INTERNATIONAL COLLECTIVE in SUPPPRT of FISHWORKERS Contents SAMUDRA No

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PUB. 143 Sailing Directions (Enroute)

PUB. 143 SAILING DIRECTIONS (ENROUTE) ★ WEST COAST OF EUROPE AND NORTHWEST AFRICA ★ Prepared and published by the NATIONAL GEOSPATIAL-INTELLIGENCE AGENCY Springfield, Virginia © COPYRIGHT 2014 BY THE UNITED STATES GOVERNMENT NO COPYRIGHT CLAIMED UNDER TITLE 17 U.S.C. 2014 FIFTEENTH EDITION For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Internet: http://bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512-1800; DC area (202) 512-1800 Fax: (202) 512-2250 Mail Stop: SSOP, Washington, DC 20402-0001 II Preface date of the publication shown above. Important information to amend material in the publication is updated as needed and 0.0 Pub. 143, Sailing Directions (Enroute) West Coast of Europe available as a downloadable corrected publication from the and Northwest Africa, Fifteenth Edition, 2014 is issued for use NGA Maritime Domain web site. in conjunction with Pub. 140, Sailing Directions (Planning Guide) North Atlantic Ocean and Adjacent Seas. Companion 0.0NGA Maritime Domain Website volumes are Pubs. 141, 142, 145, 146, 147, and 148. http://msi.nga.mil/NGAPortal/MSI.portal 0.0 Digital Nautical Charts 1 and 8 provide electronic chart 0.0 coverage for the area covered by this publication. 0.0 Courses.—Courses are true, and are expressed in the same 0.0 This publication has been corrected to 4 October 2014, manner as bearings. The directives “steer” and “make good” a including Notice to Mariners No. 40 of 2014. Subsequent course mean, without exception, to proceed from a point of or- updates have corrected this publication to 24 September 2016, igin along a track having the identical meridianal angle as the including Notice to Mariners No. -

Coca-Cola La Historia Negra De Las Aguas Negras

Coca-Cola La historia negra de las aguas negras Gustavo Castro Soto CIEPAC COCA-COLA LA HISTORIA NEGRA DE LAS AGUAS NEGRAS (Primera Parte) La Compañía Coca-Cola y algunos de sus directivos, desde tiempo atrás, han sido acusados de estar involucrados en evasión de impuestos, fraudes, asesinatos, torturas, amenazas y chantajes a trabajadores, sindicalistas, gobiernos y empresas. Se les ha acusado también de aliarse incluso con ejércitos y grupos paramilitares en Sudamérica. Amnistía Internacional y otras organizaciones de Derechos Humanos a nivel mundial han seguido de cerca estos casos. Desde hace más de 100 años la Compañía Coca-Cola incide sobre la realidad de los campesinos e indígenas cañeros ya sea comprando o dejando de comprar azúcar de caña con el fin de sustituir el dulce por alta fructuosa proveniente del maíz transgénico de los Estados Unidos. Sí, los refrescos de la marca Coca-Cola son transgénicos así como cualquier industria que usa alta fructuosa. ¿Se ha fijado usted en los ingredientes que se especifican en los empaques de los productos industrializados? La Coca-Cola también ha incidido en la vida de los productores de coca; es responsable también de la falta de agua en algunos lugares o de los cambios en las políticas públicas para privatizar el vital líquido o quedarse con los mantos freáticos. Incide en la economía de muchos países; en la industria del vidrio y del plástico y en otros componentes de su fórmula. Además de la economía y la política, ha incidido directamente en trastocar las culturas, desde Chamula en Chiapas hasta Japón o China, pasando por Rusia. -

