Vedic Brahmanism and Its Offshoots

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Emergence of the Mahajanapadas

The Emergence of the Mahajanapadas Sanjay Sharma Introduction In the post-Vedic period, the centre of activity shifted from the upper Ganga valley or madhyadesha to middle and lower Ganga valleys known in the contemporary Buddhist texts as majjhimadesha. Painted grey ware pottery gave way to a richer and shinier northern black polished ware which signified new trends in commercial activities and rising levels of prosperity. Imprtant features of the period between c. 600 and 321 BC include, inter-alia, rise of ‘heterodox belief systems’ resulting in an intellectual revolution, expansion of trade and commerce leading to the emergence of urban life mainly in the region of Ganga valley and evolution of vast territorial states called the mahajanapadas from the smaller ones of the later Vedic period which, as we have seen, were known as the janapadas. Increased surplus production resulted in the expansion of trading activities on one hand and an increase in the amount of taxes for the ruler on the other. The latter helped in the evolution of large territorial states and increased commercial activity facilitated the growth of cities and towns along with the evolution of money economy. The ruling and the priestly elites cornered most of the agricultural surplus produced by the vaishyas and the shudras (as labourers). The varna system became more consolidated and perpetual. It was in this background that the two great belief systems, Jainism and Buddhism, emerged. They posed serious challenge to the Brahmanical socio-religious philosophy. These belief systems had a primary aim to liberate the lower classes from the fetters of orthodox Brahmanism. -

A Study of the Early Vedic Age in Ancient India

Journal of Arts and Culture ISSN: 0976-9862 & E-ISSN: 0976-9870, Volume 3, Issue 3, 2012, pp.-129-132. Available online at http://www.bioinfo.in/contents.php?id=53. A STUDY OF THE EARLY VEDIC AGE IN ANCIENT INDIA FASALE M.K.* Department of Histroy, Abasaheb Kakade Arts College, Bodhegaon, Shevgaon- 414 502, MS, India *Corresponding Author: Email- [email protected] Received: December 04, 2012; Accepted: December 20, 2012 Abstract- The Vedic period (or Vedic age) was a period in history during which the Vedas, the oldest scriptures of Hinduism, were composed. The time span of the period is uncertain. Philological and linguistic evidence indicates that the Rigveda, the oldest of the Vedas, was com- posed roughly between 1700 and 1100 BCE, also referred to as the early Vedic period. The end of the period is commonly estimated to have occurred about 500 BCE, and 150 BCE has been suggested as a terminus ante quem for all Vedic Sanskrit literature. Transmission of texts in the Vedic period was by oral tradition alone, and a literary tradition set in only in post-Vedic times. Despite the difficulties in dating the period, the Vedas can safely be assumed to be several thousands of years old. The associated culture, sometimes referred to as Vedic civilization, was probably centred early on in the northern and northwestern parts of the Indian subcontinent, but has now spread and constitutes the basis of contemporary Indian culture. After the end of the Vedic period, the Mahajanapadas period in turn gave way to the Maurya Empire (from ca. -

A Review on - Amlapitta in Kashyapa Samhita

Original Research Article DOI: 10.18231/2394-2797.2017.0002 A Review on - Amlapitta in Kashyapa Samhita Nilambari L. Darade1, Yawatkar PC2 1PG Student, Dept. of Samhita, 2HOD, Dept. of Samhita & Siddhantha SVNTH’s Ayurved College, Rahuri Factory, Ahmadnagar, Maharashtra *Corresponding Author: Email: [email protected] Abstract Amlapitta is most common disorders in the society nowadays, due to indulgence in incompatible food habits and activities. In Brihatrayees of Ayurveda, scattered references are only available about Amlapitta. Kashyapa Samhita was the first Samhita which gives a detailed explanation of the disease along with its etiology, signs and symptoms with its treatment protocols. A group of drugs and Pathyas in Amlapitta are explained and shifting of the place is also advised when all the other treatment modalities fail to manage the condition. The present review intended to explore the important aspect of Amlapitta and its management as described in Kashyapa Samhita, which can be helpful to understand the etiopathogenesis of disease with more clarity and ultimately in its management, which is still a challenging task for Ayurveda physician. Keywords: Amlapitta, Dosha, Aushadhi, Drava, Kashyapa Samhita, Agni Introduction Acharya Charaka has not mentioned Amlapitta as a Amlapitta is a disease of Annahava Srotas and is separate disease, but he has given many scattered more common in the present scenario of unhealthy diets references regarding Amlapitta, which are as follow. & regimens. The term Amlapitta is a compound one While explaining the indications of Ashtavidha Ksheera comprising of the words Amla and Pitta out of these, & Kamsa Haritaki, Amlapitta has also been listed and the word Amla is indicative of a property which is Kulattha (Dolichos biflorus Linn.) has been considered organoleptic in nature and identified through the tongue as chief etiological factor of Amlapitta in Agrya while the word Pitta is suggestive of one of the Tridosas Prakarana. -

