Command and Conquer in the Development of Real-Time Strategy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Prophecy: the Fall of Trinadon in This Quest You Take the Part Comfortable Village Is Overrun En Dungeon Levels

t Vol. VI, # 6 June, 1989 $2.50 Best Quest of the Month Prophecy: The Fall of Trinadon In this quest you take the part comfortable village is overrun en dungeon levels. I was par- games with pretty impressive of a lowly marketing execu- by empire soldiers. ticularly pleased to find that weapons lists, but I do know tive from the Sony corpora- Alas, while dreaming you could move back and that Prophecy has some of the tion. Your career depends on about these events, you awak- forth between most original discovering why the compa- en to the screams of your several of the items I've seen ny's share in the television family and friends as they are dungeons, in a long time. market has dropped since Syl- ruthlessly butchered by em- which is Besides the tra- vania released the black ma- pire troops. Quickly you don handy if you ditional array of trix picture tube. What's that? gloves and shield. You are realize you've swords, knifes, Oh, that's Trinitron ... wrong unarmed but determined, one reached one axes and bows quest-this is the one about way or another, to obliterate level without of varying lev- Trinadon. the threat of Kre11ane in re- obtaining a els, there are The central character in turn for the slaughter of your necessary item also items that Trinadon is practically the father. Your adventure has from another are not so obvi- only person without a name, begun! one. ous, such as simple blue pow- so I'll just call him Steve. -

Strategy Games Big Huge Games • Bruce C

04 3677_CH03 6/3/03 12:30 PM Page 67 Chapter 3 THE EXPERTS • Sid Meier, Firaxis General Game Design: • Bill Roper, Blizzard North • Brian Reynolds, Strategy Games Big Huge Games • Bruce C. Shelley, Ensemble Studios • Peter Molyneux, Do you like to use some brains along with (or instead of) brawn Lionhead Studios when gaming? This chapter is for you—how to create breathtaking • Alex Garden, strategy games. And do we have a roundtable of celebrities for you! Relic Entertainment Sid Meier, Firaxis • Louis Castle, There’s a very good reason why Sid Meier is one of the most Electronic Arts/ accomplished and respected game designers in the business. He Westwood Studios pioneered the industry with a number of unprecedented instant • Chris Sawyer, Freelance classics, such as the very first combat flight simulator, F-15 Strike Eagle; then Pirates, Railroad Tycoon, and of course, a game often • Rick Goodman, voted the number one game of all time, Civilization. Meier has con- Stainless Steel Studios tributed to a number of chapters in this book, but here he offers a • Phil Steinmeyer, few words on game inspiration. PopTop Software “Find something you as a designer are excited about,” begins • Ed Del Castillo, Meier. “If not, it will likely show through your work.” Meier also Liquid Entertainment reminds designers that this is a project that they’ll be working on for about two years, and designers have to ask themselves whether this is something they want to work on every day for that length of time. From a practical point of view, Meier says, “You probably don’t want to get into a genre that’s overly exhausted.” For me, working on SimGolf is a fine example, and Gettysburg is another—something I’ve been fascinated with all my life, and it wasn’t mainstream, but was a lot of fun to write—a fun game to put together. -

Uva-DARE (Digital Academic Repository)

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) Engineering emergence: applied theory for game design Dormans, J. Publication date 2012 Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Dormans, J. (2012). Engineering emergence: applied theory for game design. Creative Commons. General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:26 Sep 2021 Ludography Agricola (2007, board game). Lookout Games, Uwe Rosenberg. Americas Army (2002, PC). U.S. Army. Angry Birds (2009, iOS, Android, others). Rovio Mobile Ltd. Ascent (2009, PC). J. Dormans. Assassins Creed (2007, PS3, Xbox 360). Ubisoft, Inc., Ubisoft Divertissements Inc. Baldurs Gate (1998, PC). Interplay Productions, Inc. BioWare Corporations. Bejeweled (2000, PC). PopCap Games, Inc. Bewbees (2011, Android, iOS). GewGawGames. Blood Bowl, third edition (1994, board game). -

