Canadian Arctic Sovereignty and Security

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Crowds Greet the Premier I of Korea Ends

w &es4 Cbpq VOL. 9 NELSON B. C. SUNDAY MORNINO, AUGUST 28, 1910 NO 113 CROWDS GREET I THE PREMIER OF KOREA ENDS Sir Wilfrid Laurier Has Great When Touched Fingers, Ears Kingdom Will Be Annexed by Reception and Arms Drop Off Japan on Monday STREETS ARE TOWN OF ST. JOE EMPEROR CONSENTS WELL DECORATED IN GRAVE DANGER LTO ANNEXATION Triumphant Progress Through Idaho Militia to Fight Flames Will Retain Title of King- Illuminated Streets to Mr, -Freewater Now on Fire No Degredation for de Veber's Residence j —Dense Smoke Koreans Nelson received Sir Wilfrid .Laurler (Special to The Dally Newt.) SEOUL, Korea, Aug. 27—Lieut Gen last night with flags flying, banners SPOKANE, Aug. 27—Two hundred eral Terauchi Is the probable first waving, upward surging rockets, a thou Idaho, mllltla were dispatched today to governor general of Korea which will sand red, white and blue lights merrily St. Joe, forestjjflres there threatening be annexed by Japan on Monday. twinkling and to the exhIterating sounds the destruction of the town. The tim of exploding firecrackers, cheering ber comes close to the outskirts und Korean Sovereignty Ceases. crowds and the patriotic strains of the the town is irfJgrave peril. On the Bo* SEOUL, Aug. 27—The Associated city band. vllle branch lit the Milwaukee railway Press, it is said, states that Korean Huge Crowd 200 men are fighting the conflagration, sovereignty has ceased and that the Fully two thousand people crowded which Is moving north and is likely to Emperor of Japan, will become abso (the platform of the union depot from do enormous damage to timber. -

Report on Transformation: a Leaner NDHQ?

• INDEPENDENT AND INFORMED • AUTONOME ET RENSEIGNÉ ON TRACK The Conference of Defence Associations Institute • L’Institut de la Conférence des Associations de la Défense Autumn 2011 • Volume 16, Number 3 Automne 2011 • Volume 16, Numéro 3 REPORT ON TRANSFORMATION: A leaner NDHQ? Afghanistan: Combat Mission Closure Reflecting on Remembrance ON TRACK VOLUME 16 NUMBER 3: AUTUMN / AUTOMNE 2011 PRESIDENT / PRÉSIDENT Dr. John Scott Cowan, BSc, MSc, PhD VICE PRESIDENT / VICE PRÉSIDENT Général (Ret’d) Raymond Henault, CMM, CD CDA INSTITUTE BOARD OF DIRECTORS LE CONSEIL D’ADMINISTRATION DE L’INSTITUT DE LA CAD EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR / DIRECTEUR EXÉCUTIF Colonel (Ret) Alain M. Pellerin, OMM, CD, MA Admiral (Ret’d) John Anderson SECRETARY-TREASURER / SECRÉTAIRE TRÉSORIER Mr. Thomas d’Aquino Lieutenant-Colonel (Ret’d) Gordon D. Metcalfe, CD Dr. David Bercuson HONOURARY COUNSEL / AVOCAT-CONSEIL HONORAIRE Dr. Douglas Bland Mr. Robert T. Booth, QC, B Eng, LL B Colonel (Ret’d) Brett Boudreau DIRECTOR OF RESEARCH / Dr. Ian Brodie DIRECTEUR DE LA RECHERCHE Mr. Paul Chapin, MA Mr. Thomas S. Caldwell Mr. Mel Cappe PUBLIC AFFAIRS / RELATIONS PUBLIQUES Captain (Ret’d) Peter Forsberg, CD Mr. Jamie Carroll Dr. Jim Carruthers DEFENCE POLICY ANALYSTS / ANALYSTES DES POLITIQUES DE DÉFENSE Mr. Paul H. Chapin Ms. Meghan Spilka O’Keefe, MA Mr. Terry Colfer Mr. Arnav Manchanda, MA M. Jocelyn Coulon Mr. Dave Perry, MA Dr. John Scott Cowan PROJECT OFFICER / AGENT DE PROJET Mr. Dan Donovan Mr. Paul Hillier, MA Lieutenant-général (Ret) Richard Evraire Conference of Defence Associations Institute Honourary Lieutenant-Colonel Justin Fogarty 151 Slater Street, Suite 412A Ottawa ON K1P 5H3 Colonel, The Hon. -

The Political Ecology of Crisis and Institutional Change: the Case of the Northern Cod1

