Waqf Endowments in the Old City of Jerusalem: Changing Status and Archival Sources

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mission Report Ref.Code: 9N15novkq0w0ggs4ogcwc8g44

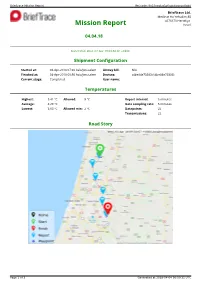

Brieftrace Mission Report Ref.code: 9n15novkq0w0ggs4ogcwc8g44 Brieftrace Ltd. Medinat Ha-Yehudim 85 4676670 Herzeliya Mission Report Israel 04.04.18 clalit Status: Success Generated: Wed, 04 Apr 18 09:50:31 +0300 Shipment Configuration Started at: 04-Apr-2018 07:30 Asia/Jerusalem Airway bill: N/A Finished at: 04-Apr-2018 09:50 Asia/Jerusalem Devices: c4be84e73383 (c4be84e73383) Current stage: Completed User name: Shai Temperatures Highest: 5.41 °C Allowed: 8 °C Report interval: 5 minutes Average: 4.29 °C Data sampling rate: 5 minutes Lowest: 3.63 °C Allowed min: 2 °C Datapoints: 22 Transmissions: 22 Road Story Page 1 of 3 Generated at 2018-04-04 06:50:31 UTC Brieftrace Mission Report Ref.code: 9n15novkq0w0ggs4ogcwc8g44 Report Data 13 ° 12 ° 11 ° 10 ° 9 ° Allowed high: 8° C 8 ° C 7 ° ° High e r 6 ° Max: 5.41° C u t a 5 ° r Low e p 4 ° Min: 3.63° C m e 3 ° T Allowed low: 2° C 2 ° 1 ° 0 ° -1 ° -2 ° -3 ° 07:30 07:45 08:00 08:15 08:30 08:45 09:00 09:15 09:30 09:45 Date and time. All times are in Asia/Jerusalem timezone. brieftrace.com Tracker Time Date Temp°CAlert? RH % Location Control Traceability c4be84e73383 07:30 04-04-2018 4.26 79.65 Ha-Matekhet St 17, Kadima Zoran, Israel 636158 dfb902 c4be84e73383 07:36 04-04-2018 4.24 79.75 Ha-Matekhet St 17, Kadima Zoran, Israel 636161 b23bc8 c4be84e73383 07:43 04-04-2018 4.21 79.75 Ha-Matekhet St 17, Kadima Zoran, Israel 636167 c1c01c c4be84e73383 07:49 04-04-2018 4.18 79.85 Ha-Matekhet St 17, Kadima Zoran, Israel 636176 4a3752 c4be84e73383 07:56 04-04-2018 4.21 79.85 Ha-Matekhet St 17, Kadima -

Israel National Report for Habitat III National Israel Report

Israel National Report for Habitat III National Report Israel National | 1 Table of content: Israel National Report for Habitat III Forward 5-6 I. Urban Demographic Issues and Challenges for a New Urban Agenda 7-15 1. Managing rapid urbanization 7 2. Managing rural-urban linkages 8 3. Addressing urban youth needs 9 4. Responding to the needs of the aged 11 5. Integrating gender in urban development 12 6. Challenges Experienced and Lessons Learned 13 II. Land and Urban Planning: Issues and Challenges for a New Urban Agenda 16-22 7. Ensuring sustainable urban planning and design 16 8. Improving urban land management, including addressing urban sprawl 17 9. Enhancing urban and peri-urban food production 18 10. Addressing urban mobility challenges 19 11. Improving technical capacity to plan and manage cities 20 Contributors to this report 12. Challenges Experienced and Lessons Learned 21 • National Focal Point: Nethanel Lapidot, senior division of strategic planing and policy, Ministry III. Environment and Urbanization: Issues and Challenges for a New Urban of Construction and Housing Agenda 23-29 13. Climate status and policy 23 • National Coordinator: Hofit Wienreb Diamant, senior division of strategic planing and policy, Ministry of Construction and Housing 14. Disaster risk reduction 24 • Editor: Dr. Orli Ronen, Porter School for the Environment, Tel Aviv University 15. Minimizing Transportation Congestion 25 • Content Team: Ayelet Kraus, Ira Diamadi, Danya Vaknin, Yael Zilberstein, Ziv Rotem, Adva 16. Air Pollution 27 Livne, Noam Frank, Sagit Porat, Michal Shamay 17. Challenges Experienced and Lessons Learned 28 • Reviewers: Dr. Yodan Rofe, Ben Gurion University; Dr. -

