Limits to Arbitrage and Commodity Index Investment: Front-Running the Goldman Roll

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Equity Trading in the 21St Century

Equity Trading in the 21st Century February 23, 2010 James J. Angel Associate Professor McDonough School of Business Georgetown University Lawrence E. Harris Fred V. Keenan Chair in Finance Professor of Finance and Business Economics Marshall School of Business University of Southern California Chester S. Spatt Pamela R. and Kenneth B. Dunn Professor of Finance Director, Center for Financial Markets Tepper School of Business Carnegie Mellon University 1. Introduction1 Trading in financial markets changed substantially with the growth of new information processing and communications technologies over the last 25 years. Electronic technologies profoundly altered how exchanges, brokers, and dealers arrange most trades. In some cases, innovative trading systems are so different from traditional ones that many political leaders and regulators do not fully appreciate how they work and the many benefits that they offer to investors and to the economy as a whole. In the face of incomplete knowledge about this evolving environment, some policymakers now question whether these innovations are in the public interest. Technical jargon such as “dark liquidity pools,” “hidden orders,” “flickering quotes,” and “flash orders” appear ominous to those not familiar with the objects being described. While professional traders measure system performance in milliseconds, others wonder what possible difference seconds—much less milliseconds—could have on capital formation within our economy. The ubiquitous role of computers in trading systems makes many people nervous, and especially those who remember the 1987 Stock Market Crash and how the failure of exchange trading systems exacerbated problems caused by traders following computer-generated trading strategies. Strikingly, the mechanics of the equity markets functioned very well during the financial crisis, despite the widespread use of computerized trading. -

Here We Go Again

2015, 2016 MDDC News Organization of the Year! Celebrating 161 years of service! Vol. 163, No. 3 • 50¢ SINCE 1855 July 13 - July 19, 2017 TODAY’S GAS Here we go again . PRICE Rockville political differences rise to the surface in routine commission appointment $2.28 per gallon Last Week pointee to the City’s Historic District the three members of “Team him from serving on the HDC. $2.26 per gallon By Neal Earley @neal_earley Commission turned into a heated de- Rockville,” a Rockville political- The HDC is responsible for re- bate highlighting the City’s main po- block made up of Council members viewing applications for modification A month ago ROCKVILLE – In most jurisdic- litical division. Julie Palakovich Carr, Mark Pierzcha- to the exteriors of historic buildings, $2.36 per gallon tions, board and commission appoint- Mayor Bridget Donnell Newton la and Virginia Onley who ran on the as well as recommending boundaries A year ago ments are usually toward the bottom called the City Council’s rejection of same platform with mayoral candi- for the City’s historic districts. If ap- $2.28 per gallon of the list in terms of public interest her pick for Historic District Commis- date Sima Osdoby and city council proved Giammo, would have re- and controversy -- but not in sion – former three-term Rockville candidate Clark Reed. placed Matthew Goguen, whose term AVERAGE PRICE PER GALLON OF Rockville. UNLEADED REGULAR GAS IN Mayor Larry Giammo – political. While Onley and Palakovich expired in May. MARYLAND/D.C. METRO AREA For many municipalities, may- “I find it absolutely disappoint- Carr said they opposed Giammo’s ap- Giammo previously endorsed ACCORDING TO AAA oral appointments are a formality of- ing that politics has entered into the pointment based on his lack of qualifi- Newton in her campaign against ten given rubberstamped approval by boards and commission nomination cations, Giammo said it was his polit- INSIDE the city council, but in Rockville what process once again,” Newton said. -

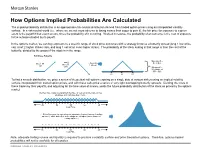

How Options Implied Probabilities Are Calculated

No content left No content right of this line of this line How Options Implied Probabilities Are Calculated The implied probability distribution is an approximate risk-neutral distribution derived from traded option prices using an interpolated volatility surface. In a risk-neutral world (i.e., where we are not more adverse to losing money than eager to gain it), the fair price for exposure to a given event is the payoff if that event occurs, times the probability of it occurring. Worked in reverse, the probability of an outcome is the cost of exposure Place content to the outcome divided by its payoff. Place content below this line below this line In the options market, we can buy exposure to a specific range of stock price outcomes with a strategy know as a butterfly spread (long 1 low strike call, short 2 higher strikes calls, and long 1 call at an even higher strike). The probability of the stock ending in that range is then the cost of the butterfly, divided by the payout if the stock is in the range. Building a Butterfly: Max payoff = …add 2 …then Buy $5 at $55 Buy 1 50 short 55 call 1 60 call calls Min payoff = $0 outside of $50 - $60 50 55 60 To find a smooth distribution, we price a series of theoretical call options expiring on a single date at various strikes using an implied volatility surface interpolated from traded option prices, and with these calls price a series of very tight overlapping butterfly spreads. Dividing the costs of these trades by their payoffs, and adjusting for the time value of money, yields the future probability distribution of the stock as priced by the options market. -