The Political Ecology of Crisis and Institutional Change: 1 The Case of the Northern Cod by Bonnie J. McCay and Alan Christopher Finlayson Rutgers the State University, New Brunswick, New Jersey Presented to the Annual Meetings of the American Anthropological Association, Washington, D.C., November 15-19, 1995. A longer and different version, with Finlayson as first author, is to be published in Linking Social and Ecological Systems; Institutional Learning for Resilience. Fikret Berkes and Carl Folke, eds. on behalf of The Property Rights Programme, The Beijer International Institute of Ecological Economics, The Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences. Introduction: Systems Crisis The question we pose, although cannot yet answer with certainty, is whether the current set of crises in fisheries--- from the salmon of the West Coast of North America to the groundfish of the East Coast of North America--will open the door to institutional- cultural, social, political- change. There are theoretical and logical grounds for thinking that crisis and institutional change might be linked (Holling 1986; Kuhn 1962, 1970) although the nature and outcomes of linkages are not so straightforward (Lee 1993). Fisheries management is a thoroughly modernist venture, imbued as are so many other of the applied "natural resource" areas with a very pragmatic, utilitarian, science- dependent, and mostly optimistic perspective on the ability of people to "manage" wild things and processes. Management decisions-such as quotas, the timing or length of a fishing season, and the kinds of fishing gear allowed-are influenced by many things but are in theory dependent on information and understandings from a probabilistic but deterministic science known as "stock assessment." However, the alarming occurrence of fish stock declines and collapses throughout the world is accompanied by critical appraisals of the specific tools and the more general philosophies of fisheries management. -

My Drift Title: Mark Harmon Written By: Jerry D

My Drift Title: Mark Harmon Written by: Jerry D. Petersen Date: 15 October 2019 Article Number: 319-2019-17 Besides Jeopardy! and Wheel of Fortune and most all Sports, the two regular TV shows I like to watch are NCIS and Criminal Minds. I decided to write this article about someone from these shows and I picked Mark Harmon because I find his life to be the most interesting. Family Thomas Mark Harmon was born in Burbank, California on September 2, 1951, which makes him 68 years old. He was the youngest of three children. His parents were Heisman Trophy–winning football player and broadcaster Tom Harmon and actress, model, artist, and fashion designer Elyse Knox. Harmon’s two older sisters are the late actress and painter Kristin Nelson, who was divorced from the late singer Rick Nelson, and actress and model Kelly Harmon, formerly married to car magnate John DeLorean. Yes, Mark’s dad was a famous football player at the Mark Harmon’s Parents University of Michigan. He played the halfback position Tom Harmon and wife from 1938 to 1940. He led the nation in scoring and was Elyse Knox a consensus All-American in both 1939 and 1940 and won the Heisman Trophy, the Maxwell Award, and the Associated Press Athlete of the Year award in 1940. His nickname was "Old 98" which I find somewhat unusual for a halfback! He played in the NFL for the Los Angeles Rams for a couple of seasons. He was also a military pilot and a sports broadcaster. He died at age 70 in Los Angeles. -

Table of Contents

TABLE OF CONTENTS THE CHRETIEN LEGACY Introduction .................................................. i The Chr6tien Legacy R eg W hitaker ........................................... 1 Jean Chr6tien's Quebec Legacy: Coasting Then Stickhandling Hard Robert Y oung .......................................... 31 The Urban Legacy of Jean Chr6tien Caroline Andrew ....................................... 53 Chr6tien and North America: Between Integration and Autonomy Christina Gabriel and Laura Macdonald ..................... 71 Jean Chr6tien's Continental Legacy: From Commitment to Confusion Stephen Clarkson and Erick Lachapelle ..................... 93 A Passive Internationalist: Jean Chr6tien and Canadian Foreign Policy Tom K eating ......................................... 115 Prime Minister Jean Chr6tien's Immigration Legacy: Continuity and Transformation Yasmeen Abu-Laban ................................... 133 Renewing the Relationship With Aboriginal Peoples? M ichael M urphy ....................................... 151 The Chr~tien Legacy and Women: Changing Policy Priorities With Little Cause for Celebration Alexandra Dobrowolsky ................................ 171 Le Petit Vision, Les Grands Decisions: Chr~tien's Paradoxical Record in Social Policy M ichael J. Prince ...................................... 199 The Chr~tien Non-Legacy: The Federal Role in Health Care Ten Years On ... 1993-2003 Gerard W . Boychuk .................................... 221 The Chr~tien Ethics Legacy Ian G reene .......................................... -

