Middlebrow Cinema

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

CALENDAR January 23

BOWDOIN COLLEGE / ROMANCE LANGUAGES AND Cinema Studies CINE 2116 / SPAN 3116: Spanish Cinema: Taboo and Tradition Spring 2019 / MW 10:05 Elena Cueto Asín. Sills Hall 210 – 725‐3312 – email: [email protected] Office hours: Monday 2:45‐4, or by appointment. This course introduces students to film produced in Spain, from the silent era to the present, focusing on the ways in which cinema can be a vehicle for promoting social and cultural values, as well as for exposing social, religious, sexual, or historical taboos in the form of counterculture, protest, or as a means for society to process change or cope with issues from the past. Looks at the role of film genre, authorship, and narrative in creating languages for perpetuating or contesting tradition, and how these apply to the specific Spanish context. GRADE Class Participation 40% Essays 60% MATERIALS Film available on reserve at the LMC or/and on‐line. Readings on‐line and posted on blackboard CALENDAR January 23. Introduction January 28 ¡Átame! - Tie Me Up! Tie Me Down! (Pedro Almodóvar 1989) Harmony Wu “The Perverse Pleasures of Almodovar’s Átame” Journal of Spanish Cultural Studies 5 (3) 2004: 261-271. Reviews and controversy: New York Times: February 11, April 22 and 23, June 24, May 4, May 24, July 20 of 1989 January 30 Silent Cinema: The Unconventional and the Conventional El perro andaluz- Un Chien Andalou (Luis Buñuel 1927) Jordan Cox “Suffering as a Form of Pleasure: An Exploration of Black Humor in Un Chien Andalou” Film Matters 5(3) 2014: 14-18 February 4 and 6 La aldea maldita- The Cursed Village (Florian Rey 1929) Tatjana Pavlović 100 years of Spanish cinema [electronic resource] Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2009: 15-20 Sánchez Vidal, Agustin. -

Avance Largometrajes 2014Feature Films Preview

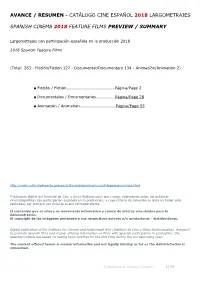

AVANCE / RESUMEN - CATÁLOGO CINE ESPAÑOL 2018 LARGOMETRAJES SPANISH CINEMA 2018 FEATURE FILMS PREVIEW / SUMMARY Largometrajes con participación española en la producción 2018 2018 Spanish Feature Films (Total: 263 - Ficción/Fiction 127 - Documental/Documentary 134 - Animación/Animation 2) ■ Ficción / Fiction…………………………………………Página/Page 2 ■ Documentales / Documentaries……………...Página/Page 28 ■ Animación / Animation……………………………..Página/Page 55 http://www.culturaydeporte.gob.es/cultura/areas/cine/mc/catalogodecine/inicio.html Publicación digital del Instituto de Cine y Artes Audiovisuales que recoge información sobre las películas cinematográficas con participación española en la producción, y cuyo criterio de selección se basa en haber sido calificadas por primera vez durante el año correspondiente. El contenido que se ofrece es meramente informativo y carece de efectos vinculantes para la Administración. El copyright de las imágenes pertenece a sus respectivos autores y/o productoras - distribuidoras. Digital publication of the Institute for Cinema and Audiovisual Arts (Instituto de Cine y Artes Audiovisuales), designed to promote Spanish films and mainly offering information on films with Spanish participation in production; the selection criteria are based on having been certified for the first time during the corresponding year. The content offered herein is merely informative and not legally binding as far as the Administration is concerned. © Ministerio de Cultura y Deporte 1 | 55 LARGOMETRAJES 2018 SPANISH FEATURE FILMS - FICCIÓN / FICTION #SEGUIDORES - #FOLLOWERS Dirección/Director: Iván Fernández de Córdoba Productoras/Prod. Companies: NAUTILUS FILMS & PROJECTS, S.L. Intérpretes/Cast: Sara Sálamo, Jaime Olías, Rodrigo Poisón, María Almudéver, Norma Ruiz y Aroa Ortigosa Drama 76’ No recomendada para menores de 12 años / Not recommended for audiences under 12 https://www.facebook.com/seguidoreslapelicula/ ; https://www.instagram.com/seguidoreslapelicula/ Tráiler: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RK5vUNlMJNc ¿QUÉ TE JUEGAS? - GET HER.. -

