The Impact of Sound Technology on Video Game Music Composition in the 1990S

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Regulation of Ship Routes Passing Through War Zone

PUBLISHED DAZLY ander orde? of THE PRESIDENT of THE UNITED STA#TEJ by COMMITTEE on PUBLIC INFORMATION GEORGE CREEL, Chairman * * * COMPLETE Record of U. S. GOVERNMENT Activities Vot. 3 WASHINGTON, WEDNESDAY, JANUARY 22, 1919. No. 518 REGULATION OF SHIP ROUTES STATE DEPARTMENT REPORTS HOLDERS OF INSURANCE CLAIMS PASSING THROUGH WAR ZONE ON DISTURBANCES INOPORTO AGAINST ENEMY CORPORATIONS MODIFIED BY TRADE BOARD Assistant Secretary Phillips announced ARE ADVISED TO ENTER THEM to-day that the State Department advices MAY NOW PROCEED BY ANY COURSE regarding the situation in Portugal state that a movement was begun at Oporto of NOTICE BY THE ALIEN CUSTODIAN a revolutionary character designed to Vessels Bound to Certain French upset the republic in the interests of a List Given of Concerns Now in the monarchy. He said the advices were very and Other Ports, However, Re- brief, referring to the situation up to Hands of the New York Trust quired to Obtain Instructions Re- noon January 20. They did not indicate Company as Liquidator-Prompt the extent of the movement, but reported garding the Location of Mines. that everything at Lisbon was quiet. Action Is Recommended. A similar movement, he added, was The War Trade Board announces, in started about a week ago, but was sup- A. Mitehell Palmer, Alien Property a new ruling, W. T. B. R. 539, that rules pressed by the Government, which was Custodian, makes the following announce- and regulations heretofore enforced reported to have taken a number of pris- ment: -against vessels with respect to routes to oners and some of the revolutionists All persons having claiis against the be taken when proceeding through the so- were reported to have been killed in the enemy insurance companies which are called " war zone," have been modified, disturbance. -

CC-Manual.Pdf

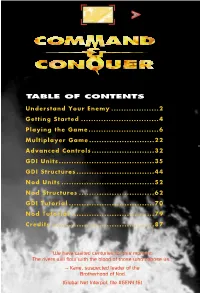

2 C&C OEM v.1 10/23/98 1:35 PM Page 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Understand Your Enemy ...................2 Getting Started ...............................4 Playing the Game............................6 Multiplayer Game..........................22 Advanced Controls.........................32 GDI Units......................................35 GDI Structures...............................44 Nod Units .....................................52 Nod Structures ..............................62 GDI Tutorial ..................................70 Nod Tutorial .................................79 Credits .........................................87 "We have waited centuries for this moment. The rivers will flow with the blood of those who oppose us." -- Kane, suspected leader of the Brotherhood of Nod (Global Net Interpol, file #GEN4:16) 2 C&C OEM v.1 10/20/98 3:19 PM Page 2 THE BROTHERHOOD OF NOD Commonly, The Brotherhood, The Ways of Nod, ShaÆSeer among the tribes of Godan; HISTORY see INTERPOL File ARK936, Aliases of the Brotherhood, for more. FOUNDED: Date unknown: exaggerated reports place the Brotherhood’s founding before 1,800 BC IDEOLOGY: To unite third-world nations under a pseudo-religious political platform with imperialist tendencies. In actuality it is an aggressive and popular neo-fascist, anti- West movement vying for total domination of the world’s peoples and resources. Operates under the popular mantra, “Brotherhood, unity, peace”. CURRENT HEAD OF STATE: Kane; also known as Caine, Jacob (INTERPOL, File TRX11-12Q); al-Quayym, Amir (MI6 DR-416.52) BASE OF OPERATIONS: Global. Command posts previously identified at Kuantan, Malaysia; somewhere in Ar-Rub’ al-Khali, Saudi Arabia; Tokyo; Caen, France. MILITARY STRENGTH: Previously believed only to be a smaller terrorist operations, a recent scandal involving United States defense contractors confirms that the Brotherhood is well-equipped and supports significant land, sea, and air military operations. -

