Accounting Method Used by Ottomans for 500 Years: Stairs (Merdiban) Method

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

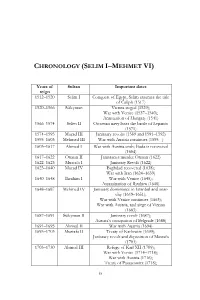

Selim I–Mehmet Vi)

CHRONOLOGY (SELIM I–MEHMET VI) Years of Sultan Important dates reign 1512–1520 Selim I Conquest of Egypt, Selim assumes the title of Caliph (1517) 1520–1566 Süleyman Vienna sieged (1529); War with Venice (1537–1540); Annexation of Hungary (1541) 1566–1574 Selim II Ottoman navy loses the battle of Lepanto (1571) 1574–1595 Murad III Janissary revolts (1589 and 1591–1592) 1595–1603 Mehmed III War with Austria continues (1595– ) 1603–1617 Ahmed I War with Austria ends; Buda is recovered (1604) 1617–1622 Osman II Janissaries murder Osman (1622) 1622–1623 Mustafa I Janissary Revolt (1622) 1623–1640 Murad IV Baghdad recovered (1638); War with Iran (1624–1639) 1640–1648 İbrahim I War with Venice (1645); Assassination of İbrahim (1648) 1648–1687 Mehmed IV Janissary dominance in Istanbul and anar- chy (1649–1651); War with Venice continues (1663); War with Austria, and siege of Vienna (1683) 1687–1691 Süleyman II Janissary revolt (1687); Austria’s occupation of Belgrade (1688) 1691–1695 Ahmed II War with Austria (1694) 1695–1703 Mustafa II Treaty of Karlowitz (1699); Janissary revolt and deposition of Mustafa (1703) 1703–1730 Ahmed III Refuge of Karl XII (1709); War with Venice (1714–1718); War with Austria (1716); Treaty of Passarowitz (1718); ix x REFORMING OTTOMAN GOVERNANCE Tulip Era (1718–1730) 1730–1754 Mahmud I War with Russia and Austria (1736–1759) 1754–1774 Mustafa III War with Russia (1768); Russian Fleet in the Aegean (1770); Inva- sion of the Crimea (1771) 1774–1789 Abdülhamid I Treaty of Küçük Kaynarca (1774); War with Russia (1787) -

Politik Penguasaan Bangsa Mongol Terhadap Negeri- Negeri Muslim Pada Masa Dinasti Ilkhan (1260-1343)

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by E-Jurnal UIN (Universitas Islam Negeri) Alauddin Makassar Politik Penguasaan Bangsa Mongol Budi dan Nita (1260-1343) POLITIK PENGUASAAN BANGSA MONGOL TERHADAP NEGERI- NEGERI MUSLIM PADA MASA DINASTI ILKHAN (1260-1343) Budi Sujati dan Nita Yuli Astuti Pascasarjana UIN Sunan Gunung Djati Bandung Email: [email protected] Abstract In the history of Islam, the destruction of the Abbasid dynasty as the center of Islamic civilization in its time that occurred on February 10, 1258 by Mongol attacks caused Islam to lose its identity.The destruction had a tremendous impact whose influence could still be felt up to now, because at that time all the evidence of Islamic relics was destroyed and burnt down without the slightest left.But that does not mean that with the destruction of Islam as a conquered religion is lost as swallowed by the earth. It is precisely with Islam that the Mongol conquerors who finally after assimilated for a long time were drawn to the end of some of the Mongol descendants themselves embraced Islam by establishing the Ilkhaniyah dynasty based in Tabriz Persia (present Iran).This is certainly the author interest in describing a unique event that the rulers themselves who ultimately follow the beliefs held by the community is different from the conquests of a nation against othernations.In this study using historical method (historical study) which is descriptive-analytical approach by using as a medium in analyzing. So that events that have happened can be known by involving various scientific methods by using social science and humanities as an approach..By using social science and humanities will be able to answer events that happened to the Mongols as rulers over the Muslim world make Islam as the official religion of his government to their grandchildren. -

