One Buddha Can Hide Another

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Inventaire-CIK-09042017.Pdf

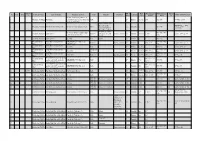

Autre(s) Nb de Date Estampages Estampages Autres K. Ext. Ind. Pays, province Lieu d’origine Situation actuelle Type Détails Matériau Langue Éditions/traductions n° lignes (śaka) EFEO BNF est. In situ ; dans la maçonnerie de 1 - - - Vietnam, An Giang Vat Thling l’autel de la pagode du village de Stèle 26 Khmer vie-viie 271 302 (34) - IC VI, p. 28-30 Lê Hoat, Châu Đốc Dalle formant seuil du tombeau du BEFEO XL, p. 480 2 - - - Vietnam, An Giang Phnom Svam ou Nui Sam In situ (en 1923, Cœdès 1923) Dalle 12 Sanskrit xe - 301 (34) - mandarin Nguyên (chronique) Ngoc Thoai ; Ruinée Trouvée sur l'allée In situ (en 2002), enchassé dans 303 (34) ; 471 3 - - - Vietnam, An Giang Linh Son Tu Piédroit principale de Linh Schiste ardoisier 11 Sanskrit vie-viie n. 295 - Cœdès 1936, p. 7-9 l'autel de Linh Son Tu (79) Son Tu 4 - - - Vietnam, An Giang Linh Son Tu Inconnue Stèle Ruinée 12 Khmer xe - 304 (34) - - Vietnam, Đồng Thap Muoi, Prasat Pram BTLSHCM 2893 (Kp 1, 2) ; 305 (69) ; 472 5 - - - Piédroit Schiste ardoisier 22 Sanskrit ve 329 ; n. 15 - Cœdès 1931, p. 1-7 Tháp Loveng BTLS 5964? (79) Vietnam, Đồng Thap Muoi, Prasat Pram 6 - - - Inconnue Stèle 10 Khmer vie-viie - 306 (34) - Cœdès 1936, p. 5 Tháp Loveng Vietnam, Đồng Thap Muoi, Prasat Pram Chapiteau 307 (34) ; 473 7 - - - Inconnue 20 Khmer vie-viie 331 ; n. 16 - Cœdès 1936, p. 3-5 Tháp Loveng (?) (79) Vietnam, Đồng Thap Muoi, Prasat Pram 308 (34) ; 474 8 - - - DCA 6811 Piédroit Schiste ardoisier 10 Khmer vie-viie 259 ; n. -

Cambodia-10-Contents.Pdf

©Lonely Planet Publications Pty Ltd Cambodia Temples of Angkor p129 ^# ^# Siem Reap p93 Northwestern Eastern Cambodia Cambodia p270 p228 #_ Phnom Penh p36 South Coast p172 THIS EDITION WRITTEN AND RESEARCHED BY Nick Ray, Jessica Lee PLAN YOUR TRIP ON THE ROAD Welcome to Cambodia . 4 PHNOM PENH . 36 TEMPLES OF Cambodia Map . 6 Sights . 40 ANGKOR . 129 Cambodia’s Top 10 . 8 Activities . 50 Angkor Wat . 144 Need to Know . 14 Courses . 55 Angkor Thom . 148 Bayon 149 If You Like… . 16 Tours . 55 .. Sleeping . 56 Baphuon 154 Month by Month . 18 . Eating . 62 Royal Enclosure & Itineraries . 20 Drinking & Nightlife . 73 Phimeanakas . 154 Off the Beaten Track . 26 Entertainment . 76 Preah Palilay . 154 Outdoor Adventures . 28 Shopping . 78 Tep Pranam . 155 Preah Pithu 155 Regions at a Glance . 33 Around Phnom Penh . 88 . Koh Dach 88 Terrace of the . Leper King 155 Udong 88 . Terrace of Elephants 155 Tonlé Bati 90 . .. Kleangs & Prasat Phnom Tamao Wildlife Suor Prat 155 Rescue Centre . 90 . Around Angkor Thom . 156 Phnom Chisor 91 . Baksei Chamkrong 156 . CHRISTOPHER GROENHOUT / GETTY IMAGES © IMAGES GETTY / GROENHOUT CHRISTOPHER Kirirom National Park . 91 Phnom Bakheng. 156 SIEM REAP . 93 Chau Say Tevoda . 157 Thommanon 157 Sights . 95 . Spean Thmor 157 Activities . 99 .. Ta Keo 158 Courses . 101 . Ta Nei 158 Tours . 102 . Ta Prohm 158 Sleeping . 103 . Banteay Kdei Eating . 107 & Sra Srang . 159 Drinking & Nightlife . 115 Prasat Kravan . 159 PSAR THMEI P79, Entertainment . 117. Preah Khan 160 PHNOM PENH . Shopping . 118 Preah Neak Poan . 161 Around Siem Reap . 124 Ta Som 162 . TIM HUGHES / GETTY IMAGES © IMAGES GETTY / HUGHES TIM Banteay Srei District . -

