Full Draft Munir Mohammad 080718

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

VIEWED from the OTHER SIDE: Media Coverage and Personal Tales of Migration in Iraqi Kurdistan

VIEWED FROM THE OTHER SIDE: Media Coverage and Personal Tales of Migration in Iraqi Kurdistan Kjersti Thorbjørnsrud, Espen Gran, Mohammed A. Salih, Sareng Aziz Viewed from the other Side: Media Coverage and Personal Tales of Migration in Iraqi Kurdistan Kjersti Thorbjørnsrud, Espen Gran, Mohammed A. Salih and Sareng Aziz IMK Report 2012 Department of Media and Communication Faculty of Humanities University of Oslo Viewed from the other side: Media Coverage and Personal Tales of Migration in Iraqi Kurdistan Contents Acknowledgements ............................................................................................................ III Abbreviations..................................................................................................................... IV Executive summary ............................................................................................................. V The coverage of migration in Iraqi Kurdistan ....................................................................VI Why certain frames and stories dominate in the news – findings from elite interviews .... VII The main motivations of migration in Iraqi Kurdistan .......................................................IX The experiences of those who have returned from Europe – expectations and disappointments ................................................................................................................IX Knowledge and evaluation of European immigration and return policies ............................ X Main conclusions .............................................................................................................. -

Gericht Entscheidungsdatum Geschäftszahl Spruch Text

08.11.2019 Gericht BVwG Entscheidungsdatum 08.11.2019 Geschäftszahl I415 2224340-1 Spruch I415 2224340-1/5E IM NAMEN DER REPUBLIK! Das Bundesverwaltungsgericht hat durch den Richter Mag. Hannes LÄSSER über die Beschwerde von XXXX, geb. XXXX, Staatsangehörigkeit Irak, gesetzlich vertreten durch die Mutter XXXX, geb. XXXX, diese vertreten durch Diakonie Flüchtlingsdienst gemeinnützige GmbH und Volkshilfe Flüchtlings- und MigrantInnenbetreuung GmbH als Mitglieder der ARGE Rechtsberatung - Diakonie und Volkshilfe und den MigrantInnenverein St. Marx, gegen den Bescheid des Bundesamtes für Fremdenwesen und Asyl vom 09.09.2019, Zl. XXXX, zu Recht erkannt: A) Die Beschwerde wird als unbegründet abgewiesen. B) Die Revision ist gemäß Art. 133 Abs. 4 B-VG nicht zulässig. Text ENTSCHEIDUNGSGRÜNDE: I. Verfahrensgang: Die Eltern des minderjährigen Beschwerdeführers und zwei minderjährige Brüder und die minderjährige Schwester des Beschwerdeführers stellten am 31.12.2015 nach ihrer schlepperunterstützten unrechtmäßigen Einreise in das Bundesgebiet vor einem Organ des öffentlichen Sicherheitsdienstes einen Antrag auf internationalen Schutz. Die Genannten sind Staatsangehörige des Irak und gehören der kurdischen Volksgruppe an. Im Rahmen der niederschriftlichen Erstbefragung vor Organen des öffentlichen Sicherheitsdienstes der Polizeiinspektion XXXX am Tag der Antragstellung legte der Vater des Beschwerdeführers dar, den Namen XXXX zu führen. Er sei am XXXX1985 in XXXX geboren, Angehöriger der kurdischen Volksgruppe und bekenne sich zum Islam. Zuletzt habe er in Erbil gelebt und als Hilfsarbeiter gearbeitet. Im Hinblick auf den Reiseweg brachte der Vater des Beschwerdeführers zusammengefasst vor, den Irak am 10.12.2015 mit der Mutter des Beschwerdeführers und den gemeinsamen Kindern legal von Erbil ausgehend auf dem Landweg in die Türkei verlassen zu haben. -

