A Comedy of Scientific Errors BOVINES

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Development of Preservice Biology Teachers‟ Skills in the Causal Process Concerning Photosynthesis

Journal of Education and Training Studies Vol. 7, No. 4; April 2019 ISSN 2324-805X E-ISSN 2324-8068 Published by Redfame Publishing URL: http://jets.redfame.com Development of Preservice Biology Teachers‟ Skills in the Causal Process Concerning Photosynthesis Arzu Saka Correspondence: Arzu Saka, Trabzon University, Fatih Faculty of Education, Trabzon, 61335,Turkey. Received: February 12, 2019 Accepted: March 7, 2019 Online Published: March 11, 2019 doi:10.11114/jets.v7i4.4022 URL: https://doi.org/10.11114/jets.v7i4.4022 Abstract Photosynthesis is the most effective cycle and sustainable natural process known in nature. Students who learn the subject of photosynthesis well will also make better sense of other issues such as environmental problems, the state of the atmosphere, greenhouse gases, climate changes, carbon footprints and conservation of forests. The aim of this study is to present an example of a worksheet that investigates the skill levels possessed by preservice teachers‟ in the causal process, and also to examine their ability to write a photosynthesis equation by means of a history-based approach that also includes reading skills. The study was conducted with the action research method. The study sample consisted of a total of 71 preservice biology teachers. At the first stage, before the implementation of the worksheet, 34 teacher candidates from within the sample were asked a question with a diagram summarising the photosynthesis process. At the second stage, all the prospective teachers were asked for the skill levels they possessed in the causal process to be assessed via implementation of the worksheet. The answers given by the preservice teachers in the defining variables section in particular make up the least answered section of the worksheet. -

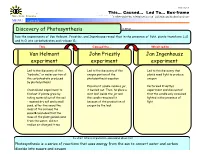

Discovery of Photosynthesis Jan Ingenhousz Experiment John

Cause / Effect TM This… Caused… Led To… Box-frame . Makes Sense Strategies © 2007 Edwin Ellis, All Rights© 2007 Reserved Edwin Published Ellis, byAll Makes Rights Sense Reserved Strategies, LLC, www.MakesSenseStrategies.com Lillian, AL www.MakesSenseStrategies.com MENU sample Name: Date: Discovery of Photosynthesis Is about … how the experiments of Van Helmont, Priestley, and Ingenhousz reveal that in the presence of light, plants transform C2O and H2O into carbohydrates and release O2. This Caused the… Which led to … Van Helmont John Priestly Jan Ingenhousz experiment experiment experiment · Led to the discovery of the · Led to the discovery of the · Led to the discovery that “hydrate,” or water portion of oxygen portion of the plants need light to produce the carbohydrate produced photosynthesis equation oxygen by photosynthesis · Placed a lit candle inside a jar, · Performed Priestly’s · Created and experiment to it burned out. Then, he place a experiment and discovered find out if plants grew by mint leaf inside the jar and that the candle only remained taking material out of the soil the candle remained lit lighted in the presence of – massed dry soil and a small because of the production of light seed, after five years the oxygen by the leaf mass of the soil was the sameèconcluded that the mass of the plant gained came from the water, did not realize air changed it too So what? What is important to understand about this? Photosynthesis is a series of reactions that uses energy from the sun to convert water and carbon dioxide into sugars and oxygen . -