Sanibel Island * Captiva Island * Fort Myers Coldwell Banker Residential Real Estate, Inc

We Salute Our Veterans/^ VOL. 14 NO. 18 SANIBEL & CAPTIVA ISLANDS, FLORIDA NOVEMBER 10,2006 NOVEMBER SUNRISE/SUNSET: 10 06:42 17:41 11 06:43 17:40 12 06:43 17:39 13 06:44 17:39 14 06:4517:39 15 06:45 i7\39 16 06:46 17:38 Sanibel Library To Celebrate Funding 40 Years This Sunday For Cancer Project Spurs Development * by Jim George wo years ago island resident John Kanzius, while battling a rare leu- Tkemia, had an idea for a new way to fight cancer that could revolutionize the treatment of this deadly disease. It was an idea so simple in concept - marking cancer cells and destroying them with a noninvasive radio wave cur- rents - it strained.credulity that no one had thought of it before. Two years ago it was just an idea with little prospect of funding to develop it. John Kanzius Today, it is no longer a theory. Kanzius stands on the threshold of major his technology, abstracts will be presented The Sanibel Library funding from a foreign government. at two major medical conferences over Several major cancer research centers are the next three months which prove the by Brian Johnson currently working on different elements of continued on page 16 esidents arid tourists are invited to the Sanibel Public Library on Sunday, November 12 from 3 to 5 p.m. to mark its 4Oth anniversary. Campaign To R "It's a celebration for the islanders - it is their library," said Pat Allen, who has served as executive director since 1991. -

Retro Gaming News

CONTENTS SPACE HARRIER 4 ZERO WING 30 WEWANA:PLAY APP 11 MEET THE TEAM 33 CONTACT SAM CRUISE 17 CHASE HQ 34 JASON MACKENZIE 20 MARBLE MADNESS 37 TRGN AWARD 25 MILLENNIUM 2.2 39 EMULATOR REVIEW 26 FRIDAY THE 13TH 42 MAIL BAG 29 FIST 2 48 The Retro Games News © Shinobisoft Publishing Founder Phil Wheatley Editorial: Welcome to another month of retro gaming goodness. Along with the usual classic game reviews such as Space Harrier, Contact Sam Cruise and Friday 13th, we also have a couple of unique interviews. The first of which is from a guy called Deepak Pathak who is one of the partners behind the WeWana:Play App which allows you to schedule gaming sessions with your friends. A second is with Jason ‘Kenz’ Mackenzie who is well known in the retro gaming community. We also have some new sections such as the Mail Bag and the TRGN Award. Please feel free to email your letters to the email above. Thanks as ever to everybody who contributed such as the writers, our proof reader and Logo artist. Happy Retro Gaming – Phil Wheatley © The Retro Games News Page 2 elisoftware.com © The Retro Games News Page 3 SPACE HARRIER Essentials Welcome to the fantasy zone. Get Ready! The first ever samples I heard on my Atari ST. Yet another fantastic what was the forefront hit from Sega, Space of 3D games. WOW! My friend and I Harrier came to the were in awe. arcades back in 1985. Other systems too Computers can now This game, along with were at the time talk at you as the low Sega's other popular beginning to develop quality distorted titles back then, Super 3D games Sega were sounds came at us. -

Game on Issue 72

FEATURE simple example is that at the end of a game’s section composers will usually get a chance to actually a player may have won or lost, so the music will be play the game during its formative stages, giving either triumphant or mournful, before segueing into them a feel for the music that’s required. Freelance an introduction of whatever level awaits them. It composers aren’t so lucky. Th ey get their fi rst taste becomes a complex task then to compose multiple of the action much later in the game’s build versions cues of various lengths and themes that must also and it’s sometimes just videos of gameplay provided match more than one possible visual transition. for inspiration. Which isn’t to say that freelancers are an untrustworthy mob of scoundrels. Beta versions Th en it gets harder. Games soft ware is one of very of games in their early stages of development can few formats that require simultaneously playing back involve a massive amount of data and coding. GAME ON multiple fi les without being able to employ some Th ey’re not something that can be zipped onto a kind of mixdown. A scene might need the sound fl ash drive and popped in a postbag. Mind you, of footsteps, gunshots, explosions, a voice-over and in this multi-million dollar industry security is a the music in the background – and all of these may Whether you’re wrestling a three-eyed serious issue and new soft ware is fi ercely guarded. -

