Dr Jan Ingenhousz, Or Why Don't We Know Who Discovered Photosynthesis?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Notes to the Note on the Text and Introduction

Notes Notes to the Note on the Text and Introduction i. Mandeville’s address is repeated at the end of the Preface: “From my House in Manchester-Court, Channel-Row, Westminster.” ii. A Treatise of the Hypochondriack and Hysterick Passions, vulgarly call’d the hypo in men and vapours in women; In which the Symptoms, Causes, and Cure of those Diseases are set forth after a Method intirely new. The whole interspers’d, with Instructive Discourses on the Real art of Physick it self; And Entertaining Remarks on the Modern Practice of Physicians and Apothecaries; Very useful to all, that have the Misfortune to stand in need of either. In three dialogues. By B. de Mandeville, M.D. (London, printed for and to be had of the author, at his house in Manchester-Court, in Channel- Row, Westminster; and D. Leach, in the Little-Old-Baily, and W. Taylor, at the Ship in Pater-Noster-Row, and J. Woodward in Scalding-Alley, near Stocks-Market, 1711). The second 1711 issue bears the following publica- tion details: “London, printed and sold by Dryden Leach, in Elliot’s Court, in the Little-Old-Baily, and W. Taylor, at the Ship in Pater-Noster-Row, 1711”. The 1715 reprint bears the same title with different publication details (London, printed by Dryden Leach, in Elliot’s Court, in the Little Old-Baily, and sold by Charles Rivington, at the Bible and Crown, near the Chapter-House in St. Paul’s Church Yard, 1715). A Treatise of the Hypochondriack and Hysterick Diseases. In three dialogues. -

Spontaneous Generation & Origin of Life Concepts from Antiquity to The

SIMB News News magazine of the Society for Industrial Microbiology and Biotechnology April/May/June 2019 V.69 N.2 • www.simbhq.org Spontaneous Generation & Origin of Life Concepts from Antiquity to the Present :ŽƵƌŶĂůŽĨ/ŶĚƵƐƚƌŝĂůDŝĐƌŽďŝŽůŽŐLJΘŝŽƚĞĐŚŶŽůŽŐLJ Impact Factor 3.103 The Journal of Industrial Microbiology and Biotechnology is an international journal which publishes papers in metabolic engineering & synthetic biology; biocatalysis; fermentation & cell culture; natural products discovery & biosynthesis; bioenergy/biofuels/biochemicals; environmental microbiology; biotechnology methods; applied genomics & systems biotechnology; and food biotechnology & probiotics Editor-in-Chief Ramon Gonzalez, University of South Florida, Tampa FL, USA Editors Special Issue ^LJŶƚŚĞƚŝĐŝŽůŽŐLJ; July 2018 S. Bagley, Michigan Tech, Houghton, MI, USA R. H. Baltz, CognoGen Biotech. Consult., Sarasota, FL, USA Impact Factor 3.500 T. W. Jeffries, University of Wisconsin, Madison, WI, USA 3.000 T. D. Leathers, USDA ARS, Peoria, IL, USA 2.500 M. J. López López, University of Almeria, Almeria, Spain C. D. Maranas, Pennsylvania State Univ., Univ. Park, PA, USA 2.000 2.505 2.439 2.745 2.810 3.103 S. Park, UNIST, Ulsan, Korea 1.500 J. L. Revuelta, University of Salamanca, Salamanca, Spain 1.000 B. Shen, Scripps Research Institute, Jupiter, FL, USA 500 D. K. Solaiman, USDA ARS, Wyndmoor, PA, USA Y. Tang, University of California, Los Angeles, CA, USA E. J. Vandamme, Ghent University, Ghent, Belgium H. Zhao, University of Illinois, Urbana, IL, USA 10 Most Cited Articles Published in 2016 (Data from Web of Science: October 15, 2018) Senior Author(s) Title Citations L. Katz, R. Baltz Natural product discovery: past, present, and future 103 Genetic manipulation of secondary metabolite biosynthesis for improved production in Streptomyces and R. -

