The Functions of Music in Interactive Media

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Einfluss Technischer Mittel Auf Die Kompostionsmethoden Von Jeremy Soule

Einfluss technischer Mittel auf die Kom- positionsmethoden von Jeremy Soule Andrea Giffinger Institut für Musikwissenschaft, Innsbruck Zusammenfassung Im folgenden Text werden einige der Kompositionsmethoden Jeremy Soules exemplarisch herausge- hoben. Es sollen dabei die verschiedenen Parameter aufgezeigt werden, die den kreativen Prozess eines Komponisten beeinflussen. Darüber hinaus wird auch auf einige der Probleme, mit denen er aufgrund der ihm zur Verfügung stehenden technischen Mittel konfrontiert wurde, eingegangen, sowie deren Lösung gezeigt. Am Ende werden Forschungsfragen im Bezug auf die Elder Scrolls Reihe gestellt. 1 Einleitung Computerspiele wurden bereits in den 1970er kommerziell vermarktet, die akademische For- schung allerdings beschäftigte sich erst in den späten 1990er eingehender mit diesem Medien- phänomen. Seitdem haben sich verschiedenste Disziplinen, die gemeinsam das Forschungsfeld der Video Game Studies bilden, auf analytischer Ebene mit Computerspielen auseinandergesetzt (Süß, 2006). Um die Musik in Computerspielen zu untersuchen, werden nicht selten Methoden der Analyse von Filmmusik angewandt. Jedoch bergen diese Gefahren, da es sich, im Gegen- satz zum Film, um ein interaktives Medium handelt. Je nach Genre bestimmt der Spieler den Ablauf der Musik, wobei ihre Wirkung wiederum Auswirkungen auf den Ablauf des Spiels ha- ben kann. Gerade in der Spielreihe Elder Scrolls III-V, deren von Jeremy Soule komponierte Musik Gegenstand meiner Forschung ist, erhält diese durch die offene Spielwelt einen perfor- mativen Aspekt. Die spärlich vorhandene Literatur über Musik in Computerspielen, der Mangel an geeigneten Analyse Theorien und die Tatsache, dass sie immer präsenter in den Konzertsälen wird, ist Anreiz sich mit diesem Thema intensiv zu beschäftigen. 2 Umgang mit technischen Mitteln Soule komponiert seit 1995 Musik für Computerspiele (Dean, 2013) wie Secret of Evermo- re Total Annihilation, Star Wars: Knights of the Old Republic, die Harry Potter Reihe, Guild VeröffentlichtPlatzhalter für durch DOI die und Gesellschaft ggf. -

Regulation of Ship Routes Passing Through War Zone

PUBLISHED DAZLY ander orde? of THE PRESIDENT of THE UNITED STA#TEJ by COMMITTEE on PUBLIC INFORMATION GEORGE CREEL, Chairman * * * COMPLETE Record of U. S. GOVERNMENT Activities Vot. 3 WASHINGTON, WEDNESDAY, JANUARY 22, 1919. No. 518 REGULATION OF SHIP ROUTES STATE DEPARTMENT REPORTS HOLDERS OF INSURANCE CLAIMS PASSING THROUGH WAR ZONE ON DISTURBANCES INOPORTO AGAINST ENEMY CORPORATIONS MODIFIED BY TRADE BOARD Assistant Secretary Phillips announced ARE ADVISED TO ENTER THEM to-day that the State Department advices MAY NOW PROCEED BY ANY COURSE regarding the situation in Portugal state that a movement was begun at Oporto of NOTICE BY THE ALIEN CUSTODIAN a revolutionary character designed to Vessels Bound to Certain French upset the republic in the interests of a List Given of Concerns Now in the monarchy. He said the advices were very and Other Ports, However, Re- brief, referring to the situation up to Hands of the New York Trust quired to Obtain Instructions Re- noon January 20. They did not indicate Company as Liquidator-Prompt the extent of the movement, but reported garding the Location of Mines. that everything at Lisbon was quiet. Action Is Recommended. A similar movement, he added, was The War Trade Board announces, in started about a week ago, but was sup- A. Mitehell Palmer, Alien Property a new ruling, W. T. B. R. 539, that rules pressed by the Government, which was Custodian, makes the following announce- and regulations heretofore enforced reported to have taken a number of pris- ment: -against vessels with respect to routes to oners and some of the revolutionists All persons having claiis against the be taken when proceeding through the so- were reported to have been killed in the enemy insurance companies which are called " war zone," have been modified, disturbance. -