All Chapters.Pmd

CHAPTER 5 KINGDOMS, KINGS AND AN EARLEARLEARLY REPUBLIC Election dadaElection y Shankaran woke up to see his grandparents all ready to go and vote. They wanted to be the first to reach the polling booth. Why, Shankaran wanted to know, were they so excited? Somewhat impatiently, his grandfather explained: “We can choose our own rulers today.” HoHoHow some men became rulers Choosing leaders or rulers by voting is something that has become common during the last fifty years or so. How did men become rulers in the past? Some of the rajas we read about in Chapter 4 were probably chosen by the jana, the people. But, around 3000 years ago, we find some changes taking place in the ways in which rajas were chosen.NCERT Some men now became recognised as rajas by perforrepublishedming very big sacrifices. The© ashvamedha or horse sacrifice was one such ritual. Abe horse was let loose to wander freely and it was guarded by the raja’s men. If the horse wanderedto into the kingdoms of other rajas and they stopped it, they had to fight. If they allowed thenot horse to pass, it meant that they accepted that the raja who wanted to perform the sacrifice was stronger than them. These rajas were then invited to the sacrifice, which was performed by specially trained priests, who were rewarded with gifts. The raja who organised the sacrifice was recognised as being very powerful, and all those who came brought gifts for him. The raja was a central figure in these rituals. He often had a special seat, a throne or a tiger n 46 skin. -

The Significance of Fire Offering in Hindu Society

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF MULTIDISCIPLINARY EDUCATIONAL RESEARCH ISSN : 2277-7881; IMPACT FACTOR - 2.735; IC VALUE:5.16 VOLUME 3, ISSUE 7(3), JULY 2014 THE SIGNIFICANCE OF FIRE OFFERING IN HINDU THE SIGNIFICANCESOCIETY OF FIRE OFFERING IN HINDU SOCIETY S. Sushrutha H. R. Nagendra Swami Vivekananda Yoga Swami Vivekananda Yoga University University Bangalore, India Bangalore, India R. G. Bhat Swami Vivekananda Yoga University Bangalore, India Introduction Vedas demonstrate three domains of living for betterment of process and they include karma (action), dhyana (meditation) and jnana (knowledge). As long as individuality continues as human being, actions will follow and it will eventually lead to knowledge. According to the Dhatupatha the word yajna derives from yaj* in Sanskrit language that broadly means, [a] worship of GODs (natural forces), [b] synchronisation between various domains of creation and [c] charity.1 The concept of God differs from religion to religion. The ancient Hindu scriptures conceptualises Natural forces as GOD or Devatas (deva that which enlightens [div = light]). Commonly in all ancient civilizations the worship of Natural forces as GODs was prevalent. Therefore any form of manifested (Sun, fire and so on) and or unmanifested (Prana, Manas and so on) form of energy is considered as GOD even in Hindu tradition. Worship conceives the idea of requite to the sources of energy forms from where the energy is drawn for the use of all 260 INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF MULTIDISCIPLINARY EDUCATIONAL RESEARCH ISSN : 2277-7881; IMPACT FACTOR - 2.735; IC VALUE:5.16 VOLUME 3, ISSUE 7(3), JULY 2014 life forms. Worshiping the Gods (Upasana) can be in the form of worship of manifest forms, prostration, collection of ingredients or devotees for worship, invocation, study and discourse and meditation. -