Hê Ritaskr⁄ 2005

HÍ Ritaskrá 2005 9.5.2006 11:19 Page 1 Ritaskrá Háskóla Íslands 2005 HÍ Ritaskrá 2005 9.5.2006 11:19 Page 2 Efnisyfirlit Contents Félagsvísindadeild . .7 Faculty of Social Sciences . .7 Bókasafns- og upplýsingafræði . .7 Library- and Information Science . .7 Félagsfræði . .9 Sociology . .9 Félagsráðgjöf . .12 Social worl . .12 Kynjafræði . .14 Gender Studies . .14 Mannfræði . .15 Anthropology . .15 Sálarfræði . .17 Psychology . .17 Stjórnmálafræði . .21 Political Science . .21 Uppeldis- og menntunarfræði . .24 Education . .24 Þjóðfræði . .28 Folkloristics . .24 Guðfræðideild . .30 Faculty of Theology . .30 Hjúkrunarfræðideild . .34 Faculty of Nursing . .34 Hjúkrunarfræði . .34 Nursing . .34 Ljósmóðurfræði . .42 Midwifery . .42 Hugvísindadeild . .44 Faculty of Humanities . .44 Bókmenntafræði- og málvísindi . .44 Comparative Literature and Linguistics . .44 Enska . .47 English . .47 Heimspeki . .48 Philosophy . .48 Íslenska . .51 Icelandic Language and Literature . .51 Rómönsk og klassísk mál . .55 Roman and Classicical Languages . .55 Sagnfræði . .57 History . .57 Þýska og norðurlandamál . .61 German and Nordic Languages . .61 Hugvísindastofnun . .62 Centre for Research in the Humanities . .62 Orðabók Háskólans . .64 Institute of Lexicography . .64 Stofnun Árna Magnússonar . .66 The Árni Magnússon Institute in Iceland . .66 Stofnun Sigurðar Nordals . .69 The Sigurður Nordal Institute . .69 Lagadeild . .71 Faculty of Law . .71 Lyfjafræðideild . .76 Faculty of Pharmacy . .76 Læknadeild . .82 Faculty of Medicine . .82 Augnsjúkdómafræði . .82 Ophthalmology . .82 Barnalæknisfræði . .86 Paediatrics . .86 Erfðafræði . .87 Genetics . .87 Frumulíffræði . .88 Cell Biology . .88 Fæðinga - og kvensjúkdómafræði . .89 Obstetrics and Gynaecology . .89 Geðlæknisfræði . .91 Psychiatry . .91 Handlæknisfræði . .91 Surgery and Orthopaedics . .91 Heilbrigðisfræði . .92 Preventive Medicine . .92 Heimilislæknisfræði . .93 Community Medicine . .93 Lífeðlisfræði . .93 Physiology . .93 Lífefnafræði . .95 Biological Chemistry . .95 Líffærafræði . -

"She's Gone, Boys": Vernacular Song Responses to the Atlantic Fisheries Crisis

"She's Gone, Boys": Vernacular Song Responses to the Atlantic Fisheries Crisis Peter Narváez Abstract: In July 1992 a moratorium on the commercial fishing of cod, the staple of the North Atlantic fisheries, urns enacted by the Government of Canada. Because of the continued decline in fish stocks, the moratorium has been maintained, and fishing for domestic personal consumption has also been prohibited. Various compensation programs have not atoned for the demise of what is regarded as a “way of life." Responding to the crisis, vernacular verse, mostly in song form from Newfoundland, reflects the inadequacies of such programs. In addition, these creations assign causes and solutions while revealing a common usage of musical style, language and signifiers which combine to affirm an allegiance to traditional collective values of family, community and province through nostalgic experience. Some of the versifiers have turned to the craft for the first time during this disaster because they view songs and recitations as appropriate vehicles for social commentary. Traditions of songmaking and versifying (NCARP, The Northern Cod Adjustment and responsive to local events (Mercer 1979; O'Donnell Recovery Program, August 1, 1992 to May 15, 1994, 1992: 132-47; Overton 1993; Sullivan 1994) continue and TAGS, The Atlantic Groundfish Strategy, May to thrive in Atlantic Canada, especially in 16, 1994 to May 15, 1999), these have not offset what Newfoundland. As with the sealing protests and is widely perceived as the loss of a traditional counter-protests of the 1970s (Lamson 1979), area "way of life." This study examines expressive residents view as a tragedy the latest event to responses to the fisheries crisis, largely in prompt vernacular poetics and music (i.e., elements Newfoundland, by analysing the lyrics of, at this of expressive culture the people of a particular point, 43 songs and 6 "recitations" (i.e., monologues: region identify as their own: cf. -

