Texts and Documents

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Evolution of Bowood House and Estate Since 1945

The Evolution of Bowood House and Estate Since 1945 Illustrated talk by the Most Hon. the Marquess of Lansdowne By Dr Robert Blackburn The 14th Joint Annual Civic Society lecture (in conjunction with the Friends of St Andrew’s) was held in St Andrew’s Church, Chippenham, 21 June 2016 by kind permission of the Vicar, the Rev. Rod Key, and in the presence of the Mayor of Chippenham , Cllr Terry Gibson , and Mrs Gibson. Lord Lansdowne was introduced by Mike Stone, Chair of the Civic Society. Bowood Park was once part of the Royal Forest of Chippenham. Today, it is part of the Historic Houses Association (the HHA), which markets itself separately, outside the National Trust and English Heritage. Lord Lansdowne said that he regarded himself as the custodian of Bowood, not just the owner. He had been in this role since 1972, when his father, the 8th Marquess, born in 1912, retired to Perthshire when he turned 60. During the 44 years since, there have been many challenges and anxieties, as well as pleasures, and the purpose of this talk was to outline some of these, offering a picture of the development of the Lord Lansdowne giving his talk at the Joint Annual Civic Bowood Estate over the decades Society Lecture. since the Second World War. Lord Lansdowne showed a map of the Bowood Estate as it was in 1900. At that time, it consisted of 12,000 acres, including most of the town of Calne. Today, in 2016, the estate’s acreage has fallen to 4,000, mostly agriculture, let for farming. -

2019 Group Visits 30Th March - 3Rd November 2019 Welcome to Bowood House & Gardens

2019 Group Visits 30th March - 3rd November 2019 Welcome to Bowood House & Gardens Welcome to Bowood House & Gardens; home to the Marquis and Marchioness of Lansdowne. Bowood House sits in 2000 acres of Grade 1 listed ‘Capability’ Brown parkland and offers exclusive tours around the award winning Private Walled Garden and the opportunity to discover the rich history of the House. Visit the Woodland Gardens in spring and take in the vibrant colours from over 30 acres of bluebells, azaleas and rhododendrons. Bowood is perfectly primed to welcome groups of 15 or more to suit varying interests for a truly memorable visit. “Our philosophy has been to try and provide something for all ages. We have developed the House & Gardens to preserve its history, but at the same time make it fun, exciting and interesting to visit. We extend a warm welcome to all our visitors” The Marquis of Lansdowne House & Gardens Admissions Enjoy a beautiful day visiting Bowood House & Gardens, home to the Lansdowne family since 1754. Bowood House is steeped in history and has seen vast changes, from the 2nd Earl beginning major improvements to the interiors, using renowned architect Robert Adam, to the ‘Large House’ being demolished after the Second World War when it fell into disrepair. Napoleon’s death mask, Queen Victoria’s wedding chair and the laboratory in which Dr. Joseph Priestley identified Oxygen gas are among the collection of art and historical treasures which provide interest for all ages. A visit to the House & Gardens can be tailored to suit both those wishing to spend a full day out or have an enjoyable short visit between other attractions. -

Feb-2018-Final-No-Legacy-2.Pdf

VISIT TO TREDEGAR HOUSE, NEWPORT Tuesday 20 March 2018 Depart: Jacob’s Wells Road 9.45am Christchurch 10.00am Clifton Cathedral 10.05am. Tredegar House is one of the architectural wonders of Wales. For over 500 years it was the home of one of the greatest Welsh families – the Morgans – and later Lord Tredegar. One can visit the magnificent state rooms, the elegant family apartments and a warren of rooms below stairs. The house is set in 90 acres of parkland with lakeside walks and formal gardens to explore. The impressive Grade 1 listed stables are worth a visit. Cost £19 for NT members. This includes coach fare, coffee/tea on arrival and the driver’s gratuity. (NB non-NT members will be responsible for paying their own entrance) Please complete the enclosed booking form and send it with a cheque payable to Clifton Garden Society by Tuesday 6 March to Gillian Joseph, 46 Princess Victoria Street, Clifton, Bristol BS8 4BZ. Tel: 0117 973 7296 ************************************************************************************************ VISIT TO HANBURY HALL, WORCESTERSHIRE Wednesday 25 April 2018 Depart: Jacob`s Wells Road at 9.00am Christchurch 9.15am Clifton Cathedral 9.20am The house and gardens were originally a stage set for summer parties and offer a glimpse into life at the turn of the 18th century. The original formal gardens designed by George London have been faithfully re-created with an orangery, orchards and walled garden. In the Parkland is George London`s visionary Semicircle which sounds worth a visit. Tours of the house are included. Light refreshments are served in the walled garden or in Elsie`s tearoom in the house in colder weather. -