Bhakti and Sraddha

(8) Journal of Indian and Buddhist Studies Vol. 41, No. 1, December 1992 Bhakti and Sraddha Norio SEKIDO As Mahayana Buddhism developed, the concept of God, Buddha as God begin to take place. The tradition of worship gradually increased. One critic says that after the demise of Buddha, slowly and slowly his image was adorned by his followers. The major and minor disciples accepted him as the supreme God). Thus devotion or bhakti emerged in Mahayana Buddhism. He was called Amitabha Buddha.2) Vasubandhu prescribed five methods of worship like the Hindu concept of devotion. The repetition of the name of Buddha has been conceived to be essential for the realisation of freedom from suffering in many sects of Mahayana Buddhism. Fa-hien then reached Pataliputra, where he came across a distinguished Brahmana called Radhasvami, who. was a Buddhist by faith. He had clear discernment and deep knowledge. He taught Mahayana doctrines to Fa-hien. He was revered by the king of the country. He was instrumental in popularising Buddhism. Sramanas from other countries came to comprehend the Truth. By the side of the ASoka stupa, there was a Mahayana monastery, grand and beautiful, there was also a Hinayana monastery. The two together had about 600 to 700 monks. Here was another teacher known as Manjusri, who was proficient like Radhasvami. To him flocked Maha- yana students from all countries. Modern scholars of the Bhagavad-Gita have almost unf ormly translated the word Sraddha with the English word faith' or the German word Glaube. In view of the near unanimity of preference for the word faith in translating the word Sraddha, one is apt to think that the word adequately conveys the significance of the original.3 As in Bhakti in Hinduism, the company of sutra is very helpful for the -533- Bhakti and Sraddha (N. -

Linguistics Development Team

Development Team Principal Investigator: Prof. Pramod Pandey Centre for Linguistics / SLL&CS Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi Email: [email protected] Paper Coordinator: Prof. K. S. Nagaraja Department of Linguistics, Deccan College Post-Graduate Research Institute, Pune- 411006, [email protected] Content Writer: Prof. K. S. Nagaraja Prof H. S. Ananthanarayana Content Reviewer: Retd Prof, Department of Linguistics Osmania University, Hyderabad 500007 Paper : Historical and Comparative Linguistics Linguistics Module : Indo-Aryan Language Family Description of Module Subject Name Linguistics Paper Name Historical and Comparative Linguistics Module Title Indo-Aryan Language Family Module ID Lings_P7_M1 Quadrant 1 E-Text Paper : Historical and Comparative Linguistics Linguistics Module : Indo-Aryan Language Family INDO-ARYAN LANGUAGE FAMILY The Indo-Aryan migration theory proposes that the Indo-Aryans migrated from the Central Asian steppes into South Asia during the early part of the 2nd millennium BCE, bringing with them the Indo-Aryan languages. Migration by an Indo-European people was first hypothesized in the late 18th century, following the discovery of the Indo-European language family, when similarities between Western and Indian languages had been noted. Given these similarities, a single source or origin was proposed, which was diffused by migrations from some original homeland. This linguistic argument is supported by archaeological and anthropological research. Genetic research reveals that those migrations form part of a complex genetical puzzle on the origin and spread of the various components of the Indian population. Literary research reveals similarities between various, geographically distinct, Indo-Aryan historical cultures. The Indo-Aryan migrations started in approximately 1800 BCE, after the invention of the war chariot, and also brought Indo-Aryan languages into the Levant and possibly Inner Asia. -

Part 4 Hare Krishna Prabhujis and Matajis, Please Accept My

Give Your Best to Krishna - Part 4 Date: 2020-09-04 Author: Sudarshana devi dasi Hare Krishna Prabhujis and Matajis, Please accept my humble obeisances. All glories to Srila Prabhupada and Srila Gurudeva. This is in continuation of the previous offering titled, "Give Your Best to Krishna" wherein we were meditating on Srimad Bhagavatam verse 1.14.38. In the previous offerings we saw 1) The members of Yadu family, pure devotees, always give best possible thing to Krishna. 2) Best part of day (early morning hours), our life (childhood and healthy body) should be dedicated to Krishna. 3) Best service is to give Krishna to all - in the form of Holy Names, Bhagavad Gita and Bhagavatam. 4) Hand-over everything to Krishna and be fearless. Now we shall try to meditate on this verse further. In Srimad Bhagavatam Canto 8, we find the nice example of Bali Maharaj who surrendered himself completely to Lord Vamanadev. Lord Vamana appeared in the sacrificial arena of Bali Maharaj in the form a dwarf brahmana. Bali Maharaj received Him nicely, washed His lotus feet and sprinkled the water on his head and requested Him to ask for charity. Lord asked him for 3 paces of land. Sukracarya knew that dwarf brahmana Vamana is Lord Vishnu and so he forbade his disciple not to give charity. He explained that in subduing others, in joking, in responding to danger, in acting for the welfare of others, and so on, one could refuse to fulfill one’s promise, and there would be no fault. By this philosophy, Śukracarya tried to dissuade Bali Mahāraja from giving land to Lord Vamanadeva. -

