Nine Deities Panel in Ancient Cambodia ផ្ទាំំ ង ចម្លាាក់់ទេ ព ប្រាំ

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Inventaire-CIK-09042017.Pdf

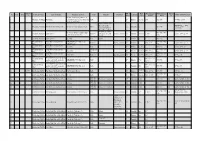

Autre(s) Nb de Date Estampages Estampages Autres K. Ext. Ind. Pays, province Lieu d’origine Situation actuelle Type Détails Matériau Langue Éditions/traductions n° lignes (śaka) EFEO BNF est. In situ ; dans la maçonnerie de 1 - - - Vietnam, An Giang Vat Thling l’autel de la pagode du village de Stèle 26 Khmer vie-viie 271 302 (34) - IC VI, p. 28-30 Lê Hoat, Châu Đốc Dalle formant seuil du tombeau du BEFEO XL, p. 480 2 - - - Vietnam, An Giang Phnom Svam ou Nui Sam In situ (en 1923, Cœdès 1923) Dalle 12 Sanskrit xe - 301 (34) - mandarin Nguyên (chronique) Ngoc Thoai ; Ruinée Trouvée sur l'allée In situ (en 2002), enchassé dans 303 (34) ; 471 3 - - - Vietnam, An Giang Linh Son Tu Piédroit principale de Linh Schiste ardoisier 11 Sanskrit vie-viie n. 295 - Cœdès 1936, p. 7-9 l'autel de Linh Son Tu (79) Son Tu 4 - - - Vietnam, An Giang Linh Son Tu Inconnue Stèle Ruinée 12 Khmer xe - 304 (34) - - Vietnam, Đồng Thap Muoi, Prasat Pram BTLSHCM 2893 (Kp 1, 2) ; 305 (69) ; 472 5 - - - Piédroit Schiste ardoisier 22 Sanskrit ve 329 ; n. 15 - Cœdès 1931, p. 1-7 Tháp Loveng BTLS 5964? (79) Vietnam, Đồng Thap Muoi, Prasat Pram 6 - - - Inconnue Stèle 10 Khmer vie-viie - 306 (34) - Cœdès 1936, p. 5 Tháp Loveng Vietnam, Đồng Thap Muoi, Prasat Pram Chapiteau 307 (34) ; 473 7 - - - Inconnue 20 Khmer vie-viie 331 ; n. 16 - Cœdès 1936, p. 3-5 Tháp Loveng (?) (79) Vietnam, Đồng Thap Muoi, Prasat Pram 308 (34) ; 474 8 - - - DCA 6811 Piédroit Schiste ardoisier 10 Khmer vie-viie 259 ; n. -

Tapas in the Rg Veda

TAPAS IN THE ---RG VEDA TAPAS IN THE RG VEDA By ANTHONY L. MURUOCK, B.A. A Thesis Submitted to the School of Graduate Studies in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts McMaster University April 1983 MASTER OF ARTS (1983) McMaster University (Religious Studies) Hamilton, Ontario TITLE: Tapas in the fuL Veda AUTHOR: Anthony L. Murdock, B.A. (York University) SUPERVISORS: Professor D. Kinsley Professor P. Younger Professor P. Granoff NUMBER OF PAGES: v, 95 ii ABSTRACT It is my contention in this thesis that the term tapas means heat, and heat only, in the Bi[ Veda. Many reputable scholars have suggested that tapas refers to asceticism in several instances in the RV. I propose that these suggestions are in fact unnecessary. To determine the exact meaning of tapas in its many occurrences in the RV, I have given primary attention to those contexts (i.e. hymns) in which the meaning of tapas is absolutely unambiguous. I then proceed with this meaning in mind to more ambiguous instances. In those instances where the meaning of tapas is unambiguous it always refers to some kind of heat, and never to asceticism. Since there are unambiguous cases where ~apas means heat in the RV, and there are no unambiguous instances in the RV where tapas means asceticism, it only seems natural to assume that tapas means heat in all instances. The various occurrences of tapas as heat are organized in a new system of contextual classifications to demonstrate that tapas as heat still has a variety of functions and usages in the RV. -