The Mughrabi Quarter Digital Archive and the Virtual Illés Relief Initiative

Are you saying there’s an original sin? The Mughrabi True, there is. Deal with it. Quarter Digital – Meron Benvenisti (2013) Archive and the Few spaces are more emblematic of Jerusalem today than the Western Virtual Illés Relief Wall Plaza, yet few people – including Initiative Palestinian and Israeli residents of Jerusalem alike – are aware of the Maryvelma Smith O’Neil destruction of the old Mughrabi Quarter that literally laid the groundwork for its very creation. For the longue durée of almost eight centuries, the Mughrabi Quarter of Jerusalem had been home to Arabs from North Africa, Andalusia, and Palestine. However, within two days after the 1967 War (10–12 June 1967), the historic neighborhood, located in the city’s southeast corner near the western wall of the Noble Sanctuary (al-Haram al-Sharif), was completely wiped off the physical map by the State of Israel – in flagrant violation of Article 53 of the Fourth Geneva Convention, which stipulates: Any destruction by the Occupying Power of real or personal property belonging individually or collectively to private persons, or to the State, or to other public authorities, or to social or cooperative organizations, is prohibited, except where such destruction is rendered absolutely necessary by military operations.1 Two decades prior to the Mughrabi Quarter demolition, Jerusalem’s designation as a “corpus separatum” had been intended to depoliticize the city through internationalization, under [ 52 ] Mughrabi Quarter & Illés Relief Initiative | Maryvelma Smith O’Neil Figure 1. Vue Générale de la Mosquée d’Omar, Robertson, Beato & Co., 1857. Photo: National Science and Society Picture Library. -

The Judaization of Jerusalem/Al-Quds

Published by Americans for The Link Middle East Understanding, Inc. Volume 51, Issue 4 Link Archives: www.ameu.org September-October 2018 The Judaization of Jerusalem/Al-Quds by Basem L. Ra'ad About This Issue: Basem Ra’ad is a professor emeritus at Al-Quds University in Jerusalem. This is his second feature article for The Link; his first, “Who Are The Ca- naanites’? Why Ask?,” appeared in our December, 2011 issue. John F. Mahoney, Executive Director The Link Page 2 The Judaization of Jerusalem / Al-Quds Board of Directors by Basem L. Ra'ad Jane Adas, President Elizabeth D. Barlow Edward Dillon Henrietta Goelet John Goelet At last year’s Toronto Palestinian Film Festival, I attended a session Richard Hobson, Treasurer entitled “Jerusalem, We Are Here,” described as an interactive tour of 1948 Anne R. Joyce, Vice President West Jerusalem. It was designed by a Canadian-Israeli academic specifically Janet McMahon as a virtual excursion into the Katamon and Baqʿa neighborhoods, inhabited John F. Mahoney, Ex. Director by Christian and Muslim Palestinian families before the Nakba — in Darrel D.Meyers English, the Catastrophe. Brian Mulligan Daniel Norton Little did I anticipate the painful memories this session would bring. Thomas Suárez The tour starts in Katamon at an intersec- James M. Wall tion that led up to the Semiramis Hotel. The hotel was blown up by the Haganah President-Emeritus on the night of 5-6 January 1948, killing 25 Robert L. Norberg civilians, and was followed by other at- National Council tacks intended to vacate non-Jewish citi- Kathleen Christison zens from the western part of the city. -

2009 High School in University! Shachar Jerusalem and Is a Ninth Grader Is Sponsored by at the Menachem the NACOEJ/EDWARD G