Christians and Jews in Muslim Societies

Arabic and its Alternatives Christians and Jews in Muslim Societies Editorial Board Phillip Ackerman-Lieberman (Vanderbilt University, Nashville, USA) Bernard Heyberger (EHESS, Paris, France) VOLUME 5 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/cjms Arabic and its Alternatives Religious Minorities and Their Languages in the Emerging Nation States of the Middle East (1920–1950) Edited by Heleen Murre-van den Berg Karène Sanchez Summerer Tijmen C. Baarda LEIDEN | BOSTON Cover illustration: Assyrian School of Mosul, 1920s–1930s; courtesy Dr. Robin Beth Shamuel, Iraq. This is an open access title distributed under the terms of the CC BY-NC 4.0 license, which permits any non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided no alterations are made and the original author(s) and source are credited. Further information and the complete license text can be found at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/ The terms of the CC license apply only to the original material. The use of material from other sources (indicated by a reference) such as diagrams, illustrations, photos and text samples may require further permission from the respective copyright holder. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Murre-van den Berg, H. L. (Hendrika Lena), 1964– illustrator. | Sanchez-Summerer, Karene, editor. | Baarda, Tijmen C., editor. Title: Arabic and its alternatives : religious minorities and their languages in the emerging nation states of the Middle East (1920–1950) / edited by Heleen Murre-van den Berg, Karène Sanchez, Tijmen C. Baarda. Description: Leiden ; Boston : Brill, 2020. | Series: Christians and Jews in Muslim societies, 2212–5523 ; vol. -

Stjepan/Ahmed- Paša Hercegović (1456.?-1517.) U Svjetlu Dubrovačkih, Talijanskih I Osmanskih Izvora

STJEPAN/AHMED- PAšA HERCEGOVić (1456.?-1517.) U SVJETLU DUBROVAčKIH, TALIJANSKIH I OSMANSKIH IZVORA Kontroverzne teme iz života Stjepana/Ahmed-paše Hercegovića Petar VRANKIć UDK: 929.7 Stjepan/Ahmed-paša Kath.-Theologische Fakultät der Hercegović Universität Augsburg Izvorni znanstveni rad Privatadresse: Primljeno: 14. ožujka 2017. Kardinal-Brandmüller-Platz 1 Prihvaćeno: 5. travnja 2017. D - 82269 Geltendorf E-pošta: [email protected] Sažetak Knez Stjepan Hercegović Kosača, prvotno najmlađi i si- gurno najomiljeniji sin hercega Stjepana Vukčića Kosa- če, postavši kasnije Ahmed-paša Hercegović, vrlo ugled- ni i uspješni osmanski zapovjednik, upravitelj, ministar, veliki vezir, diplomat, državnik i pjesnik, ostaje i dalje djelomično kontroverzna ličnost u južnoslavenskim, ta- lijanskim i turskim povijesnim prikazima. Nije ni danas lako točno prikazati njegov životni put. Povjesnici se ne slažu u podrijetlu i imenu njegove majke, godini rođenja, slanju ili odlasku na dvor sultana Mehmeda Osvajača, sukobu s polubratom, hercegom Vlatkom, uspjelom ili neuspjelom preuzimanju oporukom utvrđenoga nasli- 9 PETAR VRANKIĆ — STJEPAN/AHMED-PAŠA HERCEGOVIĆ... jeđa njegova oca Stjepana i majke Barbare, založenog u Dubrovniku, godini ženidbe, broju žena i broju vlastite djece, te o broju i mjestu najvažnijih državnih službi iz njegova četrdesetogodišnjeg osmanskog životnog puta. U ovom prilogu autor pokušava unijeti više svjetla u gotovo sva sporna pitanja služeći se prvenstveno, danas dostu- pnim, objavljenim i neobjavljenim vrelima te dostupnom bibliografijom u arhivima i knjižnicama Dubrovnika, Venecije, Milana, Firence, Riminija, Sarajeva i Istanbula. Ključne riječi: Stjepan Hercegović/Ahmed-paša Herce- gović; herceg Stjepan; hercežica Jelena; hercežica Bar- bara; hercežica Cecilija; Dubrovnik; Carigrad; talaštvo; konverzija na islam; herceg Vlatko; sultan Mehmed II.; sultan Bajazid II.; borba za obiteljsko naslijeđe; djeca Ahmed-paše. -