Jean Senebier's Thoughts on Experimentation

| Jean Senebier’s thoughts on experimentation and their relevance for today’s researcher | 185 | Jean Senebier’s thoughts on experimentation and their relevance for today’s researcher Edward E. FARMER * Ms. received the 22nd April 2010, accepted the 10th September 2010 T Abstract How are observation and experimentation related to one another? Jean Senebier (1742-1809) tackled this question in his philosophical works on The Art of Observing. However, Senebier was not only a theoretician and, not long after his first publications on observation, his own experiments contributed to resolve a major question in biology: what do the leaves of plants feed on? By analysing Senebier’s works on science theory in parallel with those reporting his scientific discoveries, this article shows that The Art of Observing series is not restricted to observation and contains deep insights into the process of experimenting with living organisms. Keywords: Senebier, plant physiology, photosynthesis, science didactics, epistemology T Résumé Les considérations de Jean Senebier sur l’expérimentation et leur intérêt pour les chercheurs d’aujourd’hui. – Quel est le lien entre l’observation et l’expérimentation? Jean Senebier (1742-1809) a abordé cette question dans sa série d’ouvrages sur l’Art d’observer. Cependant, Senebier n’était pas seulement un théoricien et, peu après ses premières publi - cations sur l’observation, il a commencé à travailler sur l’une des grandes questions de la biologie: « de quoi se nourrissent les feuilles des plantes? » S’appuyant sur ce qu’il avait appris en tant qu’expérimentaliste, Senebier a par la suite été en mesure d’approfondir ses brillantes analyses présentées dans ses deux premières publications sur l’Art d’observer. -

Photosynthesis Photosynthesis

Unit 5 Photosynthesis UNIT 5 PHOTOSYNTHESIS Structure 5.1 Introduction 5.4 Role of Sunlight Objectives Electromagnetic Spectrum 5.2 Basic Concepts – Historical Absorption and Action Background Spectrum Earlier Investigations Absorption of Photons – Energy States of Chlorophyll Development of Concept – Formulation of Equation of 5.5 Summary Photosynthesis 5.6 Terminal Questions 5.3 Photosynthetic Pigments 5.7 Answers Essential Pigments : Chlorophylls Accessory Pigments Non-Photosynthetic Pigments and Photoreceptors 5.1 INTRODUCTION In this Unit you will be studying the plant pigments including non- photosynthetic pigments and sunlight, which are required for photosynthesis— a process by which green plants and certain other organisms transform light energy into chemical energy in the form of sugars. This sugar can then be converted to other carbohydrates or other food materials like fats and proteins. The general importance of the process was recognized as long ago as 2000 years. The biblical saint, Isaiah, who lived between 700-600 B.C. said “All flesh is grass” recognizing that all food chains are finally traced to plants. Plants are also responsible for the fossil fuels such as petroleum, oil, and coal, which represent products of photosynthesis carried out millions of years ago in the carboniferous era. It is through this process that plants continuously purify air during daytime and thus allow animals to breathe. The overall importance of this process is best expressed in the words of Eugene Rabinowitch, one of the great authors and -

The 100 Most Influential Scientists of All Time / Edited by Kara Rogers.—1St Ed

Published in 2010 by Britannica Educational Publishing (a trademark of Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc.) in association with Rosen Educational Services, LLC 29 East 21st Street, New York, NY 10010. Copyright © 2010 Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, and the Thistle logo are registered trademarks of Encyclopædia Britannica, Inc. All rights reserved. Rosen Educational Services materials copyright © 2010 Rosen Educational Services, LLC. All rights reserved. Distributed exclusively by Rosen Educational Services. For a listing of additional Britannica Educational Publishing titles, call toll free (800) 237-9932. First Edition Britannica Educational Publishing Michael I. Levy: Executive Editor Marilyn L. Barton: Senior Coordinator, Production Control Steven Bosco: Director, Editorial Technologies Lisa S. Braucher: Senior Producer and Data Editor Yvette Charboneau: Senior Copy Editor Kathy Nakamura: Manager, Media Acquisition Kara Rogers: Senior Editor, Biomedical Sciences Rosen Educational Services Jeanne Nagle: Senior Editor Nelson Sá: Art Director Introduction by Kristi Lew Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data The 100 most influential scientists of all time / edited by Kara Rogers.—1st ed. p. cm.—(The Britannica guide to the world’s most influential people) “In association with Britannica Educational Publishing, Rosen Educational Services.” Includes index. ISBN 978-1-61530-040-2 (eBook) 1. Science—Popular works. 2. Science—History—Popular works. 3. Scientists— Biography—Popular works. I. Rogers, Kara. -