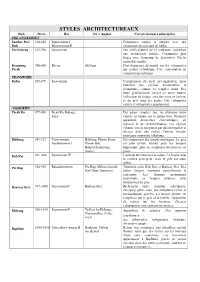

Styles Architectureaux

STYLES ARCHITECTUREAUX Style Dates Roi Où à Angkor Caractéristiques principales PRE-ANGKORIEN Sambor Prei 610-650 Isanavarman I, Colonnettes rondes et simples avec des Kuk Bhavavarman II chapiteaux incorporant un bulbe. Prei Kmeng 635-700 Jayavarman Des chefs-d'œuvre de la sculpture, cependant une architecture limitée. Colonnettes plus larges avec beaucoup de décoration. Déclin général de qualité Kompong 700-800 Divers AkYum Plus d'anneaux décoratifs sur les colonnettes Preah qui restent cylindrique. Une continuation de construction en brique TRANSITOIRE Kulen 825-875 Jayavarman Continuation du style pré-angkorien, mais toutefois une période d'innovation et d'emprunts, comme les temples cham. Des tours généralement carrées et assez hautes. Utilisation de brique, avec des murs en latérite, et du grès pour les portes. Des colonnettes carrées et octogonales apparaissent. ANGKORIEN Preah Ko 877-886 Preah Ko, Bakong, Des plans simples: une ou plusieurs tours Lolei carrées en brique sur la même base. Première apparition d'enceintes concentriques, de gopuras et de «bibliothèques». Les «palais volants» ont été remplacés par des dvarapalas et devatas dans des niches. Premier temple- montagne important à Bakong. Bakheng 889-923 Yasovarman I, Bakheng, Phnom Krom, Développement des temple-montagnes. Le grès Harshavarman I Phnom Bok, est plus utilisé, surtout pour les temples Baksei Chamkrong importants; plus de sculptures décoratives en (trans.) pierre. Koh Ker 921 -944 Jayavarman IV L'échelle diminue vers le centre. La brique reste la matière principale, mais le grès est aussi utilisé. Prè Rup 944-968 Râjendravarman Prè Rup, Mébon oriental, Transition entre Koh Ker et Banteay Srei. Des Bat Chum, Kutisvara halles longues entourent partiellement le sanctuaire. -

Destination: Angkor Archaeological Park the Complete Temple Guide

Destination: Angkor Archaeological Park The Complete Temple Guide 1 The Temples of Angkor Ak Yom The earliest elements of this small brick and sandstone temple date from the pre-Angkorian 8th century. Scholars believe that the inscriptions indicate that the temple is dedicated to the Hindu 'god of the depths'. This is the earliest known example of the architectural design of the 'temple-mountain', which was to become the primary design for many of the Angkorian period temples including Angkor Wat. The temple is in a very poor condition. Angkor Thom Angkor Thom ("Great City") was the last and most enduring capital city of the Khmer empire. It was established in the late 12th century by King Jayavarman VII. The walled and moated royal city covers an area of 9 km², within which are located several monuments from earlier eras as well as those established by Jayavarman and his successors. At the centre of the city is Jayavarman's state temple, the Bayon, with the other major sites clustered around the Victory Square immediately to the north. Angkor Thom was established as the capital of Jayavarman VII's empire, and was the centre of his massive building programme. One inscription found in the city refers to Jayavarman as the groom and the city as his bride. Angkor Thom is accessible through 5 gates, one for each cardinal point, and the victory gate leading to the Royal Palace area. Angkor Wat Angkor Wat ("City of Temples"), the largest religious monument in the world, is a masterpiece of ancient architecture. The temple was built by the Khmer King Suryavarman II in the early 12th century as his state temple and eventual mausoleum. -

