Military Operations in Northern Luzon 1898-1901

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Military History Anniversaries 01 Thru 14 Feb

Military History Anniversaries 01 thru 14 Feb Events in History over the next 14 day period that had U.S. military involvement or impacted in some way on U.S military operations or American interests Feb 01 1781 – American Revolutionary War: Davidson College Namesake Killed at Cowan’s Ford » American Brigadier General William Lee Davidson dies in combat attempting to prevent General Charles Cornwallis’ army from crossing the Catawba River in Mecklenburg County, North Carolina. Davidson’s North Carolina militia, numbering between 600 and 800 men, set up camp on the far side of the river, hoping to thwart or at least slow Cornwallis’ crossing. The Patriots stayed back from the banks of the river in order to prevent Lieutenant Colonel Banastre Tartleton’s forces from fording the river at a different point and surprising the Patriots with a rear attack. At 1 a.m., Cornwallis began to move his troops toward the ford; by daybreak, they were crossing in a double-pronged formation–one prong for horses, the other for wagons. The noise of the rough crossing, during which the horses were forced to plunge in over their heads in the storm-swollen stream, woke the sleeping Patriot guard. The Patriots fired upon the Britons as they crossed and received heavy fire in return. Almost immediately upon his arrival at the river bank, General Davidson took a rifle ball to the heart and fell from his horse; his soaked corpse was found late that evening. Although Cornwallis’ troops took heavy casualties, the combat did little to slow their progress north toward Virginia. -

Colonial Contractions: the Making of the Modern Philippines, 1565–1946

Colonial Contractions: The Making of the Modern Philippines, 1565–1946 Colonial Contractions: The Making of the Modern Philippines, 1565–1946 Vicente L. Rafael Subject: Southeast Asia, Philippines, World/Global/Transnational Online Publication Date: Jun 2018 DOI: 10.1093/acrefore/9780190277727.013.268 Summary and Keywords The origins of the Philippine nation-state can be traced to the overlapping histories of three empires that swept onto its shores: the Spanish, the North American, and the Japanese. This history makes the Philippines a kind of imperial artifact. Like all nation- states, it is an ineluctable part of a global order governed by a set of shifting power rela tionships. Such shifts have included not just regime change but also social revolution. The modernity of the modern Philippines is precisely the effect of the contradictory dynamic of imperialism. The Spanish, the North American, and the Japanese colonial regimes, as well as their postcolonial heir, the Republic, have sought to establish power over social life, yet found themselves undermined and overcome by the new kinds of lives they had spawned. It is precisely this dialectical movement of empires that we find starkly illumi nated in the history of the Philippines. Keywords: Philippines, colonialism, empire, Spain, United States, Japan The origins of the modern Philippine nation-state can be traced to the overlapping histo ries of three empires: Spain, the United States, and Japan. This background makes the Philippines a kind of imperial artifact. Like all nation-states, it is an ineluctable part of a global order governed by a set of shifting power relationships. -

Afics BULLETIN New York

afics BULLETIN neW YorK ASSOCIATION OF FORMER INTERNATIONAL CIVIL SERVANTS Vol. 48 ♦ No. 2 ♦ Fall 2016 – Spring 2017 Photos by Mac Chiulli AFICS/NY members enjoy fine Cuban cuisine at Victor’s Café during annual winter luncheon, which also features presentation on the UN Food Garden. (See page 19.) “The mission of AFICS/NY is to support and promote the purposes, principles and programmes of the UN System; to advise and assist former international civil servants and those about to separate from service; to represent the interests of its members within the System; to foster social and personal relationships among members, to promote their well-being and to encourage mutual support of individual members." ASSOCIATION OF FORMER INTERNATIONAL CIVIL SERVANTS/NEW YorK HONORARY MEMBERS OthER BOARD MEMBERS Martti Ahtisaari J. Fernando Astete Kofi A. Annan Thomas Bieler Ban Ki-moon Gail Bindley-Taylor Aung San Suu Kyi Barbara Burns Javier Pérez de Cuéllar Mary Ann (Mac) Chiulli Ahsen Chowdury Frank Eppert GOVERNING BOARD Joan McDonald HONORARY MEMBERS Dr. Sudershan Narula Dr. Agnes Pasquier Andrés Castellanos del Corral Nancy Raphael O. Richard Nottidge Federico Riesco Edward Omotoso Warren Sach George F. Saddler Christine Smith-Lemarchand Linda Saputelli Gordon Tapper Jane Weidlund President of AFICS/NY Charities Foundation Anthony J. Fouracre OFFICERS President: John Dietz Office Staff Vice-Presidents: Deborah Landey, Jayantilal Karia Jamna Israni Velimir Kovacevic Secretary: Marianne Brzak-Metzler Deputy Secretary: Demetrios Argyriades Librarian Treasurer: Angel Silva Dawne Gautier CHANGE OF OFFICE STAFF In December 2016, we said goodbye to our part-time AFICS/ NY Office Staff member, Veronique Whalen, who has moved to Vienna, thanking her for her tremendous support to retirees and her special talent with everything to do with IT. -