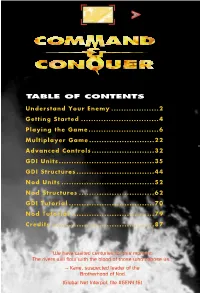

CC-Manual.Pdf

2 C&C OEM v.1 10/23/98 1:35 PM Page 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Understand Your Enemy ...................2 Getting Started ...............................4 Playing the Game............................6 Multiplayer Game..........................22 Advanced Controls.........................32 GDI Units......................................35 GDI Structures...............................44 Nod Units .....................................52 Nod Structures ..............................62 GDI Tutorial ..................................70 Nod Tutorial .................................79 Credits .........................................87 "We have waited centuries for this moment. The rivers will flow with the blood of those who oppose us." -- Kane, suspected leader of the Brotherhood of Nod (Global Net Interpol, file #GEN4:16) 2 C&C OEM v.1 10/20/98 3:19 PM Page 2 THE BROTHERHOOD OF NOD Commonly, The Brotherhood, The Ways of Nod, ShaÆSeer among the tribes of Godan; HISTORY see INTERPOL File ARK936, Aliases of the Brotherhood, for more. FOUNDED: Date unknown: exaggerated reports place the Brotherhood’s founding before 1,800 BC IDEOLOGY: To unite third-world nations under a pseudo-religious political platform with imperialist tendencies. In actuality it is an aggressive and popular neo-fascist, anti- West movement vying for total domination of the world’s peoples and resources. Operates under the popular mantra, “Brotherhood, unity, peace”. CURRENT HEAD OF STATE: Kane; also known as Caine, Jacob (INTERPOL, File TRX11-12Q); al-Quayym, Amir (MI6 DR-416.52) BASE OF OPERATIONS: Global. Command posts previously identified at Kuantan, Malaysia; somewhere in Ar-Rub’ al-Khali, Saudi Arabia; Tokyo; Caen, France. MILITARY STRENGTH: Previously believed only to be a smaller terrorist operations, a recent scandal involving United States defense contractors confirms that the Brotherhood is well-equipped and supports significant land, sea, and air military operations. -

Sanibel Island * Captiva Island * Fort Myers Coldwell Banker Residential Real Estate, Inc

We Salute Our Veterans/^ VOL. 14 NO. 18 SANIBEL & CAPTIVA ISLANDS, FLORIDA NOVEMBER 10,2006 NOVEMBER SUNRISE/SUNSET: 10 06:42 17:41 11 06:43 17:40 12 06:43 17:39 13 06:44 17:39 14 06:4517:39 15 06:45 i7\39 16 06:46 17:38 Sanibel Library To Celebrate Funding 40 Years This Sunday For Cancer Project Spurs Development * by Jim George wo years ago island resident John Kanzius, while battling a rare leu- Tkemia, had an idea for a new way to fight cancer that could revolutionize the treatment of this deadly disease. It was an idea so simple in concept - marking cancer cells and destroying them with a noninvasive radio wave cur- rents - it strained.credulity that no one had thought of it before. Two years ago it was just an idea with little prospect of funding to develop it. John Kanzius Today, it is no longer a theory. Kanzius stands on the threshold of major his technology, abstracts will be presented The Sanibel Library funding from a foreign government. at two major medical conferences over Several major cancer research centers are the next three months which prove the by Brian Johnson currently working on different elements of continued on page 16 esidents arid tourists are invited to the Sanibel Public Library on Sunday, November 12 from 3 to 5 p.m. to mark its 4Oth anniversary. Campaign To R "It's a celebration for the islanders - it is their library," said Pat Allen, who has served as executive director since 1991. -