Unit 39 Developments in Religion

UNIT 39 DEVELOPMENTS IN RELIGION Structure Objectives Introduction Emergence of Bhakti in Brahmanism 39.2.1 Syncretism of Deities 39.2.2 Adaptation of Tribal Rituals 39.2.3 Royal Support to Temples and Theism. Spread of Bh&ti to South India Bhakti Movement in South India Protest and Reform in the Bhakti Movement of the South and later Transformation of the Bhakti Movement Emergence of Tantrism 39.6.1 some Main Features of Tantrism 39.6.2 Tantrism and the Heterodox Religions Let Us Sum Up Key Words Answers to Check Your Progress Exercises OBJECTIVES The purpose of this Unit is to briefly discuss the major features of Eligious developments in the early medieval period with focus on the shape which Bhakti ideology and Tantrism took. After going through this Unit you should be able to : know about the origins of Bhakti in Brahmanical religious order, know the character and social context of the characteristic of later Brahmanism, know how the character and social context of Bhakti changed in the e&ly medieval period, realise how royal support to.Bhakti cults gave them wealthy institutional bases, know about the origin and role of Tantrism and its character in the early medieval period, and know hbw Tantrism penetrated into Buddhism and Jainism. INTRODUCTION You are by now familiar with certain broad stages of the religious history of early India. While archaeological material suggests that certain elements of Indian religions were present in the archaeological cultures dating prior to the Vedas, the hymns of the Rig Veda give us for the first time, an idea of how prayers were offered tc deities to please them. -

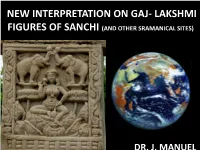

Female Deity of Sanchi on Lotus As Early Images of Bhu Devi J

NEW INTERPRETATION ON GAJ- LAKSHMI FIGURES OF SANCHI (AND OTHER SRAMANICAL SITES) nn DR. J. MANUEL THE BACK GROUND • INDRA RULED THE ROOST IN THE RGVEDIC AGE • OTHER GODS LIKE AGNI, SOMA, VARUN, SURYA BESIDES ASHVINIKUMARS, MARUTS WERE ALSO SPOKEN VERY HIGH IN THE LITERATURE • VISHNU IS ALSO KNOWN WITH INCREASING PROMINENCE SO MUCH SO IN THE LATE MANDALA 1 SUKT 22 A STRETCH OF SIX VERSES MENTION HIS POWER AND EFFECT • EVIDENTLY HIS GLORY WAS BEING FELT MORE AND MORE AS TIME PASSED • Mandal I Sukt 22 Richa 19 • Vishnu ki kripa say …….. Vishnu kay karyon ko dekho. Vay Indra kay upyukt sakha hai EVIDENTLY HIS GLORY WAS BEING FELT MORE AND MORE AS TIME PASSED AND HERO-GODS LIKE BALARAM AND VASUDEVA WERE ACCEPTED AS HIS INCARNATIONS • CHILAS IN PAKISTAN • AGATHOCLEUS COINS • TIKLA NEAR GWALIOR • ARE SOME EVIDENCE OF HERO-GODS BUT NOT VEDIC VISHNU IN SECOND CENTURY BC • There is the Kheri-Gujjar Figure also of the Therio anthropomorphic copper image BUT • FOR A LONG TIME INDRA CONTINUED TO HOLD THE FORT OF DOMINANCE • THIS IS SEEN IN EARLY SACRED LITERATURE AND ART ANTHROPOMORPHIC FIGURES • OF THE COPPER HOARD CULTURES ARE SAID TO BE INDRA FIGURES OF ABOUT 4000 YEARS OLD • THERE ARE MANY TENS OF FIGURES IN SRAMANICAL SITE OF INDRA INCLUDING AT SANCHI (MORE THAN 6) DATABLE TO 1ST CENTURY BCE • BUT NOT A SINGLE ONE OF VISHNU INDRA 5TH CENT. CE, SARNATH PARADOXICALLY • THERE ARE 100S OF REFERENCES OF VISHNU IN THE VEDAS AND EVEN MORE SO IN THE PURANIC PERIOD • WHILE THE REFERENCE OF LAKSHMI IS VERY FEW AND FAR IN BETWEEN • CURIOUSLY THE ART OF THE SUPPOSED LAXMI FIGURES ARE MANY TIMES MORE IN EARLY HISTORIC CONTEXT EVEN IN NON VAISHNAVA CONTEXT AND IN SUCH AREAS AS THE DECCAN AND AS SOUTH AS SRI- LANKA WHICH WAS THEN UNTOUCHED BY VAISHNAVISM NW INDIA TO SRI LANKA AZILISES COIN SHOWING GAJLAKSHMI IMAGERY 70-56 ADVENT OF VAISHNAVISM VISHNU HAD BY THE STARTING OF THE COMMON ERA BEGAN TO BECOME LARGER THAN INDRA BUT FOR THE BUDDHISTS INDRA CONTINUED TO BE DEPICTED IN RELATED STORIES CONTINUED FROM EARLIER TIMES; FROM BUDDHA. -