NOX UK Manual 2

NOX™ PCCD MANUAL Warning: To Owners Of Projection Televisions Still pictures or images may cause permanent picture-tube damage or mark the phosphor of the CRT. Avoid repeated or extended use of video games on large-screen projection televisions. Epilepsy Warning Please Read Before Using This Game Or Allowing Your Children To Use It. Some people are susceptible to epileptic seizures or loss of consciousness when exposed to certain flashing lights or light patterns in everyday life. Such people may have a seizure while watching television images or playing certain video games. This may happen even if the person has no medical history of epilepsy or has never had any epileptic seizures. If you or anyone in your family has ever had symptoms related to epilepsy (seizures or loss of consciousness) when exposed to flashing lights, consult your doctor prior to playing. We advise that parents should monitor the use of video games by their children. If you or your child experience any of the following symptoms: dizziness, blurred vision, eye or muscle twitches, loss of consciousness, disorientation, any involuntary movement or convulsion, while playing a video game, IMMEDIATELY discontinue use and consult your doctor. Precautions To Take During Use • Do not stand too close to the screen. Sit a good distance away from the screen, as far away as the length of the cable allows. • Preferably play the game on a small screen. • Avoid playing if you are tired or have not had much sleep. • Make sure that the room in which you are playing is well lit. • Rest for at least 10 to 15 minutes per hour while playing a video game. -

Uma Perspectiva Musicológica Sobre a Formação Da Categoria Ciberpunk Na Música Para Audiovisuais – Entre 1982 E 2017

Uma perspectiva musicológica sobre a formação da categoria ciberpunk na música para audiovisuais – entre 1982 e 2017 André Filipe Cecília Malhado Dissertação de Mestrado em Ciências Musicais Área de especialização em Musicologia Histórica Setembro de 2019 I Dissertação apresentada para cumprimento dos requisitos necessários à obtenção do grau de Mestre em Ciências Musicais – Área de especialização em Musicologia Histórica, realizada sob a orientação científica da Professora Doutora Paula Gomes Ribeiro. II Às duas mulheres da minha vida que permanecem no ciberespaço do meu pensamento: Sara e Maria de Lourdes E aos dois homens da minha vida com quem conecto no meu quotidiano: Joaquim e Ricardo III Agradecimentos Mesmo tratando-se de um estudo de musicologia histórica, é preciso destacar que o meu objecto, problemática, e uma componente muito substancial do método foram direccionados para a sociologia. Por essa razão, o tema desta dissertação só foi possível porque o fenómeno social da música ciberpunk resulta do esforço colectivo dos participantes dentro da cultura, e é para eles que direciono o meu primeiro grande agradecimento. Sinto-me grato a todos os fãs do ciberpunk por manterem viva esta cultura, e por construírem à qual também pertenço, e espero, enquanto aca-fã, ter sido capaz de fazer jus à sua importância e aos discursos dos seus intervenientes. Um enorme “obrigado” à Professora Paula Gomes Ribeiro pela sua orientação, e por me ter fornecido perspectivas, ideias, conselhos, contrapontos teóricos, ajuda na resolução de contradições, e pelos seus olhos de revisora-falcão que não deixam escapar nada! Como é evidente, o seu contributo ultrapassa em muito os meandros desta investigação, pois não posso esquecer tudo aquilo que me ensinou desde o primeiro ano da Licenciatura. -