Kurdistan Rising? Considerations for Kurds, Their Neighbors, and the Region

KURDISTAN RISING? CONSIDERATIONS FOR KURDS, THEIR NEIGHBORS, AND THE REGION Michael Rubin AMERICAN ENTERPRISE INSTITUTE Kurdistan Rising? Considerations for Kurds, Their Neighbors, and the Region Michael Rubin June 2016 American Enterprise Institute © 2016 by the American Enterprise Institute. All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be used or reproduced in any man- ner whatsoever without permission in writing from the American Enterprise Institute except in the case of brief quotations embodied in news articles, critical articles, or reviews. The views expressed in the publications of the American Enterprise Institute are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the staff, advisory panels, officers, or trustees of AEI. American Enterprise Institute 1150 17th St. NW Washington, DC 20036 www.aei.org. Cover image: Grand Millennium Sualimani Hotel in Sulaymaniyah, Kurdistan, by Diyar Muhammed, Wikimedia Commons, Creative Commons. Contents Executive Summary 1 1. Who Are the Kurds? 5 2. Is This Kurdistan’s Moment? 19 3. What Do the Kurds Want? 27 4. What Form of Government Will Kurdistan Embrace? 56 5. Would Kurdistan Have a Viable Economy? 64 6. Would Kurdistan Be a State of Law? 91 7. What Services Would Kurdistan Provide Its Citizens? 101 8. Could Kurdistan Defend Itself Militarily and Diplomatically? 107 9. Does the United States Have a Coherent Kurdistan Policy? 119 Notes 125 Acknowledgments 137 About the Author 139 iii Executive Summary wo decades ago, most US officials would have been hard-pressed Tto place Kurdistan on a map, let alone consider Kurds as allies. Today, Kurds have largely won over Washington. -

Gunmen Seize 43 UN Peacekeepers

Kuwaiti man Iraq, Syria pose Arsenal in reportedly Saudi dilemma; 17th straight jailed by failed states or Champions Islamic State8 Iranís12 proxies group47 stage Max 45º Min 29º FREE www.kuwaittimes.net NO: 16269- Friday, August 29, 2014 Gunmen seize 43 UN peacekeepers Page 10 SYRIA: An armoured ambulance of the United Nations Disengagement Observer Force (UNDOF) waits next to other UN vehicles in the Israeli-annexed Golan Heights as they wait to cross into the Syrian side of the Golan, yesterday. The United Nations confirmed that an armed group captured 43 UN peacekeepers on the Syrian side of the Golan Heights yesterday, saying it was doing everything to secure their release. — AFP Local FRIDAY, AUGUST 29, 2014 In my view Alcoholism in Kuwait By By Sara Ahmed KUWAIT: A woman participates in a weaving course at Sadu House. [email protected] lcohol is illegal in Kuwait and because of this, there is little to no discussion about alcoholism, Aits impact on the individual, the family or socie- ty. Yet alcoholism cuts across all social, nationality, economic and racial barriers. It can also be found in many homes in Kuwait and security forces regularly arrest smugglers or home brewers. Setting aside the illegality of the matter, however, the question of alco- holism is seldom addressed for several reasons. First, given that alcohol is illegal, it’s a closed subject. How can someone seek treatment for alcoholism when they are not supposed to be drinking in the first place? Many would fear legal action or criminal charges for possession or consumption. -

Iraq 2017 Human Rights Report

IRAQ 2017 HUMAN RIGHTS REPORT EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Iraq is a constitutional parliamentary republic. The outcome of the 2014 parliamentary elections generally met international standards of free and fair elections and led to the peaceful transition of power from former prime minister Nuri al-Maliki to Prime Minister Haider al-Abadi. Civilian authorities were not always able to exercise control of all security forces, particularly certain units of the Popular Mobilization Forces (PMF) that were aligned with Iran. Violence continued throughout the year, largely fueled by the actions of the Islamic State in Iraq and Syria (ISIS). Government forces successfully fought to liberate territory taken earlier by ISIS, including Mosul, while ISIS sought to demonstrate its viability through targeted attacks. Armed clashes between ISIS and government forces caused civilian deaths and hardship. By year’s end Iraqi Security Forces (ISF) had liberated all territory from ISIS, drastically reducing ISIS’s ability to commit abuses and atrocities. The most significant human rights issues included allegations of unlawful killings by some members of the ISF, particularly some elements of the PMF; disappearance and extortion by PMF elements; torture; harsh and life-threatening conditions in detention and prison facilities; arbitrary arrest and detention; arbitrary interference with privacy; criminalization of libel and other limits on freedom of expression, including press freedoms; violence against journalists; widespread official corruption; greatly reduced penalties for so-called “honor killings”; coerced or forced abortions imposed by ISIS on its victims; legal restrictions on freedom of movement of women; and trafficking in persons. Militant groups killed LGBTI persons. There were also limitations on worker rights, including restrictions on formation of independent unions. -