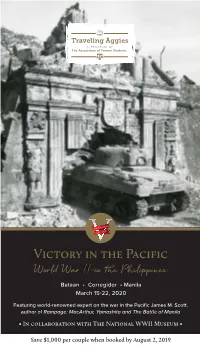

2020 Philippines A&M V2.Indd

y th Year of Victor Victory in the Pacific M A Y 19 4 World War II in the Philippines 5 Bataan • Corregidor • Manila March 15-22, 2020 Featuring world-renowned expert on the war in the Pacific James M. Scott, author of Rampage: MacArthur, Yamashita and The Battle of Manila • In collaboration with The National WWII Museum • Save $1,000 per couple when booked by August 2, 2019 1946 Corregidor Muster. Photo by James T. Danklefs ‘43 Howdy, Ags! On December 7, 1941, the Imperial Japanese Navy attacked the US Pacific Fleet The Traveling Aggies are pleased to partner with The National WWII Museum on at Pearl Harbor. Just a few hours later, the Philippines faced the same fury Victory in the Pacific: World War II in the Philippines. This fascinating journey will as the Japanese Army Air Force began bombing Clark Field, located north of begin in the lush province of Bataan, where tour participants will walk the first Manila. Five months later, the Japanese forced the Americans in the Philippines kilometer of the Death March and visit the remains of the prisoner of war camp at to surrender, but not before General MacArthur could slip away to Australia, Cabanatuan. On the island of Corregidor, 27 miles out in Manila Bay, guests will famously vowing, “I shall return.” see the blasted, skeletal remains of the mile-long barracks, theater, hospital, and officers’ quarters, as well as the monument built and dedicated by The Association After the fall of the Philippines, 70,000 captured American and Filipino soldiers near Malinta Tunnel in 2015, flying the Texas A&M flag and representing the were sent on the infamous “Bataan Death March,” a 65-mile forced march into sacrifice, bravery and Aggie Spirit of the men who Mustered there. -

The Great History

CAPAS The Great History Created in 1710, Capas is among the oldest towns of Tarlac together with Bamban (1710), Paniqui (1574) and Tarlac (1686). Its creation was justified by numerous settlements which were already established in the river banks of Cutcut River since the advent of the eighteenth century. The settlements belonged to the domain of Pagbatuan and Gudya; two sitios united by Capitan Mariano Capiendo when he founded the municipality. Historical records suggest three versions on how Capas got its name. The first version, as told, was originated from capas-capas, the “edible flower” similar to that of the caturay or the melaguas that abundantly grew along the Cutcut river banks. The second version, accordingly, was adapted from a “cotton tree” called capas, in Aeta dialect. The third version suggested that it was derived from the first three letters of the surnames of the town’s early settlers, namely: Capitulo, Capitly, Capiendo, Capuno, Caponga, Capingian, Caparas, Capera, Capunpue, Capit, Capil, Capunfuerza, Capunpun, Caputol, Capul and Capan. Assertively, they were called “caps” or “capas” in the local language. Between 1946-1951, registered barangays of Capas were Lawy, O’Donnell, Aranguren, Sto. Domingo, Talaga, Sta. Lucia, Bueno, Sta. Juliana, Sampucao, Calingcuan, Dolores and Manga, which were the 12 barrios during Late President Elpidio Quirino issued the Executive Order No. 486 providing “for the collection and compilation of historical data regarding barrios, towns, cities and provinces.” Today, Capas constitutes 20 barangays including all 12 except Calingcuan was changed to Estrada, Sampucao to Maruglu, Sto. Domingo was divided in two and barangays such as Sta. -