The Conversion of the Jews and the Islamization of Jewish Spaces During the First Centuries of the Ottoman Empire’

BAHAR, Beki L. ‘The conversion of the Jews and the islamization of Jewish spaces during the first centuries of the Ottoman empire’. Jewish Migration: Voices of the Diaspora. Raniero Speelman, Monica Jansen & Silvia Gaiga eds. ITALIANISTICA ULTRAIECTINA 7. Utrecht : Igitur Publishing, 2012. ISBN 978‐90‐6701‐032‐0. SUMMARY This essay by the late Beki L. Behar (z.l.) focuses on conversion to Islam until the end of the Seventeenth Century. If we can speak of a privileged treatment of the Jews in the reigns of Mehmet Fatih, Bayezit II, Süleyman and Selim II – the period of Gracia Mendez and Josef Nasi –, Mehmet IV’s reign (1648‐1687) was marked by lack of tolerance and the Islamic fanatism of the fundamentalist Kadezadeli sect, in which period Jews had to face all sorts of prohibition and forced conversion, sometimes losing their living quarters. Although the Jews as inhabitants of cities rather than villages were generally not subjected to conversion and were not encouraged to enter upon the career at Court known as devşirme, an important wave of conversions initiated with Shabtai Zwi (Sabbatai Zevi), the false mashiah who preferred Islam to death penalty. His numerous followers are known in Turkish as dönmeler (dönmes). Other conversions had a less dramatic background, such as divorcing under Shari’a law or for convenience’s sake. A famous case is the court fysician Moshe ben Raphael Abravanel, who became Muslim in order to be able to practise. KEYWORDS Conversion, Shabtai Zwi, dönmes, Islamization The authors The proceedings of the international conference Jewish Migration: Voices of the Diaspora (Istanbul, June 23‐27 2010) are volume 7 of the series ITALIANISTICA ULTRAIECTINA. -

The Coins of the Later Ilkhanids

THE COINS OF THE LATER ILKHANIDS : A TYPOLOGICAL ANALYSIS 1 BY SHEILA S. BLAIR Ghazan Khan was undoubtedly the most brilliant of the Ilkhanid rulers of Persia: not only a commander and statesman, he was also a linguist, architect and bibliophile. One of his most lasting contribu- tions was the reorganization of Iran's financial system. Upon his accession to the throne, the economy was in total chaos: his prede- cessor Gaykhatf's stop-gap issue of paper money to fill an empty treasury had been a fiasco 2), and the civil wars among Gaykhatu, Baydu, and Ghazan had done nothing to restore trade or confidence in the economy. Under the direction of his vizier Rashid al-Din, Ghazan delivered an edict ordering the standardization of the coinage in weight, purity, and type 3). Ghazan's standard double-dirham became the basis of Iran's monetary system for the next century. At varying intervals, however, the standard type was changed: a new shape cartouche was introduced, with slight variations in legend. These new types were sometimes issued at a modified weight standard. This paper will analyze the successive standard issues of Ghazan and his two successors, Uljaytu and Abu Said, in order to show when and why these new types were introduced. Following a des- cription of the successive types 4), the changes will be explained through 296 an investigation of the metrology and a correlation of these changes in type with economic and political history. Another article will pursue the problem of mint organization and regionalization within this standard imperial system 5). -