Rafael Azcona: Atrapados Por La Vida

Juan Carlos Frugone Rafael Azcona: atrapados por la vida 2003 - Reservados todos los derechos Permitido el uso sin fines comerciales Juan Carlos Frugone Rafael Azcona: atrapados por la vida Quiero expresar mi agradecimiento profundo a Cristina Olivares, Ignacio Darnaude Díaz, Fernando Lara y Manuela García de la Vega, quienes -de una u otra manera- me han ayudado para que este libro sea una realidad. También, por sus consejos, un agradecimiento para Luis Sanz y José Luis García Sánchez. Y ¿por qué no?, a Rafael Azcona, quien no concede nunca una entrevista, pero me concedió la riqueza irreproducible de muchas horas de su charla. Juan Carlos Frugone [5] Es absurdo preguntarle a un autor una explicación de su obra, ya que esta explicación bien puede ser lo que su obra buscaba. La invención de la fábula precede a la comprensión de su moraleja. JORGE LUIS BORGES [7] ¿Por qué Rafael Azcona? Rafael Azcona no sabe nada de cine. Porque ¿quién que sepa de cine puede negar su aporte indudable a muchas de las obras maestras del cine español e italiano de los últimos treinta años? Él lo niega. Todos sabemos que el cine es obra de un director, de la persona cuyo nombre figura a continuación de ese cartel que señala «un film de». Pero no deja de ser curioso que el común denominador de películas como El cochecito, El pisito, Plácido, El verdugo, Ana y los lobos, El jardín de las delicias, La prima Angélica, Break-up, La gran comilona, Tamaño natural, La escopeta nacional, El anacoreta, La corte de faraón y muchísimas más de la misma envergadura, sea el nombre y el apellido de Rafael Azcona. -

80 Years of Spanish Cinema Fall, 2013 Tuesday and Thursday, 9:00-10:20Am, Salomon 004

Brown University Department of Hispanic Studies HISP 1290J. Spain on Screen: 80 Years of Spanish Cinema Fall, 2013 Tuesday and Thursday, 9:00-10:20am, Salomon 004 Prof. Sarah Thomas 84 Prospect Street, #301 [email protected] Tel.: (401) 863-2915 Office hours: Thursdays, 11am-1pm Course description: Spain’s is one of the most dynamic and at the same time overlooked of European cinemas. In recent years, Spain has become more internationally visible on screen, especially thanks to filmmakers like Guillermo del Toro, Pedro Almodóvar, and Juan Antonio Bayona. But where does Spanish cinema come from? What themes arise time and again over the course of decades? And what – if anything – can Spain’s cinema tell us about the nation? Does cinema reflect a culture or serve to shape it? This course traces major historical and thematic developments in Spanish cinema from silent films of the 1930s to globalized commercial cinema of the 21st century. Focusing on issues such as landscape, history, memory, violence, sexuality, gender, and the politics of representation, this course will give students a solid training in film analysis and also provide a wide-ranging introduction to Spanish culture. By the end of the semester, students will have gained the skills to write and speak critically about film (in Spanish!), as well as a deeper understanding and appreciation of Spain’s culture, history, and cinema. Prerequisite: HISP 0730, 0740, or equivalent. Films, all written work and many readings are in Spanish. This is a writing-designated course (WRIT) so students should be prepared to craft essays through multiple drafts in workshops with their peers and consultation with the professor. -

La Comunidad De Madrid Participa En La Exposición Que Homenajea Al Cineasta Luis García Berlanga

Es una iniciativa de la Academia de Cine que se podrá visitar en la Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando hasta el 5 de septiembre La Comunidad de Madrid participa en la exposición que homenajea al cineasta Luis García Berlanga • La muestra conmemora el centenario del nacimiento del autor y podrá visitarse hasta el 5 de septiembre • Incluye fotografías, material audiovisual, guiones, carteles y planes de rodaje 9 de junio de 2021.- La Comunidad de Madrid participa en la exposición Berlanguiano. Luis García Berlanga (1921-2021), una iniciativa de la Academia de Cine que podrá visitarse en la Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando hasta el 5 de septiembre. La muestra, que cuenta con la colaboración de la Consejería de Cultura y Turismo, se suma a la celebración del centenario del nacimiento del cineasta y recopila fotografías, material audiovisual, guiones, carteles y planes de rodaje. El viceconsejero de Cultura y Turismo en funciones, Daniel Martínez, ha asistido hoy a la inauguración de esta exposición, que ha sido presidida por Sus Majestades los Reyes. Comisariada por Esperanza García Claver, la muestra analiza la evolución de la trayectoria cinematográfica de Luis García Berlanga y, en paralelo, recoge instantes de la vida española retratada por míticos fotógrafos nacionales e internacionales que la miraron e interpretaron coetáneamente. La exhibición presenta al cineasta como uno de los autores más significativos de la cultura española del siglo XX, y también expone su faceta de creador de historias y personajes inolvidables a través de sus películas. Además, analiza su presencia en la primera escuela de cine en España, donde estudió. -

