Determining Stephen Sondheim's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

On the Leadership

2018 Annual Report RISEON THE LEADERSHIP NATIONAL BOARD OF TRUSTEES James A. Miller Thomas Schumacher Matt Conover, Chair Bartlett Wealth Management, Principal and Disney Theatrical Group, President Chairman Disney Parks Live Entertainment, Cincinnati, OH Vice President of Disneyland Entertainment Deborah Voigt Award-winning opera soprano Anaheim, CA Megan Tulac Phillips Hunter Bell, Vice Chair McKinsey & Company, Head of Marketing and ADVISORY BOARD Communications, Enterprise Agility Tony-nominated playwright, EdTA Board of San Francisco, CA Sarah Jane Arnegger Directors iHeart Radio Broadway, Director New York, NY John Prignano New York, NY Debbie Hill, Secretary Music Theatre International, COO and Director of Education and Development Aretta Baumgartner Community Arts Initiatives, Founder and New York, NY Center for Puppetry Arts, Education Director Executive Director Atlanta, GA Cincinnati, OH Kim Rogers Dori Berinstein Alex Birsh Concord Theatricals, Vice President, Amateur Licensing Dramatic Forces, Producer Playbill, Vice President and Chief Digital Officer New York, NY New York, NY New York, NY J. Jason Daunter Mark Drum David Redman Scott Disney Theatrical Group, Director of Theatrical Production Stage Manager Actor, Arts Advocate, EdTA Volunteer Licensing New York, NY New York, NY New York, NY Debby Gibbs Nancy Aborn Duffy ETF Legacy Circle Committee, Chair Educator, Former Broadway Licensing Abbie Van Nostrand Concord Theatricals, Vice President, Client Tupelo, MS Company Owner Relations & Community Engagement New York, NY -

Totalartwork

spınetL an Experiment on Gesamtkunstwerk Totalartwork Thursday–Friday October 21–22, 2004 The Cooper Union for the Advancement of Science and Art www.birgitramsauer.net/spinet 21 October 22 October Panel Discussion 6–7pm Panel Discussion 6–7pm Contemporary artists and an The Gesamtkunstwerk (Totalartwork) historical instrument in the 21st century Moderator: Moderator: Christopher McIntyre Christopher McIntyre Associate Music Curator, The Kitchen Associate Music Curator, The Kitchen Participants include: Jens Barnieck, pianist Participants include: Enrico Cocco, composer Jens Barnieck, pianist Gearoid Dolan, artist Enrico Cocco, composer Kyle Gann, composer, critic Gearoid Dolan, artist Thea Herold, word performer Thea Herold, word performer Charlie Morrow, composer Charlie Morrow, composer Aloisia Moser, philosopher Wolf-Dieter Neupert, company Wolf-Dieter Neupert, company for historical instruments for historical instruments Georg Nussbaumer, composer Georg Nussbaumer, composer Birgit Ramsauer, artist Birgit Ramsauer, artist Kartharina Rosenberger, Katharina Rosenberger, composer composer David Grahame Shane, architect, urbanist, author Concert 8pm Gerd Stern, poet and artist Gloria Coates Abraham Lincoln’s Performance 8pm Cooper Union Address* Frieder Butzmann Stefano Giannotti Soirée pour double solitaires * L’Arte des Paesaggio Charlie Morrow, alive I was silent Horst Lohse, Birgit’s Toy* and in death I do sing* Intermission Enrico Cocco, The Scene of Crime* Heinrich Hartl, Cemballissimo Aldo Brizzi, The Rosa Shocking* Katharina Rosenberger, -