Game Scoring: Towards a Broader Theory

Western University Scholarship@Western Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository 4-16-2015 12:00 AM Game Scoring: Towards a Broader Theory Mack Enns The University of Western Ontario Supervisor Jay Hodgson The University of Western Ontario Graduate Program in Popular Music and Culture A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the equirr ements for the degree in Master of Arts © Mack Enns 2015 Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd Part of the Musicology Commons Recommended Citation Enns, Mack, "Game Scoring: Towards a Broader Theory" (2015). Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository. 2852. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/2852 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarship@Western. It has been accepted for inclusion in Electronic Thesis and Dissertation Repository by an authorized administrator of Scholarship@Western. For more information, please contact [email protected]. GAME SCORING: TOWARDS A BROADER THEORY by Mack Enns Popular Music & Culture A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts The School of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies The University of Western Ontario London, Ontario, Canada © Mack Enns 2015 Abstract “Game scoring,” that is, the act of composing music for and through gaming, is distinct from other types of scoring. To begin with, unlike other scoring activities, game scoring depends on — in fact, it arguably is — software programming. The game scorer’s choices are thus first-and-foremost limited by available gaming technology, and the “programmability” of their musical ideas given that technology, at any given historical moment. -

Roland LAPC-1 SNK Neo Geo Pocket Color Ferien Auf Monkey Island

something wonderful has happened Nr. 1/Juni 2002 interviews mit usern von damals und heute Commodore 64 1982-2002 Seite 3 charles bernstein: Play It Again, Pac-Man Teil 1 Seite 15 das vergessene betriebssystem CP/M Plus am C128 ab Seite 12 windows doch nicht ganz nutzlos: Llamasoft-Remakes am PC Seite 6/7 die rueckkehr der metagalaktischen computer steht bevor Amiga One/Commodore One [email protected] www.lotek64.com Lotek64 Juni 2002 Seite 6/7 Lotek64 2 C0MMODORE-PREISLISTE 1987 Zum 5. März 1987 hat Commodore eine neue Preisliste herausgebracht. Die aufgeführten Preise sind Listenpreise und verstehen sich in Mark inklusive Mehrwertsteuer. PC l0 II ................................................................... 2995,00 PC 20 II .................................................................. 3995,00 PC 40/AT ............................................................... 6995,00 PC 40/AT 40MB .................................................... o. A. Bürosystem S ....................................................... 4995,00 Bürosystem DL..................................................... 6495,00 Bürosystem TTX ................................................ 13695,00 MPS 2000 .............................................................. 1695,00 MPS 2000 C........................................................... 1995,00 Einzelblatt2000 ...................................................... 980,40 Traktor 2000............................................................ 437,76 Liebe Loteks! MPS 2010 ............................................................. -

Gradukarila2013.Pdf (3.769Mb)

Pulppuavan saundin kovassa ytimessä Commodore 64 -kulttuurin symbolinen rakentuminen Lemon64-internetsivuston keskusteluforumilla Walter Fabian Karila Pro gradu -tutkielma Turun yliopisto Historian, kulttuurin ja taiteiden tutkimuksen laitos Musiikkitiede Toukokuu 2013 TURUN YLIOPISTO Historian, kulttuurin ja taiteiden tutkimuksen laitos/musiikkitiede KARILA, WALTER FABIAN: Pulppuavan saundin kovassa ytimessä: Commodore 64 -kulttuurin symbolinen rakentuminen Lemon64-internetsivuston keskusteluforumilla Pro gradu -tutkielma, 81 s. Musiikkitiede Toukokuu 2013 Pro gradu -tutkielmani aihe on yhteisöllisyyden symbolinen rakentuminen Lemon64- internetsivuston keskusteluforumilla. Lemon64-internetsivusto on kohdistettu Commodore 64 -kotitietokoneesta kiinnostuneille henkilöille. Analysoin Lemon64- internetsivuston keskusteluforumin musiikkiaiheisista viestiketjuista löytyviä symboleja. Symboleja ja niiden käyttötapoja analysoimalla selvitän, miten Commodore 64 -kulttuurissa syntyy yhteisöllisyyttä. Analyysissäni sovellan verkkoyhteisöjen tutkimusta ja sosiologista teoriaa yhteisöjen symbolisesta rakentumisesta. Teoreettisen viitekehykseni mukaan yhteisöt rakentuvat yhteisön jäsenten käyttämien symbolien avulla. Tutkielmassa analysoin sanoista muodostettuja symboleja. Pohjustan aihettani käymällä läpi Commodore 64 -kotitietokoneen tuotannollisia taustoja. Selvitän myös 1980- ja 1990-lukujen tietokonealakulttuurien merkitystä Commodore 64 -kulttuurin kehitykselle. Analyysini tuo esiin Commodore 64 -kulttuurin ominaispiirteet sekä tietokonealakulttuurina -