Genealogy of the Concept of Securitization and Minority Rights

THE KURD INDUSTRY: UNDERSTANDING COSMOPOLITANISM IN THE TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY by ELÇIN HASKOLLAR A Dissertation submitted to the Graduate School – Newark Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Graduate Program in Global Affairs written under the direction of Dr. Stephen Eric Bronner and approved by ________________________________ ________________________________ ________________________________ ________________________________ Newark, New Jersey October 2014 © 2014 Elçin Haskollar ALL RIGHTS RESERVED ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION The Kurd Industry: Understanding Cosmopolitanism in the Twenty-First Century By ELÇIN HASKOLLAR Dissertation Director: Dr. Stephen Eric Bronner This dissertation is largely concerned with the tension between human rights principles and political realism. It examines the relationship between ethics, politics and power by discussing how Kurdish issues have been shaped by the political landscape of the twenty- first century. It opens up a dialogue on the contested meaning and shape of human rights, and enables a new avenue to think about foreign policy, ethically and politically. It bridges political theory with practice and reveals policy implications for the Middle East as a region. Using the approach of a qualitative, exploratory multiple-case study based on discourse analysis, several Kurdish issues are examined within the context of democratization, minority rights and the politics of exclusion. Data was collected through semi-structured interviews, archival research and participant observation. Data analysis was carried out based on the theoretical framework of critical theory and discourse analysis. Further, a discourse-interpretive paradigm underpins this research based on open coding. Such a method allows this study to combine individual narratives within their particular socio-political, economic and historical setting. -

March 21–25, 2016

FORTY-SEVENTH LUNAR AND PLANETARY SCIENCE CONFERENCE PROGRAM OF TECHNICAL SESSIONS MARCH 21–25, 2016 The Woodlands Waterway Marriott Hotel and Convention Center The Woodlands, Texas INSTITUTIONAL SUPPORT Universities Space Research Association Lunar and Planetary Institute National Aeronautics and Space Administration CONFERENCE CO-CHAIRS Stephen Mackwell, Lunar and Planetary Institute Eileen Stansbery, NASA Johnson Space Center PROGRAM COMMITTEE CHAIRS David Draper, NASA Johnson Space Center Walter Kiefer, Lunar and Planetary Institute PROGRAM COMMITTEE P. Doug Archer, NASA Johnson Space Center Nicolas LeCorvec, Lunar and Planetary Institute Katherine Bermingham, University of Maryland Yo Matsubara, Smithsonian Institute Janice Bishop, SETI and NASA Ames Research Center Francis McCubbin, NASA Johnson Space Center Jeremy Boyce, University of California, Los Angeles Andrew Needham, Carnegie Institution of Washington Lisa Danielson, NASA Johnson Space Center Lan-Anh Nguyen, NASA Johnson Space Center Deepak Dhingra, University of Idaho Paul Niles, NASA Johnson Space Center Stephen Elardo, Carnegie Institution of Washington Dorothy Oehler, NASA Johnson Space Center Marc Fries, NASA Johnson Space Center D. Alex Patthoff, Jet Propulsion Laboratory Cyrena Goodrich, Lunar and Planetary Institute Elizabeth Rampe, Aerodyne Industries, Jacobs JETS at John Gruener, NASA Johnson Space Center NASA Johnson Space Center Justin Hagerty, U.S. Geological Survey Carol Raymond, Jet Propulsion Laboratory Lindsay Hays, Jet Propulsion Laboratory Paul Schenk, -

