 1988 Drama Desk for Best Musical Laurence Olivier Award for Best Revival Figure 1: Stephen Sondheim Performances Into the Woods has been produced several times including revivals, outdoor performances in parks, a junior version, and has been adapted for a Walt Disney film which will be released at the end of 2014. Stephen Sondheim (1930) Stephen Joshua Sondheim is one of the greatest composers and lyricists in American Theatre.