Mythology Teachers' Guide

Teachers’ Guide Mythology: The Gods, Heroes, and Monsters of Ancient Greece by Lady Hestia Evans • edited by Dugald A. Steer • illustrated by Nick Harris, Nicki Palin, and David Wyatt • decorative friezes by Helen Ward Age 8 and up • Grade 3 and up ISBN: 978-0-7636-3403-2 $19.99 ($25.00 CAN) ABOUT THE BOOK Mythology purports to be an early nineteenth-century primer on Greek myths written by Lady Hestia Evans. This particular edition is inscribed to Lady Hestia’s friend John Oro, who was embarking on a tour of the sites of ancient Greece. Along his journey, Oro has added his own notes, comments, and drawings in the margins — including mention of his growing obsession with the story of King Midas and a visit to Olympus to make a daring request of Zeus himself. This guide to Mythology is designed to support a creative curriculum and provide opportunities to make links across subjects. The suggested activities help students make connections with and build on their existing knowledge, which may draw from film, computer games, and other popular media as well as books and more traditional sources. We hope that the menu of possibilities presented here will serve as a creative springboard and inspiration for you in your classroom. For your ease of use, the guide is structured to follow the book in a chapter-by-chapter order. However, many of the activities allow teachers to draw on material from several chapters. For instance, the storytelling performance activity outlined in the section “An Introduction to Mythology” could also be used with stories from other chapters. -

Master List of Games This Is a List of Every Game on a Fully Loaded SKG Retro Box, and Which System(S) They Appear On

Master List of Games This is a list of every game on a fully loaded SKG Retro Box, and which system(s) they appear on. Keep in mind that the same game on different systems may be vastly different in graphics and game play. In rare cases, such as Aladdin for the Sega Genesis and Super Nintendo, it may be a completely different game. System Abbreviations: • GB = Game Boy • GBC = Game Boy Color • GBA = Game Boy Advance • GG = Sega Game Gear • N64 = Nintendo 64 • NES = Nintendo Entertainment System • SMS = Sega Master System • SNES = Super Nintendo • TG16 = TurboGrafx16 1. '88 Games (Arcade) 2. 007: Everything or Nothing (GBA) 3. 007: NightFire (GBA) 4. 007: The World Is Not Enough (N64, GBC) 5. 10 Pin Bowling (GBC) 6. 10-Yard Fight (NES) 7. 102 Dalmatians - Puppies to the Rescue (GBC) 8. 1080° Snowboarding (N64) 9. 1941: Counter Attack (TG16, Arcade) 10. 1942 (NES, Arcade, GBC) 11. 1942 (Revision B) (Arcade) 12. 1943 Kai: Midway Kaisen (Japan) (Arcade) 13. 1943: Kai (TG16) 14. 1943: The Battle of Midway (NES, Arcade) 15. 1944: The Loop Master (Arcade) 16. 1999: Hore, Mitakotoka! Seikimatsu (NES) 17. 19XX: The War Against Destiny (Arcade) 18. 2 on 2 Open Ice Challenge (Arcade) 19. 2010: The Graphic Action Game (Colecovision) 20. 2020 Super Baseball (SNES, Arcade) 21. 21-Emon (TG16) 22. 3 Choume no Tama: Tama and Friends: 3 Choume Obake Panic!! (GB) 23. 3 Count Bout (Arcade) 24. 3 Ninjas Kick Back (SNES, Genesis, Sega CD) 25. 3-D Tic-Tac-Toe (Atari 2600) 26. 3-D Ultra Pinball: Thrillride (GBC) 27. -

THE PRIMORDIAL ECONOMICS of CHEATING: Trading Skill for Glory Or Vital Steps to Evolved Play?