Sponsorships Encourage Students to Develop Their Potential Sponsorships give Ethiopian students the chance to gain the most out of school. In some cases, students’ talents become a gift for everyone! The outstanding examples below help us understand how valuable your contributions are. Sara Shachar Zisanu Baruch attends the Dror has a head start on SUMMER 2009 High School in university! Shachar Jerusalem and is a ninth grader is sponsored by at the Menachem THE NACOEJ/EDWARD G. VICTOR HIGH SCHOOL SPONSORSHIP PROGRAM Marsha Croland Begin High School of White Plains, in Ness Ziona. In NY. Sara has just fi fth grade, he took fi nished eleventh a mathematics course by correspondence Sponsors grade and is ac- through the Weizmann Institute for Sci- tive as a counselor in the youth move- ence. Since then, he has been taking ment HaShomer Hatzair, affi liated with special courses in math and science, won Give and the kibbutz movement. Sara has been a fi rst-place in the Municipal Bible contest member of the group since she was nine in sixth grade, and took second-place in years old and was encouraged to become a the Municipal Battlefi eld Heritage Con- Ethiopian counselor by her own counselor last year. test (a quiz on Israeli military history) Sara appreciates the values of teamwork, in seventh grade! Currently, Shachar is in independence, and positive communica- an advanced program for math at Bar Ilan Students tion that she has learned in the move- University and takes math and science ment. As a counselor of fourth graders, courses at Tel Aviv University. -

A Guide to Al-Aqsa Mosque Al-Haram Ash-Sharif Contents

A Guide to Al-Aqsa Mosque Al-Haram Ash-Sharif Contents In the name of Allah, most compassionate, most merciful Introduction JJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJ<<<<3 Dear Visitor, Mosques JJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJ<<<<<4 Welcome to one of the major Islamic sacred sites and landmarks Domes JJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJ<<<24 of civilization in Jerusalem, which is considered a holy city in Islam because it is the city of the prophets. They preached of the Minarets JJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJ<<<30 Messenger of God, Prophet Mohammad (PBUH): Arched Gates JJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJ<<<32 The Messenger has believed in what was revealed to him from his Lord, and [so have] the believers. All of them have believed in Allah and His angels and Schools JJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJ<<<36 His books and His messengers, [saying], “We make no distinction between any of His messengers.” And they say, “We hear and we obey. [We seek] Your Corridors JJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJ<<<<44 forgiveness, our Lord, and to You is the [final] destination” (Qur’an 2:285). Gates JJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJ<<<<46 It is also the place where one of Prophet Mohammad’s miracles, the Night Journey (Al-Isra’ wa Al-Mi’raj), took place: Water Sources JJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJJ<<<54 Exalted is He who took His Servant -

Graduate Affairs Committee January 27, 2004 3:30 P.M

Graduate Affairs Committee January 27, 2004 3:30 p.m. - 5:00 p.m. UL 1126 AGENDA 1. Approval of the minutes for November 25, 2003 .................................................... Queener 2. Associate Dean’s Report .......................................................................................... Queener 3. Purdue Dean’s Report ................................................................................................... Story 4. Graduate Office Report ............................................................................................ Queener 5. Committee Business a. Curriculum Subcommittee ........................................................................... O’Palka 6. International Affairs a. IELTS vs. TOEFL ............................................................................................ Allaei 7. Program Approval .................................................................................................... Queener a. M.S. Health Sciences Education – Name Change b. M.A. in Political Science c. M.S. in Music Therapy 8. Discussion ................................................................................................................ Queener a. MSD Thesis Optional b. Joint Ph.D. in Electrical and Computer Engineering 9. New Business…………………………………… 10. Next Meeting (February 24) and adjournment Graduate Affairs Committee January 27, 2004 Minutes Present: William Bosron, Mark Brenner (co-chair), Ain Haas, Dolores Hoyt, Andrew Hsu, Jane Lambert, Joyce MacKinnon, Jackie O’Palka, Douglas -

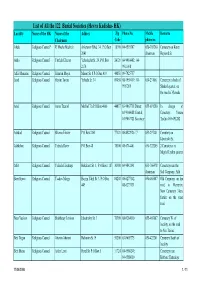

List of All the 122 Burial Societies (Hevra Kadisha- HK) Locality Name of the HK Name of the Addres Zip Phone No