Joseph R. Mcmicking 1908 - 1990

JOSEPH R. MCMICKING 1908 - 1990 LEYTE LANDING OCTOBER, 20, 1944 THE BATTLE OF LEYTE GULF OCTOBER 23 TO 26, 1944 JOSEPH RALPH MCMICKING Joseph Ralph McMicking is known as a business maverick in three continents - his native Philippines, the United States and Spain. And yet, little is known about his service before and during World War II in the Pacific and even in the years following the war. A time filled with complete and utter service to the Philippine Commonwealth and the United States using his unique skills that would later on guide him in business. It was also a period of great personal sacrifice. He was born Jose Rafael McMicking in Manila on March 23, 1908, of Scottish-Spanish-Filipino descent. His father, lawyer Jose La Madrid McMick- ing, was the first Filipino Sheriff and Clerk of Court in American Manila, thereafter becoming the General Manager of the Insular Life Assurance Joe at 23 years old Company until his demise in early 1942. His mother was Angelina Ynchausti Rico from the Filipino business conglomerate of Ynchausti & Co. His early education started in Manila at the Catholic De la Salle School. He was sent to California for high school at the San Rafael Military Academy and went to Stanford University but chose to return to the Philippines before graduation. He married Mercedes Zobel in 1931 and became a General Manager of Ayala Cia, his wife’s Ynhausti, McMicking, Ortigas Family family business. He Joe is standing in the back row, 3rd from Right became a licensed pilot in 1932 and a part-time flight instructor with the newly-formed Philippine Army Air Corps in 1936. -

Province, City, Municipality Total and Barangay Population AURORA

2010 Census of Population and Housing Aurora Total Population by Province, City, Municipality and Barangay: as of May 1, 2010 Province, City, Municipality Total and Barangay Population AURORA 201,233 BALER (Capital) 36,010 Barangay I (Pob.) 717 Barangay II (Pob.) 374 Barangay III (Pob.) 434 Barangay IV (Pob.) 389 Barangay V (Pob.) 1,662 Buhangin 5,057 Calabuanan 3,221 Obligacion 1,135 Pingit 4,989 Reserva 4,064 Sabang 4,829 Suclayin 5,923 Zabali 3,216 CASIGURAN 23,865 Barangay 1 (Pob.) 799 Barangay 2 (Pob.) 665 Barangay 3 (Pob.) 257 Barangay 4 (Pob.) 302 Barangay 5 (Pob.) 432 Barangay 6 (Pob.) 310 Barangay 7 (Pob.) 278 Barangay 8 (Pob.) 601 Calabgan 496 Calangcuasan 1,099 Calantas 1,799 Culat 630 Dibet 971 Esperanza 458 Lual 1,482 Marikit 609 Tabas 1,007 Tinib 765 National Statistics Office 1 2010 Census of Population and Housing Aurora Total Population by Province, City, Municipality and Barangay: as of May 1, 2010 Province, City, Municipality Total and Barangay Population Bianuan 3,440 Cozo 1,618 Dibacong 2,374 Ditinagyan 587 Esteves 1,786 San Ildefonso 1,100 DILASAG 15,683 Diagyan 2,537 Dicabasan 677 Dilaguidi 1,015 Dimaseset 1,408 Diniog 2,331 Lawang 379 Maligaya (Pob.) 1,801 Manggitahan 1,760 Masagana (Pob.) 1,822 Ura 712 Esperanza 1,241 DINALUNGAN 10,988 Abuleg 1,190 Zone I (Pob.) 1,866 Zone II (Pob.) 1,653 Nipoo (Bulo) 896 Dibaraybay 1,283 Ditawini 686 Mapalad 812 Paleg 971 Simbahan 1,631 DINGALAN 23,554 Aplaya 1,619 Butas Na Bato 813 Cabog (Matawe) 3,090 Caragsacan 2,729 National Statistics Office 2 2010 Census of Population and -

