Thehymnbook of Valentin Triller OA.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hudba Slezských Skladatelů Od 15. Do 20. Století (1. Díl)

Muzyka kompozytorów śląskich XV-XX wieku (cz. 1) The music of Silesian composers from the 15th to 20th centuries (part I) Die Musik der schlesischen Komponisten vom 15. bis zum 20. Jh (I. Teil) Hudba slezských skladatelù od 15. do 20. století (1. díl) 2 Redaguje zespół / editorial staff: Artur Bielecki (konsultant muzyczny / musical consultant) Przemysław Jastrząb (redaktor graficzny / graphics editor) Piotr Karpeta (konsultant muzyczny / musical consultant) Edyta Kotyńska (redaktor naczelna / editor-in-chief) Poszczególne opisy opracowali / descriptions written by: Alicja Borys (AB) Beata Krzywicka (BK) Małgorzata Turowska (MT) Przekłady na języki obce / translations: Anna Leniart Zuzana Petrášková Dennis Shilts Jana Vozková Korekta: kolektyw autorski / Proof-reading: staff of authors Kopie obiektów wykonali / copies of objects: Pracownia Reprograficzna Biblioteki Uniwersyteckiej we Wrocławiu (Tomasz Kalota, Jerzy Katarzyński, Alicja Liwczycka, Marcin Szala) Wszystkie nagrane utwory wykonuje chór kameralny Cantores Minores Wratislavienses / All recordings of works performed by the Cantores Minores Wratislavienses chamber choir www.cantores.art.pl Skład i druk: Drukarnia i oficyna wydawnicza FORUM nakład 1000 egz. ISBN 83-89988-00-3 (całość) ISBN 83-89988-02-X (vol. 2) © Wrocławscy Kameraliści & Biblioteka Uniwersytecka we Wrocławiu, Wrocław 2004 Wrocławscy Kameraliści Cantores Minores Wratislavienses PL 50-156 Wrocław, ul. Bernardyńska 5, tel./fax + 48 71 3443841, www.cantores.art.pl Biblioteka Uniwersytecka we Wrocławiu PL 50-076 Wrocław, ul. K. Szajnochy 10, tel. + 48 71 3463120, fax +48 71 3463166, www.bu.uni.wroc.pl Wprowadzenie Niniejszy katalog jest rezultatem współpracy bibliotekarzy i muzyków z kilku europejskich ośrodków naukowych oraz jednym z elementów projektu „Bibliotheca Sonans“ dofinansowywanego przez Unię Europejską w ramach programu Kultura 2000. -

JOHANN SEBASTIAN BACH Orgelbü�Chlein

JOHANN SEBASTIAN BACH Orgelbüchlein JOAN LIPPINCOTT , ORGAN JOHANN SEBASTIAN BACH Orgelbüchlein J O A N L I P P I N C O T T , O R G A N 1. | Nun komm, der Heiden Heiland, BWV 599 01:31 23. | Da Jesus an dem Kreuze stund, BWV 621 01:20 2. | Gott, durch deine Güte, 24. | O Mensch, bewein dein Sünde gross, BWV 622 05:28 or Gottes Sohn ist kommen, BWV 600 01:13 25. | Wir danken dir, Herr Jesu Christ, BWV 623 01:01 3. | Herr Christ, der ein’ge Gottessohn, 26. | Hilf, Gott, dass mir’s gelinge, BWV 624 01:22 or Herr Gott, nun sei gepreist, BWV 601 01:42 27. | Christ lag in Todesbanden, BWV 625 01:32 4. | Lob sei dem allmächtigen Gott, BWV 602 00:55 28. | Jesus Christus, unser Heiland, BWV 626 00:54 5. | Puer natus in Bethlehem, BWV 603 00:59 29. | Christ ist erstanden, BWV 627 04:21 6. | Gelobet seist du, Jesu Christ, BWV 604 01:28 30. | Erstanden ist der heil'ge Christ, BWV 628 00:51 7. | Der Tag, der ist so freudenreich, BWV 605 02:01 31. | Erschienen ist der herrliche Tag, BWV 629 01:04 8. | Vom Himmel hoch, da komm ich her, BWV 606 00:46 32. | Heut triumphieret Gottes Sohn, BWV 630 01:27 9. | Vom Himmel kam der Engel Schar, BWV 607 01:23 33. | Komm, Gott Schöpfer, Heiliger Geist, BWV 631 00:59 10. | In dulci jubilo, BWV 608 01:31 34. | Herr Jesu Christ, dich zu uns wend, BWV 632 01:31 11. -