Tax Treatment of Derivatives

United States Viva Hammer* Tax Treatment of Derivatives 1. Introduction instruments, as well as principles of general applicability. Often, the nature of the derivative instrument will dictate The US federal income taxation of derivative instruments whether it is taxed as a capital asset or an ordinary asset is determined under numerous tax rules set forth in the US (see discussion of section 1256 contracts, below). In other tax code, the regulations thereunder (and supplemented instances, the nature of the taxpayer will dictate whether it by various forms of published and unpublished guidance is taxed as a capital asset or an ordinary asset (see discus- from the US tax authorities and by the case law).1 These tax sion of dealers versus traders, below). rules dictate the US federal income taxation of derivative instruments without regard to applicable accounting rules. Generally, the starting point will be to determine whether the instrument is a “capital asset” or an “ordinary asset” The tax rules applicable to derivative instruments have in the hands of the taxpayer. Section 1221 defines “capital developed over time in piecemeal fashion. There are no assets” by exclusion – unless an asset falls within one of general principles governing the taxation of derivatives eight enumerated exceptions, it is viewed as a capital asset. in the United States. Every transaction must be examined Exceptions to capital asset treatment relevant to taxpayers in light of these piecemeal rules. Key considerations for transacting in derivative instruments include the excep- issuers and holders of derivative instruments under US tions for (1) hedging transactions3 and (2) “commodities tax principles will include the character of income, gain, derivative financial instruments” held by a “commodities loss and deduction related to the instrument (ordinary derivatives dealer”.4 vs. -

Bond Futures Calendar Spread Trading

Black Algo Technologies Bond Futures Calendar Spread Trading Part 2 – Understanding the Fundamentals Strategy Overview Asset to be traded: Three-month Canadian Bankers' Acceptance Futures (BAX) Price chart of BAXH20 Strategy idea: Create a duration neutral (i.e. market neutral) synthetic asset and trade the mean reversion The general idea is straightforward to most professional futures traders. This is not some market secret. The success of this strategy lies in the execution. Understanding Our Asset and Synthetic Asset These are the prices and volume data of BAX as seen in the Interactive Brokers platform. blackalgotechnologies.com Black Algo Technologies Notice that the volume decreases as we move to the far month contracts What is BAX BAX is a future whose underlying asset is a group of short-term (30, 60, 90 days, 6 months or 1 year) loans that major Canadian banks make to each other. BAX futures reflect the Canadian Dollar Offered Rate (CDOR) (the overnight interest rate that Canadian banks charge each other) for a three-month loan period. Settlement: It is cash-settled. This means that no physical products are transferred at the futures’ expiry. Minimum price fluctuation: 0.005, which equates to C$12.50 per contract. This means that for every 0.005 move in price, you make or lose $12.50 Canadian dollar. Link to full specification details: • https://m-x.ca/produits_taux_int_bax_en.php (Note that the minimum price fluctuation is 0.01 for contracts further out from the first 10 expiries. Not too important as we won’t trade contracts that are that far out.) • https://www.m-x.ca/f_publications_en/bax_en.pdf Other STIR Futures BAX are just one type of short-term interest rate (STIR) future. -

Gibson, Christopher M

~-1;'· / r :r-- - UNITED STATES OF AMERICA RECEIVED Before the JUN 1 9 2017 SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 OFFICE OF THE SECRE Administrative Proceeding File No. 3-17184 In the Matter of CHRISTOPHER M. GIBSON, Respondent. DIVISION OF ENFORCEMENT'S OPPOSITION BRIEF June 19, 2017 H. Michael Semler Gregory R. Boclcin Paul J. Bohr George J. Bagnall U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission Division of Enforcement 100 F Street, N .E. Washington, D.C. 20549 Counsel for Division of Enforcement r > Table of Contents INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................. 1 THE EVIDENTIARY RECORD .......................................................................................... 1 THE INITIAL DECISION................................................................................................... 11 ARGUMENT ........................................................................................................................ 13 I. GIBSON VIOLATED SECTIONS 206(1) AND (2) OF THE ADVISORS ACT......... 13 A. Gibson Was An Investment Adviser Subject To Section 206 ............................ 13 1. Investors Were Told That Gibson Would Manage The Fund's Investments And Gibson Did So ................................................................... 14 2. Gibson Was An Investment Adviser Even If He Acted In The Name Of Geier Capital................................................................................. 15 3. Gibson Was an Investment -