A Comedy of Scientific Errors BOVINES

SACRED A COMEDY OF SCIENTIFIC ERRORS BOVINES DOUGLAS ALLCHIN, DEPARTMENT EDITOR William Shakespeare may well have foreshadowed the modern television experiment with balm, groundsel, and spinach. All modified the air to sitcom. His comic misadventures were expertly crafted. In A Comedy of support sustained burning. Animals, too, could breathe longer in the Errors, for example, twins (with twin servants), each separated at birth, treated air. Plants, Priestley had found, could restore the “goodness” of converge unbeknownst to each other in the same town. Mistaken iden- the air depleted by respiration or combustion. American correspondent tity leads to miscommunication. More mistaken identity follows, with Benjamin Franklin immediately perceived the global implications: plants more misdelivered messages and yet more misinterpretations. Hilarious help restore the atmosphere that humans and other animals foul. The consequences ensue. It is a stock comedic formula in modern entertain- system ensures our survival. That view fit neatly with Priestley’s religious ment. A character first makes an unintentional error. Then ironically, in belief in an intentionally designed (and rational) natural world. It was a trying to correct it, things only get laughably worse. remarkable discovery. For this and other work on airs, the Royal Society Science, we imagine, is safeguarded against such embarrassing in 1772 awarded Priestley the Copley Medal, then the most prestigious episodes. In the lore of scientists, echoed among teachers, science is honor in science. “self-correcting.” Replication, in particular, ensures that errors are Others were eager to build on Priestley’s discovery about plants and exposed for what they are. Research promptly returns to its fruitful tra- the restoration of air. -

Development of Preservice Biology Teachers‟ Skills in the Causal Process Concerning Photosynthesis

Journal of Education and Training Studies Vol. 7, No. 4; April 2019 ISSN 2324-805X E-ISSN 2324-8068 Published by Redfame Publishing URL: http://jets.redfame.com Development of Preservice Biology Teachers‟ Skills in the Causal Process Concerning Photosynthesis Arzu Saka Correspondence: Arzu Saka, Trabzon University, Fatih Faculty of Education, Trabzon, 61335,Turkey. Received: February 12, 2019 Accepted: March 7, 2019 Online Published: March 11, 2019 doi:10.11114/jets.v7i4.4022 URL: https://doi.org/10.11114/jets.v7i4.4022 Abstract Photosynthesis is the most effective cycle and sustainable natural process known in nature. Students who learn the subject of photosynthesis well will also make better sense of other issues such as environmental problems, the state of the atmosphere, greenhouse gases, climate changes, carbon footprints and conservation of forests. The aim of this study is to present an example of a worksheet that investigates the skill levels possessed by preservice teachers‟ in the causal process, and also to examine their ability to write a photosynthesis equation by means of a history-based approach that also includes reading skills. The study was conducted with the action research method. The study sample consisted of a total of 71 preservice biology teachers. At the first stage, before the implementation of the worksheet, 34 teacher candidates from within the sample were asked a question with a diagram summarising the photosynthesis process. At the second stage, all the prospective teachers were asked for the skill levels they possessed in the causal process to be assessed via implementation of the worksheet. The answers given by the preservice teachers in the defining variables section in particular make up the least answered section of the worksheet. -