La Vida Secreta De Las Palabras, Galardonada Con El XI Premio Cinematográfico José María Forqué

EGEDA BOLETIN 42-43 8/6/06 11:44 Página 1 No 42-43. 2006 Entidad autorizada por el Ministerio de Cultura para la representación, protección y defensa de los intereses de los productores audiovisuales, y de sus derechos de propiedad intelectual. (Orden de 29-10-1990 - B.O.E., 2 de Noviembre de 1990) La vida secreta de las palabras, galardonada con el XI Premio Cinematográfico José María Forqué Una historia de soledad e incomunicación, La vida secreta de las palabras, producida por El Deseo y Mediapro y dirigida por Isabel Coixet, ha sido galardonada con el Premio José María Forqué, que este año ha llegado a su undécima edición. En la gala, celebrada en el Teatro Real el 9 de mayo, La vida secreta de las palabras compartió homenaje con el documental El cielo gira, que se llevó el IV Premio Especial EGEDA, y con el productor Andrés Vicente Gómez, galardonado con la Medalla de Oro (Foto: Pipo Fernández) (Foto: de EGEDA por el conjunto de su carrera. La gala tuvo como maestros de ceremo- cida por Maestranza Films, ICAIC y Pyra- vertirán a los creadores españoles en los nias a Concha Velasco y Jorge Sanz, y con- mide Productions, y dirigida por Benito más protegidos de Europa. tó con la actuación musical del Grupo Sil- Zambrano; Obaba, producida por Oria ver Tones, que interpretó temas de rock Films, Pandora Film y Neue Impuls Film, y Por su parte, el presidente de EGEDA, En- and roll de los años 50 y 60. Esto supone dirigida por Montxo Armendáriz, y Prince- rique Cerezo, entregó la Medalla de Oro una novedad en el escenario del Teatro sas, producida por Reposado PC y Media- de la entidad al veterano productor An- Real, pues es la primera vez que acoge este pro, y dirigida por Fernando León de Ara- drés Vicente Gómez en reconocimiento “a género musical. -

Rafael Gil Y Cifesaenlace Externo, Se

Cuerpo(s) para nuestras letras: Rafael Gil y CIFESA (1940-1947) José Luis Castro de Paz Catedrático en la Universidad de Santiago de Compostela Texto publicado como introducción del libro: Rafael Gil y CIFESA, Filmoteca Española-Ministerio de Cultura, Madrid, 2007 Cuerpo(s) para nuestras letras: Rafael Gil y CIFESA (1940-1947) Para mis hijas, Beatriz y Alejandra Cuando empecé a hacer cine, pude realizar el cine con el que siempre había soñado. Leía a Galdós, a Unamuno, o a Fernández Flórez y pensaba: ‘¡Qué gran película hay aquí!’. Por eso mis primeras películas son cuentos de Fernández Flórez, de Alarcón, de Jardiel Poncela, etc. Rafael Gil 0. Introducción. Los inicios cinematográficos de Rafael Gil. La administración y el cine después de la Guerra Civil. Nacido el 22 de mayo de 1913 en el Teatro Real de Madrid, del que su padre licenciado en filosofía y letras, abogado y catedrático de latín era conservador, y acostumbrado al ambiente artístico y cultural desde muy joven, Rafael Gil estudia bachillerato en el Colegio de San José, integrado en el Instituto de San Isidro, donde desarrolla una juvenil pero ya profunda afición a la literatura y al cine. Crítico desde muy temprana edad tras serle aceptados los primeros textos que envía a la revista Gran Sport en 1930, publicará artículos sobre cinematografía y críticas de estreno tanto en periódicos (Campeón, 1933-34; La Voz 1931-32; ABC, 1932-36) como en las más importantes revistas especializadas durante la II República (Popular Films, Films Selectos, Nuestro Cinema), sin faltar tampoco asiduas colaboraciones radiofónicas y una no menos activa labor de organizador y difusor de actividades cinematográficas. -