Informational Inequality: How High Frequency Traders Use Premier Access to Information to Prey on Institutional Investors

INFORMATIONAL INEQUALITY: HOW HIGH FREQUENCY TRADERS USE PREMIER ACCESS TO INFORMATION TO PREY ON INSTITUTIONAL INVESTORS † JACOB ADRIAN ABSTRACT In recent months, Wall Street has been whipped into a frenzy following the March 31st release of Michael Lewis’ book “Flash Boys.” In the book, Lewis characterizes the stock market as being rigged, which has institutional investors and outside observers alike demanding some sort of SEC action. The vast majority of this criticism is aimed at high-frequency traders, who use complex computer algorithms to execute trades several times faster than the blink of an eye. One of the many complaints against high-frequency traders is over parasitic trading practices, such as front-running. Front-running, in the era of high-frequency trading, is best defined as using the knowledge of a large impending trade to take a favorable position in the market before that trade is executed. Put simply, these traders are able to jump in front of a trade before it can be completed. This Note explains how high-frequency traders are able to front- run trades using superior access to information, and examines several proposed SEC responses. INTRODUCTION If asked to envision what trading looks like on the New York Stock Exchange, most people who do not follow the U.S. securities market would likely picture a bunch of brokers standing around on the trading floor, yelling and waving pieces of paper in the air. Ten years ago they would have been absolutely right, but the stock market has undergone radical changes in the last decade. It has shifted from one dominated by manual trading at a physical location to a vast network of interconnected and automated trading systems.1 Technological advances that simplified how orders are generated, routed, and executed have fostered the changes in market † J.D. -

Intraday Volatility Surface Calibration

INTRADAY VOLATILITY SURFACE CALIBRATION Master Thesis Tobias Blomé & Adam Törnqvist Master thesis, 30 credits Department of Mathematics and Mathematical Statistics Spring Term 2020 Intraday volatility surface calibration Adam T¨ornqvist,[email protected] Tobias Blom´e,[email protected] c Copyright by Adam T¨ornqvist and Tobias Blom´e,2020 Supervisors: Jonas Nyl´en Nasdaq Oskar Janson Nasdaq Xijia Liu Department of Mathematics and Mathematical Statistics Examiner: Natalya Pya Arnqvist Department of Mathematics and Mathematical Statistics Master of Science Thesis in Industrial Engineering and Management, 30 ECTS Department of Mathematics and Mathematical Statistics Ume˚aUniversity SE-901 87 Ume˚a,Sweden i Abstract On the financial markets, investors search to achieve their economical goals while simultaneously being exposed to minimal risk. Volatility surfaces are used for estimating options' implied volatilities and corresponding option prices, which are used for various risk calculations. Currently, volatility surfaces are constructed based on yesterday's market in- formation and are used for estimating options' implied volatilities today. Such a construction gets redundant very fast during periods of high volatility, which leads to inaccurate risk calculations. With an aim to reduce volatility surfaces' estimation errors, this thesis explores the possibilities of calibrating volatility surfaces intraday using incomplete mar- ket information. Through statistical analysis of the volatility surfaces' historical movements, characteristics are identified showing sections with resembling mo- tion patterns. These insights are used to adjust the volatility surfaces intraday. The results of this thesis show that calibrating the volatility surfaces intraday can reduce the estimation errors significantly during periods of both high and low volatility. -

How to Become A

GUIDE TO BECOMING A COMMODITY TRADING ADVISOR Guide to Becoming a CTA Dean E. Lundell © Copyright 2004 Chicago Mercantile Exchange Guide to Becoming a CTA 1 TABLE OF CONTENTS 5 Acknowledgements Chapter One 7 Market Trends for Alternative Investments Chapter Two 9 The Business of Being a CTA Business Plan and Structure Staffing Growth Management Office Equipment and Trading Systems Start-Up Costs Brokerage Firms and Commission Rates Commissions and Clients Execution Services Professional Services Chapter Three 15 Creating Your Trading Product Overview Mechanical Systems Discretionary Strategies Diversified Strategies Single Sector Strategies Strategy Design and Testing Slippage Control Institutional vs. Retail Investors Chapter Four 23 Marketing Your CTA Business Track Record Raising Funds Account Sizes Professional Money Raisers Client Relationships National Futures Association Rules Chapter Five 31 The Measures of CTA Success Performance and Consistency of Returns Limiting Drawdowns Length of Track Record Becoming Established Rates of Growth 2 Guide to Becoming a CTA Chapter Six 35 Risk Management for CTAs Diversification Risk per Trade Position Sizes and Risk Exposure Trading in Units Kick-Out Levels Volatility Measurement and Control Margin-to-Equity Ratio Commission-to-Equity Ratio Stop Orders Common Questions Chapter Seven 43 CTA Performance Records Regulatory Requirements Proprietary Performance Record Simulated or Hypothetical Reports Composite Performance Records Rate of Return Calculations Establishing Your Performance Record -