Evolution of Photosynthesis

Evolution of photosynthesis The evolution of photosynthesis refers to the origin and subsequent evolution of photosynthesis, the process by which light energy synthesizes sugars from carbon dioxide and water, releasing oxygen as a waste product. The process of photosynthesis was discovered by Jan Ingenhousz, a Dutch-born British physician and scientist, first publishing about it in 1779.[1] The first photosynthetic organisms probably evolved early in the evolutionary history of life and most likely used reducing agents such as hydrogen or electrons, rather than water.[2] There are three major metabolic pathways by which photosynthesis is carried out: C3 photosynthesis, C4 photosynthesis, and CAM photosynthesis. C3 photosynthesis is the oldest and most common form. C3 is a plant that uses the calvin cycle for the initial steps that incorporate CO2 into organic material. C4 is a plant that prefaces the calvin cycle with reactions that incorporate CO2 into four-carbon compounds. CAM is a plant that uses crassulacean acid metabolism, an adaptation for photosynthesis in arid conditions. C4 and CAM Plants have special adaptations that save water.[3] Contents Origin Symbiosis and the origin of chloroplasts Evolution of photosynthetic pathways Concentrating carbon Evolutionary record When is C4 an advantage? See also References Origin The biochemical capacity to use water as the source for electrons in photosynthesis Life timeline evolved in a common ancestor of extant Ice Ages Quater n0ar y— Primates ← [4] Flowers Earliest apes cyanobacteria. The geological record P Birds h Mammals – Plants Dinosaurs indicates that this transforming event took Karo o a n ← Andean Tetrapoda place early in Earth's history, at least 2450– -50 0 — e Arthropods Molluscs r ←Cambrian explosion 2320 million years ago (Ma), and, it is o ← Cryoge nian Ediacara biota [5][6] – z ← speculated, much earlier. -

An Unfolding Discovery

Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA Vol. 68, No. 11, pp. 2875, November 1971 Photosynthesis Bicentennial Symposium: Introduction by the Chairman KENNETH V. THIMANN Crown College, University of California, Santa CruG, Calif. 95060 In early August 1771 Joseph Priestley, chemist of Birmingham, mainly from the underside of the leaves. But the biological England, and codiscoverer of oxygen, performed his famous "climate" was not ready for the correct interpretation of the experiment with the mouse and the mint plant. This experi- bubbles and Bonnet's discussion was wholly in terms of heat- ment provided the beginnings of our understanding of that ing and the consequent expansion of gases at the leaf surface. remarkable process whereby the organic matter of our bio- In the following symposium Eugene Rabinowitch presents sphere is produced and our atmosphere continuously purified. It is perhaps not widely known that the discovery was al- the sequential development of the leading ideas in the action most made some 20 years earlier by Joseph Bonnet, another of light on leaves, and then the current developments in the very active researcher of the time. For Bonnet observed that physiological, biochemical and photochemical aspects of the when leaves were immersed in water and exposed to sunlight, field at the present day are summarized by some of the leaders bubbles of gas were produced. He even noted that they came in the study of these aspects of photosynthesis in this country. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA Vol. 68, No. 11, pp. 2875-2876, November 1971 An Unfolding Discovery EUGENE RABINOWITCH State University of New York, Albany, New York, 12203 About 1648, a Dutch alchemist, van Helmont, grew a willow "Experiments and Observations on Different Kinds of Air". -