Misoginia Y Feminismo En El Cine De Berlanga

Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando MISOGINIA Y FEMINISMO EN EL CINE DE BERLANGA Discurso de la académica electa EXCMA. SRA. D.a JOSEFINA MOLINA REIG Leído en el Acto de su Recepción Pública el día 26 de marzo de 2017 y contestación del EXCMO. SR. D. MANUEL GUTIÉRREZ ARAGÓN MADRID MMXVII [ 2 ] MISOGINIA Y FEMINISMO EN EL CINE DE BERLANGA [ 4 ] Real Academia de Bellas Artes de San Fernando MISOGINIA Y FEMINISMO EN EL CINE DE BERLANGA Discurso de la académica electa EXCMA. SRA. D.a JOSEFINA MOLINA REIG Leído en el Acto de su Recepción Pública el día 26 de marzo de 2017 y contestación del EXCMO. SR. D. MANUEL GUTIÉRREZ ARAGÓN MADRID MMXVII [ 6 ] Pintura y concreciones en población mediana, todavía. José Luis Cuerda, 2005. Discurso de la EXCMA. SRA. D.a JOSEFINA MOLINA REIG [ 8 ] Excelentísimo señor Director, señoras y señores académicos, amigas y amigos: o puedo comenzar este discurso sin agradecer a los miembros de esta Academia, excelentísimos señores Pu- Nblio López Mondéjar, José María Cruz Novillo y Ma- nuel Gutiérrez Aragón, el haberme propuesto como académica [ 9 ] de número en la Sección de Nuevas Artes de la Imagen; y a este último, especialmente, por su generosidad al querer acompañar- me hoy aquí en el uso de la palabra. Ellos me dan la ocasión de expresar ante ustedes mi admiración por el cine del maestro Berlanga, nuestro contemporáneo, que es ya figura histórica e inolvidable de la cultura española. En cuanto a mí, hoy es la primera vez en mi vida que me en- frento a un reto semejante llamando a la puerta de una Acade- mia centenaria, a cuyos componentes quizá nada nuevo les pueda descubrir sobre un cineasta de culto, que fue el primer director de cine en ingresar en ella. -

Las Mujeres Profesionales Detrás De La Cámara De

LAS MUJERES DIRECTIVAS DETRÁS DE LA CÁMARA EN LA HISTORIA DE LA TELEVISIÓN EN ESPAÑA Del nacimiento de la TV a la primera directora general de RTVE Autora: María Gallego Reguera Tutora: Asunción Bernárdez Rodal TRABAJO FIN DE MÁSTER Curso académico 2010/2011 Máster Universitario en Estudios Feministas Instituto de Investigaciones Feministas Facultad de Ciencias Económicas y Empresariales Universidad Complutense de Madrid ÍNDICE CAPÍTULO 1. INTRODUCCIÓN ......................................................................................... 2 CAPÍTULO 2. ASPECTOS TEÓRICOS Y METODOLÓGICOS ................................................ 3 2.1. Hipótesis ....................................................................................................... 3 2.2. Objetivos ...................................................................................................... 3 2.3. Metodología ................................................................................................. 4 2.4. Corpus del análisis ........................................................................................ 4 2.5. Bibliografía ................................................................................................... 4 CAPÍTULO 3. EL EMPODERAMIENTO DE LAS MUJERES PROFESIONALES DETRÁS DE LAS CÁMARAS DE TELEVISIÓN: DESDE SUS INICIOS HASTA LA PRIMERA DIRECTORA GENERAL DE RTVE ........................................................................................................... 6 3.1. CONTEXTO GENERAL ................................................................................... -

Revista ACTÚA

aisge la revista trimestral de los artistas nº 58 enero/marzo · 2019 l TONI ACOSTA l JAIME BLANCH l MARÍA ISABEL DÍAZ LAGO l MANUEL GÓMEZ PEREIRA l EVA LLORACH De teleoperadora al Goya «No es que haya hecho las cosas tarde, sino a destiempo» JUAN MARGALLO «Petra y yo hemos sido generosos, y la gente lo valora» 2 enero/marzo 2019 ÍNDICE Ned cO t Ni Os FIRMAS 04 IGNACIO MARTÍNEZ DE PISÓN ‘Un sueño infantil’ 06 ANDREA JAURRIETA ‘In her solitude’ pAnoRAMA ACTÚA 08 Manuel Gómez Pereira 38 Bando sonoro: Ciclocéano Nº 58 eNero/marzo De 2019 12 Los seis de los Goya 2019 40 El localizador: Santo Domingo (Burgos) y el documental ‘Desenterrando Sad Hill’ revista cultural de aISGe • Artistas 14 Todos los premios: Asecan, Gaudí, Mestre Intérpretes, Sociedad de Gestión 42 La peli de mi vida: Lucas Vidal Mateo, María Casares, CEC, Take, ADE, edita • Fundación AISGE Simón, Unión de Actores… y Luna Miguel Depósito legal • M-41944-2004 26 Ilustres veteranos: Micky 44 Cultura LGTBI: Antes de que ISSN • 1698-6091 28 Cosecha propia: ‘Quién puede matar nos casáramos a un niño’ 46 Esta peli no la conoces ni tú. Director de la Fundación aISGe • 32 Cien años del Metro de Madrid Empezamos por ‘El ojo de cristal’ Abel Martín Coordinador del comité editorial 48 Las restauraciones de la Filmoteca 34 Webseries: Sonia Méndez • Willy Arroyo 36 Raúl Peña, por América Latina: 50 El recuerdo de Francisco Moreno Director de aCTÚa • Fernando Neira su “lugar en el mundo” 52 Muñoz Molina y los ciclos de AISGE redacción • Héctor Álvarez J. -

