UNIVERSITY of CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Rethinking the Library

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Significance of Anime As a Novel Animation Form, Referencing Selected Works by Hayao Miyazaki, Satoshi Kon and Mamoru Oshii

The significance of anime as a novel animation form, referencing selected works by Hayao Miyazaki, Satoshi Kon and Mamoru Oshii Ywain Tomos submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Aberystwyth University Department of Theatre, Film and Television Studies, September 2013 DECLARATION This work has not previously been accepted in substance for any degree and is not being concurrently submitted in candidature for any degree. Signed………………………………………………………(candidate) Date …………………………………………………. STATEMENT 1 This dissertation is the result of my own independent work/investigation, except where otherwise stated. Other sources are acknowledged explicit references. A bibliography is appended. Signed………………………………………………………(candidate) Date …………………………………………………. STATEMENT 2 I hereby give consent for my dissertation, if accepted, to be available for photocopying and for inter-library loan, and for the title and summary to be made available to outside organisations. Signed………………………………………………………(candidate) Date …………………………………………………. 2 Acknowledgements I would to take this opportunity to sincerely thank my supervisors, Elin Haf Gruffydd Jones and Dr Dafydd Sills-Jones for all their help and support during this research study. Thanks are also due to my colleagues in the Department of Theatre, Film and Television Studies, Aberystwyth University for their friendship during my time at Aberystwyth. I would also like to thank Prof Josephine Berndt and Dr Sheuo Gan, Kyoto Seiko University, Kyoto for their valuable insights during my visit in 2011. In addition, I would like to express my thanks to the Coleg Cenedlaethol for the scholarship and the opportunity to develop research skills in the Welsh language. Finally I would like to thank my wife Tomoko for her support, patience and tolerance over the last four years – diolch o’r galon Tomoko, ありがとう 智子. -

Mimesis: Foot Washing from Luke to John

Ephemerides Theologicae Lovanienses 92/4 (2016) 655-670. doi: 10.2143/ETL.92.4.3183465 © 2016 by Ephemerides Theologicae Lovanienses. All rights reserved. Mimesis: Foot Washing from Luke to John Keith L. YODER University of Massachusetts at Amherst Introduction In this paper I argue that the Foot Washing of John 13,1-17, as literary composition, is a mimesis of the Sinful Woman narrative of Luke 7,36-501. Maurits Sabbe first proposed this mimetic association in 19822, followed by Thomas Brodie in 19933 and Ingrid Rosa Kitzberger in 19944, but the pro- posal dropped from view without ever being fully explored. Now a fresh comparison of the two texts uncovers a large array of previously unsurveyed parallels. Evaluation of old and new evidence will demonstrate that this is an instance of creative imitation, that combination of literary μίμησις (imi- tatio) and ζήλωσις (aemulatio) widely practiced by writers in antiquity5. Key directional indicators will point to Luke as the original and John as the emulation. I will here examine fifteen features in Luke that are paralleled in John. Throughout, I reference the internal tests for intertextual mimesis developed by Dennis R. MacDonald: the density, order, distinctiveness, and interpret- ability of the parallels6. Since external evidence pertinent to the relative dating of the Gospels of Luke and John is scarce and subject to debate, I will not address his tests of accessibility and analogy, but will focus instead on pointers of directionality arising from the internal evidence. 1. This paper was first presented at the March 2016 Annual Meeting of the Eastern Great Lakes Region of the Society of Biblical Literature, in Perrysville, Ohio, USA. -