Motion Picture

Moving Images Prepared by Bobby Bothmann RDA Moving Images by Robert L. Bothmann is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution- NonCommercial-ShareAlike 3.0 Unported License. Created 2 February 2013 Modified 11 November 2014 https://link.mnsu.edu/rda-video Scope Step-through view of the movie Hairspray from 2007 Generally in RDA rule order Uses MARC 21 examples Describing Manifestations & Items Follows RDA Chapters 2, 3, 4 Describing Works and Expressions Follows RDA Chapters 6, 7 Recording Attributes of Person & Corporate Body Uses RDA Chapters 9, 11, 18 Covers relator terms only Recording Relationships Follows RDA Chapters 24, 25, 26 2 Resources Olson, Nancy B., Robert L. Bothmann, and Jessica J. Schomberg. Cataloging of Audiovisual Materials and Other Special Materials: A Manual Based on AACR2 and MARC 21. Westport, Conn: Libraries Unlimited, 2008. [Short citation: CAVM] Online Audiovisual Catalogers, Inc. Cataloging Policy Committee. Streaming Media Best Practices Task Force. Best Practices for Cataloging Streaming Media. No place : OLAC CAPC, 2009. http://olacinc.org/drupal/capc_files/streamingmedia.pdf Online Audiovisual Catalogers, Inc. Cataloging Policy Committee. DVD Cataloging Guide Update Task Force. Guide to Cataloging DVD and Blu-ray Discs Using AACR2r and MARC 21. 2008 Update. No place: OLAC CAPC, 2008. http://olacinc.org/drupal/capc_files/DVD_guide_final.pdf Pan-Canadian Working Group on Cataloguing with RDA. “Workflow: Video recording (DVD) RDA.” In RDA Toolkit | Tools| Workflows |Global Workflows. 3 Preferred Source 4 5 Title Proper 2.3.2.1 RDA CORE the chief name of a resource (i.e., the title normally used when citing the resource). 245 10 $a Hairspray Capitalization is institutional and cataloger’s choice Describing Manifestations 6 Note on the Title Proper 2.17.2.3 RDA Make a note on the source from which the title proper is taken if it is a source other than: a) the title page, .. -

Download Transcript (PDF)

Larry Sidor Oral History Interview, November 6, 2015 Title “From Olympia to Deschutes to Crux: A Brewer's Life” Date November 6, 2015 Location Valley Library, Oregon State University. Summary In the interview, Sidor discusses his family background and rural upbringing in La Grande, Oregon, commenting on his father's activities as an OSU Extension Agent, his own boyhood interests in mechanical work, and the life histories of his mother and his siblings. From there, Sidor recounts his undergraduate years at Oregon State University, noting his switch in majors from Mechanical Engineering to Food Science, and commenting on the curriculum then available to undergraduates in the Food Science department. Sidor likewise reflects on the research that he conducted while a student and, in particular, his interest in winemaking during that time. From there, Sidor details the circumstances by which he declined a handful of job opportunities in the wine industry, opted instead to travel for a year in Europe, and began considering a career in brewing as a result of his experiences in Germany. He then traces his first connection with the Olympia Brewing Company; outlines his advancement within the company from packing quality control technician, to assistant brewmaster, to operations manager; shares his perspective on the brewing culture then prevalent at Olympia; and speaks of the connections that he made with hop growers in Washington and Oregon. Sidor next provides an overview of his years working at the S.S. Steiner company, shares his memories of the rise of microbreweries in the 1980s and 1990s, and reflects on the relationships that Steiner maintained with agricultural scientists at OSU. -