List of All the 122 Burial Societies (Hevra Kadisha- HK) Locality Name of the HK Name of the Addres Zip Phone No. Mobile Remarks Chairman Code phone no. Afula Religious Council* R' Moshe Mashiah Arlozorov Blvd. 34, P.O.Box 18100 04-6593507 050-303260 Cemetery on Keren 2041 chairman Hayesod St. Akko Religious Council Yitzhak Elharar Yehoshafat St. 29, P.O.Box 24121 04-9910402; 04- 2174 9911098 Alfei Menashe Religious Council Shim'on Moyal Manor St. 8 P.O.Box 419 44851 09-7925757 Arad Religious Council Hayim Tovim Yehuda St. 34 89058 08-9959419; 08- 050-231061 Cemetery in back of 9957269 Shaked quarter, on the road to Massada Ariel Religious Council Amos Tzuriel Mish'ol 7/a P.O.Box 4066 44837 03-9067718 Direct; 055-691280 In charge of 03-9366088 Central; Cemetery: Yoram 03-9067721 Secretary Tzefira 055-691282 Ashdod Religious Council Shlomo Eliezer P.O.Box 2161 77121 08-8522926 / 7 053-297401 Cemetery on Jabotinski St. Ashkelon Religious Council Yehuda Raviv P.O.Box 48 78100 08-6714401 050-322205 2 Cemeteries in Migdal Tzafon quarter Atlit Religious Council Yehuda Elmakays Hakalanit St. 1, P.O.Box 1187 30300 04-9842141 053-766478 Cemetery near the chairman Salt Company, Atlit Beer Sheva Religious Council Yaakov Margy Hayim Yahil St. 3, P.O.Box 84208 08-6277142, 050-465887 Old Cemetery on the 449 08-6273131 road to Harzerim; New Cemetery 3 km. further on the same road Beer Yaakov Religious Council Shabbetay Levison Jabotinsky St. 3 70300 08-9284010 055-465887 Cemetery W. -

The Israeli Occupation of Jerusalem

77 The Suffering of Jerusalem Am I not a Human? and the Holy Sites (7) under the Israeli Occupation Book series discussing the sufferance of the Palestinian people under the Israeli By occupation Dr. Mohsen Moh’d Saleh Research Assistant Fatima ‘Itani English Version Translated by Edited by Salma al-Houry Dr. Mohsen Moh’d Saleh Rana Sa‘adah Al-Zaytouna Centre Al-Quds International Institution (QII) For Studies & Consultations www.alquds-online.org �سل�سلة “�أول�ست �إن�ساناً؟” (7) معاناة �لقد�س و�ملقد�سات حتت �لحتالل �لإ�رس�ئيلي Prepared by: Dr. Mohsen Moh’d Saleh English Version: Edited by: Dr. Mohsen Moh’d Saleh & Rana Sa‘adah Translated by: Salma al-Houry First published 2012 Al-Zaytouna Centre for Al-Quds International Institution (QII) Studies & Consultations P.O.Box: 14-5034, Beirut, Lebanon Beirut, Lebanon Tel: + 961 1 803 644 Tel: + 961 1 751 725 Tel-fax: + 961 1 803 643 Fax: + 961 1 751 726 Email: [email protected] Website: www.alzaytouna.net Website: www.alquds-online.org ISBN 978-9953-500-55-3 © All rights reserved to al-Zaytouna Centre for Studies & Consultations. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher. For further information regarding permission(s), please write to: [email protected] The views expressed in this book are those of the authors alone. They do not necessarily reflect views of al-Zaytouna Centre for Studies and Consultations and al-Quds International Institution (QII). -

Arab Scholars and Ottoman Sunnitization in the Sixteenth Century 31 Helen Pfeifer