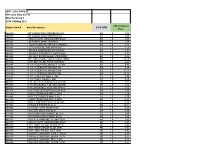

NPP / LOC RFP525 Effective Date 6/1/18 Attachment A-1 2018

NPP / LOC RFP525 Effective Date 6/1/18 Attachment A-1 2018 Catalog List 2018 Contract Staples Item # Item Description 2018 UOM Price 505299 .5IN VUSION RING BINDER BLACK EA $ 3.03 505309 .5IN VUSION RING BINDER BLUE EA $ 3.03 648823 1 HEAVY-DUTY VIEW BINDER BLUE EA $ 7.63 576442 1 IN BINDER SPINE INSERTS PK $ 2.79 751485 1 TOUCHGARD ANTIM VIEW BINDER EA $ 4.41 751486 1.5 TOUCHGARD ANTIM BINDER EA $ 5.38 648821 1.5IN BLK BTRBINDER WVIEWWIN EA $ 8.72 648813 1.5IN WHT BTRBINDER WVIEWWIN EA $ 8.72 943634 1.5IN WHT EXPRSSLOAD VIEWBNDR EA $ 4.52 344108 100% RECYCLED CLEAR FRONT REPO BX $ 15.15 482504 10-PK RECYCLED PORT NATURAL PK $ 2.66 737667 11 X 17 CLEARVUE BINDER 1.5 WH EA $ 9.77 737668 11 X 17 CLEARVUE BINDER 1IN EA $ 8.88 737670 11 X 17 CLEARVUE BINDER 2IN EA $ 11.11 737669 11 X 17 CLEARVUE BINDER 3IN EA $ 13.34 737672 11 X 17 POLY DIVIDER 8 TAB ST $ 2.92 737671 11 X 17 POLY INDEX 5 TAB ST $ 2.50 905234 11IN TOP FSTN PRONG FLD 2PK BK PK $ 3.54 805609 11X17 ERASABLE 8 TB INDX WHITE ST $ 2.08 805607 11X17 ERASABLE INDX TBS WHITE ST $ 1.66 797123 11X17 TABLOID PORTFOLIO BLACK EA $ 2.08 924529 1IN BETTERBINDER MINI BLACK EA $ 6.70 924443 1IN BETTERBINDER MINI BLUE EA $ 6.70 924439 1IN BETTERBINDER MINI WHITE EA $ 6.52 648819 1IN BLK BTR BINDER W VIEW WIN EA $ 7.63 473983 1IN EASLE BINDER BLACK EA $ 19.94 360968 1IN FRAME VIEW BINDER BK EA $ 5.75 586243 1IN LEGAL BINDER BLACK EA $ 5.46 515187 1IN VUSION RING BINDER BLACK EA $ 2.93 515186 1IN VUSION RING BINDER BLUE EA $ 2.93 648812 1IN WHT BTRBINDER W VIEW WIN EA $ 7.63 648833 2 HEAVY-DUTY -

Traceability Study in Shark Products

Traceability study in shark products Dr Heiner Lehr (Photo: © Francisco Blaha, 2015) Report commissioned by the CITES Secretariat This publication was funded by the European Union, through the CITES capacity-building project on aquatic species Contents 1 Summary.................................................................................................................................. 7 1.1 Structure of the remaining document ............................................................................. 9 1.2 Acknowledgements ....................................................................................................... 10 2 The market chain ................................................................................................................... 11 2.1 Shark Products ............................................................................................................... 11 2.1.1 Shark fins ............................................................................................................... 12 2.1.2 Shark meat ............................................................................................................. 12 2.1.3 Shark liver oil ......................................................................................................... 13 2.1.4 Shark cartilage ....................................................................................................... 13 2.1.5 Shark skin .............................................................................................................. -

Achieving Blue Growth Building Vibrant Fisheries and Aquaculture Communities Contents