Scanned Using Scannx OS15000 PC

OHIO NEWS BUREAU INC. CLEVELAND, OHIO 44115 216/241-0675 COLUMBUS DISPBTCH COLUMBUS, OH, HM CIRC, 284,796 flPR-30-99 ^Night Music’ at ^^lOtterbein a lavish, lovely production By Midiael Grossberg Dispatch Theater Critic Shimmering with beauty, melody Theater review wit, A Little Night Music be A UWb NlgM HibIc, Otterbein comes a jeweled music box in the College's student production of deft hands of Otterbein College’s composer-lyricist Stephen Sondheim theater and music departments. ard author Hugh Wheeler’s musical. ' Lavish but unerringly tasteful, Directed by Dennis Romer. lovely but not gaudy, comically .................. Allison Sattinger broad but often delightfully subtle, Madame Armfeldt..... ...... Unda Dorff. the 'co-production ranks with Otter- Fredrik Egeiman ........Christopher Sloan'7 heir’s best spring musicals. Anne Egerman------ Ainanda Wheeler} ■ ■ Night Music is one of the most Cart-Magnus... .............. .Ayler Evan', ■challenging Stephen Sondheim Charlotte...... —... chrisi Carter ij “shows. Yet, Otterbein brings the ™ta............ ........... .... Jen Minter ,1973 Tony winner for best musical to Hennk................ Matthew DeVrienrt ^ftering life with grace, sophistica tion md seemingly effortless ease. Send In the bouquets - ..Director Dennis Romer and music Being performed at 8 tonight and ; director Kevin Purcell enhance the Saturday and 2 p.m. Sunday—and 7 wistful romanticism of Sondheim’s 8 p.m. May 6-8—in Cowan Hall, 30 ■< gorgeous score and author Hugh S. Grove Westerville. if. ,\yheeler’s portrait -

KS5 Exploring Performance Styles in Musical Theatre

Exploring performance KS5 styles in Musical Theatre Heidi McEntee Heidi McEntee is a Dance and KS5 – BTEC LEVEL 3, UNIT D10 Performing Arts specialist based in the Midlands. She has worked in education for over fifteen years delivering a variety of Dance and Performing Arts qualifications at Introduction Levels 1, 2 and 3. She is a Senior Unit D10: Exploring Performance Styles is one of the three units which sit within Module D: Assessment Associate working on musical theatre Skills Development from the new BTEC Level 3 in Performing Arts Practice Performing Arts qualifications and (musical theatre) qualification. This scheme of work focuses on the first unit which introduces a contributing author for student and explores different musical theatre styles. revision guides. This unit requires learners to develop their practical skills in dance, acting and singing while furthering their understanding of musical theatre styles. The unit culminates in a performance of two extracts in two different styles of musical theatre as well as a critical review of the stylistic qualities within these extracts. This scheme of work provides a suggested approach to six weeks of introductory classes, as a part of a full timetable, which explores the development of performance styles through the history of musical theatre via practical activities, short projects and research tasks. Learning objectives By the end of this scheme, learners will have: § Investigated the history of musical theatre and the factors which have influenced its development Unit D10: Exploring Performance § Explored the characteristics of different musical theatre styles and how they have developed Styles from BTEC L3 Nationals over time Performing Arts Practice (musical § Applied stylistic conventions to the performance of material theatre) (2019) § Examined professional work through critical analysis. -

Broadway Guest Artists & High-Profile Key Note Speakers

Broadway Guest Artists & High-Profile Key Note Speakers George Hamilton, Broadway and Film Actor, Broadway Actresses Charlotte D’Amboise & Jasmine Guy speaks at a Chicago Day on Broadway speak at a Chicago Day on Broadway Fashion Designer, Tommy Hilfiger, speaks at a Career Day on Broadway AMY WEINSTEIN PRESIDENT, CEO AND FOUNDER OF STUDENTSLIVE Amy Weinstein has been developing, creating, marketing and producing education programs in partnership with some of the finest Broadway Artists and Creative teams since 1998. A leader and pioneer in curriculum based standards and exciting and educational custom designed workshops and presentations, she has been recognized as a cutting edge and highly effective creative presence within public and private schools nationwide. She has been dedicated to arts and education for the past twenty years. Graduating from New York University with a degree in theater and communication, she began her work early on as a theatrical talent agent and casting director in Hollywood. Due to her expertise and comprehensive focus on education, she was asked to teach acting to at-risk teenagers with Jean Stapleton's foundation, The Academy of Performing and Visual Arts in East Los Angeles. Out of her work with these artistically talented and gifted young people, she co-wrote and directed a musical play entitled Second Chance, which toured as an Equity TYA contract to over 350,000 students in California and surrounding states. National mental health experts recognized the play as an inspirational arts model for crisis intervention, and interpersonal issues amongst teenagers at risk throughout the country. WGBH/PBS was so impressed with the play they commissioned it for adaptation to teleplay in 1996. -