Thoughts on Diegetic Music in the Early Operas of Zandonai1

DAVID ROSEN THOUGHTS ON DIEGETIC MUSIC IN THE EARLY OPERAS OF ZANDONAI1 Diegetic music – «music that (apparently) issues from a source within the narrative» (Gorbman, 23)2 – plays an important role in Zandonai’s early operas: not only does it appear frequently, but it often pushes the action forward, eliciting responses from the characters who hear it. And some of its uses are unusual, if not unprecedented. In this essay I focus on Il grillo del focolare but make cross-references to diegetic music in L’uccellino d’oro, Conchita, and Melenis as well. Readers unfamiliar with these operas may want to consult plot summaries, for example, in Dryden (469-79). Table 1 lists the passages referred to in this essay. 1 I want to express my thanks to the Centro internazionale di studi «Riccardo Zan- donai», especially to Diego Cescotti, Irene Comisso, and Federica Fortunato for assistance of all sorts before, during, and after the conference. Thanks go also to Gary Moulsdale for his comments on an earlier version of this text, to Ann Beck- man and other friends on WM-L (my favorite online opera discussion group) for answering some questions about precedents for certain uses of diegetic music, and to Carol Rosen for having translated into Italian the version of this essay that I delivered at the conference. 2 Citations refer to the Selective Bibliography at the end of this essay. The category ‘diegetic music’ thus includes both ‘musica in scena’ and ‘musica di scena’ (for the distinction see, for example, Girardi, 101-102). That is, it may include music emanating from offstage (whether in the wings or from the orchestra pit) or on- stage in full view of the audience. -

Double-Edged Imitation

Double-Edged Imitation Theories and Practices of Pastiche in Literature Sanna Nyqvist University of Helsinki 2010 © Sanna Nyqvist 2010 ISBN 978-952-92-6970-9 Nord Print Oy Helsinki 2010 Acknowledgements Among the great pleasures of bringing a project like this to com- pletion is the opportunity to declare my gratitude to the many people who have made it possible and, moreover, enjoyable and instructive. My supervisor, Professor H.K. Riikonen has accorded me generous academic freedom, as well as unfailing support when- ever I have needed it. His belief in the merits of this book has been a source of inspiration and motivation. Professor Steven Connor and Professor Suzanne Keen were as thorough and care- ful pre-examiners as I could wish for and I am very grateful for their suggestions and advice. I have been privileged to conduct my work for four years in the Finnish Graduate School of Literary Studies under the direc- torship of Professor Bo Pettersson. He and the Graduate School’s Post-Doctoral Researcher Harri Veivo not only offered insightful and careful comments on my papers, but equally importantly cre- ated a friendly and encouraging atmosphere in the Graduate School seminars. I thank my fellow post-graduate students – Dr. Juuso Aarnio, Dr. Ulrika Gustafsson, Dr. Mari Hatavara, Dr. Saija Isomaa, Mikko Kallionsivu, Toni Lahtinen, Hanna Meretoja, Dr. Outi Oja, Dr. Merja Polvinen, Dr. Riikka Rossi, Dr. Hanna Ruutu, Juho-Antti Tuhkanen and Jussi Willman – for their feed- back and collegial support. The rush to meet the seminar deadline was always amply compensated by the discussions in the seminar itself, and afterwards over a glass of wine. -

The 2020 Los Angeles Printers Fair

The 2020 Los Angeles Printers Fair To say 2020 has been an unusual year is certainly the grand understatement of the year! As much as all of us have been forced to live inside our boxes, the pandemic has really been an opportunity to think outside the comforts of our boxes and explore new ideas. Given that restrictions are still in place for us at the International Printing Museum, we have had to rethink how to connect with our community of creative souls who normally come together each fall for the Printers Fair. Like so many other events in our lives right now, this has meant creating a virtual experience but with a twist. So, welcome to the 12th annual 2020 VIRTUAL LOS ANGELES PRINTERS FAIR at the International Printing Museum (or in your living room or studio or apartment...). The Printing Museum team has worked hard to create an exceptional online event that captures some of the magic of visiting the Printers Fair in person; we are bringing our big tent of creative artisans to your screen this year. The Virtual Los Angeles Printers Fair is a wonderful opportunity to meet book artists, letterpress printers and printmakers and peruse their work. The beauty of this world known as Book Arts is that this is already a group thinking and working outside the modern boxes of our world, using traditional machines and methods but typically with a very modern twist. We have set up the PrintersFair.com website to give you as much of an opportunity to meet these creatives, see their shops and learn about their work. -