![Fasolis-D-V06c[Brilliant-2CD-Booklet].Pdf](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/6826/fasolis-d-v06c-brilliant-2cd-booklet-pdf-86826.webp)

Fasolis-D-V06c[Brilliant-2CD-Booklet].Pdf

94639 bach_BL2 v8_BRILLIANT 04/02/2013 10:10 Page 2 Johann Sebastian Bach 1685 –1750 Passion Chorales 39 –40 O Lamm Gottes, unschuldig BWV618 3’54 1’24 Orgelbüchlein BWV 599 –644 41 –42 Christe, du Lamm Gottes BWV619 1’01 1’23 with alternating chorales 43 –44 Christus, der uns selig macht BWV620 2’45 1’22 45 –46 Da Jesus an dem Kreuze stund BWV621 2’03 1’10 Compact Disc 1 67’20 Compact Disc 2 67’14 Part I Organ Chorale Advent Chorales Part II Organ Chorale 1–2 Nun komm, der Heiden Heiland BWV599 2’03 0’46 1–2 O Mensch, bewein dein’ Sünde groß BWV622 6’02 2’27 3–4 Gottes Sohn ist kommen BWV600 1’27 1’10 3–4 Wir danken dir, Herr Jesu Christ BWV623 1’03 0’49 5–6 Herr Christ, der ein’ge Gottes Sohn BWV601 1’38 1’09 5–6 Hilf Gott, daß mir’s gelinge BWV624 1’33 1’01 7–8 Lob sei dem allmächtigen Gott BWV602 0’54 0’47 Easter Chorales Christmas Chorales 7–8 Christ lag in Todesbanden BWV625 1’19 1’25 9–10 Puer natus in Bethlehem BWV603 1’18 0’46 9–10 Jesus Christus, unser Heiland BWV626 1’01 0’49 11 –12 Gelobet seist du, Jesu Christ BWV604 1’12 0’48 11 –12 Christ ist erstanden Verse 1 BWV627 1’18 0’50 13 –14 Der Tag, der ist so freudenreich BWV605 1’57 1’18 13 –14 Christ ist erstanden Verse 2 1’14 0’50 15 –16 Vom Himmel hoch, da komm’ ich her BWV606 0’54 0’47 15 –16 Christ ist erstanden Verse 3 1’41 0’49 17 –18 Vom Himmel kam der Engel Schar BWV607 1’10 0’30 17 –18 Erstanden ist der heil’ge Christ BWV628 0’44 0’26 19 –20 In dulci jubilo BWV608 1’24 0’51 19 –20 Erschienen ist der herrlich Tag BWV629 0’50 0’36 21 –22 Lobt Gott, ihr Christen, allzugleich -

Xvii. Tempo En Fermates Bij De Uitvoering Van Koralen in Bachs Cantates En Passies

XVII. TEMPO EN FERMATES BIJ DE UITVOERING VAN KORALEN IN BACHS CANTATES EN PASSIES In dit hoofdstuk staan het tempo van de koralen en de wijze waarop de fermates werden uitgevoerd centraal. Zoals bekend zijn koralen door de gemeente gezongen gezangen tijdens erediensten. In Bachs tijd stonden de tekst en soms ook de melodie hiervan in de gebruikte gezangboeken. De gezangen waren over het algemeen bij de gemeente bekend. Onder kora- len zullen tevens verstaan worden de – meestal vierstemmig homofoon gezette – gezangen, zoals die in Bachs cantates en passies veel voorkomen: zij hadden immers dezelfde tekst en melodie als de gemeentegezangen. Ook wanneer instrumenten een zelfstandige rol hadden, in de vorm van tussenspelen (bijvoorbeeld in het slotkoraal ‘Jesus bleibet meine Freude‘ BWV 147/10) of extra partijen (‘Weil du vom Tod erstanden bist' BWV 95/7), worden ze hier gerekend tot Bachs koralen. Deze studie richt zich niet primair op koraalmelodieën die – meestal éénstemmig – als cantus firmus gezongen of gespeeld worden tijdens een aria of reci- tatief, maar het ligt voor de hand dat de beschreven conclusies hierbij ook van toepassing zijn. In de eerste paragraaf wordt gekeken naar de ontwikkeling van de gemeentezang in Duits- land, en hoe die op orgel begeleid werd. Vervolgens wordt onderzocht hoe er in traktaten over het tempo van de gemeentezang werd gesproken. Daarna worden de resultaten geëx- trapoleerd naar de hoofdkerken in Leipzig onder Johann Sebastian Bach. Het moge zo zijn dat de koralen als gemeentezang langzaam werden uitgevoerd, maar gold dat ook voor de koralen in Bachs cantates? In deze paragraaf wordt getracht een antwoord te vinden op deze vraag. -