The Armored Infantry Rifle Company

POWER AT THE PENTAGON-byPENTAGON4y Jack Raymond NIGHT DROP-The American Airborne Invasion $6.50 of Normandy-by S. 1.L. A. Marshall The engrossing story of one of 'thethe greatest power Preface by Carl Sandburg $6.50 centers thethe world has ever seen-how it came into Hours before dawn on June 6, 1944, thethe American being, and thethe people who make it work. With the 82dB2d and 1101Olst st Airborne Divisions dropped inin Normandy awesome expansion of military power in,in the interests behind Utah Beach. Their mission-to establish a firm of national security during the cold war have come foothold for the invading armies. drastic changes inin the American way of life. Mr. What followed isis one of the great and veritable Raymond says, "in the process we altered some of stories of men at war. Although thethe German defenders our traditionstraditions inin thethe military, in diplomacy, in industry, were spread thin, thethe hedgerow terrain favored them;them; science, education, politics and other aspects of our and the American successes when they eventually did society." We have developed military-civilian action come were bloody,bloody.- sporadic, often accidential. Seldom programs inin he farfar corners of the globe. Basic Western before have Americans at war been so starkly and military strategy depends upon decisions made in candidly described, in both theirtheir cowardice and theirtheir America. Uncle Sam, General Maxwell Taylor has courage. said, has become a world-renowned soldier in spite In these pages thethe reader will meet thethe officers whowho of himself. later went on to become our highest miliary com-com DIPLOMAT AMONG WARRIOR5-byWARRI0R-y Robert manders in Korea and after: J. -

World War Ii in the Philippines

WORLD WAR II IN THE PHILIPPINES The Legacy of Two Nations©2016 Copyright 2016 by C. Gaerlan, Bataan Legacy Historical Society. All Rights Reserved. World War II in the Philippines The Legacy of Two Nations©2016 By Bataan Legacy Historical Society Several hours after the bombing of Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941, the Philippines, a colony of the United States from 1898 to 1946, was attacked by the Empire of Japan. During the next four years, thou- sands of Filipino and American soldiers died. The entire Philippine nation was ravaged and its capital Ma- nila, once called the Pearl of the Orient, became the second most devastated city during World War II after Warsaw, Poland. Approximately one million civilians perished. Despite so much sacrifice and devastation, on February 20, 1946, just five months after the war ended, the First Supplemental Surplus Appropriation Rescission Act was passed by U.S. Congress which deemed the service of the Filipino soldiers as inactive, making them ineligible for benefits under the G.I. Bill of Rights. To this day, these rights have not been fully -restored and a majority have died without seeing justice. But on July 14, 2016, this mostly forgotten part of U.S. history was brought back to life when the California State Board of Education approved the inclusion of World War II in the Philippines in the revised history curriculum framework for the state. This seminal part of WWII history is now included in the Grade 11 U.S. history (Chapter 16) curriculum framework. The approval is the culmination of many years of hard work from the Filipino community with the support of different organizations across the country. -

War Crimes in the Philippines During WWII Cecilia Gaerlan

War Crimes in the Philippines during WWII Cecilia Gaerlan When one talks about war crimes in the Pacific, the Rape of Nanking instantly comes to mind.Although Japan signed the 1929 Geneva Convention on the Treatment of Prisoners of War, it did not ratify it, partly due to the political turmoil going on in Japan during that time period.1 The massacre of prisoners-of-war and civilians took place all over countries occupied by the Imperial Japanese Army long before the outbreak of WWII using the same methodology of terror and bestiality. The war crimes during WWII in the Philippines described in this paper include those that occurred during the administration of General Masaharu Homma (December 22, 1941, to August 1942) and General Tomoyuki Yamashita (October 8, 1944, to September 3, 1945). Both commanders were executed in the Philippines in 1946. Origins of Methodology After the inauguration of the state of Manchukuo (Manchuria) on March 9, 1932, steps were made to counter the resistance by the Chinese Volunteer Armies that were active in areas around Mukden, Haisheng, and Yingkow.2 After fighting broke in Mukden on August 8, 1932, Imperial Japanese Army Vice Minister of War General Kumiaki Koiso (later convicted as a war criminal) was appointed Chief of Staff of the Kwantung Army (previously Chief of Military Affairs Bureau from January 8, 1930, to February 29, 1932).3 Shortly thereafter, General Koiso issued a directive on the treatment of Chinese troops as well as inhabitants of cities and towns in retaliation for actual or supposed aid rendered to Chinese troops.4 This directive came under the plan for the economic “Co-existence and co-prosperity” of Japan and Manchukuo.5 The two countries would form one economic bloc. -

