Thoughts on Diegetic Music in the Early Operas of Zandonai1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Significance of Anime As a Novel Animation Form, Referencing Selected Works by Hayao Miyazaki, Satoshi Kon and Mamoru Oshii

The significance of anime as a novel animation form, referencing selected works by Hayao Miyazaki, Satoshi Kon and Mamoru Oshii Ywain Tomos submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Aberystwyth University Department of Theatre, Film and Television Studies, September 2013 DECLARATION This work has not previously been accepted in substance for any degree and is not being concurrently submitted in candidature for any degree. Signed………………………………………………………(candidate) Date …………………………………………………. STATEMENT 1 This dissertation is the result of my own independent work/investigation, except where otherwise stated. Other sources are acknowledged explicit references. A bibliography is appended. Signed………………………………………………………(candidate) Date …………………………………………………. STATEMENT 2 I hereby give consent for my dissertation, if accepted, to be available for photocopying and for inter-library loan, and for the title and summary to be made available to outside organisations. Signed………………………………………………………(candidate) Date …………………………………………………. 2 Acknowledgements I would to take this opportunity to sincerely thank my supervisors, Elin Haf Gruffydd Jones and Dr Dafydd Sills-Jones for all their help and support during this research study. Thanks are also due to my colleagues in the Department of Theatre, Film and Television Studies, Aberystwyth University for their friendship during my time at Aberystwyth. I would also like to thank Prof Josephine Berndt and Dr Sheuo Gan, Kyoto Seiko University, Kyoto for their valuable insights during my visit in 2011. In addition, I would like to express my thanks to the Coleg Cenedlaethol for the scholarship and the opportunity to develop research skills in the Welsh language. Finally I would like to thank my wife Tomoko for her support, patience and tolerance over the last four years – diolch o’r galon Tomoko, ありがとう 智子. -

Mimesis: Foot Washing from Luke to John

Ephemerides Theologicae Lovanienses 92/4 (2016) 655-670. doi: 10.2143/ETL.92.4.3183465 © 2016 by Ephemerides Theologicae Lovanienses. All rights reserved. Mimesis: Foot Washing from Luke to John Keith L. YODER University of Massachusetts at Amherst Introduction In this paper I argue that the Foot Washing of John 13,1-17, as literary composition, is a mimesis of the Sinful Woman narrative of Luke 7,36-501. Maurits Sabbe first proposed this mimetic association in 19822, followed by Thomas Brodie in 19933 and Ingrid Rosa Kitzberger in 19944, but the pro- posal dropped from view without ever being fully explored. Now a fresh comparison of the two texts uncovers a large array of previously unsurveyed parallels. Evaluation of old and new evidence will demonstrate that this is an instance of creative imitation, that combination of literary μίμησις (imi- tatio) and ζήλωσις (aemulatio) widely practiced by writers in antiquity5. Key directional indicators will point to Luke as the original and John as the emulation. I will here examine fifteen features in Luke that are paralleled in John. Throughout, I reference the internal tests for intertextual mimesis developed by Dennis R. MacDonald: the density, order, distinctiveness, and interpret- ability of the parallels6. Since external evidence pertinent to the relative dating of the Gospels of Luke and John is scarce and subject to debate, I will not address his tests of accessibility and analogy, but will focus instead on pointers of directionality arising from the internal evidence. 1. This paper was first presented at the March 2016 Annual Meeting of the Eastern Great Lakes Region of the Society of Biblical Literature, in Perrysville, Ohio, USA. -