A Study of the Early Vedic Age in Ancient India

Journal of Arts and Culture ISSN: 0976-9862 & E-ISSN: 0976-9870, Volume 3, Issue 3, 2012, pp.-129-132. Available online at http://www.bioinfo.in/contents.php?id=53. A STUDY OF THE EARLY VEDIC AGE IN ANCIENT INDIA FASALE M.K.* Department of Histroy, Abasaheb Kakade Arts College, Bodhegaon, Shevgaon- 414 502, MS, India *Corresponding Author: Email- [email protected] Received: December 04, 2012; Accepted: December 20, 2012 Abstract- The Vedic period (or Vedic age) was a period in history during which the Vedas, the oldest scriptures of Hinduism, were composed. The time span of the period is uncertain. Philological and linguistic evidence indicates that the Rigveda, the oldest of the Vedas, was com- posed roughly between 1700 and 1100 BCE, also referred to as the early Vedic period. The end of the period is commonly estimated to have occurred about 500 BCE, and 150 BCE has been suggested as a terminus ante quem for all Vedic Sanskrit literature. Transmission of texts in the Vedic period was by oral tradition alone, and a literary tradition set in only in post-Vedic times. Despite the difficulties in dating the period, the Vedas can safely be assumed to be several thousands of years old. The associated culture, sometimes referred to as Vedic civilization, was probably centred early on in the northern and northwestern parts of the Indian subcontinent, but has now spread and constitutes the basis of contemporary Indian culture. After the end of the Vedic period, the Mahajanapadas period in turn gave way to the Maurya Empire (from ca. -

A Review on - Amlapitta in Kashyapa Samhita

Original Research Article DOI: 10.18231/2394-2797.2017.0002 A Review on - Amlapitta in Kashyapa Samhita Nilambari L. Darade1, Yawatkar PC2 1PG Student, Dept. of Samhita, 2HOD, Dept. of Samhita & Siddhantha SVNTH’s Ayurved College, Rahuri Factory, Ahmadnagar, Maharashtra *Corresponding Author: Email: [email protected] Abstract Amlapitta is most common disorders in the society nowadays, due to indulgence in incompatible food habits and activities. In Brihatrayees of Ayurveda, scattered references are only available about Amlapitta. Kashyapa Samhita was the first Samhita which gives a detailed explanation of the disease along with its etiology, signs and symptoms with its treatment protocols. A group of drugs and Pathyas in Amlapitta are explained and shifting of the place is also advised when all the other treatment modalities fail to manage the condition. The present review intended to explore the important aspect of Amlapitta and its management as described in Kashyapa Samhita, which can be helpful to understand the etiopathogenesis of disease with more clarity and ultimately in its management, which is still a challenging task for Ayurveda physician. Keywords: Amlapitta, Dosha, Aushadhi, Drava, Kashyapa Samhita, Agni Introduction Acharya Charaka has not mentioned Amlapitta as a Amlapitta is a disease of Annahava Srotas and is separate disease, but he has given many scattered more common in the present scenario of unhealthy diets references regarding Amlapitta, which are as follow. & regimens. The term Amlapitta is a compound one While explaining the indications of Ashtavidha Ksheera comprising of the words Amla and Pitta out of these, & Kamsa Haritaki, Amlapitta has also been listed and the word Amla is indicative of a property which is Kulattha (Dolichos biflorus Linn.) has been considered organoleptic in nature and identified through the tongue as chief etiological factor of Amlapitta in Agrya while the word Pitta is suggestive of one of the Tridosas Prakarana. -