Game on Issue 72

FEATURE simple example is that at the end of a game’s section composers will usually get a chance to actually a player may have won or lost, so the music will be play the game during its formative stages, giving either triumphant or mournful, before segueing into them a feel for the music that’s required. Freelance an introduction of whatever level awaits them. It composers aren’t so lucky. Th ey get their fi rst taste becomes a complex task then to compose multiple of the action much later in the game’s build versions cues of various lengths and themes that must also and it’s sometimes just videos of gameplay provided match more than one possible visual transition. for inspiration. Which isn’t to say that freelancers are an untrustworthy mob of scoundrels. Beta versions Th en it gets harder. Games soft ware is one of very of games in their early stages of development can few formats that require simultaneously playing back involve a massive amount of data and coding. GAME ON multiple fi les without being able to employ some Th ey’re not something that can be zipped onto a kind of mixdown. A scene might need the sound fl ash drive and popped in a postbag. Mind you, of footsteps, gunshots, explosions, a voice-over and in this multi-million dollar industry security is a the music in the background – and all of these may Whether you’re wrestling a three-eyed serious issue and new soft ware is fi ercely guarded. -

A Composers Guide to Game Music Pdf Free Download

A COMPOSERS GUIDE TO GAME MUSIC PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Winifred Phillips | 288 pages | 11 Aug 2017 | MIT Press Ltd | 9780262534499 | English | Cambridge, United States A Composers Guide to Game Music PDF Book The challenges unique to game composers are discussed at length. Video Games. Either we turn down the gig or set aside our emotions and listen for some musical element in that genre that tickles our interest. Music in video games is often a sophisticated, complex composition that serves to engage the player, set the pace of play, and aid interactivity. It really is intended for composers. Recommended: Ear Training Games. Each layer needs to have its moments to shine, but not at the expense of the others. Aspiring composers should have a burning desire to contribute their own ideas to the larger musical conversation. Phillips offers detailed coverage of essential topics, including musicianship and composition experience; immersion; musical themes; music and game genres; workflow; working with a development team; linear music; interactive music, both rendered and generative; audio technology, from mixers and preamps to software; and running a business. July 2, He also wangles in some light electronics for many of his compositions, so expect to hear something slightly different every time. This book offers guidance to composers who are interested in writing music for video games. But in a video game the length of each scene or level can vary greatly. Outside of the theories and techniques for creating this music, there is also a wealth of information on how to function within a development team and how to meet the expectations of the job. -

NOX UK Manual 2

NOX™ PCCD MANUAL Warning: To Owners Of Projection Televisions Still pictures or images may cause permanent picture-tube damage or mark the phosphor of the CRT. Avoid repeated or extended use of video games on large-screen projection televisions. Epilepsy Warning Please Read Before Using This Game Or Allowing Your Children To Use It. Some people are susceptible to epileptic seizures or loss of consciousness when exposed to certain flashing lights or light patterns in everyday life. Such people may have a seizure while watching television images or playing certain video games. This may happen even if the person has no medical history of epilepsy or has never had any epileptic seizures. If you or anyone in your family has ever had symptoms related to epilepsy (seizures or loss of consciousness) when exposed to flashing lights, consult your doctor prior to playing. We advise that parents should monitor the use of video games by their children. If you or your child experience any of the following symptoms: dizziness, blurred vision, eye or muscle twitches, loss of consciousness, disorientation, any involuntary movement or convulsion, while playing a video game, IMMEDIATELY discontinue use and consult your doctor. Precautions To Take During Use • Do not stand too close to the screen. Sit a good distance away from the screen, as far away as the length of the cable allows. • Preferably play the game on a small screen. • Avoid playing if you are tired or have not had much sleep. • Make sure that the room in which you are playing is well lit. • Rest for at least 10 to 15 minutes per hour while playing a video game. -