Double-Edged Imitation

Double-Edged Imitation Theories and Practices of Pastiche in Literature Sanna Nyqvist University of Helsinki 2010 © Sanna Nyqvist 2010 ISBN 978-952-92-6970-9 Nord Print Oy Helsinki 2010 Acknowledgements Among the great pleasures of bringing a project like this to com- pletion is the opportunity to declare my gratitude to the many people who have made it possible and, moreover, enjoyable and instructive. My supervisor, Professor H.K. Riikonen has accorded me generous academic freedom, as well as unfailing support when- ever I have needed it. His belief in the merits of this book has been a source of inspiration and motivation. Professor Steven Connor and Professor Suzanne Keen were as thorough and care- ful pre-examiners as I could wish for and I am very grateful for their suggestions and advice. I have been privileged to conduct my work for four years in the Finnish Graduate School of Literary Studies under the direc- torship of Professor Bo Pettersson. He and the Graduate School’s Post-Doctoral Researcher Harri Veivo not only offered insightful and careful comments on my papers, but equally importantly cre- ated a friendly and encouraging atmosphere in the Graduate School seminars. I thank my fellow post-graduate students – Dr. Juuso Aarnio, Dr. Ulrika Gustafsson, Dr. Mari Hatavara, Dr. Saija Isomaa, Mikko Kallionsivu, Toni Lahtinen, Hanna Meretoja, Dr. Outi Oja, Dr. Merja Polvinen, Dr. Riikka Rossi, Dr. Hanna Ruutu, Juho-Antti Tuhkanen and Jussi Willman – for their feed- back and collegial support. The rush to meet the seminar deadline was always amply compensated by the discussions in the seminar itself, and afterwards over a glass of wine. -

Cavalleria Rusticana Pagliacci

Pietro Mascagni - Ruggero Leoncavallo Cavalleria rusticana PIETRO MASCAGNI Òpera en un acte Llibret de Giovanni Targioni -Tozzetti i Guido Menasci Pagliacci RUGGERO LEONCAVALLO Òpera en dos actes Llibret i música de Ruggero Leoncavallo 5 - 22 de desembre Temporada 2019-2020 Temporada 1 Patronat de la Fundació del Gran Teatre del Liceu Comissió Executiva de la Fundació del Gran Teatre del Liceu President d’honor President Joaquim Torra Pla Salvador Alemany Mas President del patronat Vocals representants de la Generalitat de Catalunya Salvador Alemany Mas Mariàngela Vilallonga Vives, Francesc Vilaró Casalinas Vicepresidenta primera Vocals representants del Ministerio de Cultura y Deporte Mariàngela Vilallonga Vives Amaya de Miguel Toral, Antonio Garde Herce Vicepresident segon Vocals representants de l'Ajuntament de Barcelona Javier García Fernández Joan Subirats Humet, Marta Clarí Padrós Vicepresident tercer Vocal representant de la Diputació de Barcelona Joan Subirats Humet Joan Carles Garcia Cañizares Vicepresidenta quarta Vocals representants de la Societat del Gran Teatre del Liceu Núria Marín Martínez Javier Coll Olalla, Manuel Busquet Arrufat Vocals representants de la Generalitat de Catalunya Vocals representants del Consell de Mecenatge Francesc Vilaró Casalinas, Àngels Barbarà Fondevila, Àngels Jaume Giró Ribas, Luis Herrero Borque Ponsa Roca, Pilar Fernández Bozal Secretari Vocals representants del Ministerio de Cultura y Deporte Joaquim Badia Armengol Santiago Fisas Ayxelà, Amaya de Miguel Toral, Santiago de Director general -

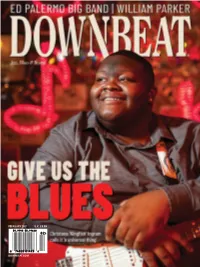

Downbeat.Com February 2021 U.K. £6.99

FEBRUARY 2021 U.K. £6.99 DOWNBEAT.COM FEBRUARY 2021 DOWNBEAT 1 FEBRUARY 2021 VOLUME 88 / NUMBER 2 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Reviews Editor Dave Cantor Contributing Editor Ed Enright Creative Director ŽanetaÎuntová Design Assistant Will Dutton Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Oakes ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile Vice President of Sales 630-359-9345 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney Vice President of Sales 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Grace Blackford 630-359-9358 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank-John Hadley; Chicago: Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Jeff Johnson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Sean J. O’Connell, Chris Walker, Josef Woodard, Scott Yanow; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Andrea Canter; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, Jennifer Odell; New York: Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Philip Freeman, Stephanie Jones, Matthew Kassel, Jimmy Katz, Suzanne Lorge, Phillip Lutz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Bill Milkowski, Allen Morrison, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Tom Staudter, Jack Vartoogian; Philadelphia: Shaun Brady; Portland: Robert Ham; San Francisco: Yoshi Kato, Denise Sullivan; Seattle: Paul de Barros; Washington, D.C.: Willard Jenkins, John Murph, Michael Wilderman; Canada: J.D. Considine, James Hale; France: Jean Szlamowicz; Germany: Hyou Vielz; Great Britain: Andrew Jones; Portugal: José Duarte; Romania: Virgil Mihaiu; Russia: Cyril Moshkow. -