2010 Annual Report

2010 ANNUAL REPORT Table of Contents Letter from the President & CEO ......................................................................................................................5 About The Paley Center for Media ................................................................................................................... 7 Board Lists Board of Trustees ........................................................................................................................................8 Los Angeles Board of Governors ................................................................................................................ 10 Media Council Board of Governors ..............................................................................................................12 Public Programs Media As Community Events ......................................................................................................................14 INSIDEMEDIA Events .................................................................................................................................14 PALEYDOCFEST ......................................................................................................................................20 PALEYFEST: Fall TV Preview Parties ...........................................................................................................21 PALEYFEST: William S. Paley Television Festival ......................................................................................... 22 Robert M. -

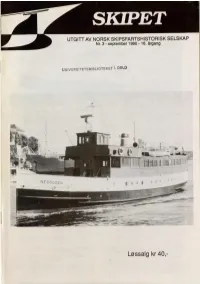

Løssalg Kr 40,- 2

UTGITT AV NORSK SK1PSFARTSHISTORISK SELSKAP Nr. 3 - september 1990 - 16. årgang UNIVERSITETSBIBLIOTEKET l OSLO m i, •<: Mån:5- $ «. fsj I* C' jj QQg* s. ; | | lii|l|Wi 111i W111'1 ,-innfifl i ~~~~ ,-::'^r - .. '>«**** Løssalg kr 40,- 2 NORSK SKIPSFARTSHISTORISK SELSKAP INNHOLD er en landsobfattende förening for skipsfarts A/S NESODDEN - BUNDEFJORD DAMPSKIPSSELSKAP interesserte. Föreningen arbeider for å stimu av Harald Lorentzen 4 lere interessen for norsk skipsfarts historie. BLACK DIAMOND LINE Medlemskap er åpent for alle og koster Kr. 150,- for 1990 (inkl. 4 nr. av SKIPET) av Dag Bakka Jr : 31 NORSKE SKIPSFORLIS 1920 Föreningens adresse: av Arne Ingar Tandberg 36 Norsk Skipsfartshistorisk Selskap FRIMERKESPALTEN Postboks 87 5046 RÅDAL av Arne Ingar Tandberg 51 NORSKE SKIPSFORLIS 1969 Postgiro: 0801 3 96 71 06 av Thor B. Melhus 52 Bankgiro: 5205.20.40930 OBSERVASJONER Formann: Per Alsaker Nebbeveien 15 ved Dag Bakka jr 59 5033 FYLLINGSDALEN VESTFOLD I tlf. 05/ 16 88 21 av Dag Bakka jr 67 Sekretær: Leif M. Skjærstad Postboks 70 DRIVGODS 59 5330 TJELDSTØ tlf. 05/ 38 91 11 MEDLEMSNYTT 71 RØKESAL0NGEN Kasserer: Leif K. Nordeide av Per Alsaker 72 Østre Hopsvegen 46 5043 HOP FISKEKROKEN tlf. 05/ 91 01 42 av Thor B. Melhus 76 Bibliotek: Alf Johan Kristiansen KJØP 0G SALG Mannes 4275 SÆVELANDSVIK av Thor B. Melhus 80 tlf. 04/ 81 50 98 SKIPSMATRIKKELEN 90 Foto-pool: Øyvind Johnsen Klokkarlia 17 A 5050 NESTTUN DEAD-LINE for neste nummer av SKIPET: tlf. 05/ 10 04 18 15. november 1990 SKIPET BIBLIOTEK.-KVET .DER PÅ BERGENS SJØFARTSMUSEUM utgitt av Følgende bibliotekkvelder i fastsatt Norsk Skipsfartshistorisk Selskap i høsthalvåret: Årgang 16 - NR. -