Download Download

Early Modern Low Countries 1 (2017) 2, pp. 273-296 - eISSN: 2543-1587 273 The Banished Scholar Beverland, Sex, and Liberty in the Seventeenth-Century Low Countries Karen Hollewand Karen Hollewand completed her ba and ma at the University of Utrecht before moving to England, where she finished her dphil on the banishment of Beverland at the University of Oxford in 2016. She is interested in the early modern social, cultural, and intellectual history of Europe and of the Low Countries in particular. Currently, she is editing her thesis for publication, working on an English translation of Beverland’s De Peccato Originali with Floris Verhaart, and developing a new research project on sex and science in the early modern period. Abstract Scholar Hadriaan Beverland was banished from Holland in 1679. Why was this humanist exiled from one of the most tolerant parts of Europe in the seventeenth century? This arti- cle argues that it was Beverland’s singular focus on sexual lust that got him into such great trouble. In his studies, he highlighted the importance of sex in human nature, history, and his own society. Dutch theologians disliked his theology, exegesis, and his use of erudition to mock their authority. His humanist colleagues did not support him either, since Bev- erland threatened the basis of the humanist enterprise by drawing attention to the sexual side of the classical world. And Dutch magistrates were happy to convict the young scholar, because he had insolently accused them of hypocrisy. By restricting sex to marriage, in compliance with Reformed doctrine, secular authorities upheld a sexual morality that was unattainable, Beverland argued, and he proposed honest discussion of the problem of sex. -

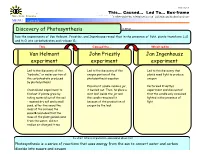

Discovery of Photosynthesis Jan Ingenhousz Experiment John

Cause / Effect TM This… Caused… Led To… Box-frame . Makes Sense Strategies © 2007 Edwin Ellis, All Rights© 2007 Reserved Edwin Published Ellis, byAll Makes Rights Sense Reserved Strategies, LLC, www.MakesSenseStrategies.com Lillian, AL www.MakesSenseStrategies.com MENU sample Name: Date: Discovery of Photosynthesis Is about … how the experiments of Van Helmont, Priestley, and Ingenhousz reveal that in the presence of light, plants transform C2O and H2O into carbohydrates and release O2. This Caused the… Which led to … Van Helmont John Priestly Jan Ingenhousz experiment experiment experiment · Led to the discovery of the · Led to the discovery of the · Led to the discovery that “hydrate,” or water portion of oxygen portion of the plants need light to produce the carbohydrate produced photosynthesis equation oxygen by photosynthesis · Placed a lit candle inside a jar, · Performed Priestly’s · Created and experiment to it burned out. Then, he place a experiment and discovered find out if plants grew by mint leaf inside the jar and that the candle only remained taking material out of the soil the candle remained lit lighted in the presence of – massed dry soil and a small because of the production of light seed, after five years the oxygen by the leaf mass of the soil was the sameèconcluded that the mass of the plant gained came from the water, did not realize air changed it too So what? What is important to understand about this? Photosynthesis is a series of reactions that uses energy from the sun to convert water and carbon dioxide into sugars and oxygen . -

A History of Uremia Research

ICURT PROCEEDINGS A History of Uremia Research Garabed Eknoyan, MD The history of uremia research begins with the discovery of urea and the subsequent association of elevated blood urea levels with the kidney disease described by Richard Bright, a well told story that needs no recounting. What this article highlights is how clinical and laboratory studies of urea launched the analysis of body fluids, first of urine and then of blood, that would beget organic chemistry, paved the way for the study of renal function and the use of urea clearance to determine ‘‘renal efficiency,’’ provided for the initial classification of kidney disease, and clarified the concepts of diffusion and osmosis that would lead to the development of dialysis. Importantly and in contrast to how the synthesis of urea in the laboratory heralded the death of ‘‘vitalism,’’ the clinical use of dialysis restored the ‘‘vitality’’ of comatose unresponsive dying uremic patients. The quest for uremic toxins that followed has made major contributions to what has been facetiously termed ‘‘molecular vitalism.’’ In the course of these major achievements derived from the study of urea, the meaning of ‘‘what is life’’ has been gradually liberated from its past attribution to supernatural forces (vital spirit, archaeus, and vital force) thereby estab- lishing the autonomy of biological life in which the kidney is the master chemist of the living body. Ó 2017 by the National Kidney Foundation, Inc. All rights reserved. HE HISTORY OF uremia research can be traced to supernatural forces that had been assumed for millennia T the Scientific Revolution when urea was discovered, past, and thereby established the autonomy of biological through the Enlightenment when it was isolated and char- life in which the kidney is the master chemist of the acterized, the early modern period when it was synthesized living body. -