FREEZE! Issue #00 FREEZE the ULTIMATE GAMING & CHEAT FANZINE for YOUR COMMODORE 64

FREEZE! Issue #00 FREEZE THE ULTIMATE GAMING & CHEAT FANZINE FOR YOUR COMMODORE 64 FULLY COMPATIBLE WITH KEYSTONE KAPERS EXCLUSIVE POKES ‘N’ CODES RATSPLAT IS PLUCKED FROM THE MOULDY CUPBOARD ISSUE #32 JULIAN RIGNALL ZZAPS BACK TO MAY 1986 CORONA FREE WE DON’T DO REVIEWS! W.T.F. FROM TFW8B.COM HARDWARE REVIEW OF THE TAPUINO1 LOADING DEVICE £3.99 FREEZE! Issue #00 LOAD “ISSUE 32”,8,1 LOADING... TEXT 02 | LOAD “ISSUE 32”,8,1 NUMBER # To Bombay, a traveling circus came... # CRUNCHING 03 | FOUND ISSUE 32 IN THIS ISSUE: Did you find FREEZE64... or did it find YOU! :-o 04 | COVER FEATURE: CJ’S ELEPHANT ANTICS 17 As C64 platform games go, CJ’s Elephant Antics is right up there with the best RATS TO of them, and so we thought it was time to share some elephant love. SPLAT! 08 | OUT OF THE ‘MOULDY CUPBOARD’ 2 The Mouldy Cupboard is full of RATS! Time to SPLAT them! EXTENDED 10 | DIARY OF A GAME – THE MAKING OF BADLANDS INTERVIEWS We’re about half way through Steve’s fab diary of a game, and there’s a lot more juicy information to share with you about the making of Badlands. 51 12 | BITS ‘N’ BYTES ELEPHANTS We share some news of a delightful Commodore 64 game in the making. 42 13 | JULIAN RIGNALL’S ZZAPBACK! The fab Julian Rignall celebrates SIZZLERS from ZZAP!64 issue 13 – May 1986. SCREENSHOTS 16 | SECRET SQUIRREL INVESTIGATES 13,258 Our bushy-tailed friend shares a few secrets about Kentilla and LA Police Dept. -

Timbaland Plagiarism Controversy

EN | FR Timbaland plagiarism controversy From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Timbaland's plagiarism controversy occurred in January 2007, when several news sources reported that Timbaland (Timothy Z. Mosley) was alleged to have plagiarized several elements (both motifs and samples) in the song "Do It" on the 2006 album Loose by Nelly Furtado without giving credit or compensation.[1][2][3] The song itself was released as the fifth North American single from Loose on July 24, 2007. Background The original track, entitled "Acidjazzed Evening", is a chiptune-style 4-channel Amiga module composed by Finnish demoscener Janne Suni (a.k.a. Tempest).[4] The song won first place in the Oldskool Music competition at Assembly 2000, a demoparty held in Helsinki, Finland in 2000.[5] According to Scene.org, the song was uploaded to their servers the same year, long before the release of the song by Furtado. The song was later remixed (with Suni's permission) by Norwegian Glenn Rune Gallefoss (a.k.a. GRG) for the Commodore 64 in SID format - this is the version which was later allegedly sampled for "Do It". It was added to the High Voltage SID Collection on December 21, 2002.[6] A video which claims to show proof of the theft was posted to YouTube on January 12, 2007.[7] Another video was posted to YouTube on January 14, 2007, claiming Timbaland also stole the tune a year earlier for the ringtone Block Party, one of several that were sold in the United States in 2005.[8] Authors' comments Janne Suni Janne Suni posted the following comment regarding the copyright status of "Acidjazzed Evening" on January 15, 2007: "...I have never given up the copyrights of Acidjazzed Evening.