Hi-Resolution Map Sheet

Controlled Mosaic of Enceladus Hamah Sulci Se 400K 43.5/315 CMN, 2018 GENERAL NOTES 66° 360° West This map sheet is the 5th of a 15-quadrangle series covering the entire surface of Enceladus at a 66° nominal scale of 1: 400 000. This map series is the third version of the Enceladus atlas and 1 270° West supersedes the release from 2010 . The source of map data was the Cassini imaging experiment (Porco et al., 2004)2. Cassini-Huygens is a joint NASA/ESA/ASI mission to explore the Saturnian 350° system. The Cassini spacecraft is the first spacecraft studying the Saturnian system of rings and 280° moons from orbit; it entered Saturnian orbit on July 1st, 2004. The Cassini orbiter has 12 instruments. One of them is the Cassini Imaging Science Subsystem 340° (ISS), consisting of two framing cameras. The narrow angle camera is a reflecting telescope with 290° a focal length of 2000 mm and a field of view of 0.35 degrees. The wide angle camera is a refractor Samad with a focal length of 200 mm and a field of view of 3.5 degrees. Each camera is equipped with a 330° 300° large number of spectral filters which, taken together, span the electromagnetic spectrum from 0.2 60° 320° 310° to 1.1 micrometers. At the heart of each camera is a charged coupled device (CCD) detector 60° consisting of a 1024 square array of pixels, each 12 microns on a side. MAP SHEET DESIGNATION Peri-Banu Se Enceladus (Saturnian satellite) 400K Scale 1 : 400 000 43.5/315 Center point in degrees consisting of latitude/west longitude CMN Controlled Mosaic with Nomenclature Duban 2018 Year of publication IMAGE PROCESSING3 Julnar Ahmad - Radiometric correction of the images - Creation of a dense tie point network 50° - Multiple least-square bundle adjustments 50° - Ortho-image mosaicking Yunan CONTROL For the Cassini mission, spacecraft position and camera pointing data are available in the form of SPICE kernels. -

Asst. Prof. ÜMİT HARUN AKKAYA

Asst. Prof. ÜMİT HARUN AKKAYA OPfefricseo Pnhaol nIen:f +or9m0 3a5t2io 6n21 7982 Extension: 42816 EFmaxa iPl:h ohanreu:n +ak9k0a 0ya3@52k a6y2s1e r7i9.e9d0u .tr AWdedbr:e hstst:p sS:e/y/raavneis Kisa.kmapysüesrüi .eBdauh.çtre/liheavrleurn Makakha. yÇaevre Yolu Cad. İslami İlimler Fakültesi No:9 38400 Develi / KAYSERİ EDodcutocraatteio, Enr cIinyefso Urnmivaetrisoityn, Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü, Philosophy and Religious Sciences, Turkey 2005 - 2016 UPonsdtegrrgardaudautaet, eE, rEcriyceiyse Us nUinveivresritsyit, yS,o İslayhaily Baitl iFmalkeürl tEenssi,t iFtüacsuül, tPyh oilfo Tshoepohlyo gayn,d T Rurekliegyio 1u9s9 S4c i-e 1n9ce9s9, Turkey 1999 - 2003 FEnogrliesihg, nB2 L Uapnpgeru Iangteersmediate Dissertations PDhoiclotosroapthey, A a nSdO CRIeOlLigOioGuYs OSFci eRnEcLeIsG, I2O0N1 6STUDY ON "MYSTERY SERIES", Erciyes University, Sosyal Bilimler Enstitüsü, KPoAsYtSgEraRdI,u Eartcei,y Ae sS TUUnDivYe rOsFit yS, OSCoIsOyLaOl BGiYli mOFle rR ELnIsGtiItOüNsü O, PNh MiloAsGoIpCh Ay NaDnd M RAeGliIgCioAuLs A SPcPieLnIcCeAsT, 2IO0N0S3 : A CASE STUDY IN RSoecsiael aSrcicehnc Aesr aenads Humanities, Theology, Sociology of Religion Academic Titles / Tasks Assistant Professor, YKoazygsaetr iB Uonziovke rUsnitiyv,e Drseivtye,l iF iasclaumltyi iOlimf Tlehre Foalokgüylt, e2s0i,1 F6e -ls 2e0fe1 9ve Din Bilimleri Bölümü , 2019 - Continues Academic and Administrative Experience -B Cöolünmtin Kuaelsite Komisyonu Üyesi, Kayseri University, Develi İslami İlimler Fakültesi, Felsefe Ve Din Bilimleri Bölümü , 2020 2B0ir1im9 -S Ctroantetijniku ePslan Komisyonu -