10Th IAA FINALISTS ANNOUNCED

10th Annual Interactive Achievement Awards Finalists GAME TITLE PUBLISHER DEVELOPER CREDITS Outstanding Achievement in Animation ANIMATION DIRECTOR LEAD ANIMATOR Gears of War Microsoft Game Studios Epic Games Aaron Herzog & Jay Hosfelt Jerry O'Flaherty Daxter Sony Computer Entertainment ReadyatDawn Art Director: Ru Weerasuriya Jerome de Menou Lego Star Wars II: The Original Trilogy LucasArts Traveller's Tales Jeremy Pardon Jeremy Pardon Rayman Raving Rabbids Ubisoft Ubisoft Montpellier Patrick Bodard Patrick Bodard Fight Night Round 3 Electronic Arts EA Sports Alan Cruz Andy Konieczny Outstanding Achievement in Art Direction VISUAL ART DIRECTOR TECHNICAL ART DIRECTOR Gears of War Microsoft Game Studios Epic Games Jerry O'Flaherty Chris Perna Final Fantasy XII Square Enix Square Enix Akihiko Yoshida Hideo Minaba Call of Duty 3 Activison Treyarch Treyarch Treyarch Tom Clancy's Rainbow Six: Vegas Ubisoft Ubisoft Montreal Olivier Leonardi Jeffrey Giles Viva Piñata Microsoft Game Studios Rare Outstanding Achievement in Soundtrack MUSIC SUPERVISOR Guitar Hero 2 Activision/Red Octane Harmonix Eric Brosius SingStar Rocks! Sony Computer Entertainment SCE London Studio Alex Hackford & Sergio Pimentel FIFA 07 Electronic Arts Electronic Arts Canada Joe Nickolls Marc Ecko's Getting Up Atari The Collective Marc Ecko, Sean "Diddy" Combs Scarface Sierra Entertainment Radical Entertainment Sound Director: Rob Bridgett Outstanding Achievement in Original Music Composition COMPOSER Call of Duty 3 Activison Treyarch Joel Goldsmith LocoRoco Sony Computer -

The History of Video Game Music from a Production Perspective

Digital Worlds: The History of Video Game Music From a Production Perspective by Griffin Tyler A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree, Bachelor in Arts Music The Colorado College April, 2021 Approved by ___________________________ Date __May 3, 2021_______ Prof. Ryan Banagale Approved by ___________________________ Date ___________________May 4, 2021 Prof. Iddo Aharony 1 Introduction In the modern era of technology and connectivity, one of the most interactive forms of personal entertainment is video games. While video games are arguably at the height of popularity amid the social restrictions of the current Covid-19 pandemic, this popularity did not pop up overnight. For the past four decades video games have been steadily rising in accessibility and usage, growing from a novelty arcade activity of the late 1970s and early 1980s to the globally shared entertainment experience of today. A remarkable study from 2014 by the Entertainment Software Association found that around 58% of Americans actively participate in some form of video game use, the average player is 30 years old and has been playing games for over 13 years. (Sweet, 2015) The reason for this popularity is no mystery, the gaming medium offers storytelling on an interactive level not possible in other forms of media, new friends to make with the addition of online social features, and new worlds to explore when one wishes to temporarily escape from the monotony of daily life. One important aspect of video game appeal and development is music. A good soundtrack can often be the difference between a successful game and one that falls into obscurity. -

Uma Perspectiva Musicológica Sobre a Formação Da Categoria Ciberpunk Na Música Para Audiovisuais – Entre 1982 E 2017