Foreign Satellite & Satellite Systems Europe Africa & Middle East Asia

Foreign Satellite & Satellite Systems Europe Africa & Middle East Albania, Austria, Belarus, Belgium, Bosnia & Algeria, Angola, Benin, Burkina Faso, Cameroon, Herzegonia, Bulgaria, Croatia, Czech Republic, Congo Brazzaville, Congo Kinshasa, Egypt, France, Germany, Gibraltar, Greece, Hungary, Ethiopia, Gabon, Ghana, Ivory Coast, Kenya, Iceland, Ireland, Italy, Luxembourg, Macedonia, Libya, Mali, Mauritania, Mauritius, Morocco, Moldova, Montenegro, The Netherlands, Norway, Mozambique, Namibia, Niger, Nigeria, Senegal, Poland, Portugal, Romania, Russia, Serbia, Somalia, South Africa, Sudan, Tanzania, Tunisia, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain, Sweden, Switzerland, Uganda, Western Sahara, Zambia. Armenia, Ukraine, United Kingdom. Azerbaijan, Bahrain, Cyprus, Georgia, Iran, Iraq, Israel, Jordan, Kuwait, Lebanon, Oman, Palestine, Qatar, Saudi Arabia, Syria, Turkey, United Arab Emirates, Yemen. Asia & Pacific North & South America Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, Cambodia, Canada, Costa Rica, Cuba, Dominican Republic, China, Hong Kong, India, Japan, Kazakhstan, Honduras, Jamaica, Mexico, Puerto Rico, United Kyrgyzstan, Laos, Macau, Maldives, Myanmar, States of America. Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Nepal, Pakistan, Phillipines, South Korea, Chile, Columbia, Ecuador, Paraguay, Peru, Sri Lanka, Taiwan, Tajikistan, Thailand, Uruguay, Venezuela. Uzbekistan, Vietnam. Australia, French Polynesia, New Zealand. EUROPE Albania Austria Belarus Belgium Bosnia & Herzegovina Bulgaria Croatia Czech Republic France Germany Gibraltar Greece Hungary Iceland Ireland Italy -

Iraqi Kurds Go to the Polls: Is Change Possible? | the Washington Institute

MENU Policy Analysis / PolicyWatch 1556 Iraqi Kurds Go to the Polls: Is Change Possible? by J. Scott Carpenter, Ahmed Ali Jul 23, 2009 ABOUT THE AUTHORS J. Scott Carpenter J. Scott Carpenter is an adjunct fellow at the Washington Institute for Near East Policy. Ahmed Ali Ahmed Ali is a program officer at the National Endowment for Democracy. Brief Analysis n July 25, Iraqi Kurds go to the polls to vote in a joint parliamentary and presidential election. Although a O heated competition in January produced massive change at the provincial level throughout the rest of Iraq, the electoral system produced by the incumbent Iraqi Kurdistan parliament prevents such sweeping changes in the north. Both the current coalition governing the Kurdish Regional Government (KRG) and the current KRG president, Masoud Barzani, will most likely be reelected. Despite the lack of change, the postelection period will create an opportunity for Baghdad, Washington, and the KRG to resolve outstanding issues that cause increased tension between Arabs and Kurds. Resolution can occur only if all parties take advantage of new political openings, however narrow. Impact of the Electoral Law The KRG's 2009 amended election law combines the three provinces of Iraqi Kurdistan into a single district and presents a closed-list system that requires voters to select only lists, not candidates. This electoral system maximizes support for well-organized, well-disciplined parties; additionally, it prevents independent groups from gaining significant electoral ground, since would-be challengers to the establishment have to field candidates across the entire Kurdish region, even if they are only strong in certain areas. -

RTL Nederland and Spotxchange Have Announced a Joint Venture for the Benelux & Nordic Region