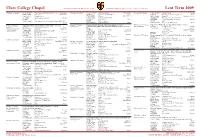

C7054 Clare College Term Card:Layout 1

Clare College Chapel TUESDAYS AND THURSDAYS 6.15 p.m. SUNDAYS 6.00 p.m. (preceded by a recital at 5.30 p.m.) Lent Term 2009. Thursday 15 January VOLUNTARY Puer natus in Bethlehem, BuxWV 217 Buxtehude Thursday 5 February VOLUNTARY Canzona Quinta Frescobaldi Tuesday 24 February VOLUNTARY Sursum Corda Ireland RESPONSES Ayleward PSALM 61 INTROIT Ich bin’s, ich sollte büssen Bach INTROIT Bin ich gleich von dir gewichen Bach CANTICLES Walmisley in d RESPONSES Clucas PSALM 27 RESPONSES Radcliffe PSALM 119: 1–8 ANTHEM Quem vidistis, pastores Dering CANTICLES Causton Fauxbourdon CANTICLES Wood in F (Collegium Regale) HYMN 47 ANTHEM If ye love me Tallis ANTHEM O God, thou hast cast us out Purcell VOLUNTARY Vom Himmel Hoch, da Komm ich her, BWV 606 HYMN 383 (vv. 1, 2, 4) HYMN 404 Bach VOLUNTARY Veni Redemptor Tallis VOLUNTARY Fugue in C, BVW 545/ii Bach Wednesday 25 February Vigil for Ash Wednesday & Imposition of Ashes 10.00 p.m. Sunday 18 January Organ Recital by Simon Thomas Jacobs (Clare) 5.30 p.m. Sunday 8 February Piano Recital by Alexander Bryson (London) 5.30 p.m. Septuagesima Joint Evensong with Universitätschor Innsbruck, Director Georg Ash Wednesday PSALM 51 (Miserere) Allegri Epiphany 2 INTROIT In the bleak midwinter Darke Weiss ANTHEMS O saviour of the world Howells (Week of Prayer for RESPONSES Ayleward PSALM 96 INTROIT Here is the little door Howells O vos omnes Vaughan Williams Christian Unity) CANTICLES Plainsong (Tonus Peregrinus/IIi) RESPONSES Smith PSALM 5 Save me, O God Lavino ANTHEM Magnificat II Swayne CANTICLES Stanford in -

Gesungene Aufklärung

Gesungene Aufklärung Untersuchungen zu nordwestdeutschen Gesangbuchreformen im späten 18. Jahrhundert Von der Carl von Ossietzky Universität Oldenburg – Fachbereich IV Human- und Gesellschaftswissenschaften – zur Erlangung des Grades einer Doktorin der Philosophie (Dr. phil.) genehmigte Dissertation von Barbara Stroeve geboren am 4. Oktober 1971 in Walsrode Referent: Prof. Dr. Ernst Hinrichs Korreferent: Prof. Dr. Peter Schleuning Tag der Disputation: 15.12.2005 Vorwort Der Anstoß zu diesem Thema ging von meiner Arbeit zum Ersten Staatsexamen aus, in der ich mich mit dem Oldenburgischen Gesangbuch während der Epoche der Auf- klärung beschäftigt habe. Professor Dr. Ernst Hinrichs hat mich ermuntert, meinen Forschungsansatz in einer Dissertation zu vertiefen. Mit großer Aufmerksamkeit und Sachkenntnis sowie konstruktiv-kritischen Anregungen betreute Ernst Hinrichs meine Promotion. Ihm gilt mein besonderer Dank. Ich danke Prof. Dr. Peter Schleuning für die Bereitschaft, mein Vorhaben zu un- terstützen und deren musiktheoretische und musikhistorische Anteile mit großer Sorgfalt zu prüfen. Mein herzlicher Dank gilt Prof. Dr. Hermann Kurzke, der meine Arbeit geduldig und mit steter Bereitschaft zum Gespräch gefördert hat. Manche Hilfe erfuhr ich durch Dr. Peter Albrecht, in Form von wertvollen Hinweisen und kritischen Denkanstößen. Während der Beschäftigung mit den Gesangbüchern der Aufklärung waren zahlreiche Gespräche mit den Stipendiaten des Graduiertenkollegs „Geistliches Lied und Kirchenlied interdisziplinär“ unschätzbar wichtig. Stellvertretend für einen inten- siven, inhaltlichen Austausch seien Dr. Andrea Neuhaus und Dr. Konstanze Grutschnig-Kieser genannt. Dem Evangelischen Studienwerk Villigst und der Deutschen Forschungsge- meinschaft danke ich für ihre finanzielle Unterstützung und Förderung während des Entstehungszeitraums dieser Arbeit. Ich widme diese Arbeit meinen Eltern, die dieses Vorhaben über Jahre bereit- willig unterstützt haben. -