THE PRIMORDIAL ECONOMICS OF CHEATING: Trading Skill for Glory or Vital Steps to Evolved Play? Robert MacBride Games Programs, RMIT University, Melbourne, VIC 3000 Australia (+61 3) 9925-2000 [email protected] [email protected] ABSTRACT firstly outline some of the ways in which ethics have been In a period marked by cultural, industrial and technological conceptualised in game play, following this; a look at a case convergences of new media platforms globally, what study of Melbourne MMO players and their definitions of constitutes ‘Situated play’? One of the key aspects of the the “ethics” in games through the rubric of cheating. global digital industries has been the increasing importance of locality in determining modes of game play. Far from The case study of MMO users in Melbourne will consist of homogenising game play, globalisation has resulted in users from over 10 ethnic backgrounds. The sample study “disjuncture” and “difference” at the level of the local. Take, will ask users about their definition of cheating and right or for example, the considerable successes of the Massively wrong game play so that we may mediate on some of Multiplayer Online scene; despite its movement towards the saliencies and nascent socio-cultural dimensions of play and idea of the connected gaming civilisation model, many locality. MMO are not global but, rather, played by certain communities that share linguistic, socio-cultural or political economy similarities. A considerably poignant example KEYWORDS would be the way in which different aesthetics appeal to Cheat, Debug, Trainer, Twinking, Build & Levelling guides, cultural contexts. The formulation of these distinctive taste Camping, Programming flaw exploitation, Walkthrough, cultures are marked by what Pierre Bourdieu noted as FAQ (Frequently asked question document), Patching, modes of cultural (productions of knowledges), social and Speed run, Gold/Stat farming, Ghosting, Unlockable, Easter economic capital. -

A History of Real-Time Strategy Gameplay from Decryption to Prediction: Introducing the Actional Statement

A History of Real-Time Strategy Gameplay From Decryption to Prediction: Introducing the Actional Statement Simon Dor Université de Montréal It is quite usual in strategy games to claim that strategies have a history of their own, chess being the canonical example (Murray 2002). The common strategies of a certain game change over time—often called the “metagame”— and can be retraced from a historical perspective. StarCraft II’s (Blizzard Entertainment, 2010-) community goes as far as to write histories of specific matchups (Alejandrisha et al. 2012), but every strategy game in some regards opens a space where gameplay can evolve. A 2009 walkthrough of the 1994 game Warcraft: Orcs and Humans (Blizzard Entertainment) states that the “reason most people think this game is so hard, is because they try to play it like an RTS [Real-Time Strategy game]” (Boehmer 2009, §2.03). It is quite surprising today to read this claim, considering Warcraft is widely regarded as one of the pioneers in the RTS genre, alongside with its Westwood’s earlier counterpart, Dune II: The Building of A Dynasty (Westwood Studios, 1992). In the perspective of mapping a history of the RTS genre, this kind of statement is quite problematic. Playing a RTS in 2009 is not like what was playing a strategy game in 1994, but how can we as researchers take into account a historical distance in playing habits? Warcraft’s difficulty was probably raised retrospectively, since playing habits acquired in subsequent games induce certain types of actions that do not necessarily favor victory in earlier releases. -