2007 University of Iowa

International Writing Program Annual Report 2007 University of Iowa Dedicated to the memory of Norine Zamastil Photos and graphics (from left to right) top row Kazuko Shiraishi (1976), calligraphy by Ramon Lim, Hauling and Paul Engle (1970s), Uli symbol second row from the top calligraphy by Cheryl Jacobsen, Elena Bossi (2007), Zapf dingbat, Veronique Tadjo and Mathilde Walter Clark (2006) second row from the bottom IWP participants on the Shambaugh House porch (2005), Uli symbol, Shambaugh House, calligraphy by Cheryl Jacobsen, ˆ bottom row peace sign,ˆ Arvind and Wandana Mehrotra (1971), calligraphy by Cheryl Jacobsen, Tomaz Salamun (1971) TABLE OF CONTENTS Greetings from Iowa City 2-3 The Fall Residency 4-7 Field Trips, Receptions, & Cultural Visits 8-9 Fall Residency Activities by Writer 10-12 Writer Portraits 13-15 The 40th Anniversary 16-17 Select Anniversary Schedule 18 2007 participants 19-25 The Middle East Reading Tour 26-34 Paros: The New Symposium 33-35 Program Support 37-41 Honor Roll of Contributors 42 Photos in this report are by Tom Langdon, Kelly Bedeian, IWP staff, and friends. GREETINGS FROM IOWA CITY A Letter from IWP Director Christopher Merrill. 2 The 40th session of the International Writing for writing and fellowship. Since then, the IWP Program (IWP) marked an extraordinary milestone has hosted nearly 1100 writers from more than in our program’s history. This fall, the IWP hosted 120 countries, making ours the oldest and largest forty writers from twenty-seven countries, who residency of its kind. At every turn, the IWP took part in one of the most dynamic residencies strives to connect artists; to create understanding ever. -

Live Auction Catalog

Live Auction Catalog 1 Calligraphy Session (2 Hours) Donated by Noriko and Temesgen Ready to try something new? This traditional Japanese calligraphy session holds up to 6 participants age 16 and up at Busch Center (AUUF compound). Participants submit English words of their choice and practice them in Japanese, first with pencils then with special calligraphy brushes. Three-week notice is required. 2 Etched Glass Artwork Donated by Deborah Strawn Titled "morning, morning glory". 11" x 13", etched, painted glass with found objects. 3 Buttermilk Blueberry Pancake Breakfast for Four Donated by Jim Bradley It's my Grandpa Bradley's pancake recipe, delightfully light. You can't stop eating them. Served with Wisconsin maple syrup, your choice of real or vegetarian bacon, orange juice, and a large selection of coffees and teas, decaf and regular. Coffee choices include non-machine made cappuccino and latte, made with Italian Lavazza coffee. Breakfast will be served at Jim and Sue's house. 4 Blackbirds Painting, by Melissa Blackburn Donated by Sharon Roberts Framed mixed-media painting with pastel backgrounds, by Melissa Blackburn 5 Halcyon Days Enamel Container (Unicorn in Captivity) Donated by Sharon Roberts This Halcyon Days container is 2.5" round, enameled with detail from the "Unicorn in Captivity" tapestry. 6 Chicago Style Deep Dish Pizza for Eight Donated by Carolyn Crowder Levy Menu: Charcuterie Plate, beer, wine, soft drinks, Anti-Pasta Salad, 3 deep dish pizzas, Vanilla Ice Cream with fresh Strawberries macerated in sugar and Sabra Liqueur 7 Computer Consultation Donated by Shannon Price Have the precious pages of your great American novel overloaded your computer memory? Or maybe you've worn out a few pieces of software transferring all of Grandma's recipes from yellowing index cards into Word files for your jump drive. -