Understanding Music Past and Present

Understanding Music Past and Present N. Alan Clark, PhD Thomas Heflin, DMA Jeffrey Kluball, EdD Elizabeth Kramer, PhD Understanding Music Past and Present N. Alan Clark, PhD Thomas Heflin, DMA Jeffrey Kluball, EdD Elizabeth Kramer, PhD Dahlonega, GA Understanding Music: Past and Present is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribu- tion-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. This license allows you to remix, tweak, and build upon this work, even commercially, as long as you credit this original source for the creation and license the new creation under identical terms. If you reuse this content elsewhere, in order to comply with the attribution requirements of the license please attribute the original source to the University System of Georgia. NOTE: The above copyright license which University System of Georgia uses for their original content does not extend to or include content which was accessed and incorpo- rated, and which is licensed under various other CC Licenses, such as ND licenses. Nor does it extend to or include any Special Permissions which were granted to us by the rightsholders for our use of their content. Image Disclaimer: All images and figures in this book are believed to be (after a rea- sonable investigation) either public domain or carry a compatible Creative Commons license. If you are the copyright owner of images in this book and you have not authorized the use of your work under these terms, please contact the University of North Georgia Press at [email protected] to have the content removed. ISBN: 978-1-940771-33-5 Produced by: University System of Georgia Published by: University of North Georgia Press Dahlonega, Georgia Cover Design and Layout Design: Corey Parson For more information, please visit http://ung.edu/university-press Or email [email protected] TABLE OF C ONTENTS MUSIC FUNDAMENTALS 1 N. -

Operas Performed in New York City in 2013 (Compiled by Mark Schubin)

Operas Performed in New York City in 2013 (compiled by Mark Schubin) What is not included in this list: There are three obvious categories: anything not performed in 2013, anything not within the confines of New York City, and anything not involving singing. Empire Opera was supposed to perform Montemezzi’s L'amore dei tre re in November; it was postponed to January, so it’s not on the list. Similarly, even though Bard, Caramoor, and Peak Performances provide bus service from midtown Manhattan to their operas, even though the New York City press treats the excellent but four-hours-away-by-car Glimmerglass Festival like a local company, and even though it’s faster to get from midtown Manhattan to some performances on Long Island or in New Jersey or Westchester than to, say, Queens College, those out-of-city productions are not included on the main list (just for reference, I put Bard, Caramoor, and Peak Performances in an appendix). And, although the Parterre Box New York Opera Calendar (which includes some non-opera events) listed A Rite, a music-theatrical dance piece performed at the BAM Opera House, I didn’t because no performer in it sang. I did not include anything that wasn’t a local in-person performance. The cinema transmissions from the Met, Covent Garden, La Scala, etc., are not included (nor is the movie Metallica: Through the Never, which Owen Gleiberman in Entertainment Weekly called a “grand 3-D opera”). I did not include anything that wasn’t open to the public, so the Met’s workshop of Scott Wheeler’s The Sorrows of Frederick is not on the list. -

Any Palet I L’Any Palet, Que Durant Tot El 2017 Faran, D’Aquest, Un Homenatge De Tots I Reivindicarà La Figura Del Tenor I La Per a Tots