The Significance of Fire Offering in Hindu Society

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF MULTIDISCIPLINARY EDUCATIONAL RESEARCH ISSN : 2277-7881; IMPACT FACTOR - 2.735; IC VALUE:5.16 VOLUME 3, ISSUE 7(3), JULY 2014 THE SIGNIFICANCE OF FIRE OFFERING IN HINDU THE SIGNIFICANCESOCIETY OF FIRE OFFERING IN HINDU SOCIETY S. Sushrutha H. R. Nagendra Swami Vivekananda Yoga Swami Vivekananda Yoga University University Bangalore, India Bangalore, India R. G. Bhat Swami Vivekananda Yoga University Bangalore, India Introduction Vedas demonstrate three domains of living for betterment of process and they include karma (action), dhyana (meditation) and jnana (knowledge). As long as individuality continues as human being, actions will follow and it will eventually lead to knowledge. According to the Dhatupatha the word yajna derives from yaj* in Sanskrit language that broadly means, [a] worship of GODs (natural forces), [b] synchronisation between various domains of creation and [c] charity.1 The concept of God differs from religion to religion. The ancient Hindu scriptures conceptualises Natural forces as GOD or Devatas (deva that which enlightens [div = light]). Commonly in all ancient civilizations the worship of Natural forces as GODs was prevalent. Therefore any form of manifested (Sun, fire and so on) and or unmanifested (Prana, Manas and so on) form of energy is considered as GOD even in Hindu tradition. Worship conceives the idea of requite to the sources of energy forms from where the energy is drawn for the use of all 260 INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF MULTIDISCIPLINARY EDUCATIONAL RESEARCH ISSN : 2277-7881; IMPACT FACTOR - 2.735; IC VALUE:5.16 VOLUME 3, ISSUE 7(3), JULY 2014 life forms. Worshiping the Gods (Upasana) can be in the form of worship of manifest forms, prostration, collection of ingredients or devotees for worship, invocation, study and discourse and meditation. -

Cambodia-10-Contents.Pdf

©Lonely Planet Publications Pty Ltd Cambodia Temples of Angkor p129 ^# ^# Siem Reap p93 Northwestern Eastern Cambodia Cambodia p270 p228 #_ Phnom Penh p36 South Coast p172 THIS EDITION WRITTEN AND RESEARCHED BY Nick Ray, Jessica Lee PLAN YOUR TRIP ON THE ROAD Welcome to Cambodia . 4 PHNOM PENH . 36 TEMPLES OF Cambodia Map . 6 Sights . 40 ANGKOR . 129 Cambodia’s Top 10 . 8 Activities . 50 Angkor Wat . 144 Need to Know . 14 Courses . 55 Angkor Thom . 148 Bayon 149 If You Like… . 16 Tours . 55 .. Sleeping . 56 Baphuon 154 Month by Month . 18 . Eating . 62 Royal Enclosure & Itineraries . 20 Drinking & Nightlife . 73 Phimeanakas . 154 Off the Beaten Track . 26 Entertainment . 76 Preah Palilay . 154 Outdoor Adventures . 28 Shopping . 78 Tep Pranam . 155 Preah Pithu 155 Regions at a Glance . 33 Around Phnom Penh . 88 . Koh Dach 88 Terrace of the . Leper King 155 Udong 88 . Terrace of Elephants 155 Tonlé Bati 90 . .. Kleangs & Prasat Phnom Tamao Wildlife Suor Prat 155 Rescue Centre . 90 . Around Angkor Thom . 156 Phnom Chisor 91 . Baksei Chamkrong 156 . CHRISTOPHER GROENHOUT / GETTY IMAGES © IMAGES GETTY / GROENHOUT CHRISTOPHER Kirirom National Park . 91 Phnom Bakheng. 156 SIEM REAP . 93 Chau Say Tevoda . 157 Thommanon 157 Sights . 95 . Spean Thmor 157 Activities . 99 .. Ta Keo 158 Courses . 101 . Ta Nei 158 Tours . 102 . Ta Prohm 158 Sleeping . 103 . Banteay Kdei Eating . 107 & Sra Srang . 159 Drinking & Nightlife . 115 Prasat Kravan . 159 PSAR THMEI P79, Entertainment . 117. Preah Khan 160 PHNOM PENH . Shopping . 118 Preah Neak Poan . 161 Around Siem Reap . 124 Ta Som 162 . TIM HUGHES / GETTY IMAGES © IMAGES GETTY / HUGHES TIM Banteay Srei District . -