Mudyrd Munhal2019.Pdf

Kayseri İli Eğitim Kurumları Müdür Yardımcılığı Münhal Listesi S.No İlçe Adı Kodu Kurum Adı Münhal 1 AKKIŞLA 752374 Akkışla İmam Hatip Ortaokulu 1 2 AKKIŞLA 715468 Atatürk Ortaokulu 1 3 AKKIŞLA 715674 Derviş Çakırtekin Ortaokulu 1 4 AKKIŞLA 715995 Kululu Ortaokulu 1 5 AKKIŞLA 716155 Ortaköy Ortaokulu 1 6 AKKIŞLA 751586 Şehit Fikret Tunç Çok Programlı Anadolu Lisesi 1 7 BÜNYAN 700843 Atatürk İlkokulu 1 8 BÜNYAN 308309 Bünyan Mesleki ve Teknik Anadolu Lisesi 4 9 BÜNYAN 764076 Bünyan Sabancı Ögretmenevi ve Akşam Sanat okulu Müdürlüğü 1 10 BÜNYAN 170107 Bünyan Şehit Onur Karasungur Halk Eğitimi Merkezi 2 11 BÜNYAN 717097 Ekinciler Ortaokulu 1 12 BÜNYAN 700863 Fatih İlkokulu 1 13 BÜNYAN 751510 Güllüce İlkokulu 1 14 BÜNYAN 963201 Hamidiye Mesleki ve Teknik Anadolu Lisesi 2 15 BÜNYAN 717589 Köprübaşı Yakup Atila Ortaokulu 1 16 BÜNYAN 974311 Mehmet Alim Çınar Anaokulu 1 17 BÜNYAN 170097 Naci Baydemir Anadolu İmam Hatip Lisesi 1 18 BÜNYAN 955711 Şehit Jan. Onb. Abdi Altemel Çok Programlı Anadolu Lisesi 2 19 BÜNYAN 717998 Şehit Jandarma Er Zafer Akkaş Ortaokulu 1 20 BÜNYAN 868862 Şehit Piyade Teğmen Bekir Öztürk Çok Programlı Anadolu Lisesi 1 21 BÜNYAN 701124 Topsöğüt Ortaokulu 1 22 BÜNYAN 718148 Velioğlu Ortaokulu 1 23 DEVELİ 758363 Salih Onaran İmam Hatip Ortaokulu 1 24 DEVELİ 720615 İncesu Ortaokulu 1 25 DEVELİ 717319 Ayşepınar Ortaokulu 1 26 DEVELİ 763766 Bakırdağı Süleyman İlhan İmam Hatip Ortaokulu 1 27 DEVELİ 722422 Bakırdağı Süleyman İlhan Ortaokulu 1 28 DEVELİ 718048 Çaylıca Şehit Jandarma Er Zeki Özbek Ortaokulu 1 29 DEVELİ 748239 Develi -

The Case of Said Nursi

Loyola University Chicago Loyola eCommons Dissertations Theses and Dissertations 2015 The Dialectics of Secularism and Revivalism in Turkey: The Case of Said Nursi Zubeyir Nisanci Loyola University Chicago Follow this and additional works at: https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss Part of the Sociology Commons Recommended Citation Nisanci, Zubeyir, "The Dialectics of Secularism and Revivalism in Turkey: The Case of Said Nursi" (2015). Dissertations. 1482. https://ecommons.luc.edu/luc_diss/1482 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses and Dissertations at Loyola eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Loyola eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 3.0 License. Copyright © 2015 Zubeyir Nisanci LOYOLA UNIVERSITY CHICAGO THE DIALECTICS OF SECULARISM AND REVIVALISM IN TURKEY: THE CASE OF SAID NURSI A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY PROGRAM IN SOCIOLOGY BY ZUBEYIR NISANCI CHICAGO, ILLINOIS MAY 2015 Copyright by Zubeyir Nisanci, 2015 All rights reserved. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I am deeply grateful to Dr. Rhys H. Williams who chaired this dissertation project. His theoretical and methodological suggestions and advice guided me in formulating and writing this dissertation. It is because of his guidance that this study proved to be a very fruitful academic research and theoretical learning experience for myself. My gratitude also goes to the other members of the committee, Drs. Michael Agliardo, Laureen Langman and Marcia Hermansen for their suggestions and advice.