Achieving Blue Growth Building vibrant fisheries and aquaculture communities Contents The Blue Growth Initiative 1 Supporting Blue Communities 2 Food and nutrition 4 Livelihoods and decent work 6 Safeguarding ecosystems and services 8 The Code of Conduct for Responsible Fisheries 10 Fighting illegal, unreported and unregulated (IUU) fishing 12 Inland fisheries 14 Aquaculture 16 Towards a more sustainable seafood value chain 18 Food loss and waste (Save Food) 20 Ecolabels and certification 22 Technology and innovation 24 “ Harnessing the power of the sea to improve social and economic development of populations, while simultaneously safeguarding marine resources and promoting environmental sustainability, is imperative as we move towards a world approaching 10 billion by 2050. We look forward to our continued collaboration with member countries in achieving Blue Growth through policies and implementation of development programmes in fisheries and aquaculture.” Árni M. Mathiesen, Assistant Director-General, FAO Fisheries and Aquaculture Department The Blue Growth Initiative Fisheries and aquaculture support the livelihoods of millions of people around the world in rural and coastal communities, and often play a key role in a society’s culture and identity. As these communities know well, fish is also a healthy and nutritious food, with the potential to feed our growing planet. But as the population grows, the demand for fish increases, and our natural resources are increasingly under pressure, sustainable management and development is crucial to preserving these resources for future generations. Like the Green Economy principles that preceded it, FAO’s Blue Growth Initiative emphasizes the three pillars of sustainable development– economic, environmental and social – so that fisheries and aquaculture contribute to the 2030 Agenda Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). -

The Political Ecology of Crisis and Institutional Change: the Case of the Northern Cod1

The Political Ecology of Crisis and Institutional Change: 1 The Case of the Northern Cod by Bonnie J. McCay and Alan Christopher Finlayson Rutgers the State University, New Brunswick, New Jersey Presented to the Annual Meetings of the American Anthropological Association, Washington, D.C., November 15-19, 1995. A longer and different version, with Finlayson as first author, is to be published in Linking Social and Ecological Systems; Institutional Learning for Resilience. Fikret Berkes and Carl Folke, eds. on behalf of The Property Rights Programme, The Beijer International Institute of Ecological Economics, The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences. Introduction: Systems Crisis The question we pose, although cannot yet answer with certainty, is whether the current set of crises in fisheries--- from the salmon of the West Coast of North America to the groundfish of the East Coast of North America--will open the door to institutional- cultural, social, political- change. There are theoretical and logical grounds for thinking that crisis and institutional change might be linked (Holling 1986; Kuhn 1962, 1970) although the nature and outcomes of linkages are not so straightforward (Lee 1993). Fisheries management is a thoroughly modernist venture, imbued as are so many other of the applied "natural resource" areas with a very pragmatic, utilitarian, science- dependent, and mostly optimistic perspective on the ability of people to "manage" wild things and processes. Management decisions-such as quotas, the timing or length of a fishing season, and the kinds of fishing gear allowed-are influenced by many things but are in theory dependent on information and understandings from a probabilistic but deterministic science known as "stock assessment." However, the alarming occurrence of fish stock declines and collapses throughout the world is accompanied by critical appraisals of the specific tools and the more general philosophies of fisheries management. -