Final Copy 2020 05 12 Leen

This electronic thesis or dissertation has been downloaded from Explore Bristol Research, http://research-information.bristol.ac.uk Author: Leendertz-Ford, Anna S T Title: Anatomy of Seventeenth-Century Alchemy and Chemistry General rights Access to the thesis is subject to the Creative Commons Attribution - NonCommercial-No Derivatives 4.0 International Public License. A copy of this may be found at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/legalcode This license sets out your rights and the restrictions that apply to your access to the thesis so it is important you read this before proceeding. Take down policy Some pages of this thesis may have been removed for copyright restrictions prior to having it been deposited in Explore Bristol Research. However, if you have discovered material within the thesis that you consider to be unlawful e.g. breaches of copyright (either yours or that of a third party) or any other law, including but not limited to those relating to patent, trademark, confidentiality, data protection, obscenity, defamation, libel, then please contact [email protected] and include the following information in your message: •Your contact details •Bibliographic details for the item, including a URL •An outline nature of the complaint Your claim will be investigated and, where appropriate, the item in question will be removed from public view as soon as possible. ANATOMY OF SEVENTEENTH-CENTURY ALCHEMY AND CHEMISTRY ANNA STELLA THEODORA LEENDERTZ-FORD A dissertation submitted to the University of Bristol in accordance with the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Faculty of Arts, School of Philosophy. -

Jean Senebier's Thoughts on Experimentation

| Jean Senebier’s thoughts on experimentation and their relevance for today’s researcher | 185 | Jean Senebier’s thoughts on experimentation and their relevance for today’s researcher Edward E. FARMER * Ms. received the 22nd April 2010, accepted the 10th September 2010 T Abstract How are observation and experimentation related to one another? Jean Senebier (1742-1809) tackled this question in his philosophical works on The Art of Observing. However, Senebier was not only a theoretician and, not long after his first publications on observation, his own experiments contributed to resolve a major question in biology: what do the leaves of plants feed on? By analysing Senebier’s works on science theory in parallel with those reporting his scientific discoveries, this article shows that The Art of Observing series is not restricted to observation and contains deep insights into the process of experimenting with living organisms. Keywords: Senebier, plant physiology, photosynthesis, science didactics, epistemology T Résumé Les considérations de Jean Senebier sur l’expérimentation et leur intérêt pour les chercheurs d’aujourd’hui. – Quel est le lien entre l’observation et l’expérimentation? Jean Senebier (1742-1809) a abordé cette question dans sa série d’ouvrages sur l’Art d’observer. Cependant, Senebier n’était pas seulement un théoricien et, peu après ses premières publi - cations sur l’observation, il a commencé à travailler sur l’une des grandes questions de la biologie: « de quoi se nourrissent les feuilles des plantes? » S’appuyant sur ce qu’il avait appris en tant qu’expérimentaliste, Senebier a par la suite été en mesure d’approfondir ses brillantes analyses présentées dans ses deux premières publications sur l’Art d’observer. -

Francis Bacon, Jan Baptist Van Helmont and Demetrius Cantemir

SWEDISH JOURNAL OF ROMANIAN STUDIES FRANCIS BACON, JAN BAPTIST VAN HELMONT AND DEMETRIUS CANTEMIR. FAMILY RESEMBLANCES OF AUCTORITAS IN EARLY MODERN EUROPE Sorin CIUTACU West University of Timisoara, Romania e-mail: [email protected] Abstract: The present paper stakes out the destiny of certain ideas on scientific methods and epistemic and ontological representations that spread in 17th century Europe like a cultural epidemiology of representations against a deist, theosophical, empiricist and occult maze-like background. Our intellectual history study evaluates the family resemblances of auctoritas of three polymaths: Francis Bacon, Jan Baptist Van Helmont and Demetrius Cantemir along the cultural corridors of knowledge. If Francis Bacon was a theoretical founder of doctrines and Jan Baptist Van Helmont was a complex experimenting spirit, Demetrius Cantemir was an able disseminator of philosophy in South Eastern Europe and a creative synthetic spirit bridging the Divan ideas of Western and Eastern minds caught up in the busy exchange of ideas of the Republic of Letters. Keywords: Francis Bacon; Jan Baptist Van Helmont; Demetrius Cantemir; cultural epidemiology of representations; auctoritas; family resemblances; Early Modern Europe; polymaths; corridors of knowledge; Republic of Letters; 1. Introduction The 17th century stood for a transition period between an ontological outlook of vitalism that typified Renaissance thinking through to the early modern outlook of Francis Bacon, the founder of the scientific method to the mechanistic thinking put forward by Descartes and Newton. The present paper stakes out the destiny of certain ideas on scientific methods and epistemic and ontological representations that spread in 17th century Europe like a cultural epidemiology of representations against a deist, theosophical, empiricist and occult maze-like background (see also Sperber, 1996). -