Saltram House: the Evolution of an Eighteenth-Century Country Estate

University of Plymouth PEARL https://pearl.plymouth.ac.uk 04 University of Plymouth Research Theses 01 Research Theses Main Collection 2020 Saltram House: The Evolution of an Eighteenth-Century Country Estate Norley, Katherine R http://hdl.handle.net/10026.1/16730 University of Plymouth All content in PEARL is protected by copyright law. Author manuscripts are made available in accordance with publisher policies. Please cite only the published version using the details provided on the item record or document. In the absence of an open licence (e.g. Creative Commons), permissions for further reuse of content should be sought from the publisher or author. Saltram House: The Evolution of an Eighteenth-Century Country Estate By Katherine R Norley A thesis submitted to the University of Plymouth in partial fulfilment for the degree of RESEARCH MASTERS School of Humanities and Performing Arts December 2020 1 This copy of the thesis has been supplied on condition that anyone who consults it is understood to recognise that its copyright rests with its author and that no quotation from the thesis and no information derived from it may be published without the author’s prior consent. 2 Author’s Declaration At no time during the registration for the degree of Research Masters has the author been registered for any other University award without prior agreement of the Doctoral College Quality Sub-Committee. Work Submitted for this research degree at the University of Plymouth has not formed part of any other degree either at the University of Plymouth or at another establishment. This study was financed with the aid of government funding. -

A Comedy of Scientific Errors BOVINES

SACRED A COMEDY OF SCIENTIFIC ERRORS BOVINES DOUGLAS ALLCHIN, DEPARTMENT EDITOR William Shakespeare may well have foreshadowed the modern television experiment with balm, groundsel, and spinach. All modified the air to sitcom. His comic misadventures were expertly crafted. In A Comedy of support sustained burning. Animals, too, could breathe longer in the Errors, for example, twins (with twin servants), each separated at birth, treated air. Plants, Priestley had found, could restore the “goodness” of converge unbeknownst to each other in the same town. Mistaken iden- the air depleted by respiration or combustion. American correspondent tity leads to miscommunication. More mistaken identity follows, with Benjamin Franklin immediately perceived the global implications: plants more misdelivered messages and yet more misinterpretations. Hilarious help restore the atmosphere that humans and other animals foul. The consequences ensue. It is a stock comedic formula in modern entertain- system ensures our survival. That view fit neatly with Priestley’s religious ment. A character first makes an unintentional error. Then ironically, in belief in an intentionally designed (and rational) natural world. It was a trying to correct it, things only get laughably worse. remarkable discovery. For this and other work on airs, the Royal Society Science, we imagine, is safeguarded against such embarrassing in 1772 awarded Priestley the Copley Medal, then the most prestigious episodes. In the lore of scientists, echoed among teachers, science is honor in science. “self-correcting.” Replication, in particular, ensures that errors are Others were eager to build on Priestley’s discovery about plants and exposed for what they are. Research promptly returns to its fruitful tra- the restoration of air. -

Development of Preservice Biology Teachers‟ Skills in the Causal Process Concerning Photosynthesis

Journal of Education and Training Studies Vol. 7, No. 4; April 2019 ISSN 2324-805X E-ISSN 2324-8068 Published by Redfame Publishing URL: http://jets.redfame.com Development of Preservice Biology Teachers‟ Skills in the Causal Process Concerning Photosynthesis Arzu Saka Correspondence: Arzu Saka, Trabzon University, Fatih Faculty of Education, Trabzon, 61335,Turkey. Received: February 12, 2019 Accepted: March 7, 2019 Online Published: March 11, 2019 doi:10.11114/jets.v7i4.4022 URL: https://doi.org/10.11114/jets.v7i4.4022 Abstract Photosynthesis is the most effective cycle and sustainable natural process known in nature. Students who learn the subject of photosynthesis well will also make better sense of other issues such as environmental problems, the state of the atmosphere, greenhouse gases, climate changes, carbon footprints and conservation of forests. The aim of this study is to present an example of a worksheet that investigates the skill levels possessed by preservice teachers‟ in the causal process, and also to examine their ability to write a photosynthesis equation by means of a history-based approach that also includes reading skills. The study was conducted with the action research method. The study sample consisted of a total of 71 preservice biology teachers. At the first stage, before the implementation of the worksheet, 34 teacher candidates from within the sample were asked a question with a diagram summarising the photosynthesis process. At the second stage, all the prospective teachers were asked for the skill levels they possessed in the causal process to be assessed via implementation of the worksheet. The answers given by the preservice teachers in the defining variables section in particular make up the least answered section of the worksheet. -