Includes the Bayon, Angkor Thom, Siem Reap & Roluos Pdf, Epub, Ebook

ANGKOR: INCLUDES THE BAYON, ANGKOR THOM, SIEM REAP & ROLUOS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Andrew Spooner | 104 pages | 07 Jul 2015 | Footprint Travel Guides | 9781910120224 | English | Bath, United Kingdom Angkor: Includes the Bayon, Angkor Thom, Siem Reap & Roluos PDF Book Suppose one day you woke up from a dream of wanting to visit one of the most magnificent temples in the world. As I mentioned other Khmer temples in the World heritage list, Vat Phou and Preah Vihear or even Phanomroong in the tentative list of Thailand are very inferior when compared with Angkor, if you see Angkor before you may have negative view on those sites, as I had one with Vat Phou after I saw Preah Vihear, so to avoid the problem and be more appreciated in Khmer art development, try to keep Angkor at the end of your trip, a highly recommendation. Bus ban at Angkor Wat Superior food and accomodations in the area. It was originally built as an Hindu temple to be later slowly converted into a Buddhist temple. Replica in Legoland : Legoland Malaysia. Its a huge area with a host of great temples, some smaller, some bigger, but all unique and incredible. Breaking with the tradition of the Khmer kings, and influenced perhaps by the concurrent rise of Vaisnavism in India, he dedicated the temple to Vishnu rather than to Siva. Retrieved In , Yasovarman ascended to the throne. Log into your account. Log into your account. Angkor Wat is an outstanding example of Khmer architecture, the so-called Angkor Wat style, for obvious reasons. If you do not have this information now, please contact the local activity operator 24 hours prior to the start of the tour with these details. -

A STUDY of the NAMES of MONUMENTS in ANGKOR (Cambodia)

A STUDY OF THE NAMES OF MONUMENTS IN ANGKOR (Cambodia) NHIM Sotheavin Sophia Asia Center for Research and Human Development, Sophia University Introduction This article aims at clarifying the concept of Khmer culture by specifically explaining the meanings of the names of the monuments in Angkor, names that have existed within the Khmer cultural community.1 Many works on Angkor history have been researched in different fields, such as the evolution of arts and architecture, through a systematic analysis of monuments and archaeological excavation analysis, and the most crucial are based on Cambodian epigraphy. My work however is meant to shed light on Angkor cultural history by studying the names of the monuments, and I intend to do so by searching for the original names that are found in ancient and middle period inscriptions, as well as those appearing in the oral tradition. This study also seeks to undertake a thorough verification of the condition and shape of the monuments, as well as the mode of affixation of names for them by the local inhabitants. I also wish to focus on certain crucial errors, as well as the insufficiency of earlier studies on the subject. To begin with, the books written in foreign languages often have mistakes in the vocabulary involved in the etymology of Khmer temples. Some researchers are not very familiar with the Khmer language, and besides, they might not have visited the site very often, or possibly also they did not pay too much attention to the oral tradition related to these ruins, a tradition that might be known to the village elders. -

Nine Deities Panel in Ancient Cambodia ផ្ទាំំ ង ចម្លាាក់់ទេ ព ប្រាំ

https://pratujournal.org ISSN 2634-176X Nine Deities Panel in Ancient Cambodia ផ្ទាំំ�ង ចម្លាាϋ់ 䟁�ពប្រាំ�厽ួន� អ ងគក្�ងុ 讶រ្យយធ揌៌ ខ្មែ�ែរ្យ 厽�殶ណ CHHUM Menghong Ministry of Culture and Fine Arts (Cambodia) [email protected] Translation by: CHHUM Menghong Edited by: Ben WREYFORD, Pratu Editorial Team Received 5 November 2018; Accepted 19 August 2019; Published 8 April 2020 The author declares no known conflict of interest. Abstract: The nine deities panel has been found in large numbers and existed with several configurations of deities in ancient Cambodia. The oldest known example dates from the pre-Angkorian period and shows the navagrahas (nine celestial bodies) in a standing posture. The iconographic form differs on Angkorian-period panels, with the nine deities on their individual vāhana (mount). By reanalysing the iconography of the deities and the typological development of the panels, it is argued that this later group represents the navadevas, a term used to designate the combination of four grahas and fivedikpālas (guardians of the directions). This study also considers issues relating to the imagery’s meaning and significance, based on their iconographic and architectural contexts in Khmer temples. The colocation of the navadevas and related iconographic themes including Viṣṇu Anantaśayana, the grahas as seven ṛṣis, and the mātṛkās, clarifies that the imagery’s meaning relates to the celestial bodies, the directions and the notion of cosmological order. The panel was used both as a lintel above a temple doorway and installed inside the sanctum as an independent object near the image of the main deity, and appears to have been especially associated with shrines located in the southeast of a temple complex. -