ANY PALET 2017 MARTORELL JOSEP PALET 1877 · 1946 140è aniversari del naixement del tenor martorellenc Aquest 2017 es compleixen 140 anys El programa d’activitats que presentem del naixement del tenor Josep Palet, un té, per una banda, la ferma voluntat de MARTORELL 2017 dels cantants més universals de la història donar a conèixer arreu la persona de lírica catalana. Nascut a Martorell l’any Josep Palet i de divulgar-ne el seu 1877, amb tan sols 23 anys debutava llegat. Però, d’altra banda, hi ha la al Gran Teatre del Liceu i iniciava una convicció de voler omplir Martorell carrera internacional que el portaria d’òpera tot sentint les veus del moment per mig món. Afincat a Itàlia des de i, a més, impulsant la carrera de les l’any 1911, el tenor no es va oblidar noves promeses de la lírica. JOSEP PALET 1877 · 1946 mai de Martorell i a la seva mort, l’any A aquesta agenda s’hi sumaran, durant 1946, va ser anomenat Fill Predilecte tot el 2017, iniciatives provinents de di- de la vila. verses entitats i col·lectius de Martorell. L’Ajuntament de Martorell impulsa Propostes que s’uniran a l’Any Palet i l’Any Palet, que durant tot el 2017 faran, d’aquest, un homenatge de tots i reivindicarà la figura del tenor i la per a tots. realçarà novament. Qui és Josep Palet? Josep Palet va néixer a Martorell el 7 Tal va ser el vincle amb la seva vila L’èxit de Palet va ser posseir una veu de juny del 1877. -

Understanding the Lirico-Spinto Soprano Voice Through the Repertoire of Giovane Scuola Composers

UNDERSTANDING THE LIRICO-SPINTO SOPRANO VOICE THROUGH THE REPERTOIRE OF GIOVANE SCUOLA COMPOSERS Youna Jang Hartgraves Dissertation Prepared for the Degree of DOCTOR OF MUSICAL ARTS UNIVERSITY OF NORTH TEXAS August 2017 APPROVED: Jeffrey Snider, Major Professor William Joyner, Committee Member Silvio De Santis, Committee Member Stephen Austin, Chair of the Division of Vocal Studies Benjamin Brand, Director of Graduate Studies in the College of Music John Richmond, Dean of the College of Music Victor Prybutok, Dean of the Toulouse Graduate School Hartgraves, Youna Jang. Understanding the Lirico-Spinto Soprano Voice through the Repertoire of Giovane Scuola Composers. Doctor of Musical Arts (Performance), August 2017, 53 pp., 10 tables, 6 figures, bibliography, 66 titles. As lirico-spinto soprano commonly indicates a soprano with a heavier voice than lyric soprano and a lighter voice than dramatic soprano, there are many problems in the assessment of the voice type. Lirico-spinto soprano is characterized differently by various scholars and sources offer contrasting and insufficient definitions. It is commonly understood as a pushed voice, as many interpret spingere as ‘to push.’ This dissertation shows that the meaning of spingere does not mean pushed in this context, but extended, thus making the voice type a hybrid of lyric soprano voice type that has qualities of extended temperament, timbre, color, and volume. This dissertation indicates that the lack of published anthologies on lirico-spinto soprano arias is a significant reason for the insufficient understanding of the lirico-spinto soprano voice. The post-Verdi Italian group of composers, giovane scuola, composed operas that required lirico-spinto soprano voices. -

A Ricordo Dei Prodotti Lavorati Nell'ex Stabilimento Alimentare “Arrigoni” I

Servizio Toponomastica Progetto “CHI SONO?” note sui nomi delle vie di CESENA Scheda relativa a : RICCARDO ZANDONAI Riccardo Zandonai, compositore italiano, nacque a Rovereto in provincia di Trento nel 1883 da famiglia di umili origini. Fin dall'infanzia espresse un notevole talento musicale incoraggiato dal padre che suonava il flicorno baritono nella banda del paese. Tuttavia fino al 1894 non intraprese studi regolari di musica, ma familiarizzò con gli strumenti musicali che aveva a disposizione come la chitarra dello zio, il violino led il clarinetto nella banda ed un vecchio organo della chiesa. Dal 1894 al 1896 frequenta il Liceo di Rovereto e sembra che il brano intitolato "Serenata e Barcarola" del 1894 fosse la prova di ammissione alla classe del maestro Gianferrari. Zandonai prosegui gli studi musicali e si diplomò nel 1901 presso il Conservatorio di Pesaro, diretto da Pietro Mascagni. Nel 1908, Arrigo Boito, fiducioso del talento del giovane musicista lo presentò all’Editore Ricordi, che lo incaricò di comporre la sua prima opera lirica, la fiaba "Il grillo del focolare" con la quale Zandonai si impone all'attenzione del pubblico e della critica. Seguirono le opere "Conchita (1911)", "Melenis" (1912) e "Francesca da Rimini" (1914), dall’omonima tragedia di D’Annunzio, considerata il capolavoro di Zandonai, introducendo nel modo musicale italiano, imperniato sul melodramma verista, elementi del sinfonismo tedesco e dell'impressionismo musicale francese. Anche le successive opere di Zandonai, fra le quali "Giulietta e Romeo" (1921), "I cavalieri di Ekebù" (1923), "Giuliano" (1928), "Una partita" (1933)e "La farsa amorosa" (1933) contengono pagine di notevole freschezza ed inventiva. -