University Microfilms 300 North Zaeb Road Ann Arbor

INFORMATION TO USERS This dissertation was produced from a microfilm copy of the original document. While the most advanced technological means to photograph and reproduce this document have been used, the quality is heavily dependent upon the quality of the original submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help you understand markings or patterns which may appear on this reproduction. 1. The sign or "target" for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is "Missing Page(s)". If it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting thru an image and duplicating adjacent pages to insure you complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a large round black mark, it is an indication that the photographer suspected that the copy may have moved during exposure and thus cause a blurred image. You will find a good image of the page in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., was part of the material being photographed the photographer followed a definite method in "sectioning" the material. It is customary to begin photoing at the upper left hand corner of a large sheet and to continue photoing from left to right in equal sections with a small overlap. If necessary, sectioning is continued again — beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete. 4. The majority of users indicate that the textual content is of greatest value, however, a somewhat higher quality reproduction could be made from "photographs" if essential to the understanding of the dissertation. -

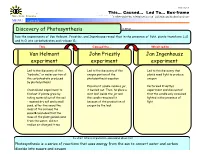

Discovery of Photosynthesis Jan Ingenhousz Experiment John

Cause / Effect TM This… Caused… Led To… Box-frame . Makes Sense Strategies © 2007 Edwin Ellis, All Rights© 2007 Reserved Edwin Published Ellis, byAll Makes Rights Sense Reserved Strategies, LLC, www.MakesSenseStrategies.com Lillian, AL www.MakesSenseStrategies.com MENU sample Name: Date: Discovery of Photosynthesis Is about … how the experiments of Van Helmont, Priestley, and Ingenhousz reveal that in the presence of light, plants transform C2O and H2O into carbohydrates and release O2. This Caused the… Which led to … Van Helmont John Priestly Jan Ingenhousz experiment experiment experiment · Led to the discovery of the · Led to the discovery of the · Led to the discovery that “hydrate,” or water portion of oxygen portion of the plants need light to produce the carbohydrate produced photosynthesis equation oxygen by photosynthesis · Placed a lit candle inside a jar, · Performed Priestly’s · Created and experiment to it burned out. Then, he place a experiment and discovered find out if plants grew by mint leaf inside the jar and that the candle only remained taking material out of the soil the candle remained lit lighted in the presence of – massed dry soil and a small because of the production of light seed, after five years the oxygen by the leaf mass of the soil was the sameèconcluded that the mass of the plant gained came from the water, did not realize air changed it too So what? What is important to understand about this? Photosynthesis is a series of reactions that uses energy from the sun to convert water and carbon dioxide into sugars and oxygen . -

Jean Senebier's Thoughts on Experimentation

| Jean Senebier’s thoughts on experimentation and their relevance for today’s researcher | 185 | Jean Senebier’s thoughts on experimentation and their relevance for today’s researcher Edward E. FARMER * Ms. received the 22nd April 2010, accepted the 10th September 2010 T Abstract How are observation and experimentation related to one another? Jean Senebier (1742-1809) tackled this question in his philosophical works on The Art of Observing. However, Senebier was not only a theoretician and, not long after his first publications on observation, his own experiments contributed to resolve a major question in biology: what do the leaves of plants feed on? By analysing Senebier’s works on science theory in parallel with those reporting his scientific discoveries, this article shows that The Art of Observing series is not restricted to observation and contains deep insights into the process of experimenting with living organisms. Keywords: Senebier, plant physiology, photosynthesis, science didactics, epistemology T Résumé Les considérations de Jean Senebier sur l’expérimentation et leur intérêt pour les chercheurs d’aujourd’hui. – Quel est le lien entre l’observation et l’expérimentation? Jean Senebier (1742-1809) a abordé cette question dans sa série d’ouvrages sur l’Art d’observer. Cependant, Senebier n’était pas seulement un théoricien et, peu après ses premières publi - cations sur l’observation, il a commencé à travailler sur l’une des grandes questions de la biologie: « de quoi se nourrissent les feuilles des plantes? » S’appuyant sur ce qu’il avait appris en tant qu’expérimentaliste, Senebier a par la suite été en mesure d’approfondir ses brillantes analyses présentées dans ses deux premières publications sur l’Art d’observer. -