Department of Public Works and Highways

Department of Public Works and Highways Contract ID: 19CC0092 Contract Name: Package IV-2019 Construction of multi-purpose building Tiaong NHS Pulonggubat & Construction (Completion) of multi-purpose building Tiaong ES Location of the Contract: Guiguinto & Baliuag, Bulacan --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- CONTRACT AGREEMENT KNOW ALL MEN BY THESE PRESENTS: This CONTRACT AGREEMENT , made this _____20th________ of _____June___________, _ 2019_, by and between: The GOVERNMENT OF THE REPUBLIC OF THE PHILIPPINES through the Department of Public Works and Highways (DPWH) Bulacan First District Engineering Office represented herein by LORETA M. MALALUAN , duly authorized for this purpose, with main office address at Tikay, City of Malolos, Bulacan, hereinafter referred to as the “PROCURING ENTITY”; -and- ESN CONSTRUCTION AND TRADING , a single proprietorship organized and existing under and by virtue of laws of the Republic of the Philippines, with main office address at BrgyCity of Malolos, Bulacan , represented herein by ESPERANZA L. SADIE, duly authorized for this purpose, hereinafter referred to as the “CONTRACTOR;” WITNESSETH: WHEREAS , the PROCURING ENTITY is desirous that the CONTRACTOR execute the Works under Contract ID 19CC0092 - Package IV-2019 Construction of multi-purpose building Tiaong NHS Pulonggubat & Construction (Completion) of multi-purpose building Tiaong ES Guiguinto & Baliuag, Bulacan , hereinafter called the “Works ,” and the PROCURING ENTITY has accepted the Calculated Bid of the CONTRACTOR for the execution and completion of the Works at the calculated unit bid prices shown in the attached Bill of Quantities, or a total Contract price of Two Million Five Hundred Forty Four Thousand Seven Hundred Eighty Pesos and 80/100 (P2,544,780.80). NOW, THEREFORE , for and consideration of the foregoing premises, the parties hereto agree as follows: 1. -

Fma-Special-Issue Kali-Eskrima-Arnis

Publisher Steven K. Dowd Contributing Writers Leo T. Gaje, Jr Nick Papadakis Steven Drape Bot Jocano Contents From the Publishers Desk Kali Kali Means to Scrape Eskrima Arnis: A Question of Origins Filipino Martial Arts Digest is published and distributed by: FMAdigest 1297 Eider Circle Fallon, Nevada 89406 Visit us on the World Wide Web: www.fmadigest.com The FMAdigest is published quarterly. Each issue features practitioners of martial arts and other internal arts of the Philippines. Other features include historical, theoretical and technical articles; reflections, Filipino martial arts, healing arts and other related subjects. The ideas and opinions expressed in this digest are those of the authors or instructors being interviewed and are not necessarily the views of the publisher or editor. We solicit comments and/or suggestions. Articles are also welcome. The authors and publisher of this digest are not responsible for any injury, which may result from following the instructions contained in the digest. Before embarking on any of the physical activates described in the digest, the reader should consult his or her physician for advice regarding their individual suitability for performing such activity. From the Publishers Desk Kumusta This is a Special Issue that will raise some eyebrows. It seems that when you talk of Kali, Eskrima, or Arnis, there is controversy on where they came from and what they are about. And when you finally think you have the ultimate understanding then you find little things that add, change, subtract from the overall concept. Well in this Special Issue the FMAdigest obtained permission from the authors to take their explanation, some published years ago.