Hê Ritaskr⁄ 2005

HÍ Ritaskrá 2005 9.5.2006 11:19 Page 1 Ritaskrá Háskóla Íslands 2005 HÍ Ritaskrá 2005 9.5.2006 11:19 Page 2 Efnisyfirlit Contents Félagsvísindadeild . .7 Faculty of Social Sciences . .7 Bókasafns- og upplýsingafræði . .7 Library- and Information Science . .7 Félagsfræði . .9 Sociology . .9 Félagsráðgjöf . .12 Social worl . .12 Kynjafræði . .14 Gender Studies . .14 Mannfræði . .15 Anthropology . .15 Sálarfræði . .17 Psychology . .17 Stjórnmálafræði . .21 Political Science . .21 Uppeldis- og menntunarfræði . .24 Education . .24 Þjóðfræði . .28 Folkloristics . .24 Guðfræðideild . .30 Faculty of Theology . .30 Hjúkrunarfræðideild . .34 Faculty of Nursing . .34 Hjúkrunarfræði . .34 Nursing . .34 Ljósmóðurfræði . .42 Midwifery . .42 Hugvísindadeild . .44 Faculty of Humanities . .44 Bókmenntafræði- og málvísindi . .44 Comparative Literature and Linguistics . .44 Enska . .47 English . .47 Heimspeki . .48 Philosophy . .48 Íslenska . .51 Icelandic Language and Literature . .51 Rómönsk og klassísk mál . .55 Roman and Classicical Languages . .55 Sagnfræði . .57 History . .57 Þýska og norðurlandamál . .61 German and Nordic Languages . .61 Hugvísindastofnun . .62 Centre for Research in the Humanities . .62 Orðabók Háskólans . .64 Institute of Lexicography . .64 Stofnun Árna Magnússonar . .66 The Árni Magnússon Institute in Iceland . .66 Stofnun Sigurðar Nordals . .69 The Sigurður Nordal Institute . .69 Lagadeild . .71 Faculty of Law . .71 Lyfjafræðideild . .76 Faculty of Pharmacy . .76 Læknadeild . .82 Faculty of Medicine . .82 Augnsjúkdómafræði . .82 Ophthalmology . .82 Barnalæknisfræði . .86 Paediatrics . .86 Erfðafræði . .87 Genetics . .87 Frumulíffræði . .88 Cell Biology . .88 Fæðinga - og kvensjúkdómafræði . .89 Obstetrics and Gynaecology . .89 Geðlæknisfræði . .91 Psychiatry . .91 Handlæknisfræði . .91 Surgery and Orthopaedics . .91 Heilbrigðisfræði . .92 Preventive Medicine . .92 Heimilislæknisfræði . .93 Community Medicine . .93 Lífeðlisfræði . .93 Physiology . .93 Lífefnafræði . .95 Biological Chemistry . .95 Líffærafræði . -

"She's Gone, Boys": Vernacular Song Responses to the Atlantic Fisheries Crisis

"She's Gone, Boys": Vernacular Song Responses to the Atlantic Fisheries Crisis Peter Narváez Abstract: In July 1992 a moratorium on the commercial fishing of cod, the staple of the North Atlantic fisheries, urns enacted by the Government of Canada. Because of the continued decline in fish stocks, the moratorium has been maintained, and fishing for domestic personal consumption has also been prohibited. Various compensation programs have not atoned for the demise of what is regarded as a “way of life." Responding to the crisis, vernacular verse, mostly in song form from Newfoundland, reflects the inadequacies of such programs. In addition, these creations assign causes and solutions while revealing a common usage of musical style, language and signifiers which combine to affirm an allegiance to traditional collective values of family, community and province through nostalgic experience. Some of the versifiers have turned to the craft for the first time during this disaster because they view songs and recitations as appropriate vehicles for social commentary. Traditions of songmaking and versifying (NCARP, The Northern Cod Adjustment and responsive to local events (Mercer 1979; O'Donnell Recovery Program, August 1, 1992 to May 15, 1994, 1992: 132-47; Overton 1993; Sullivan 1994) continue and TAGS, The Atlantic Groundfish Strategy, May to thrive in Atlantic Canada, especially in 16, 1994 to May 15, 1999), these have not offset what Newfoundland. As with the sealing protests and is widely perceived as the loss of a traditional counter-protests of the 1970s (Lamson 1979), area "way of life." This study examines expressive residents view as a tragedy the latest event to responses to the fisheries crisis, largely in prompt vernacular poetics and music (i.e., elements Newfoundland, by analysing the lyrics of, at this of expressive culture the people of a particular point, 43 songs and 6 "recitations" (i.e., monologues: region identify as their own: cf. -