Botany Coursebook

The Global STEM School Botany Coursebook Student Edition Acta Non Verba www.dexterschool.org The Plant World What is Botany? Botany is the scientific study of plants! Why does Botany matter? Look outside, what do you see? Plants! We live in a plant world called Earth. From the air you breathe to the food you eat - plants make your life possible! By better understanding how plants work we can improve our lives. Imagine... Look outside and imagine all of the plants suddenly disappeared. Write a few sentences or draw a picture below about why this would be a bad thing. Botany The Plant World What is a plant? A plant is a living organism that grows in the ground, usually has leaves or flowers, and needs sun and water to survive. They come in all shapes and sizes, but most plants contain a green pigment called chlorophyll. Circle the ones you think are plants: Botany The Plant World Not a Plant Plants usually have flowers or leaves, need sun and water to survive, and most have chlorophyll. There are a several organisms you might think are plants, but aren’t! Corals Colorals are underwater animals with a hard exterior skeletal structure. They do not make their own food - instead they capture food and eat it through tiny mouths! Algae Although green, algae do not have roots, stems, and leaves. They’re considered bacteria, not plants and can only live in water. Fungi Fungi (mushrooms) have a way of getting food that’s completely different than plants. In fact, they’re more closely related to animals than to plants! Botany The Plant World Plant vs Not a Plant Activity Go outside or look through the window and draw three examples of plants vs non-plants. -

Dr Jan Ingenhousz, Or Why Don't We Know Who Discovered Photosynthesis?

paper 1st Conference of the European Philosophy of Science Association Madrid, 15-17 November 2007 Dr Jan IngenHousz, or why don't we know who discovered photosynthesis? Geerdt Magiels1 Abstract Who discovered photosynthesis? Not many people know. Jan IngenHousz' name has been forgotten, his life and works have disappeared in the mists of time. Still, the tale of his scientific endeavour shows science in action. Not only does it open up an undisclosed chapter of the history of science, it is an ideal (as under researched) episode in the history of science that can help to shine some light on the ingredients and processes that shape the development of science. This paves the way for a fresh multidimensional approach in the philosophy of science: towards an "ecology of science". Introduction Unravelling the story of Jan IngenHousz will twine strands of history of science and of philosophy of science together in equal measures. Imre Lakatos' dictum will be expanded fully in this particular examination of a very specific episode in the development of scientific knowledge: "Philosophy of science without history is empty; history of science without philosophy of science is blind."1 The materials on which this study is based are as diverse as coherent. The officially published books ands articles by IngenHousz form the obvious core of this study, but equally important are the letters, travel notes and diaries of IngenHousz that have been until now not properly researched. A third important element in this approach will be the reconstruction of the scientific experiments IngenHousz conducted, with the help of the detailed instructions he himself wrote for the proper design and use of the so-called eudiometer. -

A 'Misplaced Chapter' in the History Of

Photosynthesis Research 53: 65±72, 1997. 65 c 1997 Kluwer Academic Publishers. Printed in the Netherlands. Historical corner A `misplaced chapter' in the history of photosynthesis research; the second publication (1796) on plant processes by Dr Jan Ingen-Housz, MD, discoverer of photosynthesis A bicentenniel `resurrection' Howard Gest Photosynthetic Bacteria Group, Biology Department and Department of History and Philosophy of Science, Indiana University, Bloomington, IN 47405, USA Received 10 October 1996; accepted in revised form 5 December 1996 Key words: discovery of photosynthesis, Ingen-Housz, Lavoisier Abstract In 1779, the Dutch physician Jan Ingen-Housz (1730±1799) obtained a leave-of-absence from his post as Court Physician to Empress Maria Theresa of Austria in order to do research (in England) on plants during the summer months. He performed more than 500 experiments, and described the results in his exceptional book Experiments Upon Vegetables (1779). In addition to proving the requirement for light in photosynthesis, Ingen-Housz established that leaves were the primary sites of the photosynthetic process. Later, Ingen- Housz published research papers on various subjects but aside from his 1779 book, he published only one more communication on photosynthesis and plant physiology. This was entitled `An Essay on the Food of Plants and the Renovation of Soils'. The essay was published in 1796 as an appendix to an obscure British government report, which is rare and virtually unknown. The present paper describes the 1796 essay, which is particularly interesting in that it shows how Ingen-Housz's concepts were modi®ed by new interpretations of chemical phenomena described in Lavoisier's great and revolutionary book Traite El ementaire de Chimie (1789). -