Ayurveda Tips to Balance Agni

Yoga. Ayurveda.Joyful Living www.katetowell.com Ayurveda Tips to Balance Agni Healthy Agni is essential for our wellbeing; in fact, according to Ayurveda impaired Agni is the root of most imbalance & disease we experience. Agni is often thought of as your digestive fire but it is so much more. It is our ability to digest food, information & emotion & the intelligence that drives us physically, mentally & spiritually. Nurturing Agni helps to improve digestion, boost energy levels & enhance your overall state of well-being. The first step in creating lasting health is to establish balanced Agni. Here are 8 Ayurveda Tips to balance & optimize your Agni. Feed Your Fire Well Cold drinks, especially How, what & when you eat are all ice water, dampen Agni. important factors in keeping up your It is best to avoid iced digestive fire. Eat whole foods according 2 drinks, especially with to the season & your dosha. Avoid meals. Sip warm water 1 between meals. overeating, eating when upset, eating late at night, eating while driving & snacking. No Ice, Ice Baby There are number of spices Make Lunch Your # 1 that support Agni including; This is a tough one for most people but ginger, cumin, cardamom & super important. Your digestive fire is fennel. Cook with Ghee it is 4 most active mid-day & making lunch 3 fantastic for building Agni! your biggest meal promotes optimal digestion and supports weight loss. Use Spices & Ghee Have a Routine Cleanse Seasonally Setting your rhythm to the rhythm Seasonal cleanses are a powerful way of nature is key in establishing to kindle & reset Agni. -

Claiming the Hydraulic Network of Angkor with Viṣṇu

Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports 9 (2016) 275–292 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Journal of Archaeological Science: Reports journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/jasrep Claiming the hydraulic network of Angkor with Viṣṇu: A multidisciplinary approach including the analysis of archaeological remains, digital modelling and radiocarbon dating: With evidence for a 12th century renovation of the West Mebon Marnie Feneley a,⁎, Dan Penny b, Roland Fletcher b a University of Sydney and currently at University of NSW, Australia b University of Sydney, Australia article info abstract Article history: Prior to the investigations in 2004–2005 of the West Mebon and subsequent analysis of archaeological material in Received 23 April 2016 2015 it was presumed that the Mebon was built in the mid-11th century and consecrated only once. New data Received in revised form 8 June 2016 indicates a possible re-use of the water shrine and a refurbishment and reconsecration in the early 12th century, Accepted 14 June 2016 at which time a large sculpture of Viṣṇu was installed. Understanding the context of the West Mebon is vital to Available online 11 August 2016 understanding the complex hydraulic network of Angkor, which plays a crucial role in the history of the Empire. Keywords: © 2016 The Authors. Published by Elsevier Ltd. This is an open access article under the CC BY-NC-ND license Archaeology (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/). Angkor Digital visualisation 3D max Hydraulic network Bronze sculpture Viṣṇu West Mebon 14C dates Angkor Wat Contents 1. Introduction.............................................................. 276 2. The West Mebon — background.................................................... -

Virtual Sambor Prei Kuk: an Interactive Learning Tool

Virtual Sambor Prei Kuk: An Interactive Learning Tool Daniel MICHON Religious Studies, Claremont McKenna College Claremont, CA 91711 and Yehuda KALAY Faculty of Architecture and Town Planning The Technion - Israel Institute of Technology Haifa 32000, Israel ABSTRACT along the trade routes from its Indic origins into Southeast Asia—one of the great cultural assimilations in human history. MUVEs (Multi-User Virtual Environments) are a new media for researching the genesis and evolution of sites of cultural Much of this important work has, so far, remained the exclusive significance. MUVEs are able to model both the tangible and province of researchers, hidden from the general public who intangible heritage of a site, allowing the user to obtain a more might find it justifiably interesting. Further, the advent of dynamic understanding of the culture. This paper illustrates a immersive, interactive, Web-enabled, Multi-User Virtual cultural heritage project which captures and communicates the Environments (MUVEs) has provided us with the opportunity interplay of context (geography), content (architecture and to tell the story of Sambor Prei Kuk in a way that can help artifacts) and temporal activity (rituals and everyday life) visitors experience this remarkable cultural heritage as it might leading to a unique digital archive of the tangible and intangible have been in the seventh-eighth century CE. MUVEs are a new heritage of the temple complex at Sambor Prei Kuk, Cambodia, media vehicle that has the ability to communicate cultural circa seventh-eighth century CE. The MUVE is used to provide heritage experience in a way that is a cross between a platform which enables the experience of weaved tangible and filmmaking, video games, and architectural design. -