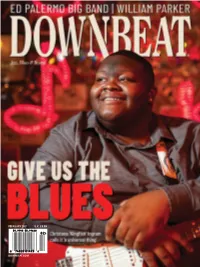

Downbeat.Com February 2021 U.K. £6.99

FEBRUARY 2021 U.K. £6.99 DOWNBEAT.COM FEBRUARY 2021 DOWNBEAT 1 FEBRUARY 2021 VOLUME 88 / NUMBER 2 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Reviews Editor Dave Cantor Contributing Editor Ed Enright Creative Director ŽanetaÎuntová Design Assistant Will Dutton Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Oakes ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile Vice President of Sales 630-359-9345 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney Vice President of Sales 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Grace Blackford 630-359-9358 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank-John Hadley; Chicago: Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Jeff Johnson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Sean J. O’Connell, Chris Walker, Josef Woodard, Scott Yanow; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Andrea Canter; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, Jennifer Odell; New York: Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Philip Freeman, Stephanie Jones, Matthew Kassel, Jimmy Katz, Suzanne Lorge, Phillip Lutz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Bill Milkowski, Allen Morrison, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Tom Staudter, Jack Vartoogian; Philadelphia: Shaun Brady; Portland: Robert Ham; San Francisco: Yoshi Kato, Denise Sullivan; Seattle: Paul de Barros; Washington, D.C.: Willard Jenkins, John Murph, Michael Wilderman; Canada: J.D. Considine, James Hale; France: Jean Szlamowicz; Germany: Hyou Vielz; Great Britain: Andrew Jones; Portugal: José Duarte; Romania: Virgil Mihaiu; Russia: Cyril Moshkow. -

Understanding Music Past and Present

Understanding Music Past and Present N. Alan Clark, PhD Thomas Heflin, DMA Jeffrey Kluball, EdD Elizabeth Kramer, PhD Understanding Music Past and Present N. Alan Clark, PhD Thomas Heflin, DMA Jeffrey Kluball, EdD Elizabeth Kramer, PhD Dahlonega, GA Understanding Music: Past and Present is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribu- tion-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. This license allows you to remix, tweak, and build upon this work, even commercially, as long as you credit this original source for the creation and license the new creation under identical terms. If you reuse this content elsewhere, in order to comply with the attribution requirements of the license please attribute the original source to the University System of Georgia. NOTE: The above copyright license which University System of Georgia uses for their original content does not extend to or include content which was accessed and incorpo- rated, and which is licensed under various other CC Licenses, such as ND licenses. Nor does it extend to or include any Special Permissions which were granted to us by the rightsholders for our use of their content. Image Disclaimer: All images and figures in this book are believed to be (after a rea- sonable investigation) either public domain or carry a compatible Creative Commons license. If you are the copyright owner of images in this book and you have not authorized the use of your work under these terms, please contact the University of North Georgia Press at [email protected] to have the content removed. ISBN: 978-1-940771-33-5 Produced by: University System of Georgia Published by: University of North Georgia Press Dahlonega, Georgia Cover Design and Layout Design: Corey Parson For more information, please visit http://ung.edu/university-press Or email [email protected] TABLE OF C ONTENTS MUSIC FUNDAMENTALS 1 N. -