Historicizing Sunni Islam in the Ottoman Empire, c. 1450–c. 1750 Islamic History and Civilization Studies and Texts Editorial Board Hinrich Biesterfeldt Sebastian Günther Honorary Editor Wadad Kadi volume 177 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/ihc Historicizing Sunni Islam in the Ottoman Empire, c. 1450–c. 1750 Edited by Tijana Krstić Derin Terzioğlu LEIDEN | BOSTON This is an open access title distributed under the terms of the CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 license, which permits any non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided no alterations are made and the original author(s) and source are credited. Further information and the complete license text can be found at https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ The terms of the CC license apply only to the original material. The use of material from other sources (indicated by a reference) such as diagrams, illustrations, photos and text samples may require further permission from the respective copyright holder. Cover illustration: “The Great Abu Sa’ud [Şeyhü’l-islām Ebū’s-suʿūd Efendi] Teaching Law,” Folio from a dīvān of Maḥmūd ‘Abd-al Bāqī (1526/7–1600), The Metropolitan Museum of Art. The image is available in Open Access at: https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/447807 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Krstić, Tijana, editor. | Terzioğlu, Derin, 1969- editor. Title: Historicizing Sunni Islam in the Ottoman Empire, c. 1450–c. 1750 / edited by Tijana Krstić, Derin Terzioğlu. Description: Boston : Brill, 2020. | Series: Islamic history and civilization. studies and texts, 0929-2403 ; 177 | Includes bibliographical references and index. -

Israel (Includes West Bank and Gaza) 2020 International Religious Freedom Report

ISRAEL (INCLUDES WEST BANK AND GAZA) 2020 INTERNATIONAL RELIGIOUS FREEDOM REPORT Executive Summary The country’s laws and Supreme Court rulings protect the freedoms of conscience, faith, religion, and worship, regardless of an individual’s religious affiliation. The 1992 Basic Law: Human Dignity and Liberty describes the country as a “Jewish and democratic state.” The 2018 Basic Law: Israel – The Nation State of the Jewish People law determines, according to the government, that “the Land of Israel is the historical homeland of the Jewish people; the State of Israel is the nation state of the Jewish People, in which it realizes its natural, cultural, religious and historical right to self-determination; and exercising the right to national self- determination in the State of Israel is unique to the Jewish People.” In June, authorities charged Zion Cohen for carrying out attacks on May 17 on religious institutions in Petah Tikva, Ashdod, Tel Aviv, and Kfar Saba. According to his indictment, Cohen sought to stop religious institutions from providing services to secular individuals, thereby furthering his goal of separating religion and the state. He was awaiting trial at year’s end. In July, the Haifa District Court upheld the 2019 conviction and sentencing for incitement of Raed Salah, head of the prohibited Islamic Movement, for speaking publicly in favor an attack by the group in 2017 that killed two police officers at the Haram al-Sharif/Temple Mount. In his defense, Salah stated that his views were religious opinions rooted in the Quran and that they did not include a direct call to violence. -

The Haram Al-Sharif at the Eye of the Storm Ethno-Geographical and Diverse Religious Landscape of Jerusalem

Editorial Writing on “Five Decades of Subjection and Marginalization” of Palestinians in Jerusalem The Haram in the previous issue of Jerusalem Quarterly (62), historian and Jerusalemite Nazmi Jubeh al-Sharif at the Eye warned of increasing Israeli control over of the Storm access to the al-Aqsa/Dome of the Rock mosque compound – the Haram al-Sharif or Noble Sanctuary – including the pattern of provocative “visits” by Israeli right-wing activists and politicians, accompanied by police and border guards. The Noble Sanctuary is “one of the last remaining Palestinian strongholds in Jerusalem and the embodiment of many religious and national symbols.” At present, Jubeh presciently added, it is a “powder keg.” As we go to press, in mid-November, clashes at the Haram al-Sharif that erupted when armed Israeli police entered the mosque compound a month earlier in the wake of a visit by far-right Israeli Minister Uri Ariel have spread throughout Jerusalem neighborhoods and refugee camps, villages and towns in the rest of the occupied West Bank and along the Gaza border, as well as inside Israel itself. All that can be said with certainty is that Palestinian protest over Israeli actions at the Haram al-Sharif was inevitable, that the direction and duration of the conflict is unpredictable, and that the surge of Palestinian protest is fueled by Israeli actions at the Haram, but embraces the multiple violations of Palestinian rights and lives. Commentators appear fixated on whether to label the present events a “third intifada” rather than addressing the fundamental issues of the denial of rights to Palestinians in Jerusalem, the continuing occupation of Palestine, and Israeli refusal to negotiate a just peace.