Palace Tours − Luxury Tours Collection the Elephant Ride Experience the Elephant Ride Experience Enjoy This Truly One of A

Palace Tours − Luxury Tours Collection The Elephant Ride Experience The Elephant Ride Experience Enjoy this truly one of a kind Cambodian experience as you choose to ride your elephant from any of the interesting locations, lending a unique flavor to your tour in Siem Reap. Marvel at the remarkable views of Bayon Temple, or pass the Terrace of the Elephants and the Leper King to witness the beauty of the quiet temple of Preah Pithu. In the afternoon let your elephant take you to view the spectacular sunsets over the forest of Phnom Bakheng, the towers of Angkor Wat and the Western Baray. ITINERARY • Day 1 − Elephant rides to Bayon Temple and Phnom Bakheng In the Morning: AA/− South Gate to Bayon Temple: Starting out around 8:00 a.m., this elephant ride takes you through the famous South Gate of Bayon along the tree lined road to the fantastic Bayon Temple. BB/− Around Bayon: Available from around 9:00 a.m. or as soon as the elephants arrive at Bayon from the South Gate. See the many faces of Bayon from a different perspective as the elephant takes you around this stunning Temple. CC/− Bayon to Preah Pithu: Available as soon as there are elephants at Bayon. This ride takes you past the Terrace of the Elephants and the Leper King to the little−known, quiet temple of Preah Pithu. DD/− Bayon to South Gate: Available from around 10:00 a.m. to 11:00 a.m. Arrive at the temples later to avoid the crowds and take an elephant from the Bayon Temple back to the South Gate. -

East of Angkor Description Some 13 Kilometers East of Siem Reap, on the Road to Phnom Penh, Is the Roluos Group of Temples

east of angkor description some 13 kilometers east of siem reap, on the road to phnom penh, is the roluos group of temples. this is the destination for the afternoon’s outing and transport from amansara by jeep can be arranged for about 3.00pm. the group comprises of three main temples, lolei, which is surrounded by an active wat, preah ko and bakong. jayavarman II chose hariharalaya (present day roluos) as one of the first capital cities of the angkor period in the 9th century. it is a great starting point for early angkorian exploration. the setting is somewhat quieter than the more popular and frequented temples within the park and is ideal for contemplative time. returning to amansara by a country road which provides the opportunity to see traditional rural life is a highlight in itself. in addition, on the road home there is one more small temple complex for the true enthusiasts, prei monti with a most unusual stone bathing pool. recent excavations suggest this may have been the site of the hariharalaya royal palace. you will arrive home at approximately 6.00pm. guests arriving into siem reap on a morning flight may wish to get started on their outings a little earlier. recommended departure for east of angkor is just after lunch with the addition of the remote temple ruin of trapeang toteung thngai. although very little of the temple remains the setting at the edge of the great lake is extremely picturesque. this hindu temple, set in a bamboo forest, was possibly founded under the reign of jayavarman III and built during the 9th century. -

Camboya Más Vendida

“ Aquí se puede ascender al reino de los dioses Para conocer la en Angkor Wat y bajar esencia del lugar a los infi ernos en la prisión de Tuol Sleng. Experienciass El presente de Camboya Camboya asombrosas Con fotografías es la embriagadora sugerentes, los lugareses imprescindibles y todaa mezcla de una historia la información de esperanzadora y primera mano. Camboya depresiva a la vez.” Organizar NICK RAY, el viaje AUTOR DE LONELY PLANET perfecto Herramientas para planifi car la visita e itinerarios para preparar el viaje ideal. Más allá de las rutas trilladas Nuestros autores desvelan los secretos locales que harán del viaje algo único. Cobertura especial Mapas de los templos de Angkor Actividades al aire libre Comida y bebida Viaje responsable Nuestro compromiso Los autores de Lonely Planet visitan los lugares sobre Los mejores los que escriben en cada edición y nunca aceptan Escanear consejos regalos a cambio de reseñas favorables: lo explican este código Nº todo tal como lo ven. para más LA GUÍA 1DE información. Los lugares OTROS TÍTULOS DE LA COLECCIÓN emblemáticos CAMBOYA CONSÚLTESE EL INTERIOR O ir a la web de Lonely MÁS VENDIDA en detalle VÉASE INTERIOR Planet en busca de CUBIERTA consejos, información Recomendaciones 10137197 y reservas de viajes. de expertos PVP. 25,00PVP. € Camboya EDICIÓN ESCRITA Y DOCUMENTADA POR Nick Ray, Jessica Lee 00-sumario.indd 1 21/10/16 12:01 PUESTA A PUNTO EXPLORAR Bienvenidos PHNOM PENH ......44 Kompong Khleang ......136 a Camboya ............. 4 Puntos de interés ........ 48 Me Chrey ..............136 Mapa de Camboya .......6 Actividades ............. 58 Las 10 mejores Cursos ................ -