Regulation of Ship Routes Passing Through War Zone

PUBLISHED DAZLY ander orde? of THE PRESIDENT of THE UNITED STA#TEJ by COMMITTEE on PUBLIC INFORMATION GEORGE CREEL, Chairman * * * COMPLETE Record of U. S. GOVERNMENT Activities Vot. 3 WASHINGTON, WEDNESDAY, JANUARY 22, 1919. No. 518 REGULATION OF SHIP ROUTES STATE DEPARTMENT REPORTS HOLDERS OF INSURANCE CLAIMS PASSING THROUGH WAR ZONE ON DISTURBANCES INOPORTO AGAINST ENEMY CORPORATIONS MODIFIED BY TRADE BOARD Assistant Secretary Phillips announced ARE ADVISED TO ENTER THEM to-day that the State Department advices MAY NOW PROCEED BY ANY COURSE regarding the situation in Portugal state that a movement was begun at Oporto of NOTICE BY THE ALIEN CUSTODIAN a revolutionary character designed to Vessels Bound to Certain French upset the republic in the interests of a List Given of Concerns Now in the monarchy. He said the advices were very and Other Ports, However, Re- brief, referring to the situation up to Hands of the New York Trust quired to Obtain Instructions Re- noon January 20. They did not indicate Company as Liquidator-Prompt the extent of the movement, but reported garding the Location of Mines. that everything at Lisbon was quiet. Action Is Recommended. A similar movement, he added, was The War Trade Board announces, in started about a week ago, but was sup- A. Mitehell Palmer, Alien Property a new ruling, W. T. B. R. 539, that rules pressed by the Government, which was Custodian, makes the following announce- and regulations heretofore enforced reported to have taken a number of pris- ment: -against vessels with respect to routes to oners and some of the revolutionists All persons having claiis against the be taken when proceeding through the so- were reported to have been killed in the enemy insurance companies which are called " war zone," have been modified, disturbance. -

Peder Larson

Command and Conquer by Peder Larson Professor Henry Lowood STS 145 March 18, 2002 Introduction It was impossible to be a computer gamer in the mid-1990s and not be aware of Command and Conquer. During 1995 and the following couple years, Command and Conquer mania was at its peak, and the game spawned a whole series that sold over 15 million copies worldwide, making it "The best selling Computer Strategy Game Series of All Time" (Westwood Studios). Sales reached $450 million before Command and Conquer: Tiberian Sun, the third major title in the series, was released in 1999 (Romaine). The game introduced many to the genre of real-time strategy (RTS) games, in which Starcraft, Warcraft, Age of Empires, and Total Annihilation all fall. Command and Conquer, however, was extremely similar to Dune 2, a 1992 release by Westwood Studios. The interface, controls, and "harvest, build, and destroy" style were all borrowed, with some minor improvements. Yet Command and Conquer was much more successful. The graphics were better and the plot was new, but the most important improvement was the integration of network play. This greatly increased the time spent playing the game and built up a community surrounding the game. These multiplayer capabilities made Command and Conquer different and more successful than previous RTS games. History In 1983, there was only one store in Las Vegas that sold Apple hardware and software in Las Vegas: Century 23. Louis Castle had just finished up majoring in fine arts and computer science at University of Nevada - Las Vegas and was working there as a salesman. -

CC-Manual.Pdf

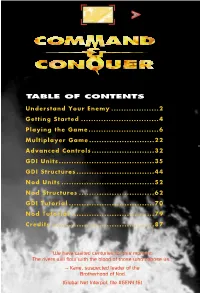

2 C&C OEM v.1 10/23/98 1:35 PM Page 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Understand Your Enemy ...................2 Getting Started ...............................4 Playing the Game............................6 Multiplayer Game..........................22 Advanced Controls.........................32 GDI Units......................................35 GDI Structures...............................44 Nod Units .....................................52 Nod Structures ..............................62 GDI Tutorial ..................................70 Nod Tutorial .................................79 Credits .........................................87 "We have waited centuries for this moment. The rivers will flow with the blood of those who oppose us." -- Kane, suspected leader of the Brotherhood of Nod (Global Net Interpol, file #GEN4:16) 2 C&C OEM v.1 10/20/98 3:19 PM Page 2 THE BROTHERHOOD OF NOD Commonly, The Brotherhood, The Ways of Nod, ShaÆSeer among the tribes of Godan; HISTORY see INTERPOL File ARK936, Aliases of the Brotherhood, for more. FOUNDED: Date unknown: exaggerated reports place the Brotherhood’s founding before 1,800 BC IDEOLOGY: To unite third-world nations under a pseudo-religious political platform with imperialist tendencies. In actuality it is an aggressive and popular neo-fascist, anti- West movement vying for total domination of the world’s peoples and resources. Operates under the popular mantra, “Brotherhood, unity, peace”. CURRENT HEAD OF STATE: Kane; also known as Caine, Jacob (INTERPOL, File TRX11-12Q); al-Quayym, Amir (MI6 DR-416.52) BASE OF OPERATIONS: Global. Command posts previously identified at Kuantan, Malaysia; somewhere in Ar-Rub’ al-Khali, Saudi Arabia; Tokyo; Caen, France. MILITARY STRENGTH: Previously believed only to be a smaller terrorist operations, a recent scandal involving United States defense contractors confirms that the Brotherhood is well-equipped and supports significant land, sea, and air military operations. -