Typography for Scientific and Business Documents

Version 1.8 Typography for Scientific and Business Documents George Yefchak Agilent Laboratories What’s the Big Deal? This paper is about typography. But first, I digress… inch marks, so you’ll probably get to enter those manually anyway.† Nothing is perfect…) Most of us agree that the use of correct grammar — or at In American English, punctuation marks are usually placed least something approaching it — is important in our printed before closing quotes rather than after them (e.g. She said documents. Of course “printed documents” refers not just to “No!”). But don’t do this if it would confuse the message words printed on paper these days, but also to things distrib- (e.g. Did she say “no!”?). Careful placement of periods and uted by slide and overhead projection, electronic broadcast- commas is particularly important when user input to ing, the web, etc. When we write something down, we computers is described: usually make our words conform to accepted rules of For username, type “john.” Wrong grammar for a selfish reason: we want the reader to think we For username, type “john”. ok know what we’re doing! But grammar has a more fundamen- tal purpose. By following the accepted rules, we help assure For username, type john . Even better, if font usage that the reader understands our message. is explained If you don’t get into the spirit of things, you might look at Dashes typography as just another set of rules to follow. But good The three characters commonly referred to as “dashes” are: typography is important, because it serves the same two purposes as good grammar. -

Narrative Theory

NARRATIVE THEORY EDITED BY JAMES PHELAN AND PETER J. RABINOWITZ A Companion to Narrative Theory Blackwell Companions to Literature and Culture This series offers comprehensive, newly written surveys of key periods and movements and certain major authors, in English literary culture and history. Extensive volumes provide new perspectives and positions on contexts and on canonical and postcanoni- cal texts, orientating the beginning student in new fields of study and providing the experienced undergraduate and new graduate with current and new directions, as pioneered and developed by leading scholars in the field. 1 A Companion to Romanticism Edited by Duncan Wu 2 A Companion to Victorian Literature and Culture Edited by Herbert F. Tucker 3 A Companion to Shakespeare Edited by David Scott Kastan 4 A Companion to the Gothic Edited by David Punter 5 A Feminist Companion to Shakespeare Edited by Dympna Callaghan 6 A Companion to Chaucer Edited by Peter Brown 7 A Companion to Literature from Milton to Blake Edited by David Womersley 8 A Companion to English Renaissance Literature and Culture Edited by Michael Hattaway 9 A Companion to Milton Edited by Thomas N. Corns 10 A Companion to Twentieth-Century Poetry Edited by Neil Roberts 11 A Companion to Anglo-Saxon Literature and Culture Edited by Phillip Pulsiano and Elaine Treharne 12 A Companion to Restoration Drama Edited by Susan J. Owen 13 A Companion to Early Modern Women’s Writing Edited by Anita Pacheco 14 A Companion to Renaissance Drama Edited by Arthur F. Kinney 15 A Companion to Victorian Poetry Edited by Richard Cronin, Alison Chapman, and Antony H. -

New Exception for Parody

Response to first batch Draft Legislation to modernise copyright exceptions published for technical review (See http://www.ipo.gov.uk/types/hargreaves/hargreaves-copyright/hargreaves- copyright-techreview.htm) Background This is a collaborative submission from a group of academics based in the UK with expertise in intellectual property and information technology law and related areas. The preparation of this response has been funded by (1) British and Irish Law, Education and Technology Association (“BILETA”) http://www.bileta.ac.uk/default.aspx and (2) CREATe (Creativity, Regulation Enterprise and Technology) the RCUK Centre for Copyright and New Business Models in the Creative Economy http://www.create.ac.uk/ This response has been prepared by Fiona Grant and Kim Barker. Fiona Grant is Lecturer in Law at the University of Abertay. She specialises in intellectual property and information technology. Kim Barker is Teaching Fellow at the University of Birmingham. She specialises in intellectual property and information technology. This response has been approved by the Executive of BILETA (the British and Irish Law, Education and Technology Association http://www.bileta.ac.uk/default.aspx) and is therefore submitted on behalf of BILETA. This response has been approved by the Management Committee of CREATe (http://www.create.ac.uk) and is therefore submitted on behalf of CREATe. In addition, this response is submitted by the following individuals: Dr Abbe Brown, University of Aberdeen Mr Felipe Romero Moreno, Oxford Brookes University Dr Phoebe Li, University of Sussex New exception for parody 1. Adopting this exception will give people in the UK’s creative industries greater freedom to use others’ works for parody purposes.