Uma perspectiva musicológica sobre a formação da categoria ciberpunk na música para audiovisuais – entre 1982 e 2017 André Filipe Cecília Malhado Dissertação de Mestrado em Ciências Musicais Área de especialização em Musicologia Histórica Setembro de 2019 I Dissertação apresentada para cumprimento dos requisitos necessários à obtenção do grau de Mestre em Ciências Musicais – Área de especialização em Musicologia Histórica, realizada sob a orientação científica da Professora Doutora Paula Gomes Ribeiro. II Às duas mulheres da minha vida que permanecem no ciberespaço do meu pensamento: Sara e Maria de Lourdes E aos dois homens da minha vida com quem conecto no meu quotidiano: Joaquim e Ricardo III Agradecimentos Mesmo tratando-se de um estudo de musicologia histórica, é preciso destacar que o meu objecto, problemática, e uma componente muito substancial do método foram direccionados para a sociologia. Por essa razão, o tema desta dissertação só foi possível porque o fenómeno social da música ciberpunk resulta do esforço colectivo dos participantes dentro da cultura, e é para eles que direciono o meu primeiro grande agradecimento. Sinto-me grato a todos os fãs do ciberpunk por manterem viva esta cultura, e por construírem à qual também pertenço, e espero, enquanto aca-fã, ter sido capaz de fazer jus à sua importância e aos discursos dos seus intervenientes. Um enorme “obrigado” à Professora Paula Gomes Ribeiro pela sua orientação, e por me ter fornecido perspectivas, ideias, conselhos, contrapontos teóricos, ajuda na resolução de contradições, e pelos seus olhos de revisora-falcão que não deixam escapar nada! Como é evidente, o seu contributo ultrapassa em muito os meandros desta investigação, pois não posso esquecer tudo aquilo que me ensinou desde o primeiro ano da Licenciatura. -

Mass Effect1+2

Mass Effect1+2 ------------------------------www.levelup.comAUTO 3-DIGIT 024 Joseph Smith PO Box 33298 465 Summer Street Boston, MA 02445 GOT A PENNY? Main Menu HIT THE ARCADE This Issues Character we go This Issues Old Versus over some of the biggest names hat’s right the Penny Arcade Expo is open for reg- New we go over the in Video game development. istration and pannel submissions. PAX is one of Mass Effect series is Tthe biggest video game expo’s in the United States it as good as we all and we are bringing it to you first. hope? The people PAX is a great way to see many of the gaming commu- nities biggest people.in the game industry. Shigeru Miya- moto has made multiple appearances. One of the biggest THE RANT: this issue Bombom attractions of PAX is seeing the presenting of new games, riffs on Dragon Age: origins talking with project directors and getting to see what’s in the works. In fact one of the important internet phenom- enons is Mounty Oum. A man who became famous from building and animating many famous video game charac- ters and creating amazing cinematic battle sequences. The Games PAX is without a doubt one of the best places to meet video game enthusiasts , and Indi Video Game Developers. That BGM has hunted down the is not to say that all PAX focuses on is video games. It also Today we go over gammer one ups to get the story and brings you into the realm of pen and paper if you allow it, girls and that dreadful maybe an extra life? that is right Table Top games. -

Ludo-Musicological Typologies: Examining New Ways of Classifying, Categorizing, and Organizing Music in Video Games: Annotated Bibliography

University of Denver Digital Commons @ DU Musicology and Ethnomusicology: Student Scholarship Musicology and Ethnomusicology 11-2020 Ludo-Musicological Typologies: Examining New Ways of Classifying, Categorizing, and Organizing Music in Video Games: Annotated Bibliography Nicholas Pierce Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.du.edu/musicology_student Part of the Musicology Commons This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License. Ludo-Musicological Typologies: Examining New Ways of Classifying, Categorizing, and Organizing Music in Video Games: Annotated Bibliography Ludo-musicological Typologies: Examining new ways of classifying, categorizing, and organizing music in video games Annotated Bibliography Over the past thirty years, music in video games has grown increasingly complex and sophisticated, with many composers specializing in this medium. Composers from other mediums like film and television (Danny Elfman, Hans Zimmer, and Michael Giachinno most notably) have also begun writing for video games, in addition to their other projects. Today, video game music incorporates elements from a wide variety of musical styles and genres, and utilizes diverse compositional techniques, some unique to the medium. However, an examination of scholarly literature on the subject (ludomusicology) reveals that this diversity and variety is not always reflected in the ways that video game music is categorized, classified, and organized. I hope to use these sources, among others, to re-organize video game music and the composers thereof, to help musicians and scholars more easily understand the rich canon of music that has been written for this medium. Collins, Karen. "Video games, Music in," Grove Music Online, ed. Deane L. Root. First published 25 May 2016, updated 25 November 2018.