Introduction to Botany. Lecture 19

Questions and answers Leaves Photosynthesis Introduction to Botany. Lecture 19 Alexey Shipunov Minot State University October 12, 2012 Shipunov Introduction to Botany. Lecture 19 Questions and answers Leaves Photosynthesis Outline 1 Questions and answers 2 Leaves Ecological adaptations of leaves 3 Photosynthesis Animals can do that, too History Shipunov Introduction to Botany. Lecture 19 Questions and answers Leaves Photosynthesis Outline 1 Questions and answers 2 Leaves Ecological adaptations of leaves 3 Photosynthesis Animals can do that, too History Shipunov Introduction to Botany. Lecture 19 Questions and answers Leaves Photosynthesis Outline 1 Questions and answers 2 Leaves Ecological adaptations of leaves 3 Photosynthesis Animals can do that, too History Shipunov Introduction to Botany. Lecture 19 Deficit of oxygen and carbon dioxide Fungi and bacteria Soil removal Questions and answers Leaves Photosynthesis Previous final question: the answer Why plants are dying in the flood? Shipunov Introduction to Botany. Lecture 19 Questions and answers Leaves Photosynthesis Previous final question: the answer Why plants are dying in the flood? Deficit of oxygen and carbon dioxide Fungi and bacteria Soil removal Shipunov Introduction to Botany. Lecture 19 Questions and answers Leaves Ecological adaptations of leaves Photosynthesis Leaves Ecological adaptations of leaves Shipunov Introduction to Botany. Lecture 19 Questions and answers Leaves Ecological adaptations of leaves Photosynthesis Plants and light Sciophytes Heliophytes Shipunov Introduction to Botany. Lecture 19 Questions and answers Leaves Ecological adaptations of leaves Photosynthesis Sciophyte and heliophyte Oxalis acetosella and Sylphium laciniatum Shipunov Introduction to Botany. Lecture 19 Questions and answers Leaves Ecological adaptations of leaves Photosynthesis Plants and soil Halophytes (accumulate, excrete or avoid NaCl) Nitrate halophytes (grow on soils rich of NaNO3) Oxylophytes (grow on acidic soils) Calciphytes (grow on chalk soils rich of CaCO3) Shipunov Introduction to Botany. -

Spectrum of Light As a Determinant of Plant Functioning: a Historical Perspective

life Review Spectrum of Light as a Determinant of Plant Functioning: A Historical Perspective Oxana S. Ptushenko 1, Vasily V. Ptushenko 2,3,4,* and Alexei E. Solovchenko 5,6 1 Faculty of Bioengineering and Bioinformatics, Lomonosov Moscow State University, 119234 Moscow, Russia; [email protected] 2 A.N. Belozersky Institute of Physico-Chemical Biology, Lomonosov Moscow State University, 119992 Moscow, Russia 3 N.M. Emanuel Institute of Biochemical Physics of Russian Academy of Sciences, 119334 Moscow, Russia 4 N.N. Semenov Federal Research Center for Chemical Physics, 119991 Moscow, Russia 5 Faculty of Biology, M.V. Lomonosov Moscow State University, 119234 Moscow, Russia; [email protected] 6 Institute of Medicine and Experimental Biology, Pskov State University, 180000 Pskov, Russia * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 20 January 2020; Accepted: 12 March 2020; Published: 17 March 2020 Abstract: The significance of the spectral composition of light for growth and other physiological functions of plants moved to the focus of “plant science” soon after the discovery of photosynthesis, if not earlier. The research in this field recently intensified due to the explosive development of computer-controlled systems for artificial illumination and documenting photosynthetic activity. The progress is also substantiated by recent insights into the molecular mechanisms of photo-regulation of assorted physiological functions in plants mediated by photoreceptors and other pigment systems. The spectral balance of solar radiation can vary significantly, affecting the functioning and development of plants. Its effects are evident on the macroscale (e.g., in individual plants growing under the forest canopy) as well as on the meso- or microscale (e.g., mutual shading of leaf cell layers and chloroplasts).