Tesis Los Orígenes De La Canción Popular En El Cine Mudo

UNIVERSIDAD COMPLUTENSE DE MADRID FACULTAD DE CIENCIAS DE LA INFORMACIÓN Departamento de Comunicación Audiovisual y Publicidad I TESIS DOCTORAL Los orígenes de la canción popular en el cine mudo español, (1896-1932) MEMORIA PARA OPTAR AL GRADO DE DOCTOR PRESENTADA POR Benito Martínez Vicente Director Emilio Carlos García Fernández Madrid, 2012 © Benito Martínez Vicente, 2012 UNIVERSIDAD COMPLUTENSE DE MADRID FACULTAD DE CIENCIAS DE LA INFORMACIÓN Departamento de Comunicación Audiovisual y Publicidad I LOS ORÍGENES DE LA CANCIÓN POPULAR EN EL CINE MUDO ESPAÑOL (1896-1932) Tesis Doctoral Benito Martínez Vicente Director Dr. Emilio Carlos García Fernández Madrid, 2011 Los Orígenes de la Canción Popular en el Cine Mudo Español (1896-1932) 2 Los Orígenes de la Canción Popular en el Cine Mudo Español (1896-1932) UNIVERSIDAD COMPLUTENSE DE MADRID FACULTAD DE CIENCIAS DE LA INFORMACIÓN DEPARTAMENTO DE COMUNICACIÓN AUDIOVISUAL Y PUBLICIDAD I LOS ORÍGENES DE LA CANCIÓN POPULAR EN EL CINE MUDO ESPAÑOL (1896-1932) Tesis Doctoral Benito Martínez Vicente Director Dr. Emilio Carlos García Fernández Madrid, 2011 3 Los Orígenes de la Canción Popular en el Cine Mudo Español (1896-1932) 4 Los Orígenes de la Canción Popular en el Cine Mudo Español (1896-1932) ¡RESPETABLE PÚBLICO! Señores: no alborotéis Aunque á oscuras os quedéis, Que á oscuras no se está mal Y si esperáis hasta el final, ¡ya veréis!... 1 1 Berriatúa, Luciano. “ Los primeros años del cine en las zarzuelas ”. Lahoz Rodrigo, Juan Ignacio (coord.). A propósito de Cuesta. Escritos sobre los comienzos del cine español 1896-1920. Ediciones de la Filmoteca. Institut Valencià de l’Audiovisual i la Cinematografia Ricardo Muñoz Suay. -

Modern Humanities Research Assn a CINEMA of CONTRADICTION

ORE Open Research Exeter TITLE A Cinema of Contradiction: Picazo's "La tía Tula" (1964) and the Nuevo Cine Español AUTHORS Faulkner, Sally JOURNAL The Modern Language Review DEPOSITED IN ORE 04 November 2008 This version available at http://hdl.handle.net/10036/40237 COPYRIGHT AND REUSE Open Research Exeter makes this work available in accordance with publisher policies. A NOTE ON VERSIONS The version presented here may differ from the published version. If citing, you are advised to consult the published version for pagination, volume/issue and date of publication A CINEMA OF CONTRADICTION: PICAZO’S LA TIA‹ TULA () AND THE NUEVO CINE ESPANOL~ Even a cursory consideration of the political and industrial contexts of the Nuevo Cine Espanol~ (NCE), a movement of oppositional directors whose work was ironically funded by Franco’s government, renders apparent its contradic- tions. Caught in a double bind, these film-makers attempted to reconcile the demands of the regime with their own political beliefs. But this was not simply a case of dissident auteur battling against repressive dictatorship, for in the 1960s the Francoist government itself was struggling to marry the mutually under- mining objectives of retaining the dictatorship and at the same time opening up Spain to gradual liberalization, a process termed the apertura.Inthisarticle I argue that the tensions, or contradictions, of both the historical context of the apertura and the industrial context of the government’s promotion of a Spanish art cinema were encoded in these NCE films, and focus on one key film of the movement, Miguel Picazo’s La t‹§a Tula of 1964.