Hymnody of Eastern Pennsylvania German Mennonite Communities: Notenbüchlein (Manuscript Songbooks) from 1780 to 1835

HYMNODY OF EASTERN PENNSYLVANIA GERMAN MENNONITE COMMUNITIES: NOTENBÜCHLEIN (MANUSCRIPT SONGBOOKS) FROM 1780 TO 1835 by Suzanne E. Gross Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Maryland in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 1994 Advisory Committee: Professor Howard Serwer, Chairman/Advisor Professor Carol Robertson Professor Richard Wexler Professor Laura Youens Professor Hasia Diner ABSTRACT Title of Dissertation: HYMNODY OF EASTERN PENNSYLVANIA GERMAN MENNONITE COMMUNITIES: NOTENBÜCHLEIN (MANUSCRIPT SONGBOOKS) FROM 1780 TO 1835 Suzanne E. Gross, Doctor of Philosophy, 1994 Dissertation directed by: Dr. Howard Serwer, Professor of Music, Musicology Department, University of Maryland, College Park, Maryland As part of an effort to maintain their German culture, the late eighteenth-century Mennonites of Eastern Pennsylvania instituted hymn-singing instruction in the elementary community schoolhouse curriculum. Beginning in 1780 (or perhaps earlier), much of the hymn-tune repertoire, previously an oral tradition, was recorded in musical notation in manuscript songbooks (Notenbüchlein) compiled by local schoolmasters in Mennonite communities north of Philadelphia. The practice of giving manuscript songbooks to diligent singing students continued until 1835 or later. These manuscript songbooks are the only extant clue to the hymn repertoire and performance practice of these Mennonite communities at the turn of the nineteenth century. By identifying the tunes that recur most frequently, one can determine the core repertoire of the Franconia Mennonites at this time, a repertoire that, on balance, is strongly pietistic in nature. Musically, the Notenbüchlein document the shift that occured when these Mennonite communities incorporated written transmission into their oral tradition. -

ISBN 978-3-7995-0510-9 Musik In

Sonderdruck aus: Michael Fischer, Norbert Haag, Gabriele Haug-Moritz (Hgg.) MUSIK IN NEUZEITLICHEN KONFESSIONS KULTUREN (16. BIS 19. JAHRHUNDERT) Räume – Medien – Funktionen Jan Thorbecke Verlag 005109_sonderdruck.indd5109_sonderdruck.indd 1 227.01.147.01.14 111:471:47 Gedruckt mit Unterstützung der Geisteswissenschaftlichen Fakultät und des Vizerektorats für Forschung und Nachwuchsförderung der Karl-Franzens-Universität Graz Gedruckt mit Unterstützung des Deutschen Volksliedarchivs in Freiburg Gedruckt mit Unterstützung des Evangelischen Oberkirchenrats Stuttgart sowie des Vereins für württembergische Kirchengeschichte. Für die Schwabenverlag AG ist Nachhaltigkeit ein wichtiger Maßstab ihres Handelns. Wir achten daher auf den Einsatz umweltschonender Ressourcen und Materialien. Dieses Buch wurde auf FSC®-zertifiziertem Papier gedruckt. FSC (Forest Stewardship Council®) ist eine nicht staatliche, gemeinnützige Organisation, die sich für eine ökologische und sozial verantwortliche Nutzung der Wälder unserer Erde einsetzt. Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen National- bibliografie; detaillierte bibliografische Daten sind im Internet über http://dnb.d-nb.de abrufbar. Alle Rechte vorbehalten © 2014 Jan Thorbecke Verlag der Schwabenverlag AG, Ostfildern www.thorbecke.de Umschlaggestaltung: Finken & Bumiller, Stuttgart Umschlagabbildung: Stahlstich Eine feste Burg ist unser Gott von H. Gugeler (Gesangbuch für die evangelische Kirche in Württemberg, -