What's New in Gardens 2016

WHAT’S NEW IN GARDENS 2016 2016 marks the 300th anniversary of the birth of England's greatest gardener, Lancelot ‘Capability’ Brown, best- known for designing gardens at some of the country's greatest stately homes including Blenheim Palace, Chatsworth, Highclere Castle, Burghley and Compton Verney. Capability Brown's landscape gardens are synonymous with England's green and pleasant land, with their seemingly natural rolling hills, curving lakes, flowing rivers and majestic trees. The Capability Brown Festival, a nationwide festival and programme of events, will take place throughout 2016, with the opportunity to visit over 150 Brown gardens and sites, including some not usually open to visitors. This celebration of the iconic and celebrated English landscaper is set to put a spotlight on and showcase the fabulous gardens and estates right across the country, from the grand Brown-designed estates to private urban gardens not usually open to the public (and everything in between). Here, VisitEngland rounds up some of the biggest news, openings and developments in English gardens in 2016… JANUARY Painting the Modern Garden: Monet to Matisse, Royal Academy of Arts, London 30 January – 20 April 2016 This major exhibition will examine the role of gardens in the paintings of Claude Monet and his contemporaries. With Money as the starting point, the exhibition will span the early 1860s to the 1920s and will include Impressionist, Post-Impressionist and Avant-Garde artists of the early 20th century. It will bring together more than 120 works from public institutions and private collections, including 35 paintings by Monet alongside rarely- seen masterpieces by Paul Klee, Emil Nolde, Gustav Klimt and Wassily Kandinsky. -

Photosynthesis Photosynthesis

Unit 5 Photosynthesis UNIT 5 PHOTOSYNTHESIS Structure 5.1 Introduction 5.4 Role of Sunlight Objectives Electromagnetic Spectrum 5.2 Basic Concepts – Historical Absorption and Action Background Spectrum Earlier Investigations Absorption of Photons – Energy States of Chlorophyll Development of Concept – Formulation of Equation of 5.5 Summary Photosynthesis 5.6 Terminal Questions 5.3 Photosynthetic Pigments 5.7 Answers Essential Pigments : Chlorophylls Accessory Pigments Non-Photosynthetic Pigments and Photoreceptors 5.1 INTRODUCTION In this Unit you will be studying the plant pigments including non- photosynthetic pigments and sunlight, which are required for photosynthesis— a process by which green plants and certain other organisms transform light energy into chemical energy in the form of sugars. This sugar can then be converted to other carbohydrates or other food materials like fats and proteins. The general importance of the process was recognized as long ago as 2000 years. The biblical saint, Isaiah, who lived between 700-600 B.C. said “All flesh is grass” recognizing that all food chains are finally traced to plants. Plants are also responsible for the fossil fuels such as petroleum, oil, and coal, which represent products of photosynthesis carried out millions of years ago in the carboniferous era. It is through this process that plants continuously purify air during daytime and thus allow animals to breathe. The overall importance of this process is best expressed in the words of Eugene Rabinowitch, one of the great authors and -

Landscape & Gardens

CATALOGUE #21 LANDSCAPE & GARDENS WITH A SECTION ON ROCK GARDENS WOODBURN BOOKS, ABAA, ILAB P.O. BOX 398 HOPEWELL, NEW JERSEY USA 08525 (609) 466-0522 [email protected] woodburnbooks.com ABBREVIATIONS: bds. - boards (i.e., the hard material of which book covers are made) bkpl. - bookplate L. - London ca. - circa libr. - library DJ - dust jacket ltd. - limited ed. - editor, edition p., pp. - page (s) endpp. - endpapers pl., pls. - plate (s) engr (s). - engraving (s) ptg. - printing enlg. - enlarged rev. - revised fly - the first free blank page rubbed - binding worn in spots foxing - brown spots on pages shaken - binding somewhat loose caused by paper impurities sq. - square frontis. - frontispiece VG - very good condition G - good condition wraps - paper covers illus. - illustrated, illustrations “+” or “ - ” indicates plus (better) or minus (worse) condition ( ) indicates that the information within parentheses is found in the book, but is not on the title page [ ] indicates that the information within brackets is derived from a source external to the book BOOK CONDITION AND SIZES: All books are bound in cloth unless noted. Condition grades include: Fine - no defects. Very good (VG) - some minor signs of wear. Good (G) - the average used and worn book with defects described. 8vo. (octavo) - 9” tall (the size of all books unless otherwise noted) Folio - 15” tall 16mo. (sixteenmo) - 5.5” tall 4to. (quarto) - 12” tall 24mo. (twentyfourmo) - 4” tall 12mo. (twelvemo) - 7” tall 32mo. (thirtytwomo) - 3” tall Copyright June 2015, Woodburn Books WOODBURN BOOKS, ABAA, ILAB P.O. BOX 398 HOPEWELL, NEW JERSEY USA 08525 (609) 466-0522 [email protected] woodburnbooks.com Catalogue #21 LANDSCAPE AND GARDENS WITH A SECTION ON ROCK GARDENS June 2015 Dear Customers and Friends, Change, change, change.