Production Images Released for Hadestown at the National Theatre Click Here to Download

12 November 2018 Production images released for Hadestown at the National Theatre Click here to download Music, lyrics and book by Anaïs Mitchell Developed with Rachel Chavkin Olivier Theatre Press Night 13 November, in rep until 26 January Following record-breaking runs at New York Theatre Workshop and Canada’s Citadel Theatre, Hadestown comes to the National Theatre prior to Broadway. In the warmth of summertime, songwriter Orpheus and his muse Eurydice are living it up and falling in love. But as winter approaches, reality sets in: these young dreamers can’t survive on songs alone. Tempted by the promise of plenty, Eurydice is lured to the depths of industrial Hadestown. On a quest to save her, Orpheus journeys to the underworld where their trust in each other is put to a final test. Celebrated singer-songwriter Anaïs Mitchell and director Rachel Chavkin have transformed Mitchell’s acclaimed concept album into a genre-defying new musical that mixes modern American folk music with vintage New Orleans jazz to reimagine a sweeping ancient tale. ‘Inventive. Beguiling. Luminous. Spellbinding.’ – New York Times The cast includes Sharif Afifi, Reeve Carney, André De Shields, Rosie Fletcher, Amber Gray, Beth Hinton-Lever, Carly Mercedes Dyer, Eva Noblezada, Seyi Omooba, Gloria Onitiri, Patrick Page, Aiesha Pease, Joseph Prouse, Jordan Shaw and Shaq Taylor. Directed by Rachel Chavkin, with set design by Rachel Hauck, costume design by Michael Krass, lighting design by Bradley King, sound design by Nevin Steinberg and Jessica Paz, choreography by David Neumann, musical direction and vocal arrangements by Liam Robinson, orchestrations and arrangements by Michael Chorney and Todd Sickafoose, with Ken Cerniglia as dramaturg. -

1 the Recitative in Trombone Music William J. Stanley ©2019 at First

The Recitative in Trombone Music William J. Stanley ©2019 At first glance, the linking of recitative with a trombone might seem contradictory. After all, the recitative is found most often in opera and oratorio as a speech like style of musical expression performed by singers. But over the past several years, as I was preparing music for performance and assisting students with their preparation, recurring examples of recitative in trombone music appeared more than occasionally. Trombonists will readily recognize concertos by Ferdinand DaviD (1837), Launy Grøndahl (1924) and Gordon Jacob (1956) as often performed pieces that include a recitative. Nicolai Rimsky-Korsakov has provided two well-known solo recitatives for the orchestral second trombonist in Scheherazade, op. 35, and La Grande Pâque Russe, op. 36. These works and several others prompted, at first, an informal list to simply satisfy my curiosity. A subsequent more thorough search has found a large number of works that contain a recitative. To date well over 100 pieces have been discovereD. These span over 250 years and include unaccompanied solos, orchestral solos, pieces with piano, organ, orchestra and/or band accompaniment, and in various ensemble settings for tenor, bass and alto trombones. While that number and breadth of works might be surprising to some, the fact that composers have continued to use vocally influenceD materials in trombone music should be of no surprise to trombonists. We know there is the long tradition of the use of the trombone in vocal settings throughout its history. A thorough examination of this practice goes well beyond the scope and intent of this study, but it is widely known that the trombone was commonly used throughout the sixteenth- and seventeenth-centuries as an accompanying and doubling instrument in sacred settings with choirs. -