Sanibel Island * Captiva Island * Fort Myers Coldwell Banker Residential Real Estate, Inc

We Salute Our Veterans/^ VOL. 14 NO. 18 SANIBEL & CAPTIVA ISLANDS, FLORIDA NOVEMBER 10,2006 NOVEMBER SUNRISE/SUNSET: 10 06:42 17:41 11 06:43 17:40 12 06:43 17:39 13 06:44 17:39 14 06:4517:39 15 06:45 i7\39 16 06:46 17:38 Sanibel Library To Celebrate Funding 40 Years This Sunday For Cancer Project Spurs Development * by Jim George wo years ago island resident John Kanzius, while battling a rare leu- Tkemia, had an idea for a new way to fight cancer that could revolutionize the treatment of this deadly disease. It was an idea so simple in concept - marking cancer cells and destroying them with a noninvasive radio wave cur- rents - it strained.credulity that no one had thought of it before. Two years ago it was just an idea with little prospect of funding to develop it. John Kanzius Today, it is no longer a theory. Kanzius stands on the threshold of major his technology, abstracts will be presented The Sanibel Library funding from a foreign government. at two major medical conferences over Several major cancer research centers are the next three months which prove the by Brian Johnson currently working on different elements of continued on page 16 esidents arid tourists are invited to the Sanibel Public Library on Sunday, November 12 from 3 to 5 p.m. to mark its 4Oth anniversary. Campaign To R "It's a celebration for the islanders - it is their library," said Pat Allen, who has served as executive director since 1991. -

Disparo En Red 05 Disparo En Red

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Digital Collection - Science Fiction & Fantasy Digital Collection - Science Fiction & Fantasy Publications 1-9-2005 Disparo en Red 05 Disparo En Red Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/scifistud_pub Part of the Fiction Commons Scholar Commons Citation Disparo En Red, "Disparo en Red 05 " (2005). Digital Collection - Science Fiction & Fantasy Publications. Paper 179. http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/scifistud_pub/179 This Journal is brought to you for free and open access by the Digital Collection - Science Fiction & Fantasy at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Digital Collection - Science Fiction & Fantasy Publications by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. HOY: 9 de ENERO del 2005 DISPARO EN RED: Boletín electrónico de ciencia-ficción y fantasía. De frecuencia quincenal y totalmente gratis. Editores: darthmota Jartower Colaboradores: Taller de Creación ESPIRAL de ciencia ficción y fantasía. Anabel Enriquez Piñeiro Juan Pablo Noroña. Jorge Enrique Lage. 0. CONTENIDOS: 1.La frase de hoy: J.R.R. Tolkien. 2.Artículo: Anteproyecto para un canon de la CF, César Mallorquí. 3.Cuento clásico: La Puerta del Laberinto, Michael Ende. 4.Cuento made in Cuba: Los que van a morir, Erick Mota. 5.Curiosidades. Consejos de Bruce Sterling. 6.Reseñas. Dune, observaciones sobre la obra de Frank Herbert, por Yeray Rodríguez Domínguez. 7.¿Cómo contactarnos? 1. LA FRASE DE HOY: Supongo que soy un reaccionario. El mainstream de la literatura contemporánea es muy aburrido, ¿no es verdad? Yo estoy ofreciendo un saludable cambio de dieta. J.R.R.