Marine Fishes from Galicia (NW Spain): an Updated Checklist

1 2 Marine fishes from Galicia (NW Spain): an updated checklist 3 4 5 RAFAEL BAÑON1, DAVID VILLEGAS-RÍOS2, ALBERTO SERRANO3, 6 GONZALO MUCIENTES2,4 & JUAN CARLOS ARRONTE3 7 8 9 10 1 Servizo de Planificación, Dirección Xeral de Recursos Mariños, Consellería de Pesca 11 e Asuntos Marítimos, Rúa do Valiño 63-65, 15703 Santiago de Compostela, Spain. E- 12 mail: [email protected] 13 2 CSIC. Instituto de Investigaciones Marinas. Eduardo Cabello 6, 36208 Vigo 14 (Pontevedra), Spain. E-mail: [email protected] (D. V-R); [email protected] 15 (G.M.). 16 3 Instituto Español de Oceanografía, C.O. de Santander, Santander, Spain. E-mail: 17 [email protected] (A.S); [email protected] (J.-C. A). 18 4Centro Tecnológico del Mar, CETMAR. Eduardo Cabello s.n., 36208. Vigo 19 (Pontevedra), Spain. 20 21 Abstract 22 23 An annotated checklist of the marine fishes from Galician waters is presented. The list 24 is based on historical literature records and new revisions. The ichthyofauna list is 25 composed by 397 species very diversified in 2 superclass, 3 class, 35 orders, 139 1 1 families and 288 genus. The order Perciformes is the most diverse one with 37 families, 2 91 genus and 135 species. Gobiidae (19 species) and Sparidae (19 species) are the 3 richest families. Biogeographically, the Lusitanian group includes 203 species (51.1%), 4 followed by 149 species of the Atlantic (37.5%), then 28 of the Boreal (7.1%), and 17 5 of the African (4.3%) groups. We have recognized 41 new records, and 3 other records 6 have been identified as doubtful. -

Canadian Arctic Sovereignty and Security

Journal of Military and Strategic Studies, Spring 2009, Vol. 11, Issue 3. IN DEFENCE OF DEFENCE: CANADIAN ARCTIC SOVEREIGNTY AND SECURITY LCol. Paul Dittmann, 3 Canadian Forces Flying Training School Since the Second World War, Canada‟s armed forces have often represented the most prominent federal organization in the occupation and use of the Canadian Arctic. Economic development in the region came in fits and starts, hindered by remoteness and the lack of any long-term industry base. Today the Arctic‟s resource potential, fuelled by innovative technological advances, has fed to demands for infrastructure development. New opportunities in Canada‟s Arctic have, in turn, influenced a growing young population and their need for increased social development. Simultaneously, the fragile environment becomes a global focal point as the realities of climate change are increasingly accepted, diplomatically drawing together circumpolar nations attempting to address common issues. A unipolar world order developed with the geopolitical imbalance caused by the fall of the Soviet Union. This left the world‟s sole superpower, the United States (US), and its allies facing increased regional power struggles, international terrorism, and trans-national crime. Given the combination of tremendous growth in the developing world, its appetite for commodities, and the accessibility to resource-rich polar regions facilitated by climate change, Canada faces security and sovereignty issues that are both remnants of the Cold War era and newly emerging. The response to these challenges has been a resurgence of military initiatives to empower Canadian security and sovereignty in the region. Defence-based initiatives ©Centre for Military and Strategic Studies, 2009. -

TRAFFIC Bulletin Volume 32, No. 1

TRAFFIC 1 BULLETIN VOL. 32 NO. 1 32 NO. VOL. TRAFFIC is a leading non-governmental organisation working globally on trade in wild animals and plants in the context of both biodiversity conservation and sustainable development. For further information contact: The Executive Director TRAFFIC David Attenborough Building Pembroke Street Cambridge CB2 3QZ UK Telephone: (44) (0) 1223 277427 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.traffic.org IMPACT OF TRADE AND CLIMATE CHANGE ON NARWHAL POPULATIONS With thanks to The Rufford Foundation for contributimg to the production costs of the TRAFFIC Bulletin DRIED SEAHORSES FROM AFRICA TO ASIA is a strategic alliance of APRIL 2020 EEL TRADE REVIEW The journal of TRAFFIC disseminates information on the trade in wild animal and plant resources 32(1) NARWHAL COVER FINAL.indd 1 05/05/2020 13:05:11 GLOBAL TRAFFIC was established TRAFFIC International David Attenborough Building, Pembroke Street, Cambridge, CB2 3QZ, UK. in 1976 to perform what Tel: (44) 1223 277427; E-mail: [email protected] AFRICA remains a unique role as a Central Africa Office c/o IUCN, Regional Office for Central Africa, global specialist, leading and PO Box 5506, Yaoundé, Cameroon. Tel: (237) 2206 7409; Fax: (237) 2221 6497; E-mail: [email protected] supporting efforts to identify Southern Africa Office c/o IUCN ESARO, 1st floor, Block E Hatfield Gardens, 333 Grosvenor Street, and address conservation P.O. Box 11536, Hatfield, Pretoria, 0028, South Africa Tel: (27) 12 342 8304/5; Fax: (27) 12 342 8289; E-mail: [email protected] challenges and solutions East Africa Office c/o WWF TCO, Plot 252 Kiko Street, Mikocheni, PO Box 105985, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. -