week 13 / 26 March 2015 MISSION: DIGITAL RTL Nederland and SpotXchange have announced a joint venture for the Benelux & Nordic region France The Netherlands Germany Renewal of Groupe M6’s RTL Ventures invests Clipfish launches Supervisory Board in Reclamefolder.nl on Amazon Fire TV week 13 / 26 March 2015 MISSION: DIGITAL RTL Nederland and SpotXchange have announced a joint venture for the Benelux & Nordic region France The Netherlands Germany Renewal of Groupe M6’s RTL Ventures invests Clipfish launches Supervisory Board in Reclamefolder.nl on Amazon Fire TV Cover From left to right: Elwin Gastelaars, Managing Director SpotXchange Benelux, Arno Otto, Managing Director Digital RTL Nederland, Ton Rozestraten, Chief Commercial Officer RTL Nederland, Mike Shehan, CEO SpotXchange Bert Habets, CEO RTL Nederland, Erik Swain, Senior Vice President Operations SpotXchange Publisher RTL Group 45, Bd Pierre Frieden L-1543 Luxembourg Editor, Design, Production RTL Group Corporate Communications & Marketing k before y hin ou T p r in t backstage.rtlgroup.com backstage.rtlgroup.fr backstage.rtlgroup.de QUICK VIEW Renewal of Groupe M6’s Supervisory Board Groupe M6 / RTL Group p.9–10 CSI meets Mad Men RTL Nederland / SpotXchange RTL Ventures invests p.4–8 in Reclamefolder.nl RTL Nederland p.11–12 Clipfish launches on Amazon Fire TV RTL Interactive p.13 Enex on solid growth path Enex Big Picture p.14 p.16 20 years of SHORT Pop-Rock sound RTL 2 NEWS p.15 p.17–18 RTL2 FÊTE SES 20 ANS ! PEOPLE RTL2, LA Radio du son POP-ROCK a 20 ANS, l’occasion de fêter cet évènement avec ses auditeurs, qui n’ont jamais été aussi p.19nombreux depuis sa création avec 2 830 000 auditeurs chaque jour. -

6. Kurdistan Region of Iraq (KRI)

Country Policy and Information Note Iraq: Political opinion in the Kurdistan Region of Iraq (KRI) Version 1.0 August 2017 Preface This note provides country of origin information (COI) and policy guidance to Home Office decision makers on handling particular types of protection and human rights claims. This includes whether claims are likely to justify the granting of asylum, humanitarian protection or discretionary leave and whether – in the event of a claim being refused – it is likely to be certifiable as ‘clearly unfounded’ under s94 of the Nationality, Immigration and Asylum Act 2002. Decision makers must consider claims on an individual basis, taking into account the case specific facts and all relevant evidence, including: the policy guidance contained with this note; the available COI; any applicable caselaw; and the Home Office casework guidance in relation to relevant policies. Country Information COI in this note has been researched in accordance with principles set out in the Common EU [European Union] Guidelines for Processing Country of Origin Information (COI) and the European Asylum Support Office’s research guidelines, Country of Origin Information report methodology, namely taking into account its relevance, reliability, accuracy, objectivity, currency, transparency and traceability. All information is carefully selected from generally reliable, publicly accessible sources or is information that can be made publicly available. Full publication details of supporting documentation are provided in footnotes. Multiple sourcing is normally used to ensure that the information is accurate, balanced and corroborated, and that a comprehensive and up-to-date picture at the time of publication is provided. Information is compared and contrasted, whenever possible, to provide a range of views and opinions. -

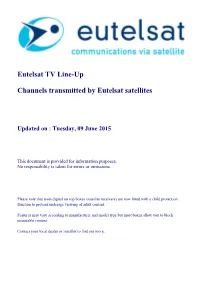

Linup Report

Eutelsat TV Line-Up Channels transmitted by Eutelsat satellites Updated on : Tuesday, 09 June 2015 This document is provided for information purposes. No responsibility is taken for errors or omissions. Please note that most digital set top boxes (satellite receivers) are now fitted with a child protection function to prevent underage viewing of adult content. Features may vary according to manufacturer and model type but most boxes allow you to block unsuitable content. Contact your local dealer or installer to find out more. Freq Beam Analo Diff Fec Symb Acces Lang g ol Rate EUTELSAT 117 WEST A 3.720 V C Edusat package DVB-S 3/4 27.000 C Telesecundaria TV DVB-S 3/4 27.000 Spanish C TV Docencia TV DVB-S 3/4 27.000 Spanish C ILCE Canal 13 TV DVB-S 3/4 27.000 Spanish C UnAD TV DVB-S 3/4 27.000 Spanish C ILCE Canal 15 TV DVB-S 3/4 27.000 Spanish C Canal 22 Nacional TV DVB-S 3/4 27.000 Spanish C Telebachillerato TV DVB-S 3/4 27.000 Spanish C ILCE Canal 18 TV DVB-S 3/4 27.000 Spanish C Tele México TV DVB-S 3/4 27.000 Spanish C TV Universidad TV DVB-S 3/4 27.000 Spanish C Red de las Artes TV DVB-S 3/4 27.000 Spanish C Aprende TV DVB-S 3/4 27.000 Spanish C Canal del Congreso TV DVB-S 3/4 27.000 Spanish C Especiales TV DVB-S 3/4 27.000 Spanish C Transmisiones Especiales 27 TV DVB-S 3/4 27.000 Spanish C TV UNAM TV DVB-S 3/4 27.000 Spanish 3.744 V C INE TV TV DVB-S2 3/4 2.665 Spanish 3.748 V C Radio Centro radio DVB-S 7/8 2.100 Spanish 3.768 V C Inti Network TV DVB-S2 3/4 4.800 Spanish 3.772 V C Gama TV TV DVB-S 3/4 3.515 BISS Spanish 3.786 V -