Musicalische Exequien

BERNVOCAL Leitung: Fritz Krämer bernvocal.ch Heinrich Schütz (1 585–1 672) Musicalische Exequien PROGRAMM Fr 1 3.1 1 .201 5 20.00 Bern, Nydeggkirche Sa 1 4.1 1 .201 5 20.00 Biel, Stadtkirche So 1 5.1 1 .201 5 1 7.00 Fribourg, Couvent des Capucins PRO G RAM M Herr, nun lässest du deinen Diener in Frieden fahren SWV 432 LUKAS 2, 29–32 Das ist je gewisslich wahr SWV 277 1 . TIMOTHEUS 1 , 1 5 Unser Wandel ist im Himmel SWV 390 PHILIPPER 3, 20–21 Herzlich lieb hab ich dich, o Herr SWV 387 [MARTIN SCHALLING] Gutes und Barmherzigkeit werden mir folgen SWV 95 PSALM 23, 6 Michael Praetorius (1 571 –1 621 ): Ballet (aus Terpsichore) Musicalische Exequien I. Konzert in Form einer deutschen Begräbnis-Missa SWV 279 Nacket bin ich von Mutterleibe kommen HIOB 1 , 21 Nacket werde ich wiederum dahin fahren HIOB 1 , 21 Herr Gott, Vater im Himmel [KYRIE I] Christus ist mein Leben PHILIPPER 1 , 21 ; JOHANNES 1 , 29 Jesu Christe, Gottes Sohn [CHRISTE] Leben wir, so leben wir dem Herren RÖMER 1 4, 8 Herr Gott, heiliger Geist [KYRIE II] Also hat Gott die Welt geliebt JOHANNES 3, 1 6 Auf dass alle, die an ihn gläuben JOHANNES 3, 1 6 Er sprach zu seinem lieben Sohn [MARTIN LUTHER 1 523] Das Blut Jesu Christi 1 . JOHANNES 1 , 7 Durch ihn ist uns vergeben [LUDWIG HELMBOLD 1 575] Unser Wandel ist im Himmel PHILIPPER 3, 20–21 Es ist allhier ein Jammertal [JOHANN LEON 1 592–98] Wenn eure Sünde gleich blutrot wäre JESAJA 1 , 1 8 Sein Wort, sein Tauf, sein Nachtmahl [LUDWIG HEMBOLD 1 575] Gehe hin, mein Volk JESAJA 26, 20 Der Gerechten Seelen sind in Gottes Hand WEISHEIT 3, 1 –3 Herr, wenn ich nur dich habe PSALM 73, 25 Wenn mir gleich Leib und Seele verschmacht PSALM 73, 26 Er ist das Heil und selig Licht [MARTIN LUTHER 1 524] Unser Leben währet siebenzig Jahr PSALM 90, 1 0 Ach, wie elend [JOHANNES GIGAS 1 566] Ich weiss, dass mein Erlöser lebt HIOB 1 9, 25–26 Weil du vom Tod erstanden bist [NIKOLAUS HERMAN 1 560] Herr, ich lasse dich nicht 1 . -

Der Komponist Als Prediger: Die Deutsche Evangelisch-Lutherische Motette Als Zeugnis Von Verkündigung Und Auslegung Vom Reformationszeitalter Bis in Die Gegenwart