GS&Co. Disclosure Regarding FINRA Rule 5270

GOLDMAN SACHS & Co. LLC (“GS&Co.”) Prohibition on Front Running Client Block Transactions FINRA Rule 5270 prohibits a broker-dealer from trading for its own account while taking advantage of material, non-public market information concerning an imminent block transaction in a security, a related financial instrument1 or a security underlying the related financial instrument prior to the time information concerning the block transaction has been made publicly available or has otherwise become stale or obsolete. GS&Co. employees are strictly prohibited from engaging in activity that violates Rule 5270. The Rule provides exceptions to the general prohibition for certain transactions. For example, the Rule does not preclude a broker-dealer from trading for its own account for purpose of fulfilling or facilitating the execution of a client’s block transaction. A broker- dealer is also permitted to engage in hedging or pre-hedging when the purpose of the trading is to fulfill the client order and the broker-dealer has disclosed such trading activity to the client. This hedging or pre-hedging activity may coincidentally impact the market prices of the securities or financial instruments a client is buying or selling. As always, GS&Co. conducts this trading in a manner designed to limit market impact and consistent with its best execution obligations. 1 For purposes of this Rule, the term "related financial instrument" means any option, derivative, security-based swap, or other financial instrument overlying a security, the value of which is materially related to, or otherwise acts as a substitute for, such security, as well as any contract that is the functional economic equivalent of a position in such security. -

Binomial Trees • Stochastic Calculus, Ito’S Rule, Brownian Motion • Black-Scholes Formula and Variations • Hedging • Fixed Income Derivatives

Pricing Options with Mathematical Models 1. OVERVIEW Some of the content of these slides is based on material from the book Introduction to the Economics and Mathematics of Financial Markets by Jaksa Cvitanic and Fernando Zapatero. • What we want to accomplish: Learn the basics of option pricing so you can: - (i) continue learning on your own, or in more advanced courses; - (ii) prepare for graduate studies on this topic, or for work in industry, or your own business. • The prerequisites we need to know: - (i) Calculus based probability and statistics, for example computing probabilities and expected values related to normal distribution. - (ii) Basic knowledge of differential equations, for example solving a linear ordinary differential equation. - (iii) Basic programming or intermediate knowledge of Excel • A rough outline: - Basic securities: stocks, bonds - Derivative securities, options - Deterministic world: pricing fixed cash flows, spot interest rates, forward rates • A rough outline (continued): - Stochastic world, pricing options: • Pricing by no-arbitrage • Binomial trees • Stochastic Calculus, Ito’s rule, Brownian motion • Black-Scholes formula and variations • Hedging • Fixed income derivatives Pricing Options with Mathematical Models 2. Stocks, Bonds, Forwards Some of the content of these slides is based on material from the book Introduction to the Economics and Mathematics of Financial Markets by Jaksa Cvitanic and Fernando Zapatero. A Classification of Financial Instruments SECURITIES AND CONTRACTS BASIC SECURITIES DERIVATIVES -

Consolidated Policy on Valuation Adjustments Global Capital Markets

Global Consolidated Policy on Valuation Adjustments Consolidated Policy on Valuation Adjustments Global Capital Markets September 2008 Version Number 2.35 Dilan Abeyratne, Emilie Pons, William Lee, Scott Goswami, Jerry Shi Author(s) Release Date September lOth 2008 Page 1 of98 CONFIDENTIAL TREATMENT REQUESTED BY BARCLAYS LBEX-BARFID 0011765 Global Consolidated Policy on Valuation Adjustments Version Control ............................................................................................................................. 9 4.10.4 Updated Bid-Offer Delta: ABS Credit SpreadDelta................................................................ lO Commodities for YH. Bid offer delta and vega .................................................................................. 10 Updated Muni section ........................................................................................................................... 10 Updated Section 13 ............................................................................................................................... 10 Deleted Section 20 ................................................................................................................................ 10 Added EMG Bid offer and updated London rates for all traded migrated out oflens ....................... 10 Europe Rates update ............................................................................................................................. 10 Europe Rates update continue .............................................................................................................