Performing Fascism: Opera, Politics, and Masculinities in Fascist Italy, 1935-1941

Performing Fascism: Opera, Politics, and Masculinities in Fascist Italy, 1935-1941 by Elizabeth Crisenbery Department of Music Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Bryan Gilliam, Advisor ___________________________ Benjamin Earle ___________________________ Philip Rupprecht ___________________________ Louise Meintjes ___________________________ Roseen Giles Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Music in the Graduate School of Duke University 2020 ABSTRACT Performing Fascism: Opera, Politics, and Masculinities in Fascist Italy, 1935-1941 by Elizabeth Crisenbery Department of Music Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Bryan Gilliam, Advisor ___________________________ Benjamin Earle ___________________________ Philip Rupprecht ___________________________ Louise Meintjes ___________________________ Roseen Giles An abstract of a dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Music in the Graduate School of Duke University 2020 Copyright by Elizabeth Crisenbery 2020 Abstract Roger Griffin notes that “there can be no term in the political lexicon which has generated more conflicting theories about its basic definition than ‘fascism’.” The difficulty articulating a singular definition of fascism is indicative of its complexities and ideological changes over time. This dissertation offers -

Francesca Da Rimini

PER INFORMAZIONI: cineteatro Agorà Piazza XXI Luglio, 29 Robecco S/N MI tel. 02 – 94975021 // 349 8253070 www.cineteatroagora.it AGORALIRICA 2012-2013 info@cine teatroagora.it Martedì 19 marzo 2013 ore 20:00 PROSSIMI APPUNTAMENTI de La grande opera al Cinema e la stagione teatrale. Riccardo Zandonai (1883 - 1944) Giovedì 18, Venerdì 19 aprile 2013, ore 21.00 FFrraanncceessccaa ddaa RRiimmiinnii CineTeatroAgorà Laboratorio permanente regia Ombretta Nai, Luca Stetur Anteprima Martedì 30 Aprile 2013 ore 20.00 dal Metropolitan Georg Friedrich Haendel ddaalllll MMeeeeetttttrrooppoollllliiiiitttttaann GIULIO CESARE IN EGITTO Opera in tre atti cantata in italiano. op.6, opera tragica in 4 atti e 5 quadri, libretto di Tito II Ricordi Con: Natalie Dessay, David Daniels, Alice Coote, Patricia (da Gabriele D'Annunzio) Bardon, Christophe Dumaux, Guido Loconsolo Personaggi Direzione musicale: Harry Bicket, Regia: David McVicar I figli di Guido Minore da Polenta Le donne di Francesca Giovedì 16, Venerdì 17 maggio 2013 21.00 Album dei ricordi Francesca (soprano) Biancofiore (soprano) Eppure un sorriso io l'ho regalato Eva-Maria Westbroek Garsenda (soprano) da un'idea di Elia Comincioli, Luca Comincioli, Marco Paolo il Bello (tenore) Altichiara (mezzosoprano) Comincioli, Andrea Maltagliati Marcello Giordani Donella (mezzosoprano)La schiava Giovanni lo Sciancato (baritono) (contralto)) Mark Delavan Ser Toldo Berardengo (tenore) Gli orari di inizio possono subire variazioni indipendenti dalla nostra volontà ma decisi Malatestino dall'Occhio (tenore) Il