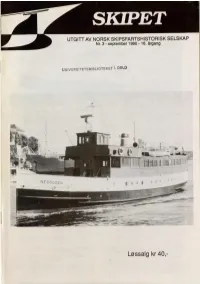

Løssalg Kr 40,- 2

UTGITT AV NORSK SK1PSFARTSHISTORISK SELSKAP Nr. 3 - september 1990 - 16. årgang UNIVERSITETSBIBLIOTEKET l OSLO m i, •<: Mån:5- $ «. fsj I* C' jj QQg* s. ; | | lii|l|Wi 111i W111'1 ,-innfifl i ~~~~ ,-::'^r - .. '>«**** Løssalg kr 40,- 2 NORSK SKIPSFARTSHISTORISK SELSKAP INNHOLD er en landsobfattende förening for skipsfarts A/S NESODDEN - BUNDEFJORD DAMPSKIPSSELSKAP interesserte. Föreningen arbeider for å stimu av Harald Lorentzen 4 lere interessen for norsk skipsfarts historie. BLACK DIAMOND LINE Medlemskap er åpent for alle og koster Kr. 150,- for 1990 (inkl. 4 nr. av SKIPET) av Dag Bakka Jr : 31 NORSKE SKIPSFORLIS 1920 Föreningens adresse: av Arne Ingar Tandberg 36 Norsk Skipsfartshistorisk Selskap FRIMERKESPALTEN Postboks 87 5046 RÅDAL av Arne Ingar Tandberg 51 NORSKE SKIPSFORLIS 1969 Postgiro: 0801 3 96 71 06 av Thor B. Melhus 52 Bankgiro: 5205.20.40930 OBSERVASJONER Formann: Per Alsaker Nebbeveien 15 ved Dag Bakka jr 59 5033 FYLLINGSDALEN VESTFOLD I tlf. 05/ 16 88 21 av Dag Bakka jr 67 Sekretær: Leif M. Skjærstad Postboks 70 DRIVGODS 59 5330 TJELDSTØ tlf. 05/ 38 91 11 MEDLEMSNYTT 71 RØKESAL0NGEN Kasserer: Leif K. Nordeide av Per Alsaker 72 Østre Hopsvegen 46 5043 HOP FISKEKROKEN tlf. 05/ 91 01 42 av Thor B. Melhus 76 Bibliotek: Alf Johan Kristiansen KJØP 0G SALG Mannes 4275 SÆVELANDSVIK av Thor B. Melhus 80 tlf. 04/ 81 50 98 SKIPSMATRIKKELEN 90 Foto-pool: Øyvind Johnsen Klokkarlia 17 A 5050 NESTTUN DEAD-LINE for neste nummer av SKIPET: tlf. 05/ 10 04 18 15. november 1990 SKIPET BIBLIOTEK.-KVET .DER PÅ BERGENS SJØFARTSMUSEUM utgitt av Følgende bibliotekkvelder i fastsatt Norsk Skipsfartshistorisk Selskap i høsthalvåret: Årgang 16 - NR.