Treasure of Cambodia Tour – 5 Days/ 4 Nights

Discovery Indochina Your Way! Treasure of Cambodia Tour – 5 Days/ 4 Nights Duration: 5 Days/ 4 Nights Depart From: Siem Reap Destinations: Siem Reap – Angkor Temple Complex – Phnom Penh Description: Brief Itinerary Tour Dates Destinations Meals Included Transportation Day 1 Arrival Siem Reap D By Car Pick Up Day 2 Angkor Temple Complex B, L By Car Day 3 Siem Reap – Phnom Penh B, By Car + Flight Day 4 Phnom Penh City Tour B, L By Car Day 5 Phnom Penh Departure B By Car Detailed Itinerary Day 1 Arrival in Siem Reap (D) Upon arrival we will be greet by our guide and transfer to the hotel. After that we are heading out for the majestic temples of Angkor. We will visit to the Roulous Group of temples including Preah Ko, Ba Kong and Lo Lei. This afternoon we will visit to the magnificent 12th century Angkor Wat which is believed to be the biggest religious monument ever built in the world and certainly one of the most spectacular. In the end of the day, we will enjoy sunset at the hilltop temple of Phnom Bakheng. Tonight we enjoy our welcome dinner at a fine local restaurant in town. Overnight in Siem Reap Green Discovery Indochina Head Office Address: 17A/28 Nguyen Hong, Dong Da Dist, Hanoi,Vietnam Tel : +84 439381242 Fax: +84 439381242 Mobile:+84987184390 E-mail : [email protected] Website: www.greendiscoveryindochina.com Discovery Indochina Your Way! Day 2 Angkor Temple Complex (B/L) Today, we visit of the amazing temples complex of Angkor. The beginning is to explore the complex of Angkor Thom. -

프레아피투 까오썩 사원(사원T) 치수계획 연구 7 ISSN 1598-1142 (Print) / ISSN 2383-9066 (Online)

프레아피투 까오썩 사원(사원T) 치수계획 연구 7 ISSN 1598-1142 (Print) / ISSN 2383-9066 (Online) https://doi.org/10.7738/JAH.2018.27.5.007 프레아피투 까오썩 사원(사원T) 치수계획 연구 - 앙코르유적 “프레아피투 사원” 연구(2) - A Study on the Dimensional plan of Kor Sork Temple(temple T) on the Preah Pithu Monument Group - A study of Preah Pithu Monument in Angkor(2) - 박 동 희*1) Park, Dong-hee (한국문화재재단 연구원, 건축학박사) Abstract This study investigated the dimensional plan of Kor Sork temple in Preah Pithu complex, Angkor by civil surveying, 3D scan, measured integer ratio and regularity. According to epitaph and preceding researches, Khmer temples were built based on structural planing with the constant ratio and regularity by using special construct measure scales "Hasta" and “Byama”. The study assumed the same unit method was applied in Kor Sork temple and identified the regularity of actual measurement value about the temple. The assumed construct measure scale (Hasta) used for the design of this temple is 413mm. The overall apart arrangement of the temple is different in the East-West direction and the North-South direction. In the East-West direction, the whole scale is 180 hasta, and it is divided into 20 hastas. On the other hands, it was confirmed that the North-South direction is 96 hasta and it was divided four quadrants in 24 hastas. Regarding the detailed design, the regularity according to the constant ratio was confirmed. 7 hasta was used as the basic unit on the first floor and 6 hasta were used as the basic unit on the second floor of the terrace.