Narasimha, the Supreme Lord of the Middle: the Avatāra and Vyūha Correlation in the Purāṇas, Archaeology and Religious Practice Lavanya Vemsani [email protected]

International Journal of Indic Religions Volume 1 | Issue 1 Article 5 10-29-2017 Narasimha, the Supreme Lord of the Middle: The Avatāra and Vyūha Correlation in the Purāṇas, Archaeology and Religious Practice Lavanya Vemsani [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.shawnee.edu/indicreligions Part of the Buddhist Studies Commons, Hindu Studies Commons, History of Religions of Eastern Origins Commons, and the South and Southeast Asian Languages and Societies Commons Recommended Citation Vemsani, Lavanya (2017) "Narasimha, the Supreme Lord of the Middle: The vA atāra and Vyūha Correlation in the Purāṇas, Archaeology and Religious Practice," International Journal of Indic Religions: Vol. 1 : Iss. 1 , Article 5. Available at: https://digitalcommons.shawnee.edu/indicreligions/vol1/iss1/5 This Research Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ Shawnee State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in International Journal of Indic Religions by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ Shawnee State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Vemsani: Narasimha, the Supreme Lord of the Middle ISBN 2471-8947 International Journal of Indic Religions Narasimha, the Supreme Lord of the Middle: The Avatāra and Vyūha Correlation in the Purāṇas, Archaeology and Religious Practice Lavanya Vemsani Ph.D. Shawnee State University [email protected] Avatāra is a theologically significant term associated with Vishnu, due to his role as protector and maintainer of balance between evil and good in the universe. Hence, each avatāra of Vishnu indicates a divinely inspired cosmic role of Vishnu. However, the incarnation of Narasimha is significant, because this incarnation is a dual representation of the God Vishnu within the creation. -

Life of Mahavira As Described in the Jai N a Gran Thas Is Imbu Ed with Myths Which

T o be h a d of 1 T HE MA A ( ) N GER , T HE mu Gu ms J , A llahaba d . Lives of greatmen all remin d u s We can m our v s su m ake li e bli e , A nd n v hi n u s , departi g , lea e be d n n m Footpri ts o the sands of ti e . NGF LL W LO E O . mm zm fitm m m ! W ‘ i fi ’ mz m n C NT E O NT S. P re face Introd uction ntrod uctor remar s and th i I y k , e h storicity of M ahavira Sources of information mt o o ica stories , y h l g l — — Family relations birth — — C hild hood e d ucation marriage and posterity — — Re nou ncing the world Distribution of wealth Sanyas — — ce re mony Ke sh alochana Re solution Seve re pen ance for twe lve years His trave ls an d pre achings for thirty ye ars Attai n me nt of Nirvan a His disciples and early followers — H is ch aracte r teachings Approximate d ate of His Nirvana Appendix A PREF CE . r HE primary con dition for th e formation of a ” Nation is Pride in a common Past . Dr . Arn old h as rightly asked How can th e presen t fru th e u u h v ms h yield it , or f t re a e pro i e , except t eir ” roots be fixed in th e past ? Smiles lays mu ch ’ s ss on h s n wh n h e s s in his h a tre t i poi t , e ay C racter, “ a ns l n v u ls v s n h an d N tio , ike i di id a , deri e tre gt su pport from the feelin g th at they belon g to an u s u s h h th e h s of h ill trio race , t at t ey are eir t eir n ss an d u h u s of h great e , o g t to be perpet ator t eir is of mm n u s im an h n glory .