Daily 40 No. 6 – Johann Baptista Van Helmont

Daily 40 no. 6 – Johann Baptista van Helmont Daily 40 Hall of Fame! Congratulations to these writers! Van Helmont, a iatrochemist, was born 1579 in Belgium. He believed that matter was indestructible, and checked if his products were equal to his reactants. Van Helmont is regarded as the father of pneumatic chemistry and recognized the existence of gases different from the surrounding air. --Andrew Johann Baptista van Helmont of Belgium (1579-1644) signified the transition from alchemy to chemistry. While he claimed to have converted mercury to gold, he studied gases using experimental methods and balances, discovered carbon dioxide, and, upon carefully measuring a tree’s growth for five years, realized that matter is indestructible. --Chantal Johann Baptista van Helmont, born in 1579 in Belgium, represented the transformation between alchemy and chemistry and also recognized and characterized gases. He discovered carbon dioxide and was the first to use a balance in chemical work. He rejected Aristotle's four elements but supported air and water as foundational elements. --Gennelle Johann Baptista van Helmont was a Flemish iatrochemist who lived from 1579-1644 and founded pneumatic chemistry. He discovered that matter cannot be destroyed or created. Helmont regarded air and water as elements but he did not see earth and fire as elements. His greatest legacy is inventing the word gas. --Isaac Johann Baptista van Helmont(1579-1644) was a Flemish chemist who believed that matter was indestructible. He was interested in alchemy mainly for medicinal purposes. He tried to burn charcoal and capture the gases, which he called “spiritus silvestri, or “breath of wood.” His work heralded the transition from alchemy to chemistry. -

Photosynthesis Photosynthesis

Unit 5 Photosynthesis UNIT 5 PHOTOSYNTHESIS Structure 5.1 Introduction 5.4 Role of Sunlight Objectives Electromagnetic Spectrum 5.2 Basic Concepts – Historical Absorption and Action Background Spectrum Earlier Investigations Absorption of Photons – Energy States of Chlorophyll Development of Concept – Formulation of Equation of 5.5 Summary Photosynthesis 5.6 Terminal Questions 5.3 Photosynthetic Pigments 5.7 Answers Essential Pigments : Chlorophylls Accessory Pigments Non-Photosynthetic Pigments and Photoreceptors 5.1 INTRODUCTION In this Unit you will be studying the plant pigments including non- photosynthetic pigments and sunlight, which are required for photosynthesis— a process by which green plants and certain other organisms transform light energy into chemical energy in the form of sugars. This sugar can then be converted to other carbohydrates or other food materials like fats and proteins. The general importance of the process was recognized as long ago as 2000 years. The biblical saint, Isaiah, who lived between 700-600 B.C. said “All flesh is grass” recognizing that all food chains are finally traced to plants. Plants are also responsible for the fossil fuels such as petroleum, oil, and coal, which represent products of photosynthesis carried out millions of years ago in the carboniferous era. It is through this process that plants continuously purify air during daytime and thus allow animals to breathe. The overall importance of this process is best expressed in the words of Eugene Rabinowitch, one of the great authors and