Hanuman Chalisa.Pdf

Shree Hanuman Chaleesa a sacred thread adorns your shoulder. Gate of Sweet Nectar 6. Shankara suwana Kesaree nandana, Teja prataapa mahaa jaga bandana Shree Guru charana saroja raja nija You are an incarnation of Shiva and manu mukuru sudhari Kesari's son/ Taking the dust of my Guru's lotus feet to Your glory is revered throughout the world. polish the mirror of my heart 7. Bidyaawaana gunee ati chaatura, Baranaun Raghubara bimala jasu jo Raama kaaja karibe ko aatura daayaku phala chaari You are the wisest of the wise, virtuous and I sing the pure fame of the best of Raghus, very clever/ which bestows the four fruits of life. ever eager to do Ram's work Buddhi heena tanu jaanike sumiraun 8. Prabhu charitra sunibe ko rasiyaa, pawana kumaara Raama Lakhana Seetaa mana basiyaa I don’t know anything, so I remember you, You delight in hearing of the Lord's deeds/ Son of the Wind Ram, Lakshman and Sita dwell in your heart. Bala budhi vidyaa dehu mohin harahu kalesa bikaara 9. Sookshma roopa dhari Siyahin Grant me strength, intelligence and dikhaawaa, wisdom and remove my impurities and Bikata roopa dhari Lankaa jaraawaa sorrows Assuming a tiny form you appeared to Sita/ in an awesome form you burned Lanka. 1. Jaya Hanumaan gyaana guna saagara, Jaya Kapeesha tihun loka ujaagara 10. Bheema roopa dhari asura sanghaare, Hail Hanuman, ocean of wisdom/ Raamachandra ke kaaja sanvaare Hail Monkey Lord! You light up the three Taking a dreadful form you slaughtered worlds. the demons/ completing Lord Ram's work. -

Bhagavad Gita Chapter 10: Divine Emanations

Bhagavad Gita Chapter 10: Divine Emanations Tonight we will be doing chapter 10 of the Bhagavad Gita, Vibhuti Yoga, The Yoga of Divine Emanations. But first I want to talk about the nature of the journey. For most of us Westerners this aspect of the Gita is not available to us. Very few people in the West open up to God, to the collective consciousness, in the experiential way that is being revealed here. Most spiritual teachings have more to do with the development of the psychic intelligence and its relationship to truth. Vibhuti Yoga is truly devotional. A vast majority of people have a devotional relationship or feeling for whatever God or Allah or Zoroaster represents. It comes from something in our human nature that is transferring onto an idea, from the human collective consciousness, and is different from what we will be talking about today. (2:00) Vibhuti Yoga is a direct revelation from the universe to the individual. What we might call devotion is absolutely felt, but of a completely different order than what we would call religious devotion or the fervor that occurs with born again Christians or with people that are motivated from their vital for this passionate relationship, for this idea of God. That comes from the higher heart, the higher vital, the part of our human nature that is rising up from our focus on our relationships and attachments and identifications associated with community and society. It is a part of us that lifts to a possibility. It is to some extent associated with what I call the psychic heart. -

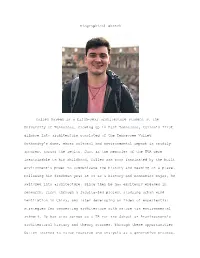

Biographical Sketch Cullen Sayegh Is a Fifth-Year Architecture Student At

Biographical Sketch Cullen Sayegh is a fifth-year architecture student at the University of Tennessee. Growing up in East Tennessee, Cullen’s first glimpse into architecture consisted of the Tennessee Valley Authority’s dams, whose cultural and environmental impact is readily apparent across the region. Just as the memories of the TVA were inextricable to his childhood, Cullen was soon fascinated by the built environment’s power to communicate the history and meaning of a place. Following his freshman year at UT as a history and economics major, he switched into architecture. Since then he has excitedly engaged in research, first through a faculty-led project studying urban wind ventilation in China, and later developing an index of experiential strategies for connecting architecture with nature via environmental stimuli. He has also served as a TA for the School of Architecture’s architectural history and theory courses. Through these opportunities Cullen learned to value research and analysis as a generative process. These experiences all proved formative in developing Cullen’s proposal for the Aydelott Award. From initially brainstorming sites, to the grant-writing process, to finally beginning the trip and visiting each site, the Aydelott Travel Award has proven to be a career-altering experience. This opportunity has provided him with the confidence and enthusiasm to apply for a 2019 Fulbright Grant, pending at the time of this report. Cullen hopes to eventually take the knowledge he developed over the course of his Aydelott experience and leverage it in the future as he pursues a graduate degree in architectural history. Student: Cullen Sayegh Faculty Mentor: Dr.