The Wicker Husband Education Pack

EDUCATION PACK 1 1 Contents Introduction Introduction ......................................................................................................................................................................... 3 Section 1: The Watermill’s Production of The Wicker Husband ........................................................................ 4 A Brief Synopsis.................................................................................................................................................................. 5 Character Profiles…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………....…8 Note from the Writer…………………………………………..………………………..…….……………………………..…………….10 Interview with the Director ………………………….……………………………………………………………………..………….. 13 Section 2: Behind the Scenes of The Watermill’s The Wicker Husband …………………………………..… ...... 15 Meet the Cast ................................................................................................................................................................... 16 An Interview with The Musical Director .................................................................................................................. .20 The Design Process ......................................................................................................................................................... 21 The Wicker Husband Costume Design ...................................................................................................................... 23 Be a Costume Designer……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..25 -

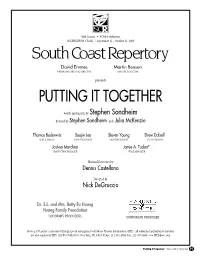

Putting It Together

46th Season • 437th Production SEGERSTROM STAGE / September 11 - October 11, 2009 David Emmes Martin Benson Producing ArtiStic director ArtiStic director presents PUTTING IT TOGETHER words and music by Stephen Sondheim devised by Stephen Sondheim and Julia McKenzie Thomas Buderwitz Soojin Lee Steven Young Drew Dalzell Scenic deSign coStume deSign Lighting deSign Sound deSign Joshua Marchesi Jamie A. Tucker* Production mAnAger StAge mAnAger musical direction by Dennis Castellano directed by Nick DeGruccio Dr. S.L. and Mrs. Betty Eu Huang Huang Family Foundation honorAry ProducerS corPorAte Producer Putting It Together is presented through special arrangement with music theatre international (mti). All authorized performance materials are also supplied by mti. 421 West 54th Street, new york, ny 10019; Phone: 212-541-4684 Fax: 212-397-4684; www.mtiShows.com Putting It Together• SOUTH COA S T REPE R TO R Y P1 THE CAST (in order of appearance) Matt McGrath* Harry Groener* Niki Scalera* Dan Callaway* Mary Gordon Murray* MUSICIANS Dennis Castellano (conductor/keyboards), John Glaudini (synthesizer), John Reilly (woodwinds), Louis Allee (percussion) SETTING A New York penthouse apartment. Now. LENGTH Approximately two hours including one 15-minute intermission. PRODUCTION STAFF Casting ................................................................................ Joanne DeNaut, CSA Dramaturg .......................................................................... Linda Sullivan Baity Assistant Stage Manager ............................................................. -

Desperate Housewives a Lot Goes on in the Strange Neighborhood of Wisteria Lane

Desperate Housewives A lot goes on in the strange neighborhood of Wisteria Lane. Sneak into the lives of five women: Susan, a single mother; Lynette, a woman desperately trying to b alance family and career; Gabrielle, an exmodel who has everything but a good m arriage; Bree, a perfect housewife with an imperfect relationship and Edie Britt , a real estate agent with a rocking love life. These are the famous five of Des perate Housewives, a primetime TV show. Get an insight into these popular charac ters with these Desperate Housewives quotes. Susan Yeah, well, my heart wants to hurt you, but I'm able to control myself! How would you feel if I used your child support payments for plastic surgery? Every time we went out for pizza you could have said, "Hey, I once killed a man. " Okay, yes I am closer to your father than I have been in the past, the bitter ha tred has now settled to a respectful disgust. Lynette Please hear me out this is important. Today I have a chance to join the human rac e for a few hours there are actual adults waiting for me with margaritas. Loo k, I'm in a dress, I have makeup on. We didn't exactly forget. It's just usually when the hostess dies, the party is off. And I love you because you find ways to compliment me when you could just say, " I told you so." Gabrielle I want a sexy little convertible! And I want to buy one, right now! Why are all rich men such jerks? The way I see it is that good friends support each other after something bad has happened, great friends act as if nothing has happened.