Kurdistan Regional Government

Received by NSD/FARA Registration Unit 05/05/2021 12:48:24 PM Subject: Commemorating the 30th anniversary of Operation Provide Comfort - Final Speaker Lis From: Kurdistan Regional Government - USA <[email protected]> To: [email protected] Date Sent: Tuesday April 27, 2021 12:05:10 PM GMT-04:00 Date Received: Tuesday April 27, 2021 12:45:22 PM GMT-04:00 Kurdistan Regional Government Representation in the United States Washington D.C. Final Speaker List The Turning Point: Operation Provide Comfort Commemorating the 30th anniversary of the US-led humanitarian mission - B m & / 3* The Turning Point: Operation Provide Comfort Commemorating the 30th anniversary of the US-led humanitarian mission When Tomorrow, April 28, 10 am EST / 5 pm Erbil Time 1/3 Received by NSD/FARA Registration Unit 05/05/2021 12:48:24 PM Received by NSD/FARA Registration Unit 05/05/2021 12:48:24 PM Where Virtual Event Register This month marks the 30th anniversary of a remarkable humanitarian action, known as Operation Provide Comfort, led by the United States, the UK and France, which saved hundreds of thousands of Kurds who had fled the genocidal actions of Saddam Hussein in 1991. Following the Kurdish uprising against the dictator in March 1991, Hussein used his helicopter gunships and tanks to attack the people who had risen up against his regime. Fearing that Hussein would use chemical weapons again, up to 2 million Kurds fled to border mountains of Turkey and Iran, where they were stranded, facing death from exposure to the elements, malnutrition and disease. -

FM Forts of Various State Agencies

BUSINESS | Page 1 SPORT | Page 1 El Arabi puts Duhail on top, INDEX DOW JONES QE NYMEX QATAR 2-8, 24 COMMENT 22, 23 Ooredoo to showcase Gharafa REGION 9 BUSINESS 1-14, 20-24 25,177.00 9,106.77 62.50 ARAB WORLD 9 CLASSIFIED 15-19 tech solutions at the -59.00 +27.34 +0.82 INTERNATIONAL 10-21 SPORTS 1-7 also win -0.23% +0.30% +1.33% Mobile World Congress Latest Figures published in QATAR since 1978 TUESDAY Vol. XXXVIII No. 10735 February 20, 2018 Jumada II 4, 1439 AH GULF TIMES www. gulf-times.com 2 Riyals Emir gets Sudanese president’s message Road deaths In brief and injuries QATAR | Reaction Church shooting in Russia condemned Qatar strongly condemned the fall in Qatar shooting that targeted a church in Russia’s southern province of oad deaths and injuries in Qatar arrival time at accident spots from 15 Dagestan, which caused a number declined in 2017 compared to minutes to around 5-7 minutes. The of deaths and injuries. In a statement R2016, the General Directorate of new driving test strategy and curricu- yesterday, Qatar’s Ministry of Foreign Traffi c announced yesterday. lum focuses on producing high quality Aff airs reiterated Qatar’s firm position “Only 5.4 road traffi c accident (RTA) drivers, equipped with proper traffi c rejecting violence and terrorism deaths per 100,000 persons were re- awareness. regardless of motives and reasons. It corded in the country last year, com- The use of more speed radars and expressed Qatar’s condolences to the His Highness the Emir Sheikh Tamim bin Hamad al-Thani has received a written message from Sudanese President Omar Hassan pared to the world average of 17.4,” surveillance cameras across greater families of the victims, the government al-Bashir, pertaining to the bilateral relations and ways to enhance them.