Bill C-55, Public Safety Act 2002

July 3, 2002 Hon. Martin Cauchon, P.C., M.P. Hon. David Collenette, P.C., M.P. Minister of Justice Minister of Transport Department of Justice Department of Transport East Memorial Building Tower C, Place de Ville 284 Wellington Street 29th floor, 330 Sparks Street Ottawa Ontario Ottawa, Ontario K1A 0A6 K1A 0N5 Hon. John McCallum, P.C., M.P. Hon. Lawrence MacAulay, P.C., M.P. Minister of National Defence Solicitor General Department of National Defence Department of the Solicitor General 101 Colonel By Drive 340 Laurier Avenue West Ottawa, Ontario Ottawa, Ontario K1A 0K2 K1A 0P8 Hon. Denis Coderre, P.C., M.P. Minister of Citizenship and Immigration Department of Citizenship and Immigration Jean Edmonds South Tower, 365 Laurier Avenue West, 21st Floor Ottawa, Ontario K1A 1L1 Dear Ministers: Re: Bill C-55, Public Safety Act 2002 The Canadian Bar Association (CBA) is pleased to have the opportunity to provide its comments concerning Bill C-55, Public Safety Act, 2002. Much of the Bill is similar to its predecessor – Bill C-42, Public Safety Act. To the extent that Bill C-55 has not addressed our concerns, we rely on our previous submission concerning Bill C-42 (a copy of which is attached), which we provided to the government in February 2002. This letter provides additional comments which principally address the differences between Bill C-42 and Bill C-55. Airline Passenger Information Bill C-42 permitted collection and use of airline passenger information in two contexts – transportation security (proposed section 4.82 of the Aeronautics Act, in clause 5 of Bill C-42) and immigration (proposed section 88.1 of the Immigration Act, in clause 69 of Bill C-42, which Page 2 applied to all transportation companies). -

Gibbs and His Team Investigate the Death of a Marine Who Captured His Own Death on Tape

GIBBS AND HIS TEAM INVESTIGATE THE DEATH OF A MARINE WHO CAPTURED HIS OWN DEATH ON TAPE “Caught on Tape” - #038 - The NCIS team is called to investigate when a Marine records his own murder on video as he falls off a cliff, on NCIS, Tuesday, February 22, 2005 (8:00-9:00 PM, ET/PT) on the CBS Television Network. Jeff Woolnough directed the episode from a script by Chris Crowe and John C. Kelley & Gil Grant. Gibbs and the team receive a call that a Marine has been found dead at the bottom of a cliff. When the team shows up to investigate the supposed hiking accident, they learn that he was on a camping trip with his wife and best friend (who they come to find out are having an affair). As Tony and McGee search through the forest for clues, McGee finds the murder weapon that proves the Marine’s death was not caused by his fall. Unfortunately, he finds this evidence in a patch of poison ivy. Gibbs pits the two lovers against each other in separate interrogation rooms to find out whose story is not adding up. Meanwhile Abby uses her superb technical skills to examine the video tape that reveals the Marine unknowingly recorded his own death post-mortem. CAST Leroy Jethro Gibbs.............................. MARK HARMON Kate Todd .................................. SASHA ALEXANDER Ducky Mallard .................................DAVID McCALLUM Tony DiNozzo.......................... MICHAEL WEATHERLY Abby Sciuto..................................PAULEY PERRETTE Timothy McGee .................................. SEAN MURRAY Press Contact: Jenny Rettig 323-933-3399 [email protected] Katie Sanseverino 323-933-3399 [email protected] Chris DiIorio 323-933-3399 [email protected] NCIS – Season 02. -

Geoffrey Bell Logbook 1909

T he Canadian POCKET DIARY 1909 PUBLISHED BY t h e B r o w n B r o s . LIMITED. MANUFACTURING STATIONERS . T O R O N T O . DOMINION OF CANADA Se a t o f Go v e r n m e n t —Ot t a w a . Ernest J. Lemaire, Chief Clerk and Private Secretary to Governor-General—His Excellency The Right Honourable Premier. Sir Arthur Henry George Earl Grey, Viscount Howick, High Commissioner for Canada in London—The Right Baron Grey of Howick, in the County of Northum Honourable Baron Strathcona and Mount Royal, G.C. berland, in the Peerage of the United Kingdom, and a M.G., LL.D. (Cantab.), 17 Victoria St., London, S.W. Baronet; Knight Grand Cross of the Most Distingui Sec’y., Can. Gov’t. Offices in London—W. J. Griffithe. shed Order of Saint Michael and Saint George, etc., etc. Asst. Secretary and Accountant—Arthur W. Reynolds. Staff.—Governor-General’s Secretary and Military Secre tary, Colonel J. Hanbury Williams, C.V.O., C.M.G.; DOMINION OF CANADA Aides-de-camp, Captain G. F. Trotter, D.S.O., Gren Formed of Ontario, Quebec, Nova Scotia and N.B. in 1867. adier Guards, Captain D. O. C. Newton, Duke of Manitoba and North-West Territories joined in 1870, Cambridge Own (Middlesex Regiment), Lieutenant British Columbia in 1871, Prince Edward Island in 1873. the Viscount Bury, Scots Guards; Comptroller of the The new Provinces of Alberta and Saskatchewan were Household, Major G. F. Paske, 3rd Oxfordshire Light created by special Act of Parliament, 1905.