DER KOMPONIST ALS PREDIGER: DIE DEUTSCHE EVANGELISCH-LUTHERISCHE MOTETTE ALS ZEUGNIS VON VERKÜNDIGUNG UND AUSLEGUNG VOM REFORMATIONSZEITALTER BIS IN DIE GEGENWART Dissertation zur Erlangung des Doktorgrades vorgelegt beim Fachbereich 2 Kommunikation/Ästhetik Fach Musik/Auditive Kommunikation Carl von Ossietzky Universität Oldenburg von Jan Henning Müller Salbeistraße 22 26129 Oldenburg Oldenburg (Oldb) Juli 2002 Tag der Einreichung: 31.Juli 2002 Tag der Disputation: 29.Januar 2003 Gutachter: Prof. Dr. Peter Schleuning, Prof. Dr. Wolfgang E. Müller Inhaltsverzeichnis 1 EINLEITUNG 4 1.1 Thematische Einführung und Abgrenzung 4 1.2 Zur Darstellung 5 1.3 Gattungsspezifische Annäherung in vier Schritten 7 1.3.1 „Gattung“ als Vorstellung, Begriff und Kategorie 7 1.3.2 Musikalische Gattungen 10 1.3.3 Die Motette als musikalische Gattung 13 1.3.4 Zur Spezifität der evangelisch -lutherischen Motette 17 1.4 Konsequenzen für die Analyse und Motettenkorpus 20 1.4.1 Zur Analyse 20 1.4.2 Motettenkorpus 24 2 VORAUSSETZUNGEN IM MITTELALTER UND IM HUMANISMUS 26 2.1 Rhetorik, Homiletik und Predigt 26 2.2 Zum vorreformatorischen Musikbegriff 31 2.3 Gattungsgeschichtlicher Abriss: die Motette bis etwa 1500 34 3 „SINGEN UND SAGEN“: DIE GENESE DER GATTUNG 41 3.1 Aussermusikalische Faktoren 41 3.1.1 Theologische Voraussetzungen 41 3.1.2 Zum Musikbegriff der Reformatoren (Luther, Walter, Melanchthon) 55 3.1.3 Erste deutschsprachige Predigtmotetten 67 3.2 Innermusikalische Faktoren 82 3.2.1 Beispielfundus 82 3.2.2 Textdisposition 84 3.2.3 Modale Affektenlehre 91 3.2.4 Klausellehre und Klauselhierarchie 94 3.2.5 Musikalische Deklamation 110 3.2.6 Musikalisch-rhetorische Figuren 117 3.2.7 Analyseschema 127 4 DIE EV.-LUTH. -

Reception of Josquin's Missa Pange

THE BODY OF CHRIST DIVIDED: RECEPTION OF JOSQUIN’S MISSA PANGE LINGUA IN REFORMATION GERMANY by ALANNA VICTORIA ROPCHOCK Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Dissertation Advisor: Dr. David J. Rothenberg Department of Music CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY May, 2015 CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES We hereby approve the thesis/dissertation of Alanna Ropchock candidate for the Doctor of Philosophy degree*. Committee Chair: Dr. David J. Rothenberg Committee Member: Dr. L. Peter Bennett Committee Member: Dr. Susan McClary Committee Member: Dr. Catherine Scallen Date of Defense: March 6, 2015 *We also certify that written approval has been obtained for any proprietary material contained therein. TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Tables ........................................................................................................... i List of Figures .......................................................................................................... ii Primary Sources and Library Sigla ........................................................................... iii Other Abbreviations .................................................................................................. iv Acknowledgements ................................................................................................... v Abstract ..................................................................................................................... vii Introduction: A Catholic -

Universiv Microtlms International 300 N

INFORMATION TO USERS This reproduction was made from a copy o f a document sent to us for microfilming. While the most advanced technology has been used to photograph and reproduce this document, the quality of the reproduction is heavily dependent upon the quality of the material submitted. The following explanation of techniques is provided to help clarify markings or notations which may appear on this reproduction. 1.The sign or “target” for pages apparently lacking from the document photographed is “ Missing Page(s)” . I f it was possible to obtain the missing page(s) or section, they are spliced into the film along with adjacent pages. This may have necessitated cutting through an image and duplicating adjacent pages to assure complete continuity. 2. When an image on the film is obliterated with a round black mark, it is an indication of either blurred copy because of movement during exposure, duplicate copy, or copyrighted materials that should not have been filmed. For blurred pages, a good image o f the page can be found in the adjacent frame. If copyrighted materials were deleted, a target note w ill appear listing the pages in the adjacent frame. 3. When a map, drawing or chart, etc., is part o f the material being photographed, a definite method of “sectioning” the material has been followed. It is customary to begin film ing at the upper left hand comer o f a large sheet and to continue from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. I f necessary, sectioning